This website is dedicated to The Fates of the Good Soldier Švejk in the World War*, written in 1921 and 1922 by Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923). The Good Soldier Švejk, as the novel's title is often shortened, is regarded as a satirical masterpiece and a pioneer of anti-war literature. Bertolt Brecht is reported to have named it one of the three most important novels of the century and wrote a play based on the book. Max Brod compared it to Don Quijote by Cervantes. Joseph Heller and his Catch 22 is often mentioned in the same breath as Švejk, along with Rabelais, Dickens and Twain. The Good Soldier Švejk has been translated into 54 languages (59 if variations like American English are counted) and is arguably the best-known novel written in Czech ever.*) A literal translation of the title.

Stupidity uncovered

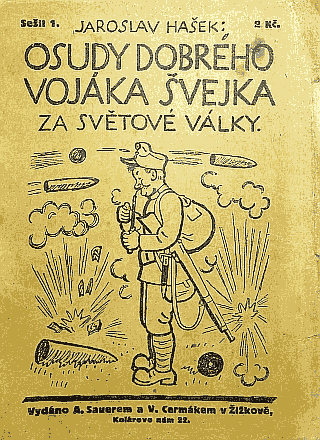

The cover of the first instalment from March 1921, drawn by Josef Lada. This is the only drawing of Švejk that Hašek ever saw. The better known rotund version appeared on 11 November 1923 in 'České Slovo'. Picture courtesy of Richard Hašek, the author's grandson.

Jaroslav Hašek's satire is stinging, at times base but never vulgar, but first and foremost to the point. What strikes the reader most is the lack of respect for institutions and authority. It is not a coincidence that the novel on several occasions has been banned and censored. The instances that have reacted this way have felt their sore toes thread on and for good reasons. Subversive and anti-authoritarian literature often provoke this kind of reaction and The Good Soldier Švejk illustrates the point well. Many readers associate the novel with humour first and foremost, but the message is serious and not the least timeless. The sting is directed against systems created by humans, against people who abuse their positions within these power structures for personal gain or simply toe the line because of their limited horizon, selfishness, fear, stupidity, or the most tragic reason of all: the lack of alternatives. Corruption and abuse of power are by no means limited to the era and geographic region that Hašek described - it is a phenomenon that is deeply ingrained in human nature. The Good Soldier Švejk will therefore be relevant as long as human beings exist on earth. The novel has strong geographical, historical, and cultural ties to Central Europe, but this does not make it less universal.

Setting

The Good Soldier Švejk is set at the start of World War I. It begins with the news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 and ends at the eastern front in current Ukraine in the summer of 1915. Due to the author's early death, the novel was never completed, despite Karel Vaněk writing two more volumes. These are by most experts and readers deemed inferior and scarcely any translation exists.

Švejk

The main character of the novel, Josef Švejk, was a dog trader from Prague, then part of Austria-Hungary. He made a living by selling dogs whose pedigrees he falsified, and he also likes to say that he was dismissed from the army due to idiocy. Note that this is information he reserves for his encounters with the authorities. Otherwise, he had a gentle, charming, and disarming way about him, his mental horizon was seemingly limited, his moral substance appeared to be dubious, and he distinguished himself by producing endless anecdotes, some of them quite unsavory. The stories were often his way of wriggling himself out of difficult situations. He was very good at talking, always had an answer or explanation ready, and was never caught off balance. Despite him not appearing to be clever, he no doubt had a good memory and had read a great deal.

Misunderstood idiocy

Švejk in a coloured edition from 1953. Drawn by Josef Lada.

Everyone from academics to the man in the street has since the novel was published discussed if Švejk really was mentally constrained or if he simply played a fool. He could clearly appear stupid when it suited him, but anyone who has read the novel attentively should not be in doubt: in the epilogue to Part One Hašek writes that if the reader had perceived Švejk to be an idiot, the author had failed to convey his message.

The art of survival

Švejk appeared eager to serve his Emperor and was sent to the front to fight the Russians. On his journey there he and the people around him got entangled in innumerable absurd situations. The author uses this as a backdrop for ridiculing the Austro-Hungarian army, the Catholic Church, the police, the judiciary, and not least the Habsburg Empire. But above all, it is the pointlessness of the entire war that is highlighted. Moreover, the book has many more sides to it than anti-authoritarian and anti-war satire. The former anarchist Jaroslav Hašek is obviously political and critical of the society he lives in, he describes this epoch in European history, has a geographical and historical context, gives the reader an idea of the cultural diversity in the region, and the novel is in itself a key work for anyone interesting in Czech or even Central European culture. Besides the serious main message, situation comedy and slapstick are vital parts of Hašek's method. The author is at his best when he describes the absurd situations in the lives of ordinary people, entangled in systems designed to keep them down or destroy them. Švejk survives and uncovers the stupidity with his cunning and wit. Švejk himself was a master in the art of survival "non plus ultra".

Inspired by real life

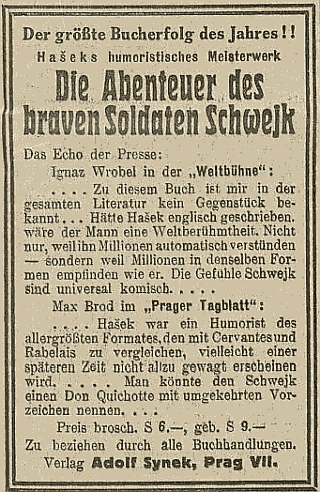

Advert for the German translation of Švejk. 'Die Stunde', 18 June 1926

Despite the literary influences mentioned at the start of this page, The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel that is far more inspired by Jaroslav Hašek's own life and varied experiences than any Cervantes or Rabelais. German writer Kurt Tucholsky (a.k.a Ignaz Wrobel) enthused: in the whole world of literature I know of no novel comparable to this one. Švejk's route to the front is described in detail and largely corresponds to the author's own journey to the battlefield in Galicia in the early days of July 1915. Several of the characters and situations are borrowed directly from the author's own surroundings and experiences. Despite the characters in the novel often being caricatures that never fully correspond to their real-life counterparts, they are still recognisable, even down to biographical details. Although the novel is fiction it may therefore to a degree be read as a historical document. The author's diverse background and extremely wide knowledge is obvious throughout. He provides detailed descriptions of drinking binges, of the Catechism, preparation of meals, historical events, stay in lunatic asylums, religious rituals, dog breeding - most of it based on the author's own experiences.

What was never written

If the author hadn't died before he could finish the fourth of the planned six volumes, we can assume that Švejk, like his creator, would have let himself get captured by the Russians, served in the Legions, worked for the Bolsheviks and eventually ended up in Siberia. Hašek's detailed plan for his good soldier we will never know, but it can be taken for granted that he planned to cover the time in Russia, including the Civil War. To what extent the satire would have been directed against the Legions and the Bolsheviks we can only guess, but to judge from what Hašek actually wrote in Russia (and after his return) they would not have been spared. That said, the calibre would probably not be as heavy as that directed against Austria-Hungary in the first four parts of the novel. The Bugulma stories that appeared in early 1921 indicate a more conciliatory tone. Certain aspects of the Russian revolution are ridiculed, but the author does not show the hostility we know from The Good Soldier Švejk. Hašek didn't like to be asked what he had done in Russia and when the theme was brought up retorted that those who wanted to know better wait for the novel. Unfortunately, he never got to that part...

The return that never happened

For sure Jaroslav Hašek would have let Švejk return unhurt, let him drink his Velké Popovice pivo at U kalicha šest hodin večer, this time with Sappeur Vodička, without the instruments of foreign oppression in the guise of detective Bretschneider poisoning the air with their lingering odour. What he was to experience from mid-July 1915 until his return to Prague in 1920 we may well speculate on, but the author would surely have continued to roughly align the itinerary of his literary hero to his own journey across the Eurasian continent. It may also be that Hašek would have let Švejk experience the same rejection and hostility that he as a "Bolshevik" and "traitor" lived through when he returned to the now independent Czechoslovakia in December 1920.

The motive for creating this website back in 2009 was, despite the novel's and the author's global fame, the lack of internet resources on Švejk and Hašek in any of the nordic languages. I started off in Norwegian only but soon realised that an English translation of the pages would reach a much wider public, so the English version has long been in place. Apart from presenting the author and the novel, existing information is presented in a (hopefully) novel way, and some hitherto unknown information has been added. The novel is replete with references to places, people and institutions - probably around 2,000. The gallery of people and places is so huge that for the dedicated reader it would be useful to have an overview of the often little known people, places and institutions /(now mostly defunct) that the author mentions. I have therefore created lists in all three categories, a task still in progress (2023). The descriptions contain, where possible, links to internet resources and in some cases archive and library material collected by the author of this website.

Literature

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl I., ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl II., ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl III., ,1922

- Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk während des Weltkrieges, ,1926

- Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk während des Weltkrieges, ,1926

- Švejk, egy derék katona kalandjai a világháborúban,

- Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, ,1911 (banned), 1912 (re-issued)

- Dobrý voják Švejk, ,8.7.1911

- Dobrý voják Švejk, ,12.9.1911

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917

- Hledání Josefa Švejka v archivech,

- The Good Soldier Švejk (novel), Maciej Górny,7.10.2015

- Divadélko Adria, ,1.11.1921

- Prager Lokalstücke, B.,5.11.1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, Ivan Olbracht,15.11.1921

- Švejk, DRAF,18.11.1921

- Kapitola literárně-kominická, Karel Vaněk,18.11.1922

- "Švejk“ a senátor Dyk, -,24.4.1928

- "Le Brave Soldat Chvéïk" de Jaroslav Hasek, ,16.4.1932

- Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein., ,5.1.1923

- „Švejk" pokládán za nemravný spis v Německu, ,19.1.1928

- Velký úspěch "Dobrého vojáka Sveika" v Berlíně", ,24.1.1928

- Hrdina Švejk, Viktor Dyk,15.4.1928

- "Švejk“ a senátor Dyk, ,24.4.1928

- Švejkoviny, ,25.4.1928

- Od Švejka - k Masarykovi, J.,27.4.1928

- Švejk a čeští socialiste, ,5.5.1928

- Dyk proti Švejkovi — klerikálové proti legionářům, ,7.5.1928

- Hrdinové z dobrého vojáka Švejka se sešli, ,30.10.1932

- Ein Verein der "Freunde des guten Soldat Schweijk", ,9.11.1932

- Jubilejní vydání Švejka, ,26.4.1936

- Haškův Švejk zdrojem inspirace, ,14.7.1948

- Díl I., ,1.9.1924

- Díl II., ,2.9.1924

- Díl III., ,3.9.1924

- Díl IV., ,4.9.1924

- Díl V., ,6.9.1924

- Díl VI., ,10.9.1924

- Díl VII., ,12.9.1924

- Díl VIII., ,13.9.1924

- Díl IX., ,15.9.1924

- Díl X., ,18.9.1924

- Díl XI., ,20.9.1924

- Díl XII., ,22.9.1924

- Díl XIII., ,25.9.1924

- Díl XIV., ,27.9.1924

- Díl XV., ,1.10.1924

- Díl XVI., ,4.10.1924

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 22.10.2024 |