Jan Vaněk was arguably the most obvious of all the prototypes of characters in The Good Soldier Švejk.

The Who's who page on Jaroslav Hašek presents a gallery of persons from real life who to a varying degree are associated with The Good Soldier Švejk and his creator. Several of the characters in the novel are known to be based on real-life people, mostly officers from Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. Some of Hašek's literary figures carry the full names of their model, some are only thinly disguised and some names diverge from that of their "model", but they can be pinpointed by analyzing the circumstances in which they appear.

A handful of "prototypes" are easily recognisable like Rudolf Lukas and Jan Vaněk, others like Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj and Emanuél Michálek are less obvious inspirations. One would also assume that most of these characters borrow traits from more than one person, one such example is Švejk himself.

A far larger number of assumed prototypes are connected to their literary counterparts by little more than the name. Josef Švejk is here the prime example, but Jan Eybl also fits in this category. The list of prototypes only contains those who inspired characters that directly take part in the plot.

Researchers, the so-called Haškologists, are also included on this page but this list is per 15 June 2022 restricted to Radko Pytlík and two important but relatively unknown contributors to our knowledge about Hašek and Švejk. In due course entries on other experts like Václav Menger and Zdena Ančík will be added.

| Hašek, Jaroslav Matěj František | ||||||

| *30.4.1883 Praha - †3.1.1923 Lipnice nad Sázavou | |||||||

| |||||||

Hašek embedded innumerable autobiographical elements and episodes from his own unusual life experience into his famous The Good Soldier Švejk. He no doubt served as direct inspiration not only for Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek, but even more so for the book's main character, the soldier Švejk himself. The most relevant period with regards to The Good Soldier Švejk is of course the author's time in k.u.k. Heer in 1915, although sequences that draw from other periods of the writer's life appear throughout the novel.

Please note that the scope of this page is limited to periods and episodes in Hašek's life that had an obvious and direct impact on The Good Soldier Švejk, first and foremost his time in k.u.k. Heer.

Jaroslav Hašek mirrored in Josef Švejk

Żdżary, 18 August 1915. Hašek decorated.

© ÖStA

The author attaches unmistakable personal characteristics directly to his literary hero. In the first few lines of The Good Soldier Švejk he exposed his own rheumatism to world literature "by proxy", and we can safely assume that Švejk’s verbal skills, quick wits, charm, calm, and the all-important ability to talk/wriggle himself out of difficult situations were gifts he inherited from his creator. This very strategy for survival was something that both Švejk and Hašek shared. Both were also outgoing and sociable persons, liked to tell stories and to entertain.

Even more striking are the similarities between Hašek’s and Švejk’s military careers. They both lived in Prague, but served in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 (IR. 91) due to their South Bohemian ancestry. They were mostly present in the same places and in the same historical circumstances during their time in k.u.k. Heer. Many of Švejk’s superiors and peers are inspired by Hašek’s own milieu in IR. 91, albeit with their qualities and identities modified, caricatured and partly disguised. Švejk was company messenger in his 11. Marschkompanie which corresponds exactly with Hašek’s role in 11. Kompanie. In addition, both were assigned the responsibility of finding accommodation for their military units.

An obvious pre-war connection between Švejk and the author is the occupation. From November 1910 Hašek ran a short-lived dog-trading enterprise but was accused of selling dogs with fake pedigrees, dogs who had been stolen by his assistant. Both had also been apprentice chemists. Švejk's stay at blázinec (lunatic asylum) has clear traces of autobiography, likewise his stays at c.k. policejní ředitelství (Police HQ), c.k. zemský co trestní soud (Country criminal court) and Policejní komisařství Salmova ulice (Salmovská ulice). Of course Hašek and his hero both shared the liking of life in the pubs, and many of the establishments mentioned in the novel were favourites of the author (U Fleků, Bendlovka, Montmartre, U Brejšky - to name a few). Their indifference to (or lack of luck with) ladies seems to be another common trait. They also liked to sing army songs but were by all accounts very poor singers.

One-year volunteer Marek

Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek seems to be even more consistently modelled on the satirist, portraying an intellectual side of his personality that he never assigns to Švejk. Marek borrows a number of biographical details from Hašek.

His occupation as editor of Svět zvířat reflects Hašek's position at the magazine in 1909 and 1910, although many of the details that Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek provides is mystification, namely his invented animals. Švejk and Marek, Hašek's two alter egos enjoying themselves in Regimentsarrest in Budějovice

Marek’s experiences in Budějovice also have traces of Hašek's autobiography: his status as one-year volunteer, turning up at the exercise ground in civilian clothes, being dismissed from the School for one-year volunteers, his arrest by artillery patrols and hospitalisation. The affair with the Krankenbuch may also be inspired by some incidence that actually took place. Hašek was allegedly, like his literary alter-ego Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek, transported from Budějovice to Királyhida in the prisoner's carriage. On a general note it is evident that Marek is the mouth-piece for Hašek's own political views. In this respect he is the very opposite of Švejk who conceals his opinions whenever it serves him.

Although Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek and Švejk are the figures that most obviously bear traces of the author, it is tempting to suggest that Hašek contributed a few of his less admirable qualities to at least two more of his literary creations: Offiziersdiener Baloun (gluttony), and Feldkurat Katz (alcoholism and shirking financial obligations, ref. not paying the moneylender in [I.13]).

Anecdotes

Many of the numerous monologues show traces of Hašek’s own experiences. An example of this is the introduction of his own grandfather Jareš at several points in the novel, starting in the first chapter. Similar examples abound, like the two anecdotes about Rittmeister Rotter, and the anecdote about "nějakej" (some) Mestek.

Before the draft

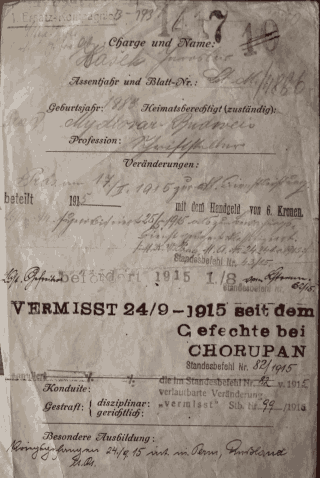

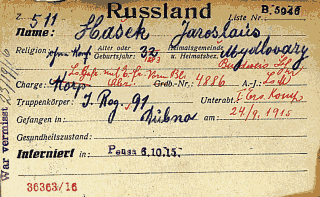

Jaroslav Hašek's Vormerkblatt Nr. 4886

© VÚA

Jaroslav Hašek was 31 years old in 1914 and had avoided military service so far. The reasons for this are unknown and no records of his early encounters with the armed forces have been found. He must either have been declared unfit for armed service (Waffenunfähig) or dismissed after starting it (Superarbitriert). According to Emil Artur Longen, Hašek was disappointed because he hadn't been admitted to the army and was proud when he was finally deemed Tauglich after the outbreak of war. This seems likely as his military medical records state that he was "Assentiert" (drafted) in 1914. As a result of this he was assigned to Landsturm (Home Guard or militia), a reserve force that was only called up in times of danger. In the autumn of 1914, it was decided to reassess this large reserve of manpower to offset the losses at the front. From 13 to 15 December 1914 the Landsturm medical examination for Hašek's age group and geographical affinity took place at Střelecký ostrov. Those who passed were to report for duty on 15 February 1915. The parallel to Švejk is obvious although the chronological details differ (as is the case throughout the novel). It is also striking that the author mentions that Doctor Bautze had been acting for 10 weeks in his role as the head doctor at the medical board, and we know that Landsturm medical examinations started on Střelecký ostrov on 1 October 1914. This fits very well with mid December. It should also be noted that Bautze declared 10,999 of 11,000 recruits fit for service. In fact only about 60 per cent of the early recruits were deemed Tauglich, and by the end of the year when Hašek's age group was called up, the rate of acceptance had dropped towards 30 per cent.

In Budějovice

Jaroslav Hašek's time in IR. 91 deserves particular attention as it is during this period the novel comes closest to an autobiography and more than half the plot is set in k.u.k. Heer. According to army records Hašek was Präsentiert (reported at) 1. Ersatzkompanie in Ersatzbataillon IR. 91 on 17 February 1915. Here in Budějovice he enlisted at the school for reserve officers where he met some of the people he would later caricature in his writing: Hauptmann Josef Adamička (head of the school), Oberleutnant Čeněk Sagner, and Fähnrich Hans Bigler. He may also have met Major Franz Wenzel and staff sergeant Jan Vaněk, but this has not been possible to verify. Senior lieutenant Rudolf Lukas was at the front in the Východní Beskydy until 13 march, then on sick-leave, so they would only have met later, presumably in early June in Királyhida. In Budějovice Hašek also met fellow soldiers who forty or more years later would provide researchers with vital information that however often was blurred due to the distance in time: Jaroslav Kejla, Bohumil Vlček, Franta Hofer, Bohumil Šindelár, František Skřivánek to mention a few. ,13.3.1915

His stay at the school proved unsuccessful. Due to his poor physical condition he found the exercises and drill taxing and according to his own writing (confirmed by Kejla and Hofer) he was expelled from the school. The exact reason for the dismissal is not clear, although he himself gives a few colourful accounts both through Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek (in Švejk) and in the short stories Gott Strafe England and In strategic difficulties. Kejla and Hofer offer a more mundane view: Hašek was dismissed for behaviour that was incompatible with that expected of a k.u.k. officer. Most likely it was drunkenness and public order violations (he had been repeatedly arrested for such offences in Prague). Still the eloquent and rebellious author may well have upset his superiors sufficiently to get himself disciplined, but hardly expelled. There is no mention of Hašek in lists of graduates from Reserveoffizier-Schule Budweis so there is no doubt that he had left the school.

Generally he seems to have taken little part in military life, some of it doubtlessly because of illness but surely also because he was locked up from time to time (according to himself as long as 30 days). Suffering from rheumatism and heart-trouble, he was first hospitalised on 6 March near the railway station in the k.u.k. Reserve-Spital in Radeckého třída. A note on his hospitalisation appeared in Jihočeské listy on 13 March 1915. Then he was sent to a recuperation unit in Linecké předměstí. From here he seems to have been able to make a few excursions. The longest was for four days and he got as far as Protivín and Netolice, some claim that he even appeared in Radomyšl. He is also reported to have been to Zliv and České Vrbné. During his stay in Budějovice he wrote a few short stories and even had the collection "My business with dogs" published at this time. Hašek in k.u.k. Reservespital, Budweis

In the 1950s several witnesses recorded their reminiscences from Hašek's time in Budějovice, but most of them suffer in accuracy due to the distance in time. One of them was František Skřivánek who published the details in Stráž míru, 8 September 1954 (a similar story had appeared in Jihočeské listy as early as 1923). During his time in the city the author visited an impressive range of pubs (no surprise here), but only a few of them seem to have found their way into the novel. Amongst the cluster of witnesses was young Bohumil Mičan whose family owned the restaurant U Mičanů that Hašek frequented. He also slept over at their place and got to know the family well.

Another witness was fellow one-year volunteer Franta Hofer. He gives an amusing account of Hašek's first weeks at the reserve-officer school and adds that many officers liked the author (notably Josef Adamička) and invited him to the canteen to entertain the officer's. This may have inspired the passages in the novel that take place in the local hotel and in the officer's dining rooms. Hofer's and Mičan's stories seem never to have been published, but they are available in LA PNP, fond Zdena Ančík and links are provided below. Another source of information is František Langer who wrote that the poet Peter Křička had stopped over in Budějovice on his way home from the front and met Hašek. He was at the time working in the kitchen peeling potatoes, a story that aligns well with Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek from the novel and also the author's own In strategical difficulties.

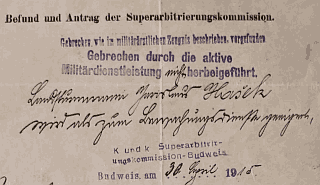

Rheumatism, heart-trouble and superarbitration

The verdict of the superarbitration-commission.

© VÚA

In May 2015 Hašek's military record was investigated at VÚA and the picture of his illness and superarbitration becomes clearer. Already on 6 March 1915 he was admitted to hospital and seem to have stayed there at least until 8 April. He was suffering from rheumatism in the joints, as well as a heart condition, and an application for having him dismissed from the army for health reasons was lodged that day.

On 30 April the superarbitration commission gave its verdict. The soldier was not relieved from army duties entirely: he was deemed capable of salvage, guard and other lighter tasks. It was also concluded that none of his health problems were caused by his military service. The decision was rubber-stamped by k.u.k. Militärkommando Prag on 25 May.

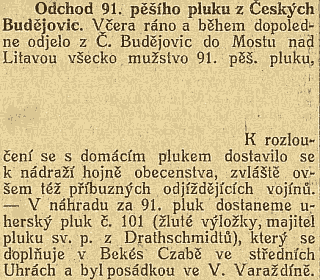

The 91st regiment transferred

,2.6.1915

,11.6.1915

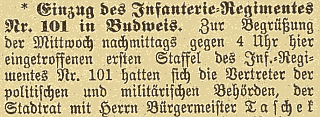

As reflected in the The Good Soldier Švejk Ersatzbataillon IR. 91 was transferred to Királyhida, a town on the border between the two constituent parts of the Dual Monarchy. The reason for the transfer was political; regiments from the various parts of the empire were moved to “foreign” parts because the authorities assumed (not without reason) that too close contact between the k.u.k. “Kanonen-futter” and the civilian population could harm their will to die for the emperor and could also be infected by anti-war sentiments that were taking root in the population as it became clear that the war would not be over soon. Czech reserve battalions were often swapped with Hungarians (or others), and in Budějovice the Hungarian Infanterieregiment Nr. 101 replaced them.

Hašek was surely part of this transfer and describes it in his novel. According to Jan Vaněk he arrived in Királyhida under arrest, just like Švejk did. In literature about Hašek there has been contradictory information regarding the actual date of the transfer. Radko Pytlík gives various dates is early May whereas Jaroslav Kejla claims it took place on the 20th. František Skřivánek remembered that Hašek wrote him a few lines of goodbye, dated 5 May. The actual transfer took however place much later, on 1 June 1915. This is confirmed by Jihočeské listy, Budweiser Zeitung, and Deutsche Böhmerwaldzeitung. The departure scenes by the station are described by the newspapers and correspond to the description in the novel, that a sizable crowd was gathered etc. In the first two newspapers many lines have been removed by the censors. Perhaps these contained the Czech nationalist sentiments that the author describes?

The departure took place before noon, in two stages. Their replacement, Infanterieregiment Nr. 101 from Hungary, arrived during the evening of the 9th and occupied the now vacant Mariánská kasárna.

Bruck/Királyhida

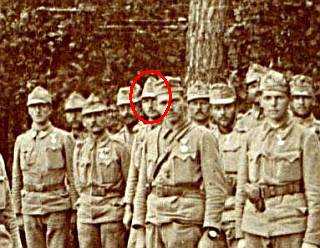

Hašek in IR. 91, probably in Żdżary in August. To the left of him is František Strašlipka (with the cigarette).

As we already know Jaroslav Hašek had on 25 May been partly superarbitrated on health grounds and assigned lighter duties (capable of Rettungsdienst, i.e. rescue duties). After arriving in Királyhida this put him in contact with Jan Vaněk, a staff sergeant who was responsible for accounting and logistics. Vaněk was subsequently to find his way into world literature through this encounter. He was arguably the most obvious of all the “prototypes” found in The Good Soldier Švejk. Hašek helped him with the office duties, and also got to know the cook Perníček, perhaps an inspiration for cook Jurajda. Vaněk was to provide valuable testimonies about Hašek's time in the k.u.k. Heer, as retold by Jan Morávek in 1924 in Večerní České slovo. The series from 1924 is by far the most detailed we have on Hašek's period in the Austro-Hungarian army, and should be considered the very first contribution to “Švejkology”. Morávek also personally met the author in Királyhida.

XII./91 Marschbataillon

Hašek in IR. 91. According to Jan Morávek this photo was taken at the beginning of September 1915 with Hašek already promoted to Gefreiter.

XII. Marschbataillon of IR. 91 was formed around 1 June 1915, and the soldiers continued training and preparation for front duty. The commander of the battalion was Franz Wenzel, a major who served as inspiration for Major Wenzl in the novel.

Each battalion consisted of four companies, and Hašek was assigned to the 4th (deduced from the Qualifikationsbeschreibung of Hans Bigler). Kejla however assigns him to the 3rd company and Vlček to the 2nd! There is however no doubt that Švejk’s 11th march company never existed. This fictional unit is rather a projection of 11. Kompanie in which Jaroslav Hašek was soon to serve.

On 1 June Rudolf Lukas was appointed commander of the 4th march company. With this Oberleutnant Hašek developed a good relationship, a bond that found its way into world literature some six years later. Lukas kept his hand over the author and even urged him to stop drinking. In the march company he also met Hans Bigler again, the prototype of Kadett Biegler, and František Strašlipka, the servant of Lukas. Apart from his position as an officer servant, Strašlipka is also believed to have inspired Švejk’s incessant storytelling and was one of Hašek's closest friends in the regiment.

Departure for the front loomed and on 24 June the men were barred from leaving the camp as they were to depart three days later. Hašek disappeared and was only found after three days, according to one report drunk in a haystack, according to another he was discovered in the same state in a café by the railway station, and according to Jan Morávek (interview printed in Průboj on 3 March 1968) he was found in U zlatého růže (Zur Goldene Rose). Jan Vaněk's diary reveals that the march battalion departed from Bruck station at 8:15 PM on 30 July.

Across the Carpathians

Hašek in IR. 91 (extracted from the picture above)

The journey from Bruck to Sambor is not documented in any known official material, but Jan Vaněk's diary gives a rough idea. It has details on the departure, some places along the route and also mentions three dates. The author himself adds substance through Švejk but even more importantly in his poem “Cestou na bojišti” (On the road to the battle field). The poem was written more or less “on the spot” so it is likely to be more accurate than his later writings. Vaněk described a route that was identical to Švejk’s from Bruck (30 June 1915), Győr, Budapest, Miskolc and Humenné (2 July). Thereafter there is no mention of any places until Sambor.

Jan Vaněk confirms that the train journey terminated in Sambor, a town they approached on 4 July 1915. Hašek in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí even has the soldiers continue beyond Sambor to a station he calls Kamenec (not identified). The novel itself draws a very different picture: it has the march battalion leave the train much earlier, in Sanok. Hašek himself mentions Łupków Pass also in The Good Soldier Švejk in captivity, so we can safely assume that the route described in The Good Soldier Švejk is accurate at least until Zagórz by Sanok. On the way to Sambor the train would have passed more places that are familiar to readers of the novel: Krościenko, Chyrów and Felsztyn.

The only stretch where Hašek's and Švejk's routes diverge is between Sanok and Krościenko. Given the timing- and geographical constraints it can not have taken place as described in the chapter "Marschieren Marsch!" and the battalion would definitely not have been marching with any brigade. The map Jaroslav Hašek u své marškumpanie shows XII. Marschbataillon route to the front (updated with information from the diary of Jan Vaněk, 1 June 2014).

"Einkantonierung" and marching to the front

The orders directing IR. 91 to their Einkantonierungsgebiet east of Sambor.

© ÖStA

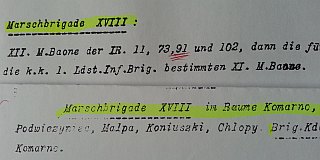

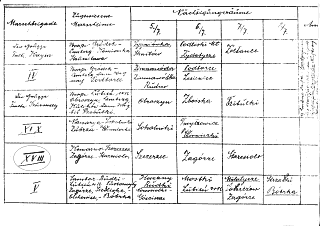

Official 2nd Army orders were the following: the “Einkantonierungsgebiet” was Komarno (ukr. Комарно), east of Sambor, and the daily legs are outlined in detail. Note that this was the planned route and not necessarily the one that was carried out.

- 5 July: Komarno - Szczerzec (ukr. Щирець)

- 6 July: Szczerzec - Zagorsze (ukr. Заґiря)

- 7 July: Zagorsze - Stare Sioło (ukr. Старе Село)

In the “Einkantonierungsgebiet” the 12th march battalions from Infanterieregiment Nr. 11, IR73, IR. 91 and IR102 were to gather and form the 18th March Brigade and continue to the front. Interestingly IR. 91 disappears from the records whereas the march battalions from the other three regiments are reported to have arrived at their destination on 9 July. Jan Vaněk's diary gives us the most reliable information available to date: on 4 July they are still in the transport but approaching Sambor. Then on 5 July they left Sambor for Rudki, on 6 July they marched to Szczerzec. This indicates a delay of one day compared to the 2nd Army orders.

The planned route towards the front. © ÖStA Hašek as Kriegsordonnanz in IR. 91/11th field company © VÚA

Another of Jaroslav Hašek's poems lists towns and villages on a line between Sambor and Łonie (the village by Gołogóry where the XII. Marschbataillon joined the field battalions of IR. 91). This description in the poem corresponds almost perfectly to official orders stored in Kriegsarchiv in Vienna (2nd army files) and Jan Vaněk adds several confirmatory items in his entry from 10 July. The places he mentions are: Wańkowce, Lahodów, and Jaktorów. At the last place he notes on 10 July that they were waiting to join the regiment in the afternoon. The only slight contradiction between the various sources is the actual date of joining the regiment. According to Jan Eybl and Vaněk it was on 10 July, Inft. Reg. 91 Galizien... claims 11 July.

Joining the 11th Field Company

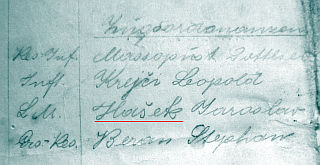

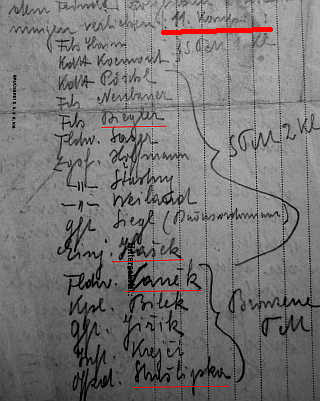

Fähnrich Biegler and Einjährig-Freiwilliger Hašek from the 11th company were awarded silver medals for corageous conduct at Sokal. Feldwebel Vaněk and Offiziers-Diener Strašlipka were given bronze medals.

© VÚA

However patchily Hašek’s journey to the front is documented, his stay at the front from around 10 July to 24 September 1915 is very well covered. Morávek’s above-mentioned series focuses mainly on this period and additionally Inft. Reg. 91 Galizien... covers the regiment's route in great detail, at times almost down to the hour and with accurate geographical information. The diaries of Jan Vaněk and Jan Eybl pin down the events even more accurately.

When the march battalion (appx. 800 men) joined the IR. 91 operative body, Rudolf Lukas took command of the renewed 11. Kompanie, with Hašek as his messenger. Hans Bigler was also assigned to this company as a squad leader (Zugsführer) and Jan Vaněk and František Strašlipka served in this unit. Companies 9 to 12 made up III. Feldbataillon, commanded by Čeněk Sagner who had left for the front around mid June. Franz Wenzel assumed command of the 2nd battalion (companies 5-8).

From now it should be clear that the 11. Kompanie (field compnay) and part of its command structure has been projected directly onto the march units described in the novel. Hašek was named messenger in the 11th field company soon after 11 July 1915, this is a role Švejk gets much earlier in the 11th march company (although Hašek may have been a messenger also in his march company).

After Żółtańce

Although the novel geographically ends at Żółtańce (IR. 91 made a 2 hour 15 minute break here on 16 July), the period after is still interesting even seen from the view of the pure “švejkologist”. Fragments from IR. 91's continuous march still appear in the novel and the most notable of those is Sokal which is dedicated a chapter header as early as Királyhida, in the final chapter of Part Two. The vicious battle that was fought here during the last week of July was no doubt intended to play a prominent part in the unfinished Part Four.

Some real events have been shifted forward in time. The order to build a bridge across the Bug was given on 17 July, i.e. not in Királyhida as the novel states. Brought forward in the same way is the order to march to Sokal. It was only issued on 20 July when the regiment was busy building that very bridge, by Kamionka Strumiłowa. During the march to Sokal the regiment met German troops both in Mosty Wielkie and Sokal (IR. 91 replaced German units there), both these encounters may have inspired the various meetings with German military units and Švejk observing the well-fed Germans at Żółtańce town square (a place IR. 91 never set foot at).

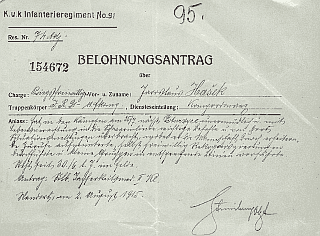

Belohnungsantrag

Application for reward, 2 August 1915.

© ÖStA

Hat in den Kämpfen am 25./7. nächst Poturzyce unermüdlich u. mit Lebensverachtung in die Schwarmlinie [= Schützen- oder Gefechtslinie] wichtige Befehle und von dort Situationsmeldungen überbracht, wobei er die Mannschaft durch Erheitern u. Zurufe aufmunterte, selbst freiwillig Rekognoszierungen [Erkundungen] durchführte und kleine Gruppen in entsprechende Linien vorführte.

Steht seit 30./6. l. J. [laufenden Jahres] im Felde

Antrag: Silb. Tapferkeitsmed. II Kl.

Standort, am 2. August 1915

Transkription dank Doris & Gert Kerschbaumer

Jaroslav Hašek was indeed decorated with the Silver Medal for bravery (II. Class) in the aftermath of the battle by Sokal. The application for his decoration was written on 2 August 1915, signed by Steinsberg (for the regiment). Oddly enough his rank is noted as "Kriegsfreiwilliger" (war volunteer). If this is correct it means that he joined the army voluntarily.

The justification for the award was the bravery he displayed on 25 July 1915, the first day of an Austrian attack whose aim was to recapture the strategically important Góra Sokal, 254 metres. Without regard for his own life he had carried important messages to and from the trenches, encouraged his comrades with shouts, had voluntarily undertaken reconnaissance, and led smaller groups into position.

On 4 August 1915 the application was approved by Mossig for the brigade and Schenk for the division. The medals were handed out on 18 August. Soldiers from Hašek's 3rd battalion were decorated by Rudolf Kießwetter . That day Hans Bigler, Jan Vaněk, and František Strašlipka also received their awards.

The official rubber stamp was given by the central authorities as late as 20 November, at a time when the author was already in Russian captivity.

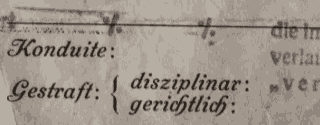

More loyal than made out to be?

Jaroslav Hašek had no disciplinary record in k.u.k. Heer

© VÚA

Much has been made of Jaroslav Hašek's alleged disloyalty to k.u.k. Heer, an impression he himself for obvious reasons was eager to promote from 1916 onwards. He had also before the war talked about his intention of defecting. For years it was therefore an established "fact" that he actively crossed over to the Russians at Chorupan 24 September 1915, that he tried to desert on several occasions before that, that he was even given a three year sentence for attempted desertion. None of these claims have been verified, and there is no sign of any punishment on his military record. On the other hand it is documented that he was awarded a silver medal for bravery, taking risks that he didn't have to take, that he may even have signed up as a Kriegsfreiwilliger, in fact volunteered for his emperor. Nor was he forced to enlist at the reserve officer's school in Budějovice. His superior in k.u.k. Heer, Rudolf Lukas, told Jan Morávek that Hašek was a good soldier, that his main problem was alcohol, and did not mention any political stance. Bohumil Vlček quoted Hašek from Sokal: "this war we must win at all costs". On the other hand he volunteered for reconnaissance patrols at Sokal and it is known that Czech soldiers used this method to get over to the other side. That he actually intended this would however be pure speculation.

There is no doubt that he, like Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek, was locked up in the garrison prison from time to time, but again it was likely to be public order offences rather than politics. The only instance we know of where he was disciplined for a political outburst was actually in České legie in 1917 (after his infamous article The Czech Pickwick Club). It is also tempting to ask that if he was so convinced in his anti-Austrian views, why did it take him eight months to land on the "other side"? He probably could have done what the main target of his scorn in the "Czech Pickwick Klub", Bohdan Pavlů, did in late 1914: join the Czech volunteers on the spot of capture or shortly thereafter. Ernst Kollmann who was in the same prisoner transport as Hašek noted that Družina recruited already in the transit camp at Darnytsa so he surely would have had a chance to join there.

Hašek's time in Russia reflected in Švejk

Kriegsgefangenenkartei

© ÖStA

Jaroslav Hašek and his time in Russia (1915-1920) is comprehensively covered under the headline České legie, and there is little from this period that is directly reflected in The Good Soldier Švejk. One exception is the author's description of officer's servant where he mentions the Legions directly and also describes a "pucflek's" journey into captivity carrying his master's luggage. They route described is at least partly identical to that of the author (see Dubno, Darnytsa).

,17.7.1917 Hochverräterische Umtriebe ...

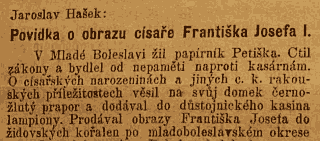

A more co-incidental connection is the story of a tomcat soiling a picture of the emperor, a clear parallel to the scene from U kalicha where the flies were equally impertinent to his majesty. The story Povídka o obrazu císaře Františka Josefa I. was published in the Kiev weekly Čechoslovan on 17 July 1916 and described the owner of a paper-shop, Mr. Petiška from Mladá Boleslav, who traded pictures of the emperor in Jewish liquor shops and also eagerly hoisted the flag on official state holidays. Unfortunately a tomcat emptied his bladder on the pictures and made them unsellable. The story was picked up by the Austrian intelligence services and led to an investigation in absentia of the author, for high treason (Hochverrat) and defamation of His Imperial Majesty (Majestätsbeleidigung). The case was jointly investigated by c.k. policejní ředitelství and the k.u.k. Divisionsgericht in Vienna.

Thanks to this story Jaroslav Hašek earned a place in the book "The treacherous activities of Austrian Czechs abroad", published by c.k. policejní ředitelství in 1917[a]. It named around 1,000 people, and the author of the tomcat story was in good company: Professor Masaryk, future Czechoslovak president Eduard Beneš, Hašek's friend Vlasta Amort, and more surprisingly James Joyce. How the latter became involved with "Austrian Czechs" is however mindboggling. According to the police records his nationality was unknown, he lived in Zürich and was classed as politically suspect!

Credit: Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Šerák, Břetislav Hůla, Jan Morávek, Jan Vaněk, Bohumil Vlček, Jaroslav Kejla, František Skřivánek, Franta Hofer, VÚA, ÖStA

Literature

- Májové výkřiky, ,1903

- Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, ,1911 (banned), 1912 (re-issued)

- Trampoty pana Tenkráta, ,1912

- Průvodčí cizinců a jiné satiry z cest i domova, ,1913

- Můj obchod se psy a jiné humoresky, ,1915

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917

- Dva tucty povídek, ,1920

- Pepíček Nový a jiné povídky, ,1921

- Mírová konference a jiné humoresky, ,1922

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl II. Na frontě., ,1921-1922

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl III. Slavný výprask., ,1922

- Pevnost,

- Agadir,

- Z Karlína do Bratislavy parníkem Lanna 8 za 365 dní, ,29.12.1921

- Malá zoologická zahrada, ,1950

- Črty, povídky a humoresky z cest, ,1955

- Loupežný vrah před soudem, ,1958

- Dědictví po panu Šafránkovi, ,1961

- Zrádce národa v Chotěboři, ,1962

- Fialový hrom, ,1962

- Utrpení pana Tenkráta, ,1962

- O dětech a zvířátkách, ,1960

- Galerie karikatur, ,1964

- Politické a sociální dějiny strany mírného pokroku v mezích zákona., ,1963

- Dobrý voják Švejk před válkou a jine podivné historky., ,1957

- Májové výkřiky. Básně a prózy., ,1972

- Zábavný a poučný koutek Jaroslava Haška, ,1973

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí. Stati a humoresky z dob války, ,1973

- Velitelem města Bugulmy, ,1966

- Moje zpověď, ,1968

- Franta Habán ze Žižkova I., ,1923

- Franta Habán ze Žižkova II., ,1923

- Ve dvou se to lépe táhne, ,1923-1924

- In memoriam Jaroslava Haška, ,1924

- Z mých vzpomínek na Jaroslava Haška, ,1925

- Ve dvou se to lépe táhne, ve třech hůře, ,1927

- Jaroslav Hašek, ,1928

- Když táhne silná čtyřka, ,1930

- Jaroslav Hašek, zajatec číslo 294217, ,1934

- Jaroslav Hašek doma, ,1935

- Kdo je Jaroslav Hašek, ,1946

- Lidský profil Jaroslava Haška, ,1946

- Jaroslav Hašek v zajetí, ,1948

- Čtvrt století s Jaroslavem Haškem, ,1948

- O životě Jaroslav Haška, ,1953

- Byli a bylo, ,1963

- Přátelé Haškovi a lidé kolem nich, ,1965

- Toulavé house, ,1971

- Znal jsem Haška, ,1977

- The Bad Bohemian, ,1978

- Nikdo za nic nedostane, ,2023

- Stenographische Protokolle - Abgeordnetenhaus, ,29.11.1911

- Hašek Jaroslav, digitalizace,

- Bibliografie Jaroslava Haška, ,1960

- Belonhnungsantrag Jaroslaus Hašek,

- Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920),

- Jak se Jaroslav Hašek učil oficírem, Franta Hofer

- Voják Jaroslav Hašek v Českých Budějovicích, Bohumil Milčan

- Hašek, Jaroslav,

- Podivný Hašek, Jindřích Chalupecký,1991

- Josef Švejk, syn Jaroslava Haška, ,16.8.2016

- Jaroslav Hašek - dobrý voják Švejk, Jan Morávek,1924

- Jaroslav Hašek, Radko Pytlík,1993

- Jaroslav Hašek slovem i obrazem, ,1993

- Lad. Hajek Domažlický a Jaroslav Hašek ..., ,10.5.1903

- Aus dem praktischen Leben, Jaroslav Hašek,7.7.1903

- Letošní Sylvestrovský večer, ,2.1.1906

- Žalár, transcedentální medicina a román., ,2.7.1907

- „Žurnalista“ Hašek, ,2.7.1907

- Zajímavosti z porotní síně, ,23.10.1909

- Zasnoubení, ,23.11.1909

- Zabrávěná sebevrazda, ,10.2.1911

- Zapomenutá kandidatura, ,15.6.1911

- Originelní kandidatura, ,23.6.1911

- Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, ,13.10.1911

- Smutná vzpominka, ,3.11.1911

- Kundmachungen, ,23.11.1911

- Úraz novináře, ,19.1.1912

- Nový pražský starosta, ,20.2.1912

- Jaroslav Hašek, ,16.3.1912

- Der hinausgeworfene Heldensänger, ,31.10.1912

- Ženský odbor Sokola v Turnově, ,10.11.1912

- Zprávy z Turnova, ,24.11.1912

- Čeští kabaretní umělci v Plzni, ,6.9.1913

- Musil sekati led, ,5.2.1914

- Falešný uprchlík z Ruska, ,13.12.1914

- Humoristovy rozmary, ,18.12.1914

- Jak Jaroslav Hašek dělal uprchlíka, ,18.12.1914

- Čestný večer Xeny a Artura Longenových, ,10.2.1915

- Nová kniha humoresek Jaroslava Haška, ,25.2.1915

- Raněný český spisovatel v Č. Budějvocích, ,13.3.1915

- Spisovatel Jaroslav Hašek, ,14.11.1915

- Spisovatel Jaroslav Hašek zajat, ,16.11.1915

- V zajetí, ,15.3.1916

- Jaroslav Hašek v ruském zajetí, ,14.6.1916

- Jaroslav Hašek v ruském zajatí, ,17.6.1916

- Český spisovatel píše ze zajetí, ,19.9.1916

- České vojsko, ,9.2.1917

- Verlustliste Nr. 566, ,4.5.1917

- Hochverräterische Umtriebe von österr. Čechen im Auslande, ,1917 [a]

- Průkopníci, Rudolf Medek,6.4.1918

- Ze starých dokumentů, ,31.7.1918

- Anekdota o Jaroslavu Haškovi, ,5.12.1918

- Jaroslav Hašek zastřelen?, ,14.1.1919

- Nekolik historek o Jaroslavu Haškovi, ,20.2.1919

- Jaroslavu Hašek živ?, ,16.3.1919

- Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona, ,10.4.1919

- Jaroslav Hašek žije?, ,26.2.1920

- Humorista Hašek se vratil, ,20.12.1920

- Jaroslav Hašek zase v Praze, ,20.12.1920

- Čtyřikrát mrtvev a přece živ, ,21.12.1920

- Červená sedma, ,1.1.1921

- Jaroslav Hašek a komunisté, ,6.1.1921

- Divadélko Adria, ,1.11.1921

- Prager Lokalstücke, B.,5.11.1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, Ivan Olbracht,15.11.1921

- Švejk, DRAF,18.11.1921

- Jaroslav Hašek, E. A. Longen,31.1.1922

- Jaroslav Hašek se zlobí, ,23.11.1922

- Jaroslav Hašek mrtev?, Mi. Ma.,4.1.1923

- Spisovatel Jaroslav Hašek mrtev?, ,4.1.1923

- Jaroslav Hašek zemřel, ,4.1.1923

- Jaroslav Hašek zemřel, B.,4.1.1923

- Jaroslav Hašek uemřel, R.K.,4.1.1923

- Jaroslav Hašek, k.,5.1.1923

- U mrtvého geniálního humoristy, Michal Mareš,5.1.1923

- Jaroslav Hašek zemřel, A.V,5.1.1923

- Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein, ,5.1.1923

- Pohřeb spisovatele Jaroslava Haška, ,8.1.1923

- Profil mrtvého druha, Jarmila Hašková,10.1.1923

- K úmrti humoristy J. Haška, ,10.1.1923

- Auf den Tod eines Tschechischen Humoristen, e.e.k.,1923

- Za Jaroslavem Haškem, František Skřivánek,3.2.1923

- In memoriam Jaroslava Haška, ,30.3.1923

- Za mrtvým humoristou, Karel Vaněk,6.1.1924

- Nikoliv anekdota o Haškovi, ,8.1.1924

- Náš film, ,1.2.1924

- Z uzpomínek na Jaroslav Haška, Vincenc Jažlovický,14.8.1924

- Ke characteristice Jaroslava Haška, Ivan Suk,17.9.1924

- Díl I., ,1.9.1924

- Díl II., ,2.9.1924

- Díl III., ,3.9.1924

- Díl IV., ,4.9.1924

- Díl V., ,6.9.1924

- Díl VI., ,10.9.1924

- Díl VII., ,12.9.1924

- Díl VIII., ,13.9.1924

- Díl IX., ,15.9.1924

- Díl X., ,18.9.1924

- Díl XI., ,20.9.1924

- Díl XII., ,22.9.1924

- Díl XIII., ,25.9.1924

- Díl XIV., ,27.9.1924

- Díl XV., ,1.10.1924

- Díl XVI., ,4.10.1924

- Die Börse der Nachrichten, Egon Erwin Kisch,6.12.1925

- Humor v čsl. odboji, ,25.3.1926

- O Jaroslavu Haškovi, Eduard Bass,27.3.1927

- O Jaroslavu Haškovi, Eduard Bass,3.4.1927

- Jaroslaus Hašek, Einj. Freiw. I. R. Nr. 91., ,15.12.1927

- Jaroslav Hašek na Lipnici, Kliment Štěpánek,20.12.1927

- Mé vzpominky na Jaroslava Haška, Kliment Štěpánek,4.1.1928

- Haškova návštěva, Ji-še,9.1.1928

- Hašek, der Dichter und Säufer, Michal Mareš,17.1.1928

- O posledních dnech Jaroslava Haška, Kliment Štěpánek,21.2.1928

- Hrdina Švejk, Viktor Dyk,15.4.1928

- "Hrdina Švejk" Viktora Dyka, ,19.4.1928

- "Švejk“ a senátor Dyk, ,24.4.1928

- Dykův Švejk, ,24.4.1928

- Der Dichter des "Švejk" in Irrenhaus, ,10.9.1929

- Vzpomínky Starodružinníka na Jar. Haška, M. Kříž,9.3.1930

- Kamarádi dobrého vojáka Svejka umirají, ,22.8.1930

- Vzpominky z Ruska na Jaroslava Haška, A. Cechmajstr,5.7.1931

- Jarmila Haškova zemřela, Z,21.9.1931

- Meine Erinnerungen an Jaroslav Hašek, Kliment Štěpánek,29.11.1931

- Hašek naruby, Petr Fingal,22.1.1932

- Rybí jikry, které se dávají vysedět kvočnám, ,20.7.1932

- Hrdinové z dobrého vojáka Švejka se sešli, ,30.10.1932

- Ein Verein der "Freunde des guten Soldat Schweijk", ,9.11.1932

- Schwejk als Reporter, ,23.4.1933

- Jar. Hašek padesátník, Josef Čermák,23.4.1933

- Hašek a Mussolini, ,9.10.1935

- Jaroslav Hašek privat, ,29.8.1935

- Před dvaceti lety ... (I), M. Šešín,24.5.1936

- Před dvaceti lety ... (II), M. Šešín,31.5.1936

- Bolševik Hašek a legionář Brikcius, Vl. Brikcius,30.8.1936

- Vzpominka na T. G. Masaryka, Vincenc Svoboda,1937

- Jaroslav Hašek v legiích a proti nim, A. Cechmajstr,1.8.1937

- Jar. Hašek a legie: od zborovské bitvy až do odchodu, A. Cechmajstr,8.8.1937

- Jaroslav Hašek - feulletonista Rudé armády, ,27.4.1938

- Jaroslav Hašek v Rudé armádě, ,22.5.1938

- Ze vzpomínek na Jaroslav Haška, Egen Erwin Kisch,5.4.1948

- Ze vzpomínek na Jaroslav Haška, V. Choděra,19.8.1949

- Ein großer tschechischer Satiriker, ,24.4.1953

- Jaroslav Hašek - bojovník za socialismus, Zdena Ančík,29.4.1953

- O sebraných spisech Jaroslava Haška, Zdena Ančík,10.9.1955

- Der Vater des "Braven Soldaten Schwejk", ,26.10.1957

- Pamětníci o Haškově životě, Zdeněk Šťastný,15.12.1957

- Stále živý Hašek, Jaroslav Bláha,3.1.1958

- Kde pracoval Hašek, J.N. Ščerbakov,24.1.1963

- Český komisař Jaroslav Hašek, Zdeněk Šťastný,30.4.1963

- S Jaroslavemm Haškem u plukovním komitétu, Josef Pospíšil,1.9.1967

- Jaroslav Hašek a mongolští revolucionáři, Josef Pospíšil,14.7.1976

- Na povel Aurory, ,7.11.1970

- Když Jaroslav Hašek byl novinářem, ,24.12.1982

- Poslušně hlásím..., Ivan Černý,28.11.1989

- Díl. I., ,7.1.1928

- Díl. II., ,14.1.1928

- Díl. III., ,28.1.1928

- Díl. IV., ,4.2.1928

- Díl. V., ,11.2.1928

- Díl VI., ,25.2.1928

- Díl VIII., ,10.3.1928

- Díl IX., ,17.3.1928

- Díl X., ,24.3.1928

- Díl XI., ,21.4.1928

- Díl XII., ,28.4.1928

- Díl XIII., ,5.5.1928

- Díl XIV., ,12.5.1928

- Díl XV., ,19.5.1928

- Díl XVI., ,26.5.1928

- Díl XVII., ,2.6.1928

- Dětství Jaroslava Matěje Františka Haška, ,23.4.1933

- Jaroslav Hašek před vojnou a po vojně, ,27.4.1933

- Jaroslav Hašek - komisař bolševiků, ,7.5.1933

- Hašek jde na vojnu, ,27.5.1933

- Dobrý voják Hašek, ,11.6.1933

- Hašek vstupuje do praktického života, ,18.6.1933

- Hašek inteligentním praktikantem, ,2.7.1933

- Hašek si loučí s drogerií, ,9.7.1933

- Hašek policajtem, ,18.7.1933

- Hašek sebevrahem, ,23.7.1933

- Hašek volebním agitátorem, ,3.8.1933

- Hašek přichází do Vídně, ,15.8.1933

- Hašek cestovatel, ,5.9.1933

- Hašek u hraběte Andrassyho, ,17.9.1933

- Jaroslav Hašek v Uhrách, ,22.9.1933

- Hašek cestovatelem, ,1.10.1933

- Hašek s bratří s maďary, ,15.10.1933

- Hašek mezi krajany, ,26.10.1933

- Hašek začíná psát, ,2.11.1933

- Jaroslav Hašek vstupuje do literatury, ,28.11.1933

- Hašek spisovatelem, ,10.12.1933

- Hašek loupežníkem, ,17.12.1933

- Na pěti sloupečcích: Hašek na toulkách, ,27.12.1933

- Krevní mstitel, ,29.12.1933

- Hašek na návštěvě, ,14.1.1934

| a | Hochverräterische Umtriebe von österr. Čechen im Auslande | 1917 |

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |