Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others. This are still listed as fictional because they are literary creations that are only partly inspired by their like-sounding "models".

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are provided as tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

Introduction | |||

| Napoléon Bonaparte |  | |||

| *15.8.1769 Ajaccio - †5.5.1821 St.Helena | |||||

| |||||

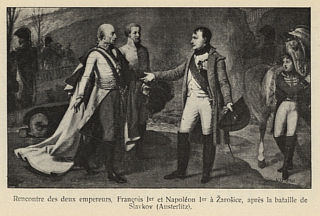

Napoleon

, 1929

Sur le champ de bataille de Slavkov

,1923

Napoléon is mentioned 9 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Napoléon has the honour of being the first person to be mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk. He is also mentioned in [I.1], and later in the novel, he appears several times.

Švejk mentions that Napoléon was five minutes late at Waterloo and his whole reputation subsequently went down the toilet. This was when the train stopped before Tábor in [II.1]. At the end of this chapter, his retreat from Moscow is mentioned.

Background

Napoléon was emperor of France from 18 May 1804 to 6 April 1814. He gradually assembled power in the aftermath of the French Revolution, aided by his unique military talent and many battlefield successes. He conquered and ruled over most of Western and Central Europe and, for a couple of years, also held power in Egypt. A failed campaign in Russia in 1812 weakened his position and laid the foundations for his ultimate defeat at Waterloo in 1815.

Several battles that took place during the Napoleonic wars are mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk: Leipzig, Aspern and Waterloo. Napoléon emerged victorious from the only major battle he was involved in on Czech territory. By Austerlitz (now Slavkov u Brna) Napoleon's army defeated Austrian and Russian forces on 2 December 1805. This battle is by many historians regarded as his greatest military achievement ever.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] Velká doba žádá velké lidi. Jsou nepoznaní hrdinové, skromní, bez slávy a historie Napoleona. Rozbor jejich povahy zastínil by slávu Alexandra Macedonského. Dnes můžete potkat v pražských ulicích ošumělého muže, který sám ani neví, co vlastně znamená v historii nové velké doby.

[I.1] Palivec byl známý sprosťák, každé jeho druhé slovo byla zadnice nebo hovno. Přitom byl ale sečtělý a upozorňoval každého, aby si přečetl, co napsal o posledním předmětě Victor Hugo, když líčil poslední odpověď' staré gardy Napoleonovy Angličanům v bitvě u Waterloo.

[I.10.1] A tak slova Napoleonova "Na vojně se mění situace každým okamžikem" došla i zde svého úplného potvrzení.

[I.14.2] Každý z nich je Napoleonem: "Povídal jsem našemu obrstovi, aby telefonoval do štábu, že už to může začít".

[II.1] Napoleon se u Waterloo vopozdil vo pět minut, a byl v hajzlu s celou svou slávou..."

[II.1] Šel sněhy silnice, ve mraze, zahalen v svůj vojenský plášť, jako poslední z gardy Napoleonovy vracející se z výpravy na Moskvu, s tím toliko rozdílem,...

[II.2] Ta napolionská, potom, jak nám vypravovávali, švédský vojny, sedmiletý vojny

[II.2] Tak se pánbůh na ně rozhněval pro tu jejich pejchu a voni zas přijdou k sobě, až budou si vařit lebedu, jako to bejvalo za napolionský vojny.

[II.3] Dělali to Švédové a Španělé za třicetileté války, Francouzi za Napoleona a teď v budějovickém kraji budou to dělat zase Madaři a nebude to spojeno s hrubým znásilňováním.

Literature

- Jak jsem vystoupil ze strany Nár. sociální, Jaroslav Hašek,14.3.1912

| Alexander the Great |  | |||

| *20.6.356 BC Pella - †10.6.323 BC Babylon | |||||

| |||||

Alexander the Great is introduced by the author as someone that Švejk exceeds the reputation of!

Alexander re-appears several times later in the novel, including in the author's reflections on the officer servant occupation in [I.14]. Here it is revealed that even Alexander had his own Putzfleck.

Background

Alexander the Great was king of Macedonia. The Greek city states had already been united by his father, Philip II of Macedon. Alexander conquered Persia, Egypt and a number of other kingdoms and reached northern India. The conquests led to a rapid spread of Greek culture on the Eurasian continent. Thus he played a major part in the future extending of Greek culture and language.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] Velká doba žádá velké lidi. Jsou nepoznaní hrdinové, skromní, bez slávy a historie Napoleona. Rozbor jejich povahy zastínil by slávu Alexandra Macedonského. Dnes můžete potkat v pražských ulicích ošumělého muže, který sám ani neví, co vlastně znamená v historii nové velké doby.

[I.14.2] Instituce důstojnických sluhů je prastarého původu. Zdá se, že již Alexandr Macedonský měl svého pucfleka.

Also written:Alexandr MacedonskýHašekAlexandr VelikýczAlexander der GroßedeMégas Aléxandrosgr

| Švejk, Josef |  | |||

| |||||

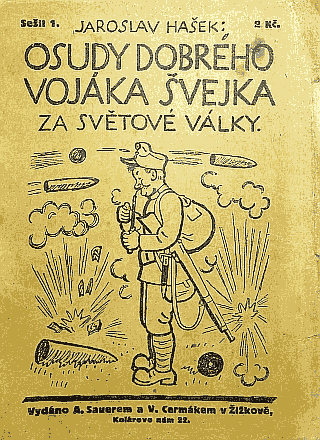

Josef Lada's first drawing of Švejk, 1921

© Josef Lada, 1955

Švejk is mentioned 2001 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Švejk is mentioned in the first paragraph of the introduction and he is obviously the main character of the novel. He was a dog trader from Prague, who lived by selling bastard animals that he falsified the pedigrees of. Švejk was unmarried and spent a great deal of time in the pubs of the Bohemian capital.

Švejk possessed considerable oral skills, but his mental horizon is still under debate. It is known that he was dismissed from the army due to idiocy, but it is unclear if this was feigned or not. He certainly had a good memory and had read a lot, which indicates that his limited mental abilities may have been stage-play. In the epilogue to Part One the author explicitly states that he never meant Švejk to be feeble-minded, so that issue should be clear.

Politically, he was the apparently not very active, only brief passages reveal that he was hostile to Austria and the Catholic Church, although he mostly said exactly the opposite. Švejk was occasionally both deceitful and a thief, but in other cases he showed moral substance, particularly towards the end of the novel. He could at times appear detached and cynical - perhaps this was a defence mechanism in the unforgiving surroundings he found himself in.

Švejk came through the war unhurt, but what happened to him at the front is unclear as the novel was never completed. His first name Josef is first used in his confession at c.k. policejní ředitelství in the second chapter. In the course of the novel the main character is mentioned more than 2,000 times in a novel of slightly more than 200,000 words.

Personal information

The author provides little biographical information on his hero, but some details can be read or deduced from the novel.

Very early on the reader is told that the soldier suffers from rheumatism, and made a living by trading dogs. Later it is revealed that his father was Prokop Švejk and the mother Mrs. Antonie Švejková and the soldier seems to have been born in Dražov by Strakonice. At the outbreak of war he must have lived close to U kalicha in Praha II.. Through anecdotes we know that he some years back worked in Moravská Ostrava. Still many years back he was wandering/travelling around and got as far as Bremen. Furthermore he had once lived in Opatovická ulice. We know that he some time before and after 20 December 1914 served with Oberleutnant Lukáš in Prague. As a soldier he had served with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in Budějovice, and it was this regiment he rejoined some time after the outbreak of war, probably in early 1915. Švejk had also served as a conscript in Trient (Trento), and this city is a theme that appears in all the three versions of The Good Soldier Švejk (1911, 1917, 1921). That he was a soldier in Trento means that IR. 91 was not the only regiment he served with (this regiment was never garrisoned here).

The good soldier's age

At first sight it seems that Švejk's age at the outbreak of war was between 31 and 36 and he was a so called Landsturm-mann (reservist). This can be deduced from the circumstances around the draft at Střelecký ostrov and is also in line with Jaroslav Hašek's own entry into the army. This is however inconsistent with what he himself says in his anecdote about supák Schreiter where it is revealed that he served in the army in late 1912. He could thus at the earliest have started his military service in 1909, and would thus have been born between 1888 and 1891, leaving him aged from 24 to 27 in 1915.

Superarbitrated soldier on manoeuvres?

As the reader of The Good Soldier Švejk would know Švejk was years ago dismissed from the army due to idiocy, but then follows a logical short-circuit: he still took part in military exercises, and several of them: in Tábor, Písek, Velké Meziříčí, and Veszprém. His manoeuvres in South Bohemia may have been inspired by the experiences of Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj, the others rather inspired by news items picked up and memorised by the avid newspaper reader Hašek. That he took part in exercises in 1910 means that he at most could have been 32 that year, so he could not have been born before 1878.

Background

The figure of Švejk is in the end a product of the author's literary creativity, but as with several of the other characters in the plot he clearly has real-life models. The most obvious of these is the writer himself who lends several personal qualities and biographical details to his hero. See Jaroslav Hašek for more on this theme.

A borrowed name

The name Josef Švejk itself is by near certainty borrowed from a real person. A young man of that name is registered with home address next to U kalicha from June 1912, and may have lived there also when Jaroslav Hašek invented his good soldier in May 1911. It is quite likely that Jaroslav Hašek knew this man (or knew about him), particularly since both from 1916 both served in České legie. That said, circumsatnces dictate that he could hardly have borrowed more than the name from him.

Another Josef Švejk that the author surely knew about was the deputy Josef Švejk from the Agrarian Party. This person is much more likely to have lent the good soldier his name in 1911. The young Josef is however a good candidate for having sparked the rebirth of The Good Soldier Švejk in 1917 and not the least in 1921 (it is only now that Švejk is connected to U kalicha).

Offiser's servant Strašlipka

Another often touted inspiration is František Strašlipka, the servant of Oberleutnant Rudolf Lukas from the outbreak of war until the formers capture on 24 September 1915. Apart from his position in the nomenclature of IR. 91, Strašlipka is also likely to have inspired Švejk's incessant story-telling.

Otherwise Švejk's and Strašlipka's biographies differ greatly. Strašlipka was the Putzfleck of Rudolf Lukas from the very start of the war and joined him in the field immediately. Švejk for his part was originally a Landsturm reservist and to judge by his call-up date he was 10 years older than Strašlipka. He was drafted several months later and didn't serve only Oberleutnant Lukáš. Strašlipka was unlike Švejk never super-arbitrated and Švejk also served as a messenger, a role the former never had.

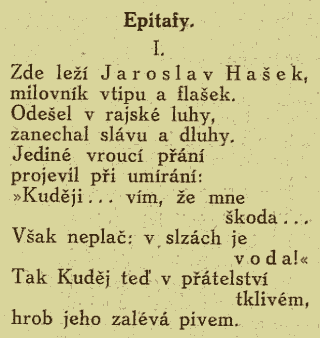

Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj

Last but not least some elements from the experiences of Hašek's good friend Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj (1881 - 1955) can be recognised in The Good Soldier Švejk. This is particularly evident in Part One where the plot is set in civilian life and few of the chapters have any obvious links to the author's own time-line during the early months of the war.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] Velká doba žádá velké lidi. Jsou nepoznaní hrdinové, skromní, bez slávy a historie Napoleona. Rozbor jejich povahy zastínil by slávu Alexandra Macedonského. Dnes můžete potkat v pražských ulicích ošumělého muže, který sám ani neví, co vlastně znamená v historii nové velké doby. Jde skromně svou cestou, neobtěžuje nikoho, a není též obtěžován žurnalisty, kteří by ho prosili o interview. Kdybyste se ho otázali, jak se jmenuje, odpověděl by vám prostince a skromně: „Já jsem Švejk…“

Credit: Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Šerák, Jan Morávek, Jan Prchal

Literature

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl I., ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl II., ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války. Díl III., ,1922

- Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk während des Weltkrieges, ,1926

- Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk während des Weltkrieges, ,1926

- Švejk, egy derék katona kalandjai a világháborúban,

- Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, ,1911 (banned), 1912 (re-issued)

- Dobrý voják Švejk, ,8.7.1911

- Dobrý voják Švejk, ,12.9.1911

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917

- Hledání Josefa Švejka v archivech,

- The Good Soldier Švejk (novel), Maciej Górny,7.10.2015

- Divadélko Adria, ,1.11.1921

- Prager Lokalstücke, B.,5.11.1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, Ivan Olbracht,15.11.1921

- Švejk, DRAF,18.11.1921

- Kapitola literárně-kominická, Karel Vaněk,18.11.1922

- "Le Brave Soldat Chvéïk" de Jaroslav Hasek, ,16.4.1932

- Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein., ,5.1.1923

- „Švejk" pokládán za nemravný spis v Německu, ,19.1.1928

- Velký úspěch "Dobrého vojáka Sveika" v Berlíně", ,24.1.1928

- Hrdina Švejk, Viktor Dyk,15.4.1928

- "Švejk“ a senátor Dyk, -,24.4.1928 Masaryk

- Švejkoviny, ,25.4.1928

- Od Švejka - k Masarykovi, J.,27.4.1928

- Švejk a čeští socialiste, ,5.5.1928

- Dyk proti Švejkovi — klerikálové proti legionářům, ,7.5.1928

- Theaternachrichten, ,22.11.1928

- Hrdinové z dobrého vojáka Švejka se sešli, ,30.10.1932

- Ein Verein der "Freunde des guten Soldat Schweijk", ,9.11.1932

- Jubilejní vydání Švejka, ,26.4.1936

- Haškův Švejk zdrojem inspirace, ,14.7.1948

- Díl I., ,1.9.1924

- Díl II., ,2.9.1924

- Díl III., ,3.9.1924

- Díl IV., ,4.9.1924

- Díl V., ,6.9.1924

- Díl VI., ,10.9.1924

- Díl VII., ,12.9.1924

- Díl VIII., ,13.9.1924

- Díl IX., ,15.9.1924

- Díl X., ,18.9.1924

- Díl XI., ,20.9.1924

- Díl XII., ,22.9.1924

- Díl XIII., ,25.9.1924

- Díl XIV., ,27.9.1924

- Díl XV., ,1.10.1924

- Díl XVI., ,4.10.1924

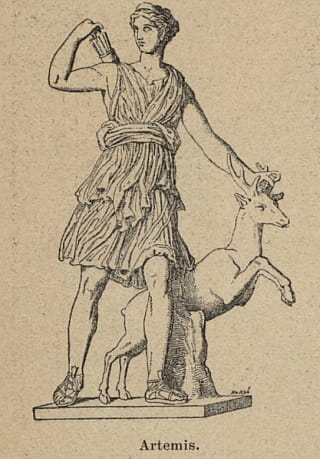

| Artemis |  | |||

| |||||

,1908

Artemis is mentioned indirectly by the author through the expression "the temple of the goddess in Ephesus". See Temple of Artemis.

Background

Artemis was a Greek goddess, daughter of Zeus and sister of Apollo. Artemis was the virgin moon goddess for hunting, healing, chastity and child birth. She was also protector of wild animals and the wilderness. She was often revered as a goddess of fertility. Her Roman equivalent was Diana.

Her named had already appeared directly in an article by Jaroslav Hašek in Čechoslovan on 29 January 1917, but in the Roman version of Diana.

Když se zametá

A náš redaktor chtěl se dostat do dějin. Stejně jako Hérostratés, když zapálil chrám bohyně Diany, právě v tu noc, kdy se narodil Alexandr Veliký. Jenže Hérostratos měl před ním tu výhodu, že nebyl osobní.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] Mám velice rád tohoto dobrého vojáka Švejka, a podávaje jeho osudy za světové války, jsem přesvědčen, že vy všichni budete sympatizovat s tím skromným, nepoznaným hrdinou. On nezapálil chrám bohyně v Efesu, jako to udělal ten hlupák Herostrates, aby se dostal do novin a školních čítanek.

Credit: wikipedia.no

Also written:Ἄρτεμιςgr

| Herostratus |  | |||

| |||||

© GreeceHighDefinition

Herostratus is ridiculed as being exactly the opposite of the unassuming hero of this novel. Herostratus is described as the fool who set fire to the temple in Ephesus in order to get his name in newspapers and text books.

Background

Herostratus (also called Herostrates) set fire to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus in 356 BC in order to become known, cf Herostratic fame. He was executed the same year.

This was not the first time Jaroslav Hašek wrote about Herostratus. In a stinging article in Čechoslovan on 29 January 1917 a similar imagery appears. The target is easy to identify although no names are mentioned: Bohdan Pavlů, editor of the competing weekly Čechoslovák in Petrograd.

Sergey Soloukh (2017) also points out the parallel to the story Cena slávy from 1913. The author mixes up the name with Efialtes but it is without doubt Herostrates, Ephesus and the temple of the goddess Diana he has in mind.

Když se zametá

A náš redaktor chtěl se dostat do dějin. Stejně jako Hérostratés, když zapálil chrám bohyně Diany, právě v tu noc, kdy se narodil Alexandr Veliký. Jenže Hérostratos měl před ním tu výhodu, že nebyl osobní.

Cena slavý

Ve starověku žil v Řecku muž jménem Efialtes, jehož jedinou tužbou bylo, aby se stal slavným a aby se o něm mluvilo. Aby toho dosáhl, šel a zapálil nádherný chrám bohyně Diany v Efesu, jeden ze sedmi divů světa.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] Mám velice rád tohoto dobrého vojáka Švejka, a podávaje jeho osudy za světové války, jsem přesvědčen, že vy všichni budete sympatizovat s tím skromným, nepoznaným hrdinou. On nezapálil chrám bohyně v Efesu, jako to udělal ten hlupák Herostrates, aby se dostal do novin a školních čítanek.

Also written:HerostratesHašekHerostratoscz

Literature

- Když se zametá ..., Jaroslav Hašek,29.1.1917J

- Cena slavý, Jaroslav Hašek,8.1.1913

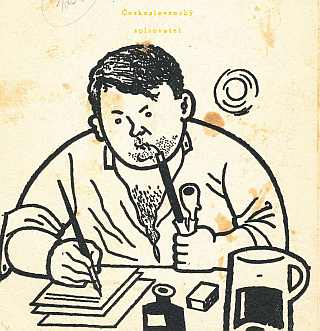

| Hašek, Jaroslav Matěj František |  | |||

| *30.4.1883 Praha - †3.1.1923 Lipnice nad Sázavou | |||||

| |||||

O životě Jaroslava Haška, , 1953

,10.9.1914

Hašek refers to himself at least eight times in The Good Soldier Švejk. He signs the introduction as "The author". Then he briefly appears as "I" in the narrative in [I.6] when he mentions the police archives and their records of detective Bretschneider's dog purchases. In [I.9] he uses he first person plural when introducing the garrison prison and in [I.14] he re-tells his experiences with officer servants. Finally he signs the epilogue to Part I, and for the only time he uses his full name.

Background

Hašek was a Czech writer, best known for the unfinished satirical novel The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk During the World War. He wrote around 1,500 short stories, six collections of short stories, was the co-author of a poetry book, and also contributed to some plays and cabarets. Jaroslav Hašek is considered a prominent satirist, and The Good Soldier Švejk, being translated into 54 languages[a] (59 if variations are counted)[1], is probably the most translated book written in Czech ever.

The Good Soldier Švejk closely mirrors the author's own experiences in k.u.k. Heer in 1915, and he also includes many autobiographical elements from other periods in his life. For more information on the connection between the novel and his author, see Jaroslav Hašek in the 'Who is Who' section.

Quote(s) from the novel

[Úvod] On nezapálil chrám bohyně v Efesu, jako to udělal ten hlupák Herostrates, aby se dostal do novin a školních čítanek. A to stačí. Autor

[I.6] Nevím, jestli ti pánové, kteří po převratu prohlíželi policejní archiv, rozšifrovali položky tajného fondu státní policie, kde stálo: B...40 K, F...50 K, L...80 K atd., ale rozhodně se mýlili, že B, F, L jsou začáteční písmena nějakých pánů, kteří za 40, 50, 80 atd. korun prodávali český národ černožlutému orlu.

[I.9] Posledním útočištěm lidí, kteří nechtěli jít do války, byl garnison. Znal jsem jednoho suplenta, který nechtěl střílet jako matematik u artilerie a kvůli tomu ukradl hodinky jednomu nadporučíkovi, aby se dostal na garnison.

[I.11.1] Pamatuji se, že nám jednou při takové polní mši nepřátelský aeroplán pustil bombu právě do polního oltáře a z polního kuráta nezbylo nic, než nějaké krvavé hadry.

[I.14.2] U 91. pluku znal jsem jich několik. Jeden pucflek dostal velkou stříbrnou proto, že uměl báječně péct husy, které kradl...

[I.14.2] Viděl jsem jednoho zajatého důstojnického sluhu, který od Dubna šel s druhými pěšky až do Dárnice za Kyjevem...

[I.14.2] Nikdy nezapomenu toho člověka, který se tak mořil s tím přes celou Ukrajinu...

[I.16] Stane-li se však slovo Švejk novou nadávkou v květnatém věnci spílání, musím se spokojit s tímto obohacením českého jazyka. Jaroslav Hašek.

Also written:Ярослав ГашекruЯрослав Гашекua

| 1. | The number 54 also includes translations that are partial, e.g. Latin and Irish. Not included are language variants: English(2), Spanish(3), Portuguese(2) and German(2). If these are counted the number is 59. |

Literature

- Překlady Osudů do jednotlivých jazyků, ,2020 [a]

- Jaroslav Hašek,

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války I, ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války II, ,1921

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války III, ,1922

- Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk während des Weltkrieges I, ,1926

- Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky, ,1911/1912

- Trampoty pana Tenkráta, ,1912

- Průvodčí cizinců a jiné satiry z cest i domova, ,1913

- Můj obchod se psy a jiné humoresky, ,1915

- Pepíček Nový a jiné povídky, ,1921

- Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein., ,5.1.1923

| a | Překlady Osudů do jednotlivých jazyků | 2020 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

Introduction | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |