Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (286)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (286)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

9. Švejk in the garrison prison | |||

| Obchodní akademie |  | ||||

| Praha II./1780, Resslova ul. 8 | ||||||

| ||||||

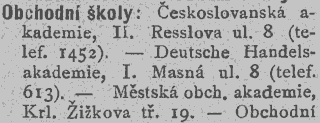

Resslova 1780/8: Českoslovanská akademie obchodní.

Address book from 1910.

Jan Řežábek

, 21.10.1892

Obchodní akademie is mentioned when the author introduces Feldkurat Katz to the reader. He had studied at a commercial academy.

Background

Obchodní akademie is an ambiguous term, but we must assume that Otto Katz studied at one of the two commercial academies in Prague. Because he was Jewish it is at first glance logical to assume that his mother tongue was German and he therefore studied at the German academy. On the other hand the field chaplain was no doubt bi-lingual so the Czech academy must also be considered.

Českoslovanská akademie obchodní in Resslova ulice is all in all the likelier candidate. Hašek himself studied here and this weighs heavily in favour of the latter when analysing which commercial academy the future field chaplain studied at. It should also be noted that some Otto Katz actually graduated from this academy in 1881 and the author may well have been aware of him. Augustin Knesl claimed that this very person was the model of Hašek's literary field chaplain.

Another Otto Katz graduated from the German academy in 1896, but in 1906 he lived in Trieste so it is less likely that Hašek knew him.

Commercial academies as institutions

In Austria commercial academies were institutions that offered three-year (later four-year) education in commerce and accounting. The first of those academies was founded in Prague in 1856 as Prager Handelsakademie, the first with Czech as instruction language was the very Českoslovanská akademie obchodní that was established in 1872. From the beginning they were located in Staré město but in 1892 they moved to Resslova ulice i Praha II. They are still (2020) operating but located in another building in the same street. Commercial academies as institutions to this day exist in Czechia, Slovakia and Austria.

Hašek and the Czechoslavonic Commercial Academy

Jaroslav Hašek studied here from 1899 to 1902 and left with good grades. Here he met some of his best friends, first and foremost Hájek, but also Karel Marek who probably lent his name to the literary Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek. Another fellow student was Jan Čulen who joined Hašek on a longer journeys in 1900 and 1901. It was this education that enabled Hašek to serve as a one-year volunteer in k.u.k. Heer. The institution was one the list of establishments that gave its graduates the right to shortened term of service and other privileges.

On bad terms with the headmaster

In 1909 Jaroslav Hašek wrote he story Obchodní akademie for Karikatury. Here head teacher "Jeřábek", in real life Jan Řežábek[1], is mercilessly pilloried and the piece was censored and was only printed the next year, in a revised version. Jeřábek was even assigned qualities that readers of The Good Soldier Švejk will recognise in Oberst Kraus. In addition the academy is mentioned multiple times in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Studoval obchodní akademii a sloužil jako jednoroční dobrovolník. A vyznal se tak dobře v směnečném právu a ve směnkách, že přivedl za ten rok obchodní firmu Katz a spol. k bankrotu tak slavnému a podařenému, že starý pan Katz odjel do Severní Ameriky, zkombinovav nějaké vyrovnání se svými věřiteli bez vědomí posledních i svého společníka, který odjel do Argentiny.

Sources: Augustin Knesl, Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:Commercial academyenHandelsakademiede

| 1. | Jan Řežábek (1862-1925), "Hofrat" and head of the Czechoslavonic Commercial Academy from 1900 to 1918. |

Literature

| Katz a spol. |  | |||

| |||||

, 1.5.1921

, 1896

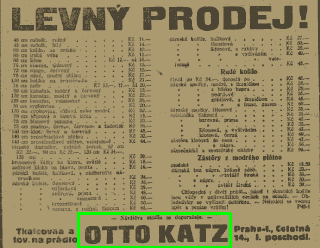

Katz a spol. is mentioned when the author introduces Feldkurat Katz to the reader. The company traded in bills-of-exchange and was owned by Katz's father and his companion. When young Katz took over the business he drove it to bankruptcy within a short time. His father settled with the creditors and moved to North America whereas his companion emigrated to Argentina. Thus the firm continued to exists in the new world, as two incarnations.

Background

Katz a spol. is the author's term for a firm in Prague. At least two companies who traded in Praha at the time were owned by an Otto Katz. None of the two companies traded in bills-of-exchange. In 1983 Augustin Knesl made an attempt to identify Feldkurat Katz and thus the company, and concluded that Katz was born in 1864, was educated at Obchodní akademie and owned a company that went bankrupt in 1923.

The firm that Knesl refers to existed from at least 1918 until 1923 and was a weaver and linen manufacturer in Celetná ulice. The firm advertised widely in 1920 and 1921 and it may be that the author picked the name from these (Jaroslav Hašek was an avid reader of newspapers, including adverts).

Another firm existed from 1893 onwards in Libeň (Královská třída 358) and manufactured rape-seed oil. In 1902 the company is no longer listed but Otto Katz is still the owner of the property, as he is as late as 1932.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Studoval obchodní akademii a sloužil jako jednoroční dobrovolník. A vyznal se tak dobře v směnečném právu a ve směnkách, že přivedl za ten rok obchodní firmu Katz a spol. k bankrotu tak slavnému a podařenému, že starý pan Katz odjel do Severní Ameriky, zkombinovav nějaké vyrovnání se svými věřiteli bez vědomí posledních i svého společníka, který odjel do Argentiny.

Sources: Augustin Knesl, Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

- Obchodní adresář a schematismus pro hlavní město Prahu1927

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a sousedních obcí1896

- Ze vzpomínek bývalých posluchačů Českoslovanské akademie obchodní

- Kolandův adresář VIII. části královského hlav. města Prahy1903

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních1910

- Zapsané firmy19.12.1893

- Zástěry27.1.1918

- Schürzen17.2.1918

- Vyrovnání a konkursy25.1.1923

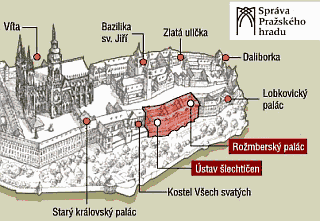

| Ústav šlechtičen |  | ||||

| Praha IV./2-3, U sv. Jíří 1 | ||||||

| ||||||

Ústav šlechtičen is mentioned by the author in his description of the baptism of Feldkurat Katz where a lady from this Institute for Noblewomen was present.

Background

Ústav šlechtičen was an institution for education of daughters of noblemen who were incapable of providing their daughter with an existence that was in line with their rank in society. The foundation was created by Maria Theresa in 1755 and accomodated 30 ladies. It was located in Rožmberský palác at Hradčany. The abbess was always an unmarried lady of the house Habsburg-Lothringen, and from 1894 to 1918 Maria Annunziata, the sister of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, held the position.

On 1 May 1919 the nobility institute was dissolved and the palace transferred to the Ministry of Interior. The building is located on the castle premises, and is today (2015) the property of the Czech state. It recently underwent extensive renovation and is used as a museum and exhibition area.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Křtili ho slavnostně v Emauzích. Sám páter Albán ho na máčel do křtitelnice. Byla to nádherná podívaná, byl u toho jeden nábožný major od pluku, kde Otto Katz sloužil, jedna stará panna z ústavu šlechtičen na Hradčanech a nějaký otlemený zástupce konsistoře, který mu dělal kmotra.

Also written:Institute for NoblewomenenAnstalt für adelige FrauendeInstitutt for adelsdamerno

Literature

| Konsistoř |  | ||||

| Praha IV./56, Hradčanské nám. 16 | ||||||

| ||||||

Konsistoř is mentioned by the author in his description of the baptism of Feldkurat Katz where a representative of the consistory acted as Katz's godfather.

Background

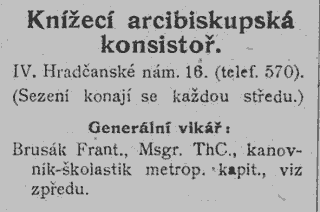

Konsistoř (also called Curia) is a religious council that advises for instance the archbishop or the pope. In this case it is surely talk of the archbishop's consistory at Hradčany (Knížecí arcibiskupská konsistoř). In 1907 the council's address was the archbishop's palace itself, and they held meetings every Wednesday

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Křtili ho slavnostně v Emauzích. Sám páter Albán ho na máčel do křtitelnice. Byla to nádherná podívaná, byl u toho jeden nábožný major od pluku, kde Otto Katz sloužil, jedna stará panna z ústavu šlechtičen na Hradčanech a nějaký otlemený zástupce konsistoře, který mu dělal kmotra.

Also written:ConsistoryenKonsistoriumdeKonsistorietno

Literature

| Seminář |  | |||

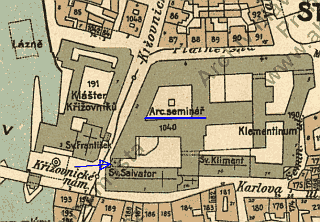

| Praha I./1040, Křižovnické nám. 4 | |||||

| |||||

,1907

Seminář is mentioned 3 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Seminář is mentioned by the narrator in his introduction of Feldkurat Katz's and his illustrious career. The newly converted priest was educated at the Seminary. In the next chapter [I.10,2] he mentions the Seminary in between some drunk drivel.

Background

Seminář most probably refers to Arcibiskupský seminář (The Archbishop's Seminary), an institution for education of catholic priests that still exists. During the times of Jaroslav Hašek the Seminary was located in Klementinum, but it was in 1929 re-located to Dejvice where it is still housed[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Ale jednoho dne se opil a šel do kláštera, zanechal šavle a chopil se kutny. Byl u arcibiskupa na Hradčanech a dostal se do semináře. Opil se na mol před svým vysvěcením v jednom velmi pořádném domě s dámskou obsluhou v uličce za Vejvodovic a přímo z víru rozkoše a zábavy šel se dát vysvětit.

[I.10.2] Počal se hlasitě smát, ale za chvíli zesmutněl a apaticky se díval na Švejka pronášeje: „Dovolte, pane, já vás již někde viděl. Nebyl jste ve Vídni? Pamatuji se na vás ze semináře.“

[I.13] Zatím polní kurát si v katechismu zopakoval, co kdysi v semináři neutkvělo mu v paměti

Also written:SeminaryenSeminardeSeminaretno

| a | Historie a život v semináři |

| U Vejvodů |  | ||||

| Praha I./353, Jilská ul. 2 | ||||||

| ||||||

,25.10.1910

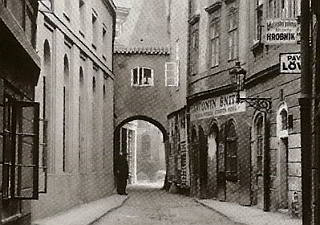

U Vejvodů is mentioned in connection with Feldkurat Katz drinking himself to the ground the night before being ordained as chaplain. This is supposed to have happened "in a descent house with lady service" in a small street behind Vejvodovice.

Background

U Vejvodů is a house and a restaurant in Staré město in Prague and one of the oldest of its kind. It has existed at least since 1560. In 1717 Jan Václav Vejvoda bought the property and the building is named after him. Early in the 20th century Karel Klusáček took over and rebuilt it to become what it was known as until 1990. The house was also for a period the home of a cinema as well as hosting Umělecká beseda (the artist's union).

U Vejvodů still exists as a large restaurant which serves Czech food and Pilsner Urquell. The place is totally changed after the renovation in the 1990's, but is still very popular and relatively affordable considering the location.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Opil se na mol před svým vysvěcením v jednom velmi pořádném domě s dámskou obsluhou v uličce za Vejvodovic a přímo z víru rozkoše a zábavy šel se dát vysvětit.

Sources: Radko Pytlík, Milan Hodík

Also written:VejvodoviceHašek

Literature

| Dům za Vejvodovic |  | ||||

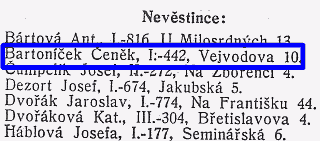

| Praha I./442, Vejvodova ul. 10 | ||||||

| ||||||

Vejvodova ulice, the brothel by the street lamp

Dům za Vejvodovic is mentioned in connection with Feldkurat Katz drinking himself to the ground the night before being ordained as chaplain. This is supposed to have happened "in a very descent house with lady service in a small street behind Vejvodovice".

Background

Dům za Vejvodovic most probably refers to a brothel owned by Čeněk Bartoníček in Vejvodova ulice 10, just a few steps east of U Vejvodů. Bartoníček was in the address book of 1913 listed as owner of the brothel at this address. This is also the only house of pleasure that fits the description in the novel.

In the address book from 1910 a man who carried this name was listed as a "coffee-house" owner in Věnceslava Lužická ulice 29 in Malá strana. This café was entered as a brothel in 1913 but with František Stránský as owner. Bartoníček thus seems to have sold and re-established himself east of the Vltava. Police registers reveal that he lived in Lužická ulice (Prague III/124) already from 1901 and he is registered in Vejvodová ulice from 24 November 1910.

The house itself, also known as Bílý kříž (the white cross) was in 1910 owned by Josef Sobička. To judge by the address books there was no "café" in Vejvodova 10 in 1910 so Bartoníček seems to have started the establishment from scratch.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Opil se na mol před svým vysvěcením v jednom velmi pořádném domě s dámskou obsluhou v uličce za Vejvodovic a přímo z víru rozkoše a zábavy šel se dát vysvětit.

Also written:House behind Vejvodovice;noen

Literature

| Vězeňské kaple |  | ||||

| Praha IV./72, Kanovnická ul. 11 | ||||||

| ||||||

Vězeňské kaple was the scene of Feldkurat Katz' grand sermon for the prisoners in the garrison jail. Here he drunk field chaplain discovered Švejk when the latter started crying during his speech. It ended well for the good soldier who was eventually released and continued in a care-free existence, serving a field chaplain he got on with ever so well.

Background

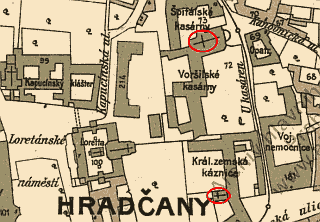

Vězeňské kaple possibly refers Vojenský kostel sv. Jana Nepomuckého at Hradčany. The church belongs to the same building complex as the military hospital, the garrison prison, and the military court. It is easily accessible across the courtyard between the buildings. It shares the address with Voršilské kasárny.

Another place the author might have had in mind is a chapel on the premises of the Royal Country Penitary next door. This was not an army institution, but that will not necessarily have stopped the author from including it in the plot. It also fits the description in the novel more accurately as a house chapel (of the garrison) and a prison chapel is mentioned.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] „Zejtra máme u nás divadlo. Povedou nás do kaple; na kázání. My všichni v podvlíkačkách stojíme zrovna pod kazatelnou. To ti bude legrace!“. Jako ve všech věznicích a trestnicích, tak i na garnisoně těšila se domácí kaple; velké oblibě. Nejednalo se o to, že by nucená návštěva vězeňské kaple; sblížila návštěvníky s bohem, že by se vězňové více dověděli o mravnosti. O takové hlouposti nemůže být ani řeči.

Also written:Prison chapel at HradčanyenGefängniskapell am HradschindeFengselskapellet på Hradčanyno

Literature

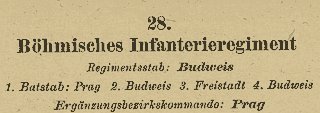

| Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 |  | ||||

| Praha III./132, Pod Bruskou 2 | ||||||

| ||||||

,1908

Vojáci 28. pěšího pluku shromáždění při pohovu u kasáren pod Bruskou (dům čp. 132 na Malé Straně). 1.3.1910.

Heeresergänzungsbezirk Nr. 28

, 1911

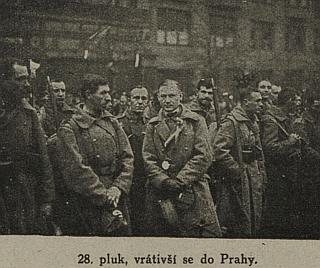

Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 is mentioned 7 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 is mentioned many times in The Good Soldier Švejk. Their name first appears when Feldkurat Katz holds his sermon for the soldiers at Vězeňské kaple. His altar boy was a petty thief from the regiment.

In [II.1] the author mentions an episode where a soldier from the regiment explains how the Hungarians in Szeged ridiculed the Czech soldiers by holding their hands up above their heads.

In [III.1] IR. 28 re-enters the narrative in connection with a report that two of their battalions on 3 April 1915 by Dukla crossed over to the Russians to the tunes of the regiment's orchestra. The regiment was disbanded forever by an Army Order issued by Emperor Franz Joseph I. and their standard was handed over to the army museum in Vienna. The order is read out for the departing soldiers in Királyhida, and so is a related order from Archduke Joseph Ferdinand.

The last mention is in [IV.1] as a spy enters Švejk's cell in Przemyśl. He claims to have served in IR. 28 (although he spoke Czech with a Polish accent).

Background

Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (pěší pluk č. 28) was one of 102 infantry regiments in k.u.k. Heer. It was founded as early as 1698 and was one of the oldest in the entire army. The regiment thus took part in many campaigns and they particularly distinguished themselves by Custoza on 24 June 1866. They also participated in battles during the Napoleonic Wars, for instance at Aspern and Leipzig.

It was a predominantly Czech regiment (95 percent), recruited from Heeresergänzungsbezirk Nr. 28, Prague. They had moved here from Kutná Hora in 1817. Apart from the capital it recruited from Žižkov, Smíchov, Královské Vinohrady, Kladno, Slany, Kralupy a.o.

The regiment's home barracks were at Bruska in Malá Strana. In 1914 only the 2nd battalion and the recruitment district command were located here. The rest of the regiment had since 1912 been garrisoned in Tyrol: staff and the 3rd battalion in Innsbruck and the 1st and 4th battalions in Schlanders (it. Silandro) and Malè respectively. The regimental commander in 1914 was colonel Ferdinand Sedlaczek[a].

During the war

Osmadvacátníci, , 1936

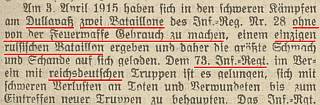

After the outbreak of war, the three battalions from Tyrol[1] were sent to the Eastern Front and took part in the invasion of Russian Poland, including the battle by Komarów on 28 August 1914. The rest of the year and until April 1915 they were fighting north of and in the Carpathians, for instance by Limanowa in December where they suffered severe losses.

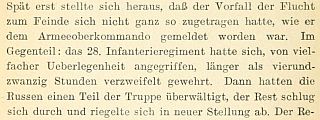

Mass surrender and temporary dissolution

Easter Saturday 3 April 1915 would become the most controversial day in the history of the regiment. At the front section north of Bardejov the bulk of the regiment, probably more than 1,000 men, surrendered after having been partly cut off by numerically superior Russian forces. On 8 April Feldmarschall-Leutnant Josef Krautwald, commander of III. Korps of 3. Armee reported that the regiment had surrendered to a single Russian battalion without firing a shot, that the newly arrived 8th march battalion was the main culprit but that the old core of the regiment was reliable. He claimed that he had received this information from the regiment's commander, a claim that the commander Schaumeier[2] later contested. On 10 April, the commander of 3. Armee, general Svetozar Boroević von Bojna decided to dissolve the regiment temporarily, with effect from the next day. He also informed Archduke Friedrich who on 16 April presented the case for the Emperor. He in turn issued a brief order dated 17 April 1915. It rubber-stamped the decision to temporarily dissolve the regiment, ordered its standard to be deposed in Heeresmuseum in Vienna, and that the decision be made public within the army. On 22 April Emperor Franz Joseph I.'s decree was indeed read out to the troops:

Ich genehmige die vom 3. Armeekommando angeordnete, vorläufige Auflösung des Infanterieregiments Nr. 28 und befehle, dass diese Maßregelung in der Armee allgemein verlautbart, die Regimentsfahne aber im Heeresmuseum deponiert werde. Wien, am 17. April 1915. Franz Joseph

The Emperor's order as reproduced in The Good Soldier Švejk contains some element of the original but is much more verbose and is very close in wording to one of the fake versions that started to appear as leaflets during the summer of 1915. On 11 August 1915 Wiener Zeitung reported that a court in Reichenberg (Liberec) had ordered confiscation of the leaflets[k] but by then the word had spread.

Ersatzbataillon

In the meantime (February 1915) the replacement battalion had been transferred from Prague to Szeged. It was thus one of the first of many Czech regiments that were moved away from their recruitment area that year. The reason for these measures was fears in military circles that the pan-slavic sentiments and increasing dissatisfaction with the war amongst Czechs would be political poison for the soldiers. Already from September 1914, there were reports of poor discipline and dissent when the soldiers left Prague with the 2nd march battalion. Many were reportedly drunk and some demonstrated openly. Commander of the Ersatzbataillon, the pensioned but now re-activated Oberst Josef Krček, was later accused of neglect and for allowing an irresponsible lifestyle amongst the officers. After the regiment's transfer to Szeged, he ordered 6,000 litres of beer a month for the officer's mess![c] In their home city they were replaced by Infanterieregiment Nr. 2 from Brassó (now Brasov in Romania).

Investigations and restoration

, 21.11.1918

The 28th regiment was reconstituted in December 1915 after court investigations in Kassa (Košice) and Temesvár (Timișoara) concluded that the claimed mass desertion was less serious than first believed. During the rest of the war, the regiment operated in Albania, Sarajevo, Carinthia and on the Isonzo front. They took part in the advance on Piave in October and November 1917 (Caporetto) and also participated in the last battle of the war during the days of the final collapse of Austria-Hungary.

The replacement battalion was in 1916 moved from Szeged to Bruck an der Mur where they were garrisoned until the war ended. These were the first soldiers from the now defunct k.u.k. Heer who returned to Prague. Here they were celebrated as heroes, and the regiment was absorbed into the Czechoslovak army using their old number, and streets were named after them.

In history writing

The assessment of the regiment's failure on 3 April 1915 was in the beginning unison: in one way or another they deserted, even defected, traitors to Austrians, Germans and Hungarians, heroes to Czechs. That judgement has in the last 30 years been somehwat modified (more details below), but historian Manfried Rauchensteiner[3] is probably very close when stating: The subsequent investigation of the incident, which took months, brought to light the fact that there had been an overreaction, and that many factors, not least a dismal leadership style, had caused the regiment to surrender and at least not make efforts to sacrifice itself in a difficult situation.

The Austrian-German view

Der Sturz der Mittelmächte, , 1921

Erzherzog Friedrich's army order contained many inaccuracies and falsehoods.

,17.4.1926

In 1921 historian Karl Friedrich Nowak[4] published the book Der Sturz der Mittelmächte (The fall of the Central Powers) where he openly questioned the established narrative. He wrote that the regiment fought for more than 24 hours against a superior enemy before giving up. He added that although some groups no doubt deserted or allowed themselves to be captured, it didn't apply to battalions as units.[f].

Still there is no indication that his observations made any impact on Austrian or Bohemian-German public opinion, nor in anything that was published in German in the inter-war years. Even Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg maintained the essence of the "desertion" story. On the 11th anniversary of the Emperor's army order Salzburger Chronik wrote about the 28th regiment but the narrative had not changed. IR. 28 were still traitors, end of discussion. In September 1939 Kronen-Zeitung in the now Nazi-ruled Austria used the affair in some particularly crude anti-Czech propaganda[h]. This was during the days leading up to the infamous Munich-agreement that forced Czechoslovakia to cede Sudetenland to Nazi Germany).

Over many years the former k.u.k. officer Robert Nowak wrote a manuscript titled Die Klammer des Reichs, probably completed around 1960. It deals with the attitudes of the nations of the Dual monarchy during the war. Nowak tried to have parts of it published in a major Viennese newspaper. The editor refused, explaining that the content was not in line with the public mood! Many historians have since referred to the document but it remains unpublished, stored in Vienna's Kriegsarchiv[i] with copies in the Czech Military Institute.

The Czechoslovak version

, 1.6.1916

, 22.11.1916

The Czech version of events had already started to develop in 1915. The Petrograd newspaper Čechoslovák reported the "Easter Incident". In 1916 the story was embellished further with claims that nearly 2000 men had crossed over, with their arms, luggage and the military band, that parts of the regiment immediately joined the Russians in fighting the Austrians. Later they were allegedly transported to Kiev where they received an enthusiastic welcome. This narrative seems first to have appeared in Corriere d'Italia[l] on 3 March 1916 and on 1 June the Paris-based mouthpiece of the Czech National Council published a variation of the story[b]. It was not signed but was probably written by director Eduard Beneš or editor-in-chief Ernest Denis. The same article came up with a number of improbable claims and extracts from it also appeared in the press of neutral countries, for instance in Switzerland and Norway. It was added that the 11th march battalion had been deliberately sacrificed as revenge, by being forced to fight in the most exposed sectors of the Isonzo-front. 1000 men at the age 18 to 20 had allegedly been slaughtered, only a handful survived. The news item about the 11th march battalion is said to have originated in the Italian press. Parts of content was reproduced in Čechoslovan on 30 October 1916, quoting the Edinburg publication Everyman[j]. This was at a time when Jaroslav Hašek contributed to the newspaper so he would have been aware of the content. More or less the same story appeared in the Bohemia's case for independence (1917)[5], a book written by Edvard Beneš that was also published in French and Italian.

In inter-war Czechoslovakia the desertion myth was obviously cultivated for different reasons than in Austria. The 28th regiment were celebrated as heroes who had voted with their feet against Habsburg oppression and for an independent Czechoslovak state. The deluge of legionnaire literature further underpinned this narrative and also partly credited the desertion to agitators from Družina (the predecessor the Legions) who were operating in the area when the affair took place.

General Kunz

General Jaroslav Kunz. Probably the first Czech who openly questioned the official narrative of the desertion of IR. 28.

The only dissenting voice from this period seems to have been pensioned general Jaroslav Kunz[6]. In 1931 he published an article called Falešná legenda in the weekly Pestrý týden where he openly questioned the official Czechoslovak and Austrian versions of the affair. Referring to Nowak's book he went further in his analysis, investigating witness accounts from the trial. His conclusion was that although desertions no doubt took place, there was no reason to believe that the battalions deserted without putting up a fight. He pointed out that there were many war graves of 28ers in the area of the battle, that few of those captured on 3 April 1915 ever joined the Legions and when prisoners were returned after the Brest-Litovsk treaty in March 1918, the returning soldiers were not punished for desertion. Later that year Falešná legenda appeared as a chapter in the book Tajnosti rakouského generálního štábu (The secrets of the Austrian general staff). Here Kunz added more observations and noted how hostile the reaction to his article had been, be it in Czechoslovakia or Austria.

General Klecanda who led the Družina reconnaissance patrols in the area where the 28th regiment was operating during Easter 1915 reacted immediately and called Kunz "unpatriotic". Kunz also reveals that his article was refused by many newspapers until Pestrý týden finally agreed to print it in February 1931.

Karel Pichlík

Karel Pichlík, Historie a vojenství, 1959

Under Communist rule there was little interest in revising the established narrative. The most useful study from this period was surely that of the well known historian Karel Pichlík who in 1959 published a detailed and well documented paper in Historie a vojenství.[e] He does not refute the allegations of collective betrayal but takes aim at the agenda of "bourgeois" Czechoslovakia and by the Austrian "imperialists". He takes issues with Kunz and states that Kunz merely proved that the regiment put up some resistance. Drawing on many sources he convincingly documented the anti-Austrian sentiments amongst the Prague recruits both from IR. 28 and k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 and how it manifested itself as open dissent. Predictably he fitted the narrative to the political dogma that prevailed at the time.

The Dukla incident mirrored in Švejk

The popularity of The Good Soldier Švejk has also played a part in spreading the myths about the Prague house regiment. This was however not the work of Hašek, despite the fact that he on half a page disseminated both Austrian and Czechoslovak disinformation. He simply replicated the information that was in circulation when he wrote the novel, including the claim about the regiment's orchestra joining the desertion. In 1957 his biographer Jaroslav Křížek repeated it all and he was surely not alone.

Recent publications

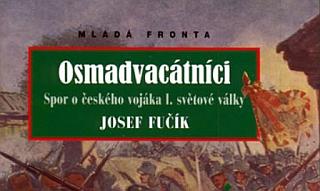

The recent reassessment of the history of IR. 28 seems to have started with Josef Fučík[7] who in 1994 published a paper about the regiment in the journal Střední Evropa. Later he wrote the book Osmadvacátníci (The Twentyeighters, 2006) which is an explicit rehabilitation of the regiment, to the extent that even the sleeve contains quotes from Nowak. The book is rich in details and very well researched. In 2011 Richard Lein followed up with more or less similar conclusions in his Pflichterfüllung oder Hochverrat. "Rehabilitation" in this context does not necessarily mean that the accusations of treason were entirely unfounded, simply that many of the claims made about IR. 28 and the events on 3 April 1915 were false and have since served political purposes.

That said both books suffer from the weakness that they underplay the fact that AOK's distrust of Czech regiments to a degree was justified. Many incidents had preceded that of IR. 28 and the conclusion of historian Manfried Rauchensteiner probably sums it up: it was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Hašek and IR. 28

There were no units from IR. 28 in Trento in 1906, the year that Hašek (according to Menger) enrolled with the regiment.

, 1906

Apart from the author's own IR. 91 and its subordinated units IR. 28 is no doubt the military unit that is most often mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk. This could be explained by the fact that the author himself was from Prague and thus would have known many who served in the regiment. Václav Menger even claimed that Hašek served with them in 1906 for a few weeks until he was superarbitrated. Closer investigations however reveal that this can't be true. See Trento for a background. It is however striking that this garrison features in all three versions of The Good Soldier Švejk but there is scant evidence that Hašek ever visited. Perhaps the inspiration comes from his acquaintances in IR. 28? The major part of the regiment was stationed in Trento from 1895 to 1899 and again in 1911 and 1912 so many men of his age from Prague would have served here.

From Hůla's explanations to Švejk (1951). © LA-PNP

Hašek would, as a volunteer in České legie, have known several of the former soldiers from the 28th regiment. One such person was Břetislav Hůla who according to the service record from the Legions was captured by Dukla on 3 April 1915. Why the document states Dukla instead of Stebnícka Huta is a not known but Austrian loss lists confirm that when Hůla went missing he served in the 10th company (3rd battalion). This battalion was indeed part of the fateful battle. Hůla himself wrote about IR. 28 in his explanations to The Good Soldier Švejk (published in 1953) and states that "without offering serious resistance all three battalions let themselves get captured by much weaker Russian forces".

In the newspapers?

At least two of the historians who have touched on the alleged desertion of IR. 28 claimed that newspapers started to write about the affair already in 1915 but without naming any concrete examples. The two are Josef Fučík and Manfried Rauchensteiner, quoting the unpublished paper by Robert Nowak Die Klammer des Reichs. Searches in the digital libraries of Austria and Czechia do however not show a single hit on the issue. The Austrian Reichsanzeiger is supposed to have printed a news item on this[g] but such a newspaper can't be identified. A similar German/Prussian Reichsanzeiger did exist but this paper shows no trace of any news about IR. 28. It also appears strange that censorship allowed these stories to be printed at all as they would damage the delicate and by now deteriorating relation between the nations of Austria-Hungary. So there is still research to be done (Hungarian newspapers have not been consulted).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Zrzavý ministrant, dezertér z kostelnických kruhů, specialista v drobných krádežích u 28. pluku, snažil se poctivě vybavovat z paměti celý postup, techniku i text mše svaté.

[II.1] Od vedlejšího stolu řekl nějaký voják, že když přijeli do Segedina s 28. regimentem, že na ně Maďaři ukazovali ruce do výšky.

[II.2] Černožluté obzory počaly se zatahovat mraky revoluce. Na Srbsku, v Karpatech přecházely bataliony k nepříteli. 28. regiment, 11. regiment. V tom posledním vojáci z píseckého kraje a okresu.

[II.3] „Případ vašeho černocha Kristiána,“ řekl jednoroční dobrovolník, „třeba promyslit i ze stanoviska válečného. Dejme tomu, že toho černocha odvedli. Je Pražák, tak patří k 28. regimentu. Přece jste slyšel, že dvacátý osmý; přešel k Rusům.

[III.1] Potom Švejk počal mluvit o známých rozkazech, které jim byly přečteny před vstoupením do vlaku. Jeden byl armádní rozkaz podepsaný Františkem Josefem a druhý byl rozkaz arcivévody Josefa Ferdinanda, vrchního velitele východní armády a skupiny, kteréž oba týkaly se událostí na Dukelském průsmyku dne 3. dubna 1915, kdy přešly dva batalióny 28. pluku i s důstojníky k Rusům za zvuků plukovní kapely.

[III.1]Armádní rozkaz ze dne 17. dubna 1915:

Přeplněn bolestí nařizuji, aby c. k. pěší pluk čís. 28 pro zbabělost a velezrádu byl vymazán z mého vojska. Plukovní prapor budiž zneuctěnému pluku odebrán a odevzdán do vojenského musea. Dnešním dnem přestává existovat pluk, který, otráven mravně z domova, vytáhl do pole, aby se dopustil velezrády.František Josef I.

[III.1]Rozkaz arcivévody Josefa Ferdinanda:

České trupy během polního tažení zklamaly, zejména v posledních bojích. Zejména zklamaly při obraně posic, ve kterých se nalézaly po delší dobu v zákopech, čehož použil často nepřítel, aby navázal styky a spojení s ničemnými živly těchto trup. Obyčejně vždy směřovaly pak útoky nepřítele, podporovaného těmito zrádci, proti těm oddílům na frontě, které byly od takových trup obsazeny. Často podařilo se nepříteli překvapit naše části a takřka bez odporu proniknout do našich posic a zajmouti značný, velký počet obránců. Tisíckrát hanba, potupa i opovržení těmto bídákům bezectným, kteří dopustili se zrady císaře i říše a poskvrňují nejen čest slavných praporů naší slavné a statečné armády, nýbrž i čest té národnosti, ku které se hlásí. Dřív nebo později zastihne je kulka nebo provaz kata. Povinností každého jednotlivého českého vojáka, který má čest v těle, je, aby označil svému komandantovi takového ničemu, štváče a zrádce. Kdo tak neučiní, je sám takový zrádce a ničema. Tento rozkaz nechť je přečten všemu mužstvu u českých pluků. C. k. pluk čís. 28 nařízením našeho mocnáře jest již vyškrtnut z armády a všichni zajatí přeběhlíci z pluku splatí svou krví těžkou vinu.Arcivévoda Josef Ferdinand

[IV.1] Já jsem sloužil u 28. regimentu a hned jsem vstoupil k Rusům do služby, a pak se dám tak hloupé chytit.

[IV.1] ... snad ty si vzpomeneš na někoho, s kým si se tam tak stýkal, rád bych věděl, kdo tam je od našeho 28. regimentu?

| 1. | The Prague-based 2nd battalion was dispatched to the Serbian front by the Drina as part of 9. Infanteriedivision. In February 1915 they were moved to the Carpathians, but were still detached from the rest of the regiment. |

| 2. | Florian Schaumeier, Austrian officer who served with the 28th regiment from 1903 to 1915. In 1914 he was commander of the replacement battalion, rank Major. By March 1915 he was regimental commander but was transferred to Infanterieregiment Nr. 11 after the regiment was dissolved. He later became commander of the regiment on the Italian front. In 1917 he was ennobled, taking the predicative name von Anderschell. |

| 3. | Manfried Rauchensteiner (1942-), Austrian historian regarded as one of the leading experts on the Dual Monarchy and its role in World War I. Former director of Herresgeschichtliches Museum. |

| 4. | Karl Friedrich Nowak (1882-1932), Austrian journalist, publisher and historian who during the war worked for Kriegspressequartier. From 1916 he had access to Feldmarschall Conrad and the general staff. |

| 5. | Edvard Beneš, Bohemia's case for independence, 1917. This book is a political pamphlet that aimed to influence decision-makers in the allied capitals towards accepting the need to break up Austria-Hungary. To achieve his goal Beneš didn't shy away from exaggerations, falsehoods and even conspiracy theories. From pages 57 and 58: To complete this sketch it is necessary to recite the tragic tale of the surrender of the 28th Czech Regiment of Prague, which caused such a stir a year ago, and which illustrates best of all the true spirit of the Czech nation. This regiment had surrendered to the Russians in the Carpathians on April 3rd, 1915, with all their arms and baggage, not even excepting their military band. In this way nearly 2000 men went over to the Russians and the greater part of the regiment commenced immediately to fight the Austrians. After that they were transported to Kieff, where they were received with enthusiasm. The Emperor, in the Order of the Day read to all the soldiers, dishonoured for ever this regiment, ordered it to be dissolved, and its colours placed in the military museum in Vienna. Connected with this incident there is a very painful story for the Czechs, which was enacted on the Italian front, and which has since been mentioned in the Italian Press. The news of the dissolution of the 28th Regiment had everywhere made a great stir abroad and had given the lie to all the Austrian gossips, who were pretending that everything was going well with the Empire. It had also provoked sentiments of revolt among the Czechs in Bohemia and Moravia. The military authorities of Vienna, therefore, determined to correct this impression and to revenge themselves on the Czechs in the most brutal manner. Last autumn they formed a new battalion, the 28th Regiment, composed exclusively of young men of twenty; they were sent to the Isonzo front and without pity or regard, and without the slightest scruple were exposed to the most murderous Italian artillery fire near Gorizia. Only eighteen soldiers survived the massacre, the rest of the thousand young men remained on the battlefield. Immediately afterwards, the Emperor caused a new Order of the Day to be read to the army, proclaiming that the disgrace of the 28th Regiment of Prague was atoned for by the sacrifice of this regiment on the Isonzo. |

| 6. | Jaroslav Kunz (1869-1933), Austrian, later Czechoslovak military lawyer and general. From 1915 to 1918 war he was head of the Divisional Court in Vienna, in Czechoslovakia he held several positions in the ministry of law. He wrote several books about where the theme was the Austro-Hungarian military and judiciary and their relation to Czechs matters. |

| 7. | Josef Fučík (1932-2018), Czech military historian who specialised in World War I. |

Literature

- IR 28 - bojová cesta2014

- Historie c.a k. pěšího pluku č. 28

- Přechod 28. Pražského pluku k rusům1925

- Bohemia's case for independence1917

- Das Verhalten der Tschechen im Weltkrieg1918

- Předání praporu 28. pěšího pluku do Vojenského historického muzea ve Vídni

- Slovenský Zborov1934

- Tajnosti rakouského generálního štábu1931

- Pražský pěší pluk č. 28 v tažení 1914 - 19151995

- Pražský pěší pluk č. 28 na italské frontě 1915 -1918Josef Fučík8.1996

- Jaké byly osudy 28. pěšího pluku během I. světové války?

- DeserteureLudwig Rege33.1.1921

- 28. pluk "Pražské děti"1932

- S osmadvacátníky za světové války1936

- Pravda o Čechách a Praze30.12.1914

- Potrestaný 28. pluk2.6.1915

- Zprávy z rodného kraje4.6.1915

- Jak byl zajat pražský 28. pluk13.10.1915

- Zrušení 28. a 36. pluku29.11.1915

- Výtečné drženi se 11. pochodového praporu c. a k. péšibo pluku čis. 2816.4.1916

- Češi v rakouské armádě28.4.1916

- Češi v rakouské armádě3.5.1916

- K historii 28. pluku23.5.1916

- Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 2820.10.1917

- Das Verhalten des Tschechen im Kriege10.5.1919

- Historický dokument22.8.1924

- Der Armeebefehl vom April 191517.4.1926

- Zur versuchten Ehrenrettung des ehem. I.R. 28 (1)Fritz Kosmath11.6.1926

- Zur versuchten Ehrenrettung des ehem. I.R. 28 (2)Fritz Kosmath18.6.1926

- Ein Ehrenrettungsversuch für das tschechische Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 2827.4.1926

- Wieder die 28er?3.3.1931

- Die Achtundzwanziger7.3.1931

- Osmadvacátníci a česká družinaEduard Stehlík1.5.1990

- Legenda o dezercii pražského 28. pešieho pluku v Karpatoch27.9.2008

- Pražské děti nezradilyPavel Bělina19.6.2018

- Der Oberste Kriegsherr und sein Stab1908

| K.u.k. Militärgericht Prag |  | ||||

| Praha IV./214, Kapucínská 2 | ||||||

| ||||||

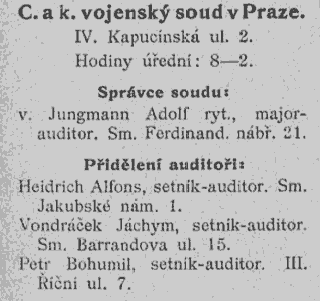

Address book from 1907

K.u.k. Militärgericht Prag the final part of [I.9] takes place here, during the process of transferring Švejk from the garrison prison to Feldkurat Katz. Head of the court was Auditor Bernis. See also Posádková věznice.

The court was first mentioned by the angry policeman at c.k. policejní ředitelství who wishes the devil may take Švejk. If the dares to appear once more he will be sent sraight to the military court.

In [II.2] the court is mentioned again as this is where Pepík Vyskoč was sentened.

Background

K.u.k. Militärgericht Prag was the military court of the Prague-based 8th army group. The court was located at Hradčany in the same building complex as the garrison prison and the military hospital. The k.k. Landwehr court was also located here. An article in Prager Tagblatt also mentions a brigade court, but it is not clear how these administrative subdivisions worked. To judge by newspapers reports from 1914 Hauptmann G. Heinrich led the court[a]. The address book of 1912 lists Major Josef Plzák as the highest ranking officer. His assistant was Oberleutnant Vladimír Dokoupil.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the miltary court is also part of the plot and to a higher degree than in the novel. An auditor handles Švejk's case but he is not named. The narrator also explains how the Austro-Hungarian military judiciary works.[1]

V duchu opustil hradčanský vojenský soud a mysl jeho zaletěla na Vinohrady do malého krámku, svezla se po obraze Františka Josefa a vyhledala pod starou postelí dvě morčata. Švejk k smrti rád pěstoval morčata. A jich osud byl také jedinou chmurou zde.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Vyšetřující auditor Bernis byl muž společnosti, půvabný tanečník a mravní zpustlík, který se zde strašně nudil a psal německé verše do památníků, aby měl pohotově vždy nějakou zásobu. Byl nejdůležitější složkou celého aparátu vojenského soudu, poněvadž měl tak hrozné množství restů a spletených akt, že uváděl v respekt celý vojenský soud na Hradčanech. Ztrácel obžalovací materiál a byl nucen vymýšlet si nový. Přehazoval jména, ztrácel nitě k žalobě a soukal nové, jak mu to napadlo.

[II.4] Když jsem seděl u garnisonsgerichtu, tak se ve vedlejší cimře jeden voják přiznal, a jak se to vostatní dozvěděli, tak mu dali deku a poručili mu, že musí svý přiznání vodvolat."

Also written:Military courtenC.a k. vojenský soudczMilitærdomstolenno

Literature

| a | Desertion | 18.10.1914 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Policejní komisařství XIII. |  | |||

| Libeň/185, Stejskalova ul. - | |||||

| |||||

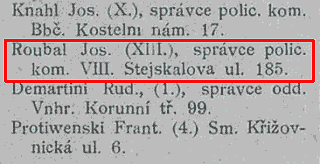

Policejní komisařství XIII. is mentioned by Švejk when Auditor Bernis asks him why he has ended up in the garrison prison. Švejk tells him that he doesn't know, just like the two year old who had walked from Vinohrady to Libeň and was locked up at the local police station. The analogy is that Švejk was also a foundling, just like the two-year old child.

Background

Policejní komisařství XIII. was the police station in Libeň, Prague's police district number 13. It was located in Stejskalova ulice 185 and the station's head in 1906 was chief commissioner Josef Roubal.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] „Poslušně hlásím, že to mohu vysvětlit náramně jednoduchým způsobem. U nás v ulici je uhlíř a ten měl úplně nevinnýho dvouletýho chlapečka a ten se jednou dostal pěšky z Vinohrad až do Libně, kde ho strážník našel sedět na chodníku. Tak toho chlapečka odved na komisařství a zavřeli je tam, to dvouletý dítě. Byl, jak vidíte, ten chlapeček úplně nevinnej, a přece byl zavřenej.

Literature

| K.k. Landwehr |  | ||||

| Wien I./-, Schillerplatz 4 | ||||||

| ||||||

,1914

The recruitment districts of Landwehr

, 1913

K.k. Landwehr is first mentioned in the cell at Posádková věznice when Švejk doesn't return because Feldkurat Katz has chosen him as his servant. A Landwehr soldier with a vivid imagination was of the opinion that he had been taken to Motolské cvičiště to be executed.

In [II.1] when an old landverák (home defence soldier) at the station in Tábor explained to a sergeant the meaning of the word miláček (that Švejk had addressed him with). Later in the chapter the author for the first time mentions a Landwehr regiment: k.k. Schützenregiment Nr. 21.

In [II.2] k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 is implicitly referred to as this is where Toníček Mašků was called up to. Later in the chapter Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek mentions k.k. Landwehr patrols and because the plot is now set in Budějovice the unit in question is k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29.

A curiosity is the fictive k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 64 that Feldoberkurat Lacina mentions on the train from Budějovice to Királyhida in [II.3].

Background

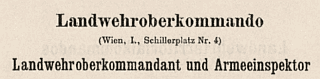

K.k. Landwehr (lit. Land Protection) was the territorial army in Cisleithania, a force that was created in 1868 after Ausgleich. Their Hungarian counterpart was Honvéd. Landwehr reported to Ministerium für Landesverteidigung and was rather a regular fighting force than a pure territorial army/reserve force. Their units were not associated with k.u.k. Heer, had their own barracks and infrastructure, even their own military academies. The term of service was two or three years, and the arrangement with one-year volunteers functioned roughly like in the common army. ,1914

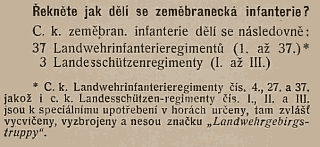

Landwehr consisted of 37 infantry regiments but as opposed to k.u.k Heer the numbers of recruitment districts didn't always correspond to those of the infantry regiments. There was for instance a Landwehrergänzungsbezirk Nr. 38 (Beroun) but no corresponding k.k. Landwehr infantry regiment. Landwehr also contained artillery and cavalry units but had no fortresses. The infantry regiments were smaller than their counterparts in k.u.k. Heer, consisting mostly of three instead of four battalions. Because of the lower number of regiments the recruitment districts were larger than those of the common army. Drafting of recruits was however coordinated and the men were divided between k.u.k. Heer and Landwehr, drawn by lot. At army corps level there was also some co-ordination as both the common army and Landwehr reported to the same Korpskommando.

The k.k. Landwehr high command was located in the building of the Ministry of Justice at Schillerplatz in Vienna. From the district of Landwehrterritorialkommando Prag hailed five Landwehr regiments (names according to Schematismus): Nr. 6 Eger, Nr. 7 Pilsen, Nr. 8 Prag, Nr. 28 Pisek and Nr. 29 Budweis. The number of infantry regiments in k.u.k. Heer in the same area was eight.

During the war

Ehrenhalle des k. k. Landwehr, , 1916

Landwehr in Bohemia were mobilised already at the start of the war. As part of 8. Korps with HQ in Prague 21. Landwehr-infanterievisision was sent to the front against Serbia were they suffered huge losses and in addition were partly blamed for the failed invasions of Serbia. In February 1915 the unit was sent to the Carpathians where other k.k. Landwehr troops from Bohemia already were fighting.

Like the Czech regiments in k.u.k. Heer the reserve battalions from k.k. Landwehr in Bohemia were relocated to non-Czech parts of the empire. This happened in the autumn of 1914 and the first half of 1915, a step that was taken due to the feared disloyalty of Czech recruits (not entirely unfounded). Examples were k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 from Pilsen that was relocated to ethnic German Rumburk and k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 28 from Písek that already in late 1914 were moved to Linz.

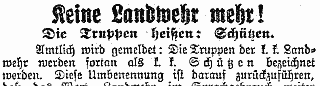

K.k. Landwehr ⇒ K.k. Schützen

, 4.4.1917

In April 1917 all k.k. Landwehr units were renamed k.k. Schützen. The justification was that the new name better reflected that Landwehr were indeed fighting units on level with k.u.k. Heer and not a second line home defence as the former name indicated. The Imperial decree deciding the name change was issued on 19 March 1917, published in Verordnungsblatt für die k.k. Landwehr on 4 April.[a]

Hašek and Landwehr

Jaroslav Hašek would obviously have known and been in contact with k.k. Landwehr throughout. In The Good Soldier Švejk Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek tells Švejk about the conflicts with Landwehr in Budějovice. In this setting it would have been k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 who were garrisoned here. At the end of his stay here he might also have been in touch with k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 6 from Eger (now Cheb) who were moved at the end of May 1915. Parts of this regiment were even housed in Mariánská kasárna, but probably only after IR. 91 vacated it. Two of Hašek's closest friends served with Landwehr: Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj (LIR 6 and LIR 7) and Václav Menger (LIR 28).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.9] Nějaký pihovatý voják od zeměbrany, který měl největší fantasii, rozhlásil, že Švejk střelil po svém hejtmanovi a že dnes ho odvedli na motolské cvičiště na popravu.

[II.1] „Was ist das Wort: milatschek?“ obrátil se šikovatel k jednomu ze svých vojáků, starému landverákovi, který podle všeho dělal svému šikovateli všechno naschvál, poněvadž řekl klidně: „Miláček, das ist wie Herr Feldwebel.“

[II.2] „U nás byl taky jeden takovej nezbeda. Ten měl ject do Plzně k landvér, nějakej Toníček Mašků,“ povzdechla si babička, „von je vod mojí neteře příbuznej, a vodjel.

[II.2] ...dá se chytit landveráckou nebo dělostřeleckou patrolou v noci...

[II.2] ,Prokristapána,` slyšel jsem ho jednou hulákat na chodbě, ,tak už ho potřetí chytla landverácká patrola.

[II.2] Hejtman Spíro udeřil pěstí do stolu. "Zeměbrana vykonává službu v zemi v čas míru."

Literature

- Schematismus der k.k. Landwehr (s. 1)1914

- Handbuch für den Infanteristen des k.u.k. Heeres, sowie der k. k. Landwehr1914

- Z historie III. zeměbrany v Předlitavsku

- Historie čáslavských regimentů

| a | Verordnungsblatt für die k.k. Landwehr | 4.4.1917 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

9. Švejk in the garrison prison | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 14.5.2024 |