Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others. This are still listed as fictional because they are literary creations that are only partly inspired by their like-sounding "models".

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are provided as tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

3. Švejk before the court physicians | |||

| Mr. Demartini |  | ||||

| ||||||

Demartini was the fat head of the guards for the prisoners in custody at the c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

Background

The chief prison guard has perhaps been inspired by the very real police high commisioner in Prague, Rudolf Demartini (1866-1919), who lived in Vinohrady (1906). This is a person Jaroslav Hašek surely knew or knew about. Little is known about him except for that he had three daughters and is buried at Olšany in Žižkov.

It has not been confirmed if he really was the chief guard in the remand arrest at c.k. zemský co trestní soud in 1914. He is not listed as an employee of the criminal court in the address books of 1907 and 1912 and it seems strange that someone with such a high rank is employed as the head of the prison guards. Therefore this is probably a borrowed name and not much more.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Čisté, útulné pokojíky zemského „co trestního soudu“ učinily na Švejka nejpříznivější dojem. Vybílené stěny, černě natřené mříže i tlustý pan Demartini, vrchní dozorce ve vyšetřovací vazbě s fialovými výložky i obrubou na erární čepici. Fialová barva je předepsána nejen zde, nýbrž i při náboženských obřadech na Popeleční středu i Veliký pátek.

Literature

- Demartini a demartinka,

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních (1907),

- Změna jména, ,16.7.1915

- Úmrtí, ,25.4.1909

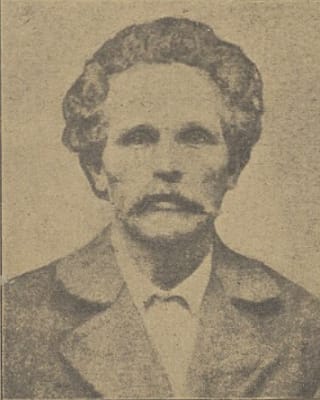

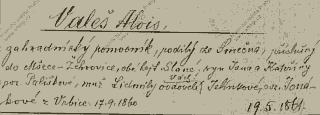

| Murderer Valeš, Alois |  | ||||

| *19.5.1861 Mšecké Žehrovice - †18.12.1908 Nusle (Pankrác) | ||||||

| ||||||

Krvavá tragedie v Krči, ,1904

© AHMP

,20.12.1908

Valeš was a well knwn murderer who some years earlier had been interrogated by the same good-natured man who questioned Švejk at c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

Background

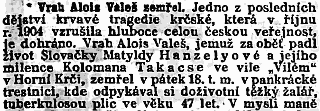

Valeš and his wife Ludmila committed a brutal double murder in April 1902 in the villa "Vilém" in Horní Krč where he was employed as a gardener. The victims were the young Slovak/Hungarian couple Matilda Hanzely and József Takács. They were planning to emigrate to America and therefore had a lot of money at hand. murderer Valeš hid the corpses in the garden and the crime was not discovered until October 1904. In February 1905 the couple was sentenced to death but the term was converted to life imprisonment by Emperor Franz Joseph I..

Interrogation

Amongst those who interrogated murderer Valeš in 1905 were Karel Křikava and Václav Olič. They were police officers that Jaroslav Hašek knew and one of them may well have served as models for the good-natured interrogator. Egon Erwin Kisch mentions the Valeš-case briefly in the story Polizeimuseum, where he reveals that the murderer's weapon is on exhibition.

The villa owner

At the time of the discovery of the murder the owner of the villa was Alois Bauer, a merchant who lived in Smíchov. When the trial took place (January 1905) he was under administration and the villa was sold. In 1909 Bauer committed suicide by jumping into the Vltava near Střelecký ostrov [a].

E.E. Kisch: Polizeimuseum

Eine ganze Vitrine weist die Instrumente auf, mit denen das wurdige Ehepaar Valeš zu Krtsch das Liebespaar Takasz-Hanzely im Schlafe umgebracht hatte: ein Jagdgewehr, ein Strick, ein Revolver, ein Beil.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Starší pán dobromyslného vzezření, který kdysi, vyšetřuje známého vraha Valeše, nikdy neopomenul jemu říci: „Račte si sednout, pane Valeš, právě je zde jedna prázdná židle.“

Credit: Milan Hodík, Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

- Konec majitele villy, ,25.4.1909 [a]

- Krvavá tragedie v Krči, ,1904

- Matrika zemřelých,

- Der Doppelmord in Krtsch, ,9.11.1904

- Zločin, či mystifikace?, ,9.11.1904

- Záhadný dvojnásobný zločin, ,30.1.1905

- Leden, 30.,

- Vrah Alois Valeš zemřel, ,20.12.1908

- Die Börse der Nachrichten, Egon Erwin Kisch,6.12.1925

| a | Konec majitele villy | 25.4.1909 |

| Pontius Pilate |  | |||

| *? - †? | |||||

| |||||

Pontius Pilate is written about by the author when he describes those of the examining magistrates who were most obsessed with the letter of the law as "the Pilates of the new era".

Background

Pontius Pilate was Roman prefect of Judea in the period 26 to 36 AD and oviously plays a central part in the Bible as the Roman official who sentenced Jesus to death by crucifixion.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Vracela se slavná historie římského panství nad Jerusalemem. Vězně vyváděli i představovali je před Piláty roku 1914tého dolů do přízemku. A vyšetřující soudcové, Piláti nové doby, místo aby si čestně myli ruce, posílali si pro papriku a plzeňské pivo k Teissigovi a odevzdávali nové a nové žaloby na státní návladnictví.

Also written:Pilát Pontskýcz

| Prokop Švejk |  | |||

| |||||

Prokop Švejk is here at c.k. zemský co trestní soud mentioned in passing by Švejk when referring to his parents. They are mentioned again in [II.5], and it is only then their full names are revealed and it transpires that they are from Dražov.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] „Já myslím,“ odpověděl Švejk, „že jím musím být, poněvadž i můj tatínek byl Švejk a maminka paní Švejková. Já jim nemohu udělat takovou hanbu, abych zapíral svoje jméno.“

[II.5] Jakmile jsem ho poznal, šel jsem k němu na plošinu a dal jsem se s ním do hovoru, že jsme oba z Dražova. On se ale na mne rozkřik, abych ho neobtěžoval, že prý mne nezná. Já jsem mu to začal vysvětlovat, aby se jen upamatoval, že jsem jako malej hoch k němu chodil s matkou, která se jmenovala Antonie, otec že se jmenoval Prokop a byl šafářem. Ani potom nechtěl nic vědět o tom, že se známe. Tak jsem mu ještě řekl bližší podrobnosti, že v Dražově byli dva Novotní, Tonda a Josef.

| Mrs. Antonie Švejková |  | |||

| |||||

Antonie Švejková is mentioned in passing by Švejk when referring to his parents in a conversation at c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

The parents are mentioned again in [II.5], and it is only then that their full names are revealed and it transpires that they are from Dražov.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] „Já myslím,“ odpověděl Švejk, „že jím musím být, poněvadž i můj tatínek byl Švejk a maminka paní Švejková. Já jim nemohu udělat takovou hanbu, abych zapíral svoje jméno.“

[II.5] Jakmile jsem ho poznal, šel jsem k němu na plošinu a dal jsem se s ním do hovoru, že jsme oba z Dražova. On se ale na mne rozkřik, abych ho neobtěžoval, že prý mne nezná. Já jsem mu to začal vysvětlovat, aby se jen upamatoval, že jsem jako malej hoch k němu chodil s matkou, která se jmenovala Antonie, otec že se jmenoval Prokop a byl šafářem.

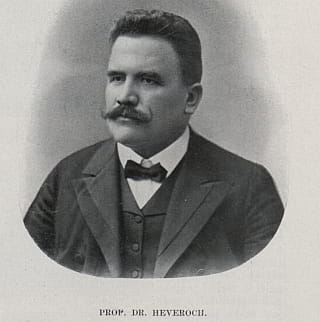

| Doctor Heveroch, Antonín |  | ||||

| *29.1.1869 Minice - †2.3.1927 Praha | ||||||

| ||||||

,28.5.1909

Heveroch was mentioned in a story by one of Švejk's fellow detainees who had gone to a lecture by Heveroch to learn to fake madness. He drank from the ink pot and performed his bodily needs in front of the legal commission. The only mistake he made was to bite a psychiatrist in the right foot, a procedure that was not described by Heveroch. One of the doctors of the commission that examined Švejk was a follower of Heveroch's psychiatric teaching.

Background

Heveroch was a notable Czech psychiatrist and neurologist who was, amongst other things, known for his studies on dyslexia and epilepsy. His book On Freaks and Striking People[a] was according to František Langer amongsts Jaroslav Hašek's favourites.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] „Já těm soudním lékařům nic nevěřím,“ poznamenal muž inteligentního vzezření. „Když jsem jednou padělal směnky, pro všechen případ chodil jsem na přednášky k doktoru Heverochovi, a když mě chytili, simuloval jsem paralytika právě tak, jak ho vyličoval pan doktor Heveroch.

Literature

- O podivínech a lidech nápadných, ,1901 [a]

| a | O podivínech a lidech nápadných | 1901 |

| Rittmeister Rotter, Theodor Franz Adalbert |  | ||||

| *28.3.1873 Krumlov - †1944 ? | ||||||

| ||||||

Rotter in the middle.

,15.9.1909

Za císáře pána, Michal Dlouhý

,1910

Rotter is mentioned 4 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Rotter was a well known police chief in Kladno who trained his dogs by experimenting with them on tramps in the district. This is according to a story Švejk tells his fellow prisoners at c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

The policeman is mentioned again in [II.2] during Švejk's wanderings around Písek. This story is almost identical, but is now told by a tramp.

Background

Rotter was a renowned dog breeder and policeman, stationed in Kladno in 1909 and 1910. During his period of service here he became the first ever to introduce police dogs in k.k. Gendarmerie.

Career

Rotter was born in 1873 in Krumlov with Heimatrecht Budějovice [a], son of brew-master Theodor Rotter and Rosalie. In his younger years he served as an active (professional) officer in k.u.k. Heer, first as a cadet in Infanterieregiment Nr. 11 (Písek) from 1 September 1893 until 1895[d]. He was then promoted to Leutnant on 1 May 1895 and this year he was also transferred to Infanterieregiment Nr. 56 (Kraków). In 1901 he left the army and continued his career in k.k. Gendarmerie [f].

Trutnov, Chomutov, Kladno

He carried the rank lieutenant into the police and was promoted to Oberleutnant on 1 November 1902. First he led the gendarmerie in Trutnov until 1906 when he was posted to Chomutov. In 1909 he was subsequently transferred to Kladno where he 1 November 1909 was promoted to Rittmeister. It was during his term in Kladno that his name was first noticed in connection with police dogs [g] and he was at time mentioned in the newspapers several times.

Písek

His stay in Kladno was brief because already in 1910 his career path continued to Písek where he became commander of Gendarmerieabteilungskommando Nr. 14, an assignment that continued at least until 1916. The census records reveal that he was registered on 16 August 1910, lived at the department station in Pražská ulice č.p. 261 with his wife Hedwiga and 5 year old son Franz[j]. Here they had a flat at their disposal where also a servant and a female cook lived. He reported Czech as his mother tongue whereas his wife and his son reported German. In 1911 Rotter published the booklet Anleitung zur Dressur von Polizeihunden. Towards the end of the war he was stationed in Djakova in occupied Montenegro as Bezirkskommandant. He was promoted to Oberstleutnant on 1 August 1918[e].

Hašek and Rotter

,1.11.1909

In 1908 Rotter went to Saarbrücken to attend a course in training police dogs. Back home he on his own initiative bought two German Shepherds from Fuchsův psinec. He trained the dogs Vlk and Vlčka for service purposes and in Svět zvířat appeared a picture of the latter "catching" a runaway. The magazine also printed a couple of photos with Rotter present, and in 1910 he even wrote some articles for them, signed T. R.. At this time Hašek was editor at the magazine so it goes without saying that the two knew each other.

Hašek seems to have kept in touch with Rotter because Josef Lada wrote that he and Hašek on 28 June 1914 visited Rotter in Kladno[b]. This does however seem strange, considering that Rotter had moved to Písek already in 1910.

Czechoslovakia

Rotter continued in the police in Czechoslovakia after the war and newspaper articles reveal that he was promoted to plukovník (colonel) and was still considered a prominent dog expert. Otherwise it is not known where he lived. In 1939 it was revealed that he had retired[h], he was by now 67.

In his advanced years he wrote several books on dog breeding, the latest of which was published in 1938.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Taky vám dám příklad, jak se na Kladně zmejlil jeden policejní pes, vlčák toho známého rytmistra Rottera. Rytmistr Rotter pěstoval ty psy a dělal pokusy s vandráky, až se Kladensku počali všichni vandráci vyhejbat.

[II.2] "....Jó, dneska mají právo četníci." "Voní ho měli i dřív," ozval se vandrák, "já pamatuju, že na Kladně bejval četnickým rytmistrem nějakej pan Rotter. Von vám najednou začal pěstovat tyhlety, jak jim říkají, policejní psy tý vlčí povahy, že všechno vyslídějí, když jsou vyučení. A měl ten pan rytmistr na Kladně těch svejch psích učeníků plnou prdel...."

Credit: Petr Netopil, Josef Lada, Michal Dlouhý, Radko Pytlík

Literature

- Toulavé house, ,1971 [b]

- Kladenský rytmistr, [i]

- Matrika, [a]

- Sčitání lidu 1910, [j]

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 349), ,1894 [d]

- Schematismus der k.k. Landwehr (s. 548), ,1911 [c]

- Verordnungsblatt für die kaiserlich-königliche Gendarmerie, ,26.10.1901 [f]

- Verordnungsblatt für die kaiserlich-königliche Gendarmerie, ,27.10.1909

- Verordnungsblatt für die kaiserlich-königliche Landwehr, ,8.5.1916

- Verordnungsblatt für die kaiserlich-königliche Landwehr, ,13.8.1918 [e]

- Polizeihunde für die Gendarmerie in Böhmen, ,18.8.1909 [g]

- Předvádení prvnich četnických psů na policejním ředitelství v Praze, ,1.11.1909

- Produkce policejních psů, ,20.11.1909

- Die ersten österreichischen Gendarmeriehunde, ,13.1.1910

- Der leuchtende Polizeihund, ,14.1.1910

- Policjeni pes, ,21.10.1910

- Eine Polizeihunde-Vorführung vor dem Thronfolger, ,7.12.1910

- Zajímavá produkce s policejními a sanitními psy, ,28.10.1916

- Für je tausende gefangene Italiener..., ,4.11.1917

- Pes přítel člověka, ,20.3.1931

- Ministr vnitra generál Josef Ježek v jižních Čechách., ,5.8.1939 [h]

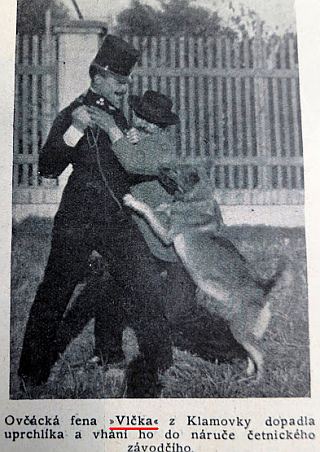

| Vlčka |  | |||

| |||||

,1.11.1909

Vlčka was most probably the name of the police dog that is mentioned in connection with Rittmeister Rotter's experiments in Kladno where he lets police dogs chase tramps. In the novel the dog is referred to as a police dog and wolf-dog.

Background

Vlčka was a female police dog that Rittmeister Rotter brought bought from Fuchsův psinec together with the male Vlk in 1909. It was probably one of those dogs Švejk had in mind when he told his anecdote. The author knew Rotter well and had surely been aware of and seen both dogs.

Vlčka was moreover bred at the kennel of Fuchs a Klamovka, next to the villa where Svět zvířat had their editorial offices and where Jaroslav Hašek worked as an editor. He would therefore have known the female dog well and in an article in the magazine 1 November 1909 it is stated that her training took place here at Klamovka[a].

On 16 October 1909 Rittmeister Rotter showed off the skills of Vlčka and a Doberman Pinscher called Petar on the premises of c.k. policejní ředitelství. The whole leadership of police HQ was present, amongst them Polizeikommissar Drašner and Ladislav Adamička (the brother of Josef Adamička). The article also states that Vlčka was bought from the kennel at Klamovka earlier in the year.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Taky vám dám příklad, jak se na Kladně zmejlil jeden policejní pes, vlčák toho známého rytmistra Rottera. Rytmistr Rotter pěstoval ty psy a dělal pokusy s vandráky, až se Kladensku počali všichni vandráci vyhejbat.

Credit: Petr Netopil, Michal Dlouhý

Literature

- Předvádení prvnich četnických psů na policejním ředitelství v Praze, ,1.11.1909 [a]

- Die ersten österreichischen Gendarmeriehunde, ,13.1.1910

- Dějiny služební kynologie,

| a | Předvádení prvnich četnických psů na policejním ředitelství v Praze | 1.11.1909 |

| Doctor Kallerson |  | ||||

| ||||||

Hůla is of the opinion that Hašek invented the names Kallerson and Weiking

Kallerson is mentioned together with the psychiatrists Doctor Heveroch and Doctor Weiking as someone who had founded a school within the discipline.

Background

Kallerson was according to The Good Soldier Švejk a psychiatrist but there is no information available apart from what is stated in the novel. Břetislav Hůla assumed that the name is an invention as he was unable to verify the existence of any well known psychiatrist Kallerson.

If the psychiatrist isn't invented it is probably a case of a distorted name. In one of Hašek's stories a Karl Larsson features, a name that is phonetically similar. This person was however not a psychiatrist, he was head of the Czechoslovak Salvation Army[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Věc byla úplně jasnou. Spontánním projevem Švejkovým odpadla celá řada otázek a zůstaly jen některé nejdůležitější, aby s odpovědí potvrzeno bylo prvé mínění o Švejkovi na základě systému doktora psychiatrie Kallersona, doktora Heverocha i Angličana Weikinga.

Literature

- Zápas z Armádou spasy, ,1921 [a]

| a | Zápas z Armádou spasy | 1921 |

| Doctor Weiking |  | ||||

| ||||||

Hůla is of the opinion that Hašek invented the names Kallerson and Weiking

Weiking is an Englishman mentioned together with the psychiatrists Doctor Heveroch and Doctor Kallerson. He had allegedly founded a certain school within the discipline of psychiatry.

Background

Weiking is supposed to have been an English psychiatrist but there is no information available apart from what is stated in The Good Soldier Švejk. The name doesn't sound partucularly English. Břetislav Hůla assumes that the names Doctor Kallerson and Weiking are inventions. Alternatively it is a distortion of the name of a real psychologist.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.3] Věc byla úplně jasnou. Spontánním projevem Švejkovým odpadla celá řada otázek a zůstaly jen některé nejdůležitější, aby s odpovědí potvrzeno bylo prvé mínění o Švejkovi na základě systému doktora psychiatrie Kallersona, doktora Heverocha i Angličana Weikinga.

|

I. In the rear |

| |

3. Švejk before the court physicians | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |