Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others. This are still listed as fictional because they are literary creations that are only partly inspired by their like-sounding "models".

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are provided as tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (588)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (45) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

III. The famous thrashing |

| |

1. Across Magyaria | |||

| Feldoberkurat Ibl |  | |||

| |||||

Der Soldatenfreund. 1915 Kalender

The real Feldkurat in der reserve Eybl serving field mass in Podmonasterz (ukr. Підмонасти́р) in Galicia 28 June 1915. Around this time his literary counterpart Feldoberkurat Ibl served his own mass for Švejk's departing march battalion in Királyhida.

© SOkA Beroun

Ibl was the chief field chaplain who performed the field mass in Királyhida for three departing march battalions. One of these headed for Russia, two for Serbia. His sermon didn't impress Švejk who on the train relays the mass and condemns it as idiocy squared. Ibl built the mass around a conversation between the mortally wounded veteran Fahnenführer Hrt and marshal Marschall Radetzky, set during the battle of Custoza.

It is also revealed that Ibl travelled on to Vienna where he repeated his sermon.

The field chaplain's speech was according to the author picked from a military calendar and this is no doubt true. Most of the content of the sermon is from Der Soldatenfreund calendar from 1915, page 72 and 73. See also Kriegskalender.

Background

or at least the name was inspired by Feldkurat Jan Eybl, a military cleric who served in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 together with Jaroslav Hašek for most of the time from 11 July until 24 September 1915. During this period Eybl celebrated at least three field masses that Hašek would normally have attended.

Still it can hardly me more than the name that associates him with the literary Ibl. Eybl's rank was the lower Feldkurat in der Reserve and he served at the front the entire period the author stayed in Királyhida (June 1915).

In his advanced years Jan Eybl said that he never held a mass like the one described in the novel. Nor does it make sense that two march battalions headed for Serbia at the time Švejk was in Királyhida. During the spring and summer 1915 k.u.k. Heer didn't have troops on Serbian territory, they withdrew before Christmas 1914. It was only in October 1915 that fighting on the Balkan-front flared up again.

The figure in the novel may therefore have been inspired by another cleric, probably a person from k.u.k. Feldsuperioriat or a garrison in Vienna. These were assigned duties in the area around the capital and after Jan Eybl himself was transferred here in July 1918 he held a couple of masses in Bruck. It should noted that Ibl continued to Vienna after finishing in Bruck, indicating that he was based here and didn't belong to IR. 91 or the garrison in Bruck.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Milí vojáci,“ řečnil vrchní polní kurát Ibl, „tak tedy si myslete, že je rok osmačtyřicátý a že vítězstvím skončila bitva u Custozzy, kde po desetihodinovém úporném boji musil italský král Albert přenechati krvavé bojiště našemu otci vojínů, maršálkovi Radeckému, jenž v 84. roce svého života dobyl tak skvělého vítězství.

Credit: Milan Hodik, Karel Pichlík, Jan Eybl

| King Carlo Alberto |  | |||

| *2.10.1798 Torino - †28.7.1849 Porto | |||||

| |||||

Carlo Alberto is mentioned by Feldoberkurat Ibl in the field mass he serves for the departing march battalion in Királyhida.

Background

Carlo Alberto (corr. Carlo Alberto) was king of Piedmont from 1831 to 1849, the adversary of Marschall Radetzky at the battle of Custoza in 1848.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Milí vojáci,“ řečnil vrchní polní kurát Ibl, „tak tedy si myslete, že je rok osmačtyřicátý a že vítězstvím skončila bitva u Custozzy, kde po desetihodinovém úporném boji musil italský král Albert přenechati krvavé bojiště našemu otci vojínů, maršálkovi Radeckému, jenž v 84. roce svého života dobyl tak skvělého vítězství.

| Fahnenführer Hrt |  | |||

| |||||

Der Soldatenfreund. 1915 Kalender

Hrt was a standard-bearer which is featured in Feldoberkurat Ibl's field mass, a mortally wounded hero at the battle of Custoza. He had taken part in battles as early as the Napoleonic Wars, at Aspern and Leipzig. The author indicates that Ibl's speach sounds as if taken from a Kalender. Švejk is here unusually fortright in his verdict; he refers to the field mass as "idiocy squared".

Background

Hrt and his story is exactly what the author says. It mainly picked from Der Soldatenfreund, 1915 calendar, page 72 and 73. Here the hero is called Fahnenführer Veit, cz. Vít, one of some minor discrepancies. It must be assumed that the author had the Czech version at hand when he wrote Feldoberkurat Ibl's speech. The kalendar was published in several of the languages of Austria-Hungary.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] S roztříštěnými údy na poli cti pociťoval zraněný praporečník Hrt, jak na něho hledí maršálek Radecký. Hodný zraněný praporečník ještě svíral v tuhnoucí pravici zlatou medalii v křečovitém nadšení.

| Archduke Joseph Ferdinand |  | |||

| *24.5.1872 Salzburg - †25.8.1942 Wien | |||||

| |||||

Unsere Offiziere, , 1915

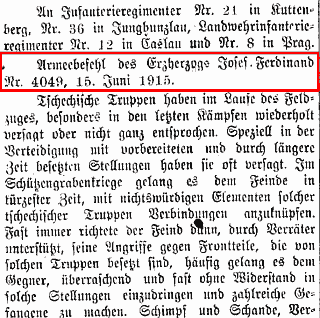

Extract from Joseph Ferdinand's allaged order.

,5.12.1917

Czech version.

,2.10.1915

News about the confiscation of flyers claiming to be Joseph Ferdinand's and Friedrich's army orders.

,18.8.1915

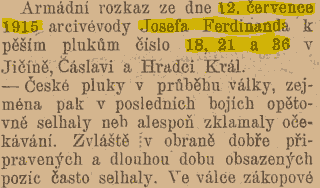

Joseph Ferdinand is mentioned when Švejk's march battalion was read aloud two army orders before they entered the train that took them to the front. The orders were prompted by an incident where two entire battalions (with officers) from Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 went over to the Russians by Dukla on 3 April 1915. The mass defection is said to have taken place to the tunes of the regiment's orchestra.

The first order was signed by Emperor Franz Joseph I. on 17 April 1915. It stated that the regiment was dissolved forever and the standard moved to the War Museum in Vienna. The second order was signed by Joseph Ferdinand, but not dated. It dealt with the unreliability of Czech troops, used threatening language and was to be read aloud to all Czech regiments. The order confirms that Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 was dissolved.

Background

Joseph Ferdinand was an archduke of the House of Habsburg (the Tuscan branch) and a military commander. In 1915 he was commander-in-chief of the 4th army but was replaced due to the disastrous losses during the Brussilov offensive in 1916. After the war, he was allowed to live in Austria but had to give up his rights as a noble. He was arrested by the Nazis in 1938 and spent a short time in Dachau.

Joseph Ferdinand's order

The order reproduced in The Good Soldier Švejk is nearly identical to one that was printed in the Czech exile press during the war[d]. Roughly the same wording also appears in an interpellation by German nationalists in Reichsrat[b]. These two are the only copies that we know were printed during the war but after 1918 several more were to follow. In Vienna's Kriegsarchiv several versions of it can be found, also in Hungarian. From the correspondence between AOK, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium and Kriegsüberwachungsamt it is clear that it was a fake.

Leaflets

Due to censorship the text was not announced in the newspaper or made public at all. Traces of the order is however found i a statement from the district court in Liberec, dated 2 August 1915. A non-periodical print titled Armeebefehl des Erzherzog Josef Ferdinand, without information about publisher, printer and place of publication, was to be confiscated[a]. The same verdict was announced by other courts in Bohemia.

In the Czech exile press

Later in the autumn a complete text was printed in the Czech exile press, and with additional comments[d]. The text was allegedly distributed in large quantities as leaflets by mail in North Bohemia and in Vienna, and was allegedly a fake designed to stain the Czech population. The originator was said to be a skirt-maker from Ústí nad Labem who was duly arrested and imprisoned in Terezín. The order is dated 12 July 1915 and addresses Infanterieregiment Nr. 18, Infanterieregiment Nr. 21 and Infanterieregiment Nr. 36.

Kriegsministerium

A letter from k.u.k. Kriegsministerium dated 27 October 1915 reveals more about the origin of the order. Such on order had indeed been issued by some higher army commander whose name is not mentioned. It was concluded that further legal actions to stop the spread of the leaflets would be suspended because the contents of the order "quite accurately reflected the actual state of affairs". Otherwise, the last four sentences of the text on the leaflets had been added to the original order.

Parliament, 1917

According to the protocols from Reichsrat on 5 December 1917 Joseph Ferdinand's Armeebefehl was numbered 4049 and dated 15 June 1915. It regarded Infanterieregiment Nr. 21 from Čáslav, Infanterieregiment Nr. 36 from Mladá Boleslav, k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 12 from Čáslav and k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 from Prague[b]. IR 36 in particular was regarded as suspect and during the battle by Sienawa on 27 May 1915 more than 1,000 soldiers from the regiment were captured despite being well dug in. The regiment was on 16 July 1915 temporarily dissolved by imperial decree and was (as opposed to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28) never reconstituted.

General Matuschka

In 1919 the two orders that we know from The Good Soldier Švejk appeared in a Vienna newspaper. Here Joseph Ferdinand is not mentioned at all. According to the newspaper's source the order was issued at 27 June 1915 by Militärkommando Krakau who at the time had relocated to Moravská Ostrava. The order carried Reservatnummer 5654 and the content was very similar to Hašek's version. In addition it was decreed that Sokol-associations should be kept an eye on. The order was signed by General Matuschka. The source of the text is not known but was according to the newspaper a high-ranking officer[c].

General Ludwig Matuschka (1859-1942) was the commander of 1. Korpskommando and known for his hard-line stance on those he regarded as traitors. He signed the first death sentences of Czech civilians alreday at the end of 1914 and editor Kotek was the best known victim of the general's reign of terror.

Later versions

After the war the text appeared in various papers with more or less the same content. There are however inconsistencies inasmuch as the dates of issue rarely correspond and that the regiments that were addressed were not always the same. In one Austrain newspaper it was even claimed that it was Archduke Friedrich who issued the order[e].

Faked or authentic?

The diverging dates and signatures suggests that at least part of the alleged army order was faked. Worthwhile is also an analysis of the language. In the first part the tone is matter-of-fact and bureaucratic and is a sober description of the state of affairs during the spring of 1915. The last part is however emotional and threatening, a stark contrast to the first part. This fits well with the above-mentioned information from k.u.k. Kriegsministerium in 1915 that the last four paragraphs were not part of the original order. Therefore the text as reproduced in The Good Soldier Švejk and other printed material seems to be a distorted Armeebefehl, a parallel to the related order from Emperor Franz Joseph I. regarding Infanterieregiment Nr. 28. There is little doubt that some order along these lines was given, but by who? As opposed to the order to dissolve IR. 28 the original document has not been identified. Nor is it known who signed the order. Was it Joseph Ferdinand, Ludwig Matuschka or Archduke Friedrich?

In Hašek's word

Hašek's reproduction of both army orders is quite close to the text of the leaflets as quoted by the Czech exile press but it is not true that it concerned Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 or that Joseph Ferdinand was the head of the "Eastern Army". He commanded k.u.k 4. Armee, a unit that held a front section in Galicia and Russian Poland in the summer of 1915.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Potom Švejk počal mluvit o známých rozkazech, které jim byly přečteny před vstoupením do vlaku. Jeden byl armádní rozkaz podepsaný Františkem Josefem a druhý byl rozkaz arcivévody Josefa Ferdinanda, vrchního velitele východní armády a skupiny, kteréž oba týkaly se událostí na Dukelském průsmyku dne 3. dubna 1915, kdy přešly dva bataliony 28. pluku i s důstojníky k Rusům za zvuků plukovní kapely.

[III.1]Rozkaz arcivévody Josefa Ferdinanda:

České trupy během polního tažení zklamaly, zejména v posledních bojích. Zejména zklamaly při obraně posic, ve kterých se nalézaly po delší dobu v zákopech, čehož použil často nepřítel, aby navázal styky a spojení s ničemnými živly těchto trup. Obyčejně vždy směřovaly pak útoky nepřítele, podporovaného těmito zrádci, proti těm oddílům na frontě, které byly od takových trup obsazeny. Často podařilo se nepříteli překvapit naše části a takřka bez odporu proniknout do našich posic a zajmouti značný, velký počet obránců. Tisíckrát hanba, potupa i opovržení těmto bídákům bezectným, kteří dopustili se zrady císaře i říše a poskvrňují nejen čest slavných praporů naší slavné a statečné armády, nýbrž i čest té národnosti, ku které se hlásí. Dřív nebo později zastihne je kulka nebo provaz kata. Povinností každého jednotlivého českého vojáka, který má čest v těle, je, aby označil svému komandantovi takového ničemu, štváče a zrádce. Kdo tak neučiní, je sám takový zrádce a ničema. Tento rozkaz nechť je přečten všemu mužstvu u českých pluků. C. k. pluk čís. 28 nařízením našeho mocnáře jest již vyškrtnut z armády a všichni zajatí přeběhlíci z pluku splatí svou krví těžkou vinu.Arcivévoda Josef Ferdinand

Literature

- Erzherzog Joseph Ferdinand, ,2001 - 2016

- Kundmachungen, ,11.8.1915 [a]

- Das Verhalten der Tschechen im Weltkrieg, ,1918 [b]

- Beschlagnahme, ,17.8.1915

- Goldener Stern, ,21.8.1915

- Dokumenty, ,23.9.1915 [d]

- Das Verhalten des Tschechen im Kriege, ,10.5.1919 [c]

- Armeekommandobefehl, ,17.10.1927 [e]

- Dokumenty, ,8.1988

- Aus dem Tagebuch eines Kriegszivilisten, ,18.7.1930

- Bewunderingswürdige Staatstrue, ,12.7.1933

| a | Kundmachungen | 11.8.1915 | |

| b | Das Verhalten der Tschechen im Weltkrieg | 1918 | |

| c | Das Verhalten des Tschechen im Kriege | 10.5.1919 | |

| d | Dokumenty | 23.9.1915 | |

| e | Armeekommandobefehl | 17.10.1927 |

| Telephone operator Chodounský, Antonín |  | |||

| |||||

Chodounský is mentioned 46 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Chodounský is a telephone operator who is assigned to the 11th march company at the time of departure from Királyhida. He is part if the story to the very end, particularly on the train journey to Sanok where he shares the staff carriage with Švejk, Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek, Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk, cook Jurajda and Offiziersdiener Baloun.

It transpires that he has served at the Serbian front, and he mentions stopping in Osijek on the way there. In a conversation between Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in Budapest there is a hint that telephone operator Chodounský might be an informer. His first name "Tonouš" (nickname for Antonín) is revealed in Liskowiec when he writes two letters to his wife.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Na druhé straně vagonu proti Vaňkovi seděl kuchař okultista z důstojnické mináže a cosi psal. Za ním seděli sluha nadporučíka Lukáše vousatý obr Baloun a telefonista přidělený k 11. marškumpačce, Chodounský. Baloun přežvykoval kus komisárku a vykládal uděšeně telefonistovi Chodounskému, že za to nemůže, když v té tlačenici při nastupování do vlaku nemohl se dostat do štábního vagonu ku svému nadporučíkovi.

| Korporal Matějka |  | |||

| |||||

Matějka was a kaprál who overindulged in food on the way to the front in Serbia, this according to telephone operator Chodounský. This was at the very beginning of the war when food was plentiful and enthusiasm for the war was great. It happened on the way through Hungary down to the Balkans front by the river Drina.

Background

In Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 many Matějka served during the war. One of them was Adolf Matějka from Vimperk and he was in the regiment at the same time as Hašek and the two were even taken prisoner together at Chorupan 24 September 1915[a]. Two more Matějka from the regiment were captured the same day.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Po všech tratích jsme nic jiného nedělali, než blili z vagonů. Kaprál Matějka v našem vagoně se tak přecpal, že jsme museli dát mu přes břicho prkno a skákat po něm, jako když se šlape zelí, a to mu teprve ulevilo a šlo to z něho horem dolem. Když jsme jeli přes Uhry, tak nám házeli do vagonů na každé stanici pečené slepice.

Literature

- The battle of Chorupan, ,2021 [a]

| a | The battle of Chorupan | 2021 |

| Oberleutnant Macek |  | |||

| |||||

Macek was a Czech senior lieutenant who was killed in the fighting in Bosnia. It is telephone operator Chodounský who lectured about this on the train before Moson and adds that Macek spoke only German.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Přijel z druhého konce batalionskomandant a svolal všechny na poradu, a potom přišel náš obrlajtnant Macek, Čech jako poleno, ale mluvil jen německy, a povídá, bledý jako křída, že se dál nemůže ject, trať že je vyhozena do povětří v noci, Srbové že se dostali přes řeku a jsou nyní na levém křídle.

| Jurajdová, Helena |  | |||

| |||||

Jurajdová was the wife of the occultist cook Jurajda and she was now publishing a theosophic magazine. He is mentioned as the husband writes here a letter, ingeniously composed to pass censorship. Jurajda uses the name Helenka, diminutive of Helena.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Věř mně, drahá Helenko, že se opravdu snažím co nejvíce zpříjemnit našim pánům důstojníkům jich starosti a námahy. Byl jsem od pluku přeložen k maršbatalionu, což bylo mým nejvroucnějším přáním, abych mohl, byt’ i ze skromných prostředků, důstojnickou polní kuchyni na frontě uvésti v nejlepší koleje.

| Professor Herold |  | |||

| |||||

Herold was a university professor who Švejk had played mariáš (mariáge) with at U Valšů before the war (mentioned in an anecdote).

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Já konečně povídám: ,Pane Herolde, jsou tak laskav, hrajou durcha a neblbnou.’ Ale von se na mne utrh, že může hrát, co chce, abychom drželi hubu, von že má universitu. Ale to mu přišlo draze. Hostinský byl známej, číšnice byla s námi až moc důvěrná, tak jsme to tý patrole všechno vysvětlili, že je všechno v pořádku.

| Detective Chodounský |  | |||

| |||||

Chodounský was, in the long anecdote on detective Stendler, the owner of the detective bureau where the latter was employed.

Background

Chodounský was also in real life owner of a detective agency in Prague. His firm is listed in the address book for 1910. In the anecdote he is only mentioned by his last name.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Není ten Chodounský, co má soukromej detektivní ústav s tím vokem jako trojice boží, váš příbuznej?“ otázal se nevinně Švejk. „Já mám moc rád soukromý detektivy. Já jsem taky jednou sloužil před léty na vojně s jedním soukromýrn detektivem, s nějakým Stendlerem.

Literature

| Detective Stendler |  | |||

| |||||

Stendler was a man Švejk knew from his national service, with a cone-shaped skull, employed by detective Chodounský.

Background

Stendler was presumably a real person as detective Chodounský existed and may have emplyed him. How much of what is revealed in the anecdote is based on facts is however debatable.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Není ten Chodounský, co má soukromej detektivní ústav s tím vokem jako trojice boží, váš příbuznej?“ otázal se nevinně Švejk. „Já mám moc rád soukromý detektivy. Já jsem taky jednou sloužil před léty na vojně s jedním soukromýrn detektivem, s nějakým Stendlerem.

| Mr. Zemek |  | |||

| |||||

Zemek was caught in flagrante by detective Stendler, with Mrs. Grotová.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] A vona se otočila zády ke mně a bylo vidět na kůži, že má vobtisknutej celej vzorek toho mřížkování z koberce a na páteři jednu přilepenou hilznu z cigarety. »Vodpuste,« povídám, »pane Zemku, já jsem soukromej detektiv Stendler, vod Chodounskýho, a mám ouřední povinnost vás najít in flagranti na základě oznámení vaší paní manželky.

| Mrs. Grotová |  | |||

| |||||

Grotová was caught in flagrante delicto by detective Stendler, with Mr. Zemek.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] »Vodpuste,« povídám, »pane Zemku, já jsem soukromej detektiv Stendler, vod Chodounskýho, a mám ouřední povinnost vás najít in flagranti na základě oznámení vaší paní manželky. Tato dáma, s kterou zde udržujete nedovolený poměr, jest paní Grotová.« Nikdy jsem v životě neviděl takovýho klidnýho občana.

| Detective Stach |  | |||

| |||||

Stach worked for telephone operator Chodounský's competitor Mr. Stern and caught detective Stendler red-handed with Mrs. Grotová.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] ,A přitom jsem se,’ vyprávěl pan Stendler, ,pomalu začal vodstrojovat, a když už jsem byl vodstrojenej a celej zmámenej a divokej jako jelen v říji, vešel do pokoje můj dobrej známej Stach, taky soukromej detektiv, z našeho konkurenčního ústavu pana Sterna, kam se vobrátil pan Grot o pomoc, co se týká jeho paní, která prý má nějakou známost, a víc neřek než: »Aha, pan Stendler je in flagranti s paní Grotovou, gratuluji.

| Mr. Stern |  | |||

| |||||

Stern was the employer of detective Stach, and was entrusted by Mr. Grot to spy on his wife.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] ,A přitom jsem se,’ vyprávěl pan Stendler, ,pomalu začal vodstrojovat, a když už jsem byl vodstrojenej a celej zmámenej a divokej jako jelen v říji, vešel do pokoje můj dobrej známej Stach, taky soukromej detektiv, z našeho konkurenčního ústavu pana Sterna, kam se vobrátil pan Grot o pomoc, co se týká jeho paní, která prý má nějakou známost, a víc neřek než: »Aha, pan Stendler je in flagranti s paní Grotovou, gratuluji.

| Mr. Grot |  | |||

| |||||

Grot had commisioned Mr. Stern adn his agency to spy on his wife. The practical task was given to detective Stach who caught Mrs. Grotová and detective Stendler with their trousers down.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] ,A přitom jsem se,’ vyprávěl pan Stendler, ,pomalu začal vodstrojovat, a když už jsem byl vodstrojenej a celej zmámenej a divokej jako jelen v říji, vešel do pokoje můj dobrej známej Stach, taky soukromej detektiv, z našeho konkurenčního ústavu pana Sterna, kam se vobrátil pan Grot o pomoc, co se týká jeho paní, která prý má nějakou známost, a víc neřek než: »Aha, pan Stendler je in flagranti s paní Grotovou, gratuluji.

| Ganghofer, Ludwig |  | |||

| *7.7.1855 Kaufbeuren - †24.7.1920 Tegernsee | |||||

| |||||

,5.8.1885

Ludwig Ganghofer is made a pivotal figure in the staff carriage of the train between Moson and Győr through his novel Die Sünden der Väter, which is used as the key in Hauptmann Ságner's cipher system. The problem is simply that it is in two parts, and the officers have been given the first part instead of the intended second part. It is Kadett Biegler who discovers the mistake and embarrasses Ságner in front of his fellow officers. How it all happened is revealed in the conversation between Oberleutnant Lukáš and Švejk at the station in Győr.

The author states that it was a small book, a short story in two parts. It was indeed in two parts but it was a novel rather than a short story. Hauptmann Ságner also adds that "he doesn't write badly this Ganghofer", an opinion that no doubt reflects the author's own.

Background

Ludwig Ganghofer was a Bavarian writer who in his time was very popular, and many of his novels have been made it to the cinema. He was one of the favourite poets of Emperor Wilhelm II. and a personal friend of the emperor. Die Sünden der Väter (The sins of the fathers) (Adolf Bonz & Comp., Stuttgart, 1886) is one of the Ludwig Ganghofer's lesser known novels. Previous to its publication it had appeared as a serial in Neue Freie Presse from 5 August 1885. At the time the author lived in Vienna where he was dramatist at Ringtheater, and contributed to a couple of newspapers.

Whereas most of Ludwig Ganghofer's popular work was inspired and set in the Alpine surroundings of his home area, Die Sünden der Väter is an exception. It takes place in refined big city surroundings in Munich and Berlin and depicts a society that is very different from that of the Bavarian countryside.

War correspondent

Less known is his work as war reporter from 1915 to 1917. Although he exposed the horrors of war, his perspective is different from writers like Erich Maria Remarque and Jaroslav Hašek. He was a chauvinist who expressed pleasure when the destruction did not hit his own home country, and he wrote propaganda and slogans.

Die Front im Osten describes the early stages of the Gorlice-Tarnów offensive that Hašek later took part in. He includes a piece on the recapture of Przemyśl and a stay in Sambor in early June 1915 where he met k.u.k Stabsoffiziere[a]. In the autumn of 1915 he was severely wounded, was decorated with Eiserne Kreuz but carried on as a war correspondent until 1917. His political opinions were nationalistic and antidemocratic.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Ve štábním vagoně, kde seděli důstojníci pochodového praporu, panovalo ze začátku jízdy podivné ticho. Většina důstojníků byla zahloubána do malé knihy v plátěné vazbě s nadpisem „Die Sünden der Väter. Novelle von Ludwig Ganghofer“ a všichni byli současně zabráni do čtení stránky 161. Hejtman Ságner, batalionní velitel, stál u okna, v ruce držel tutéž knížku, maje ji taktéž otevřenu na stránce 161.

Literature

- Die Front im Osten, [a]

- Der russische Niederbruch,

- LUDWIG GANGHOFER - DIE PERSON,

- Ludwig Ganghofer,

- Die Sünden der Väter, ,5.8.1885

- "Die Sünden der Väter", Roman von Ludwig Ganghofer, ,19.6.1886

- Die Sünden der Väter, Roman von Ludwig Ganghofer, ,7.11.1886

- Večer u císaře Viléma v polí, ,29.1.1915

- Ludwig Ganghofers sechstiger Geburtstag, ,15.7.1915

| a | Die Front im Osten |

| Kronek, Martha |  | |||

| |||||

,7.8.1885

,20.1.1886

Kronek is a character in Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer and appears on page 161 of the second volume of the novel. Hašek refers to her as "some Marta".

Background

Martha was one of the main character of the novel Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer, she was an actress at Stadttheater in Munich. She is introduced after only a few pages and described as young and beautiful. Her mother also forms part of the plot[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Pánové,“ řekl se strašně tajuplným výrazem, „nezapomeňte nikdy na stránku 161!“ Zahloubáni do té stránky, nemohli si z toho ničeho vybrat. Že nějaká Marta, na té stránce, přistoupila k psacímu stolu a vytáhla odtud nějakou roli a uvažovala hlasitě, že obecenstvo musí cítit soustrast s hrdinou role.

Credit: Milan Hodík, Neue Freie Presse

Literature

- Die Sünden der Väter, ,5.8.1885 [a]

| a | Die Sünden der Väter | 5.8.1885 |

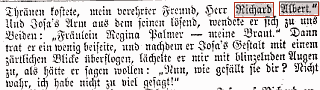

| Albert, Richard |  | |||

| |||||

,5.8.1885

,22.1.1886

Albert is a character from the novel Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer, mentioned on page 161 of the second part, like Marta. The author refers to him as "some Albert".

Background

given name Richard was the main hero of the Die Sünden der Väter and is introduced at the very beginning. In the serial version of the novel in Neue Freie Presse he appears already in the first part, dated 5 August 1885. He lives in Berlin, but is from Bavaria, just like the novels narrator. It is already obvious that he is well off.

In order to verify that Albert actually is mentioned on page 161 of the second part one would have to guess what print Hašek referred to and so far this information is not available.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Potom se ještě objevil na té stránce nějaký Albert, který neustále se snažil mluvit žertovně,což vytrženo z neznámého děje, který před tím předcházel, zdálo se takovou hovadinou, že nadporučík Lukáš překousl vzteky špičku na cigarety.

Credit: Milan Hodík, Neue Freie Presse

Literature

- Die Sünden der Väter, ,5.8.1885

| Bügler von Leuthold |  | |||

| |||||

Bügler von Leuthold was the noble name Kadett Biegler boasted that his forebears used.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Šel dobrovolně na vojnu a vykládal hned při první příležitosti veliteli školy jednoročních dobrovolníků, když se seznamoval s domácími poměry žáků, že jeho předkové se psali původně Büglerové z Leutholdů a že měli v erbu čapí křídlo s rybím ocasem.

| Archduke Albrecht |  | |||

| *3.8.1817 Wien - †18.8.1895 Arco | |||||

| |||||

Leon Battista Alberti

Erherzog Albrecht

Albrecht (his name) is murmured by Kadett Biegler when he hears about the ciphering-system based on the novel by Ludwig Ganghofer. Here he is indirectly referred to by "Archduke Albrecht's system".

Background

Albrecht was an Austrian archduke of the house of Habsburg, field marshal and inspector general of the Austro-Hungarian army. His father was Archduke Karl who lead the Austrian forces against Napoléon at Aspern in 1809.

It is however unlikely that this is the Albrecht that Kadett Biegler was mumbling about. Although being a prominent military leader there is no indication that he had any detailed knowledge of cryptography.

Alberti

Sergey Soloukh suggests that the person in question could be the Italian philosopher Leon Battista Alberti (1404 - 1472). He introduced a poly-alphabetic encryption system, albeit long before Gronveld (see Bronckhorst-Gronsveld). The chronology in Kadett Biegler's account is thus incorrect but otherwise the hypothesis seems solid.

Alberti is a prominent name in the history of cryptography and is often called "the father of western cryptography". It is therefore highly probable that Kadett Biegler (i.e. the author) got the names mixed up and actually meant "Alberti's system".

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Erzherzogs Albrecht system,“ zamumlal pro sebe snaživý kadet Biegler, „8922 = R, převzatý z methody Gronfelda.“ „Nový systém jest velice jednoduchý,“ zněl vagonem hlas hejtmanův. „Osobně obdržel jsem od pana plukovníka druhou knihu i informace.

Credit: Sergey Soloukh

Literature

- Erzherzog Albrecht ✟, ,18.2.1895

- Leon Battista Alberti,

| van Bronckhorst-Gronsveld, Joost Maximiliaan |  | |||

| *1598 Rimburg - †24.09.1662 Gronsveld | |||||

| |||||

Bronckhorst-Gronsveld (i.e. his name, indirectly by the Gronsveld-method) is mumbled by Kadett Biegler when he hears about the ciphering-system based on the novel Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer.

Background

Bronckhorst-Gronsveld was a Dutch count and Bavarian commander who is said to have invented the Gronsveld-method for ciphering, or more precisely: the polyalphabetic method of encryption. According to some sources the invention was done by his son Johann Franz.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Erzherzogs Albrechtsystem,“ zamumlal pro sebe snaživý kadet Biegler, „8922 = R, převzatý z methody Gronfelda.“ „Nový systém jest velice jednoduchý,“ zněl vagonem hlas hejtmanův. „Osobně obdržel jsem od pana plukovníka druhou knihu i informace.

Also written:GronfeldHašekJost Maximilian von Gronsfeldde

Literature

- Verschlüsselung nach Gronsfeld, ,13.4.2010

| Leutnant Dub |  | |||

| |||||

Dub is mentioned 237 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Dub was a Czech reserve-lieutenant and the biggest fool of the entire novel, disliked by officers and the rank and file alike. From around 23 May 1915 onwards he became Švejk's chief adversary but was an easy match for the cunning soldier. Dub had entered the plot earlier when Kadett Biegler revealed the gaffe about the Ludwig Ganghofer books, but he is only introduced as Švejk's main enemy in Budapest, after Biegler was forced to abandon that role due to his soiled trousers and resulting "cholera".

Dub was a school-master in civilian life and a keen monarchist, which made him a natural target for the author's scorn. Švejk had repeated clashes with him, but in the end had to come to his aid when he dragged him out of the whore-house in Sanok that Dub was "inspecting".

Dub is part of the story all the way to the end and suffers the ultimate indignity when he is thoroughly put in place by Kadett Biegler when they approach Żółtańce. Dub lived in Královská 18 in Smíchov. In the final section of Švejk, at the vicarage in Klimontów, Dub has the honour of uttering the final lines of the book, as idiotic as always.

Background

Attempts to find a "model" for Dub have not yielded any conclusive results. Most of the classical literature about Hašek is content to mention reserve lieutenant Emanuél Michálek who was suggested as a model by Jan Morávek already in 1924. Michálek is said to have used the phrase: "You don't know me, but...". He and the author served in 11. Kompanie for six weeks in 1915 and were allegedly at odds. That said, only the rank and this famous threatening phrase seem to link the literary figure to Michálek.

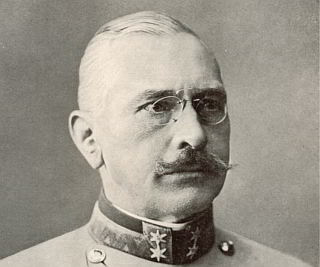

Johann Hutzler

Leutnant i. d. Res. Johann Hutzler

© Spolek Jednadevadesátníci

More convincing than the story by Jan Morávek is the thorough and well documented study by Karel Dub[a]. He concludes that the person who best fits the description of the literary lieutenant is Johann Hutzler, and that the name Dub probably was borrowed from someone Hašek knew from before the war or from České legie (19 persons carrying the surname Dub is listed in the database of the Legions, 12 of these in Russia). See Emanuél Michálek for more on Hutzler.

Robert Dub

Jan Eybl at his old age told journalists that he had served with a regimental doctor Dub who also knew Hašek. The main reason to be sceptical to this story is that the doctor according to official military records only joined the company after Hašek was captured! Otherwise almost every detail that Eybl provided has been verified.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Kadet Biegler se mezitím díval vítězně po všech a poručík Dub pošeptal nadporučíkovi Lukášovi, že to ,Čapí křídlo s rybím ocasem’ zjelo Ságnera jaksepatří.

[III.2] Poručík Dub podíval se rozzlobeně do bezstarostného obličeje dobrého vojáka Švejka a otázal se ho zlostně: „Znáte mne?“ „Znám vás, pane lajtnant.“ Poručík Dub zakoulel očima a zadupal: „Já vám povídám, že mě ještě neznáte.“ Švejk odpověděl opět s tím bezstarostným klidem, jako když hlásí raport: „Znám vás, pane lajtnant, jste, poslušně hlásím, od našeho maršbatalionu.“ „Vy mě ještě neznáte,“ křičel poznovu poručík Dub, „vy mne znáte možná s té dobré stránky, ale až mne poznáte s té špatné stránky. Já jsem zlý, nemyslete si, já každého přinutím až k pláči. Tak znáte mne, nebo mne neznáte?“ „Znám, pane lajtnant.“ „Já vám naposled říkám, že mne neznáte, vy osle. Máte nějaké bratry?“

Credit: Jan Morávek, Jan Ev. Eybl, Karel Dub

Literature

- Q(Rodokmen) či spíše Q(vývod) lajtnanta Duba, ,2009 [a]

- Záhadný Dub a Baloun, ,10.10.2017

| a | Rodokmen či spíše vývod lajtnanta Duba | 2009 |

| Kerckhoffs, Auguste |  | |||

| *19.1.1835 Nuth - †9.8.1903 Paris | |||||

| |||||

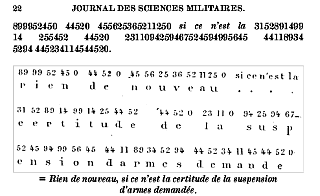

Kerckhoffs is mentioned by Kadett Biegler during the discussion with Hauptmann Ságner concerning the mysterious cryptographic key. See Ludwig Ganghofer.

Background

Kerckhoffs (full name Jean-Guillaume Hubert Victor François Alexandre Auguste Kerckhoffs van Nieuwenhoff) was a Dutch cryptographer and linguist, one of the founders of military cryptography.

In January and February 1883 he published his best known work on cryptography, La cryptographie militaire, an article that appeared in two parts in Journal des sciences militaires. It was regarded as one of the milestones of 19th century cryptography. Here he mentions both Oberleutnant Fleissner and Kircher.

Kadett Biegler is however wrong when he informs Hauptmann Ságner that this was a book. It was in fact a paper presented in two parts in the abovementioned periodical

Auguste Kerckhoffs, "La cryptographie militaire", 1883

Le colonel Fleissner (Handbuch der Kryptographie) a adopté, sans modification aucune, la méthode de déchiffrement du major Kasiski.

Le Père Kircher (Polygraphia nova et universalis ; Rome, 1663) a remplacé les lettres du tableau de Vigenère par des nombres, d’où le nom d’Abacus numeralis donné à son système.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Dovoluji si,“ řekl, „pane hejtmane, upozorniti na knihu Kerickhoffovu o vojenském šifrování. Knihu tu může si každý objednat ve vydavatelstvu ,Vojenského naučného slovníku’. Jest tam důkladně popsána, pane hejtmane, methoda, o které jste nám vypravoval.

Also written:KerickhoffHašek

Literature

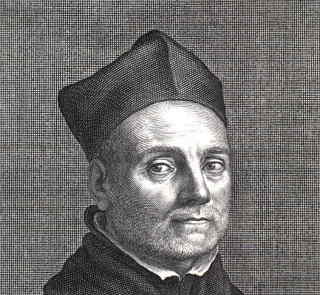

| Kircher, Anasthasius |  | |||

| *2.5.1601 Geisa - †27.11.1680 Roma | |||||

| |||||

Kircher was, according to Kadett Biegler, a colonel who had served in the Saxon army under Napoleón, mentioned by Biegler as the inventor of the method which was described in Kerckhoffs' book, and now in May 1915 appeared in a military train between Moson and Győr.

Background

Kircher surely does not refer to a colonel in the Saxon army, but rather the German scientist, universal genius and Jesuit father who is mentioned by Kerckhoffs in his paper La Cryptographie Militaire from 1883. His work, Polygraphia nova et universalis, 1663, is considered a principal work in cryptography.

He had an enormous range of interests: Egyptology, Sinology, bible studies, geology, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, acoustics, bacteriology, to name a few. He was also a practical inventor.

Auguste Kerckhoffs, "La cryptographie militaire", 1883

Le Père Kircher (Polygraphia nova et universalis ; Rome, 1663) a remplacé les lettres du tableau de Vigenère par des nombres, d’où le nom d’Abacus numeralis donné à son système. Seulement, au lieu d’écrire le texte cryptographique de la façon ordinaire, Kircher prend une page d’écriture quelconque, et indique les nombres du cryptogramme par des points placés sous les lettres, à des intervalles correspondant à la valeur des nombres obtenus. Schott a commenté le système du Père Kircher dans sa Schola stenographica ; de là que beaucoup d’auteurs, Larousse entre autres, lui en ont attribué la paternité.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Vynálezcem jejím je plukovník Kircher, sloužící za Napoleona I. ve vojsku saském. Kircherovo šifrování slovy, pane hejtmane. Každé slovo depeše se vykládá na protější stránce klíče.

Literature

- Die Geheimschreibekunst de Cabinete, ,4.5.1893

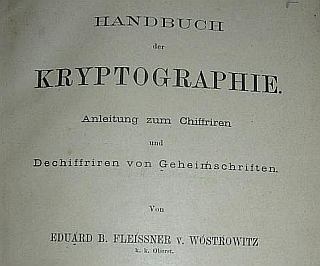

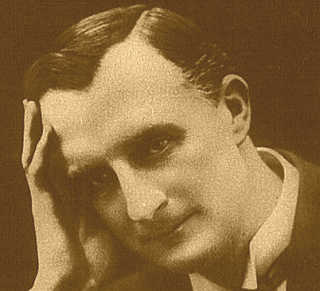

| Oberleutnant Fleissner von Wostrowitz, Eduard B. |  | |||

| *1825 Lemberg - †31.3.1888 Wien | |||||

| |||||

,22.11.1881

,1.5.1888

Fleissner was a senior lieutenant who, according to Kadett Biegler, improved the method invented by Kircher. He is said to have used Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer in an example in his book.

Background

Fleissner was in real life an Austrian colonel who in 1881 published Handbuch der Kryptographie. As Fleissner published the book five years before Die Sünden der Väter by Ludwig Ganghofer, the facts given by Kadett Biegler are dubious although all the names he mentions have some connection with cryptography. His book is briefly mentioned in the well known essay by Kerckhoffs from 1883.

The book was not published by Theresianische Militärakademie as Kadett Biegler claims. It was in fact self-published and distributed by L. W. Seidel & Sohn.

Fleissner had entered world literature even when still alive. He is mentioned in the novel Mathias Sandorf by Jules Verne already in 1885.

Auguste Kerckhoffs, "La cryptographie militaire", 1883

Le colonel Fleissner (Handbuch der Kryptographie) a adopté, sans modification aucune, la méthode de déchiffrement du major Kasiski.

Jules Verne, "Mathias Sandorf", 1885

Ces grilles, d’un si vieil usage, maintenant très perfectionnées d’après le système du colonel Fleissner, paraissent encore être le meilleur procédé et le plus sur, quand il s’agit d’obtenir un cryptogramme indéchiffrable.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Kircherovo šifrování slovy, pane hejtmane. Každé slovo depeše se vykládá na protější stránce klíče. Methoda ta zdokonalena nadporučíkem Fleissnerem v knize ,Handbuch der militärischen Kryptographie’, kterou si každý může koupit v nakladatelství vojenské akademie ve Víd. Novém Městě. Prosím, pane hejtmane.“

Literature

- Verzeichnis der Literarischen Werke ..., ,8.6.1881

- Handbuch der Kryptographie, ,12.11.1882

- Die Geheimschreibekunst de Cabinete, ,4.5.1893

- Fleissner-Chiffre,

- Mathias Sandorf,

| Ronovský |  | |||

| |||||

Ronovský is mentioned when Offiziersdiener Baloun just after arriving in Győr is so hungry that he shows signs of rebellion and Švejk finds it appropriate to put things in perspective by telling yet another story.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Ty máš nějakýho mladýho dědečka,“ řekl přívětivě, když dojeli do Rábu, „kerej se dovede pamatovat jen na tu vojnu v 66. roce. To já znám nějakýho Ronovskýho a ten měl dědečka, kerej byl v Italii ještě za roboty a sloužil tam svejch dvanáct let a domů přišel jako kaprál.

| Róža Šavaňů |  | |||

| *12.9.1841 Izsákfa - †9.4.1907 Tótvázsony | |||||

| |||||

József Savanyú

,26.6.1884

,16.5.1886

Róža Šavaňů is mentioned by Švejk when he tries to explain to Oberleutnant Lukáš how pointless it would be to start reading a book from the second volume. As an example he said that he once read a blood-dripping adventure book in two parts about Róža Šavaňů from the Bakony forest.

Background

Róža Šavaňů seems to refer to the Hungarian robber chief József Savanyú who terrorised the area around Bakony from around 1875 until 1884. Jaroslav Hašek also writes about Savanyú in the short story From the old prison in Ilava and in this story he is the main character[a].

József Savanyú

József "Jóska" Savanyú was the son of a shepherd and together with his brother he led an armed gang of robbers who were known for their ruthlessness and brutality. In connection with a church celebration on 29 June 1879 there was a shoot-out between the gang and the local police. His brother Istvan was killed but Jóska had a narrow escape. This incident appeared in the newspapers also in the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy. On 31 August 1881 he committed a murder and in April 1882 a wanted poster was issued, and there was also an announcement in the newspapers.

On 4 May 1884 he was finally arrested after having been caught in his sleep. The court case was held in Szombathely in 1886 and the verdict was given on 17 May. The gang leader was given life imprisonment and most of his accomplices given long prison sentences. There were 200 witnesses called up for the case. An appeal was lodged; first the main accused was handed a death sentence, but on 2 March 1887 the verdict was reverted to life imprisonment. Savanyú was sent to the prison in Ilava (now in Slovakia) but was freed on probation after 15 years. In the year 1900 newspapers reported that he had settled in his home village and opened a carpenter's shop.

Sándor Rózsa

Another inspiration may have been the legendary Hungarian robber Sándor Rózsa (1813-1878). His name was big enough to earn an obituary in the New York Times[b] and there were also novels written about him[c]. Milan Hodík and Grete Reiner both assume that this is the man Švejk has in mind, but most likely the good soldier gets the two criminals mixed up. The biographical details fit much better with the bandit from Bakony, but if any books were written about him is not known.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Já jsem byl, jak povídám,“ zněl na opuštěné koleji měkký hlas Švejkův, „taky téhož mínění. Jednou jsem koupil krvák vo Róžovi Šavaňů z Bakonskýho lesa a scházel tam první díl, tak jsem se musel dohadovat vo tom začátku, a ani v takovej raubířskej historii se neobejdete bez prvního dílu.

Credit: Petr Novák, Sergey Soloukh

Literature

- Ze staré trestnice v Ilavě, Jaroslav Hašek,1915 [a]

- Velká Kanidža a Körment, Jaroslav Hašek,26.4.1913

- Rozsa Sándor, král loupežníků a paličů, [c]

- Roza Sandor, ,22.10.1876

- Death of a "robber king", ,15.12.1878 [b]

- Ein Räuberbande vernichtet, ,9.7.1879

- Verhaftung eines Räuberhauptmannes, ,6.5.1884

- Freigelassene Raubmörder, ,30.12.1900

- Швейк. Комментарии. Шаг 68,

| a | Ze staré trestnice v Ilavě | Jaroslav Hašek | 1915 |

| b | Death of a "robber king" | 15.12.1878 | |

| c | Rozsa Sándor, král loupežníků a paličů |

| Metal caster Adamec |  | |||

| |||||

Adamec was a metal caster from the Daňkovka plant that Švejk starts to tell Oberleutnant Lukáš about before the latter cuts him off.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Nadporučík Lukáš mluvil takovým hlasem, jako by se o něho pokoušela horečka, a toho okamžiku, když umlkl, využitkoval Švejk k nevinné otázce: „Poslušně hlásím, pane obrlajtnant, za prominutí, proč se nikdy nedozvím, co jsem vyved hroznýho: Já, pane obrlajtnant, jsem se vopovážil na to zeptat jenom kvůli tomu, abych se příště mohl takový věci vystříhat, když se všeobecně povídá, že se vod chyby člověk učí, jako ten slejvač Adamec z Daňkovky, když se vomylem napil solný kyseliny...“

| Nikodém |  | |||

| |||||

Nikodém had died from galloping consumption in Budějovice bud was still on Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk's salary slip.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Kdyby mně ti lotři alespoň oznámili, jestli někdo není ve špitále. Ještě minulý měsíc ved jsem nějakého Nikodéma, a teprve při lénunku jsem se dozvěděl, že ten Nikodém zemřel v Budějovicích v nemocnici na rychlé souchotiny.

| Zugsführer Zyka |  | |||

| |||||

Zyka was a squad leader who didn't have the slightest overview of his squad, something which created disorder in Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk's papers.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] A nejhorší je u nás ten cuksfíra Zyka. Samý žert, samá anekdota, ale když mu oznamují, že je Kolařík odkomandován z jeho cuku k trénu, hlásí mně druhý den zas týž samý štand, jako by Kolařík dál se válel u kumpanie a u jeho cuku.

| Kolařík |  | |||

| |||||

Kolařík was a soldier who had been moved from Zyka´s squad without it showing in Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk's papers.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] A nejhorší je u nás ten cuksfíra Zyka. Samý žert, samá anekdota, ale když mu oznamují, že je Kolařík odkomandován z jeho cuku k trénu, hlásí mně druhý den zas týž samý štand, jako by Kolařík dál se válel u kumpanie a u jeho cuku.

| Kozel |  | |||

| |||||

Kozel was a postman Švejk told Offiziersdiener Baloun about in an anecdote.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Teď si představ, že by tu šunku z feldpošty poslali k nám do kumpačky a my jsme si s panem rechnungsfeldvéblem každej uřízli kousek, a vono by nám to zachutnalo, tak ještě kousek, až by to s tou šunkou dopadlo jako s jedním mým známým listonošem, nějakým Kozlem. Měl kostižer, tak mu napřed uřízli nohu pod kotník, potom pod koleno, potom stehno, a kdyby byl včas neumřel, byli by ho vořezali celýho jako prasklou tužku.

| čeledín Vomel |  | |||

| |||||

Vomel was Offiziersdiener Baloun's cattle boy at home who had warned him about the consequences of gluttony.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Měl jsem doma starýho čeledína Vomela a ten mě vždycky napomínal, abych jen tak nepejchnul, necpal se, že von pamatuje, jak mu jeho dědeček vypravoval dávno vo jednom takovým nedožerovi.

| Oberleutnant Šeba |  | |||

| |||||

Šeba was a senior lieutenant that Švejk knew from his time as a military servant for Oberleutnant Lukáš in Prague. This story puts Offiziersdiener Baloun in his place for having eaten his masters lunch, and Švejk emphasises how well he treated his obrlajtnant compared to how Oberleutnant Šeba's servant treated his superior.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Tak si vybral ten den nadívané holoubě. Já jsem si myslel, když mně dali půlku, že by si snad mohl pan obrlajtnant myslet, že jsem mu druhou půlku sežral, tak jsem ještě jednu porci koupil ze svýho a přines takovou nádhernou porci, že pan obrlajtnant Šeba, který ten den sháněl oběd a přišel právě před polednem na návštěvu k mýmu obrlajtnantovi, se taky najed.

| Ordonnanz Matušič |  | |||

| |||||

Matušič is mentioned 22 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Matušič was the messenger of Švejk's march battalion and appears regularly in the plot from now on, without ever playing a prominent role. He is playing cards with Offiziersdiener Batzer when Kadett Biegler wakes up from his legendary dream on the train to Budapest. In the dream he features as an angel and with Batzer he throws Biegler in the latrine on order from the Lord himself.

Background

Ordonnanz Matušič may well have a real life model. Jaroslav Hašek was transferred to the front with the XII. Marschbataillon of IR. 91, so a messenger in this unit could have been the inspiration. Given the author's usual projection of real field units into literary march units, the model should be looked for amongst Čeněk Sagner's battalion messengers by the III. Feldbataillon of IR. 91.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Pane kadet,“ řekl, „pan obrlajtnant poslal sem ordonanc Švejka, aby mu řek, co se stalo. Byl jsem teď u štábního vagonu a batalionsordonanc Matušič vás hledá z nařízení pana batalionskomandanta. Máte hned jít k panu hejtmanovi Ságnerovi.“

| General Woinovich von Belobreska, Emil |  | |||

| *23.4.1851 Petrinja - †13.2.1927 Wien | |||||

| |||||

,1908

Woinovich is mentioned in connection with post-cards the 11th march company has been given as compensation for the salami they were promised. The author correctly states that Woinovich was head of the War Archive. This is revealed during the tense conversation between Hauptmann Ságner and Kadett Biegler at the Győr railway station.

Background

Woinovich was a Austro-Hungarian general and military historian of Croatian descent who until 1915 was director of the War Archive in Vienna. Has was also author of 11 books, mainly on war history. A street in Vienna has been named after him.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Kadet Biegler podal veliteli batalionu dvě z těch pohlednic, které vydávalo ředitelství Vojenského válečného archivu ve Vídni, kde byl náčelníkem generál pěchoty Wojnowich. Na jedné straně byla karikatura ruského vojáka, ruského mužika se zarostlou bradou, kterého objímá kostlivec.

Also written:WojnowichHašekEmil Vojnovićhr

Literature

- Unteilbar und Untrennbar, ,1917

- Der Oberste Kriegsherr und sein Stab, ,1908

| Grey, Edward |  | |||

| *25.4.1862 London - †7.9.1933 Fallodon | |||||

| |||||

,12.5.1915

Sir Edward Grey is mentioned in connection with post-cards the 11th march company were given as compensation for the salami they were supposed to get on the way from Budapest eastwards to the front. One of the post-cards depicts Sir Edward Grey dangling from the gallows. He is also the target of a hate-poem from the collection The Iron Fist by the poet Greinz.

Background

Sir Edward Grey was British foreign secretary from 1905 to 1915 and played an important role in the events the led to the outbreak of war in 1914, although his diplomacy failed. He is criticized for not having communicated clearly to Germany that an invasion of Belgium would lead to war with Britain, but on the other hand he is given credit for persuading Italy to join the war on the side of the Entente.

A friend came to see me on one of the evenings of the last week — he thinks it was on Monday, August 3rd. We were standing at a window of my room in the Foreign Office. It was getting dusk, and the lamps were being lit in the space below... My friend recalls that I remarked on this with the words, "The lamps are going out all over Europe: we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime".

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Nahoře bylo: „Viribus unitis“ a pod tím obrázek, jak na šibenici visí Sir Edward Grey a dole pod ním vesele salutují rakouský i německý voják.

Literature

- Kriegs-Marterln, ,20.6.1915

| Greinz, Rudolf |  | |||

| *16.8.1866 Pradl - †16.8.1942 Innsbruck | |||||

| |||||

,12.5.1915

Greinz is mentioned in connection with post-cards the 11th march company has been given as compensation for the salami they should have got. Greinz is quoted from a poetry book, "The iron fist". Little jokes about our enemies, which contains a macabre poem about the British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey.

Background

Greinz was an Austrian author who in 1915 published the poetry book Die eiserne Faust. Marterln auf unsere Feinde.. A poem from this collection is quoted in the novel. Many other well-known people were also "honoured" in the collection: Nicholas Nikolaevich and Churchill are just a few examples.

The poem called "Grey" is quite accurately reproduced but Hašek seems to have got the translation of the book's title wrong: He translates "Marterl" as a "small joke" but it is actually a roadside shrine, often to commemorate someone who has died in an accident on that spot. A more common German word is "Bildstock". These shrines are commonplace in Austria, Bavaria and Czechia. Another source of confusion is that the end quote of the book's title is in the wrong place (surely not the author's fault), giving the impression that it is simply called "The Iron Fist".

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Básnička dole byla vzata z knížky Greinzovy: „Železná pěst“. Žertíčky na naše nepřátele, o kterých říšské listy psaly, že verše Greinzovy jsou rány karabáčem, přičemž obsahují pravý nezkrocený humor a nepřekonatelný vtip.

Literature

- Rudolf Heinrich Greinz (1866-1942),

- Kriegs-Marterln, ,20.6.1915

| Judas Iscariot |  | |||

| |||||

Judas to the right

Judas Iscariot is mentioned in the poem by Rudolf Greinz about Sir Edward Grey.

Background

Judas Iscariot was according to the New Testament one of the twelve original apostles of Jesus. He is best known for his role in betraying Jesus into the hands of Roman authorities. The name is a Greek form of Judah and has since been used as a byword for traitor, exemplified in this poem about Sir Edward Grey.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Na šibenici, v příjemné výši,

měl by se houpat Edward Grey,

je na to již nejvyšší čas,

však třeba upozornit vás,

že žádný dub své nepropůjčil dřevo

k popravě toho jidáše.

Also written:Jidáš IškariotskýczJudas Ischariotde

Literature

- Kriegs-Marterln, ,20.6.1915

| General Ritter von Herbert |  | |||

| |||||

Ordre de Bataille am 3/7. 1915.

© ÖStA

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien.

© VÚA

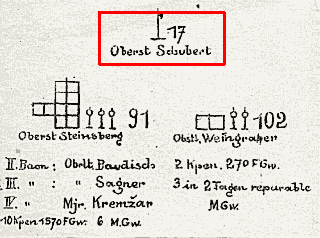

Ritter von Herbert signed a telegram containing orders about imminent departure to the front in Sokal. Hauptmann Ságner received it at Győr station. General Ritter von Herbert had dispatched a number of these telegrams, no encrypted. The telegram in question was also copied to the 14th march battalion of the 75th regiment.

The military station commander Bahnhofskommandant Zykán then informed Hauptmann Ságner that he had received a secret report from Divisional HQ that the brigade commander had gone mad and had been sent to Vienna. All his telegrams were to be ignored.

Background

General Ritter von Herbert was according to the novel an Austrian general and commander of the brigade Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 belonged to. Such a name is however not found in Schematismus, so he is obviously a fictional person. The closest candidates are the colonels Franz Herbert and Herbert Herberstein but none of them were assigned roles that were similar to the novel's Herbert[a]. Nor would a general have been in command of a brigade, these units were usually commanded by colonels. That said the author may well have picked up the story from real life; many officers broke down and reported sick in the course of the war.

According to Ordre de Bataille from 3 July 1915 Oberst Schubert is commander of 17. Infanteriebrigade, the unit that IR. 91 reported to. He was replaced by colonel Johann von Mossig on 17 July. On 13 September he in turn was replaced by colonel Alfred Steinsberg. Mossig however took up the position again a few weeks later as this was a temporary shift caused by illness further up the command chain.

The beginning in the next chapter continues the story of the insane brigade commander, and gives an interesting clue. There is talk about constructing a bridge across the Bug. IR. 91 was actually ordered to do this on 20 July (by Kamionka Strumiłowa), but were prevented by flooding, and that night they got a sudden order to march to Sokal. Could Schubert have been replaced due to ill health and thus served as an inspiration for Hašek's "Herbert"?

Replacement troops off track

As often happens in this (and other) novels the author used his licensia poetica to juggle events and facts. The order to build a bridge acroos the Bug and then suddenly get a counter-order to march to Sokal is authentic, but that this order was given to the march unit way behind the lines is mystification. No march battalion was ever involved in any of the operations by the Bug and Sokal, as they were usually dissolved at the moment they reached the front where the newly arrived troops were assigned to the existing field regiment. There is also a timing inconsistency: the 14th march battalions, including that of Infanterieregiment Nr. 75, were only moved to the front in mid September. This was six weeks after the battle of Sokal, and at the time the front had been pushed further east, by Dubno.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] První telegram musel být odevzdán, třebas měl obsah velice překvapující, když je batalion na stanici v Rábu: „Rychle uvařit a pak pochodem na Sokal.“ Adresován byl nešifrovaně na pochodový batalion 91. pluku s kopií na pochodový batalion 75. pluku, který byl ještě vzadu. Podpis byl správný: Velitel brigády: Ritter von Herbert.

[III.2] „Ten vyváděl, ten váš brigádní jenerál,“ řekl, chechtaje se na celé kolo, „ale doručit jsme vám tu blbost museli, poněvadž ještě nepřišlo od divise nařízení, že se jeho telegramy nemají dodávat adresátům.

Credit: Jaroslav Křížek, VÚA, ÖStA

Literature

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 709), ,1914 [a]

| a | Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 709) | 1914 |

| Kraft, Udo |  | |||

| *29.11.1870 Büdingen - †22.8.1914 Anloy | |||||

| |||||

,21.2.1915

Udo Kraft was a German teacher who was Kadett Biegler's role model. This is revealed in Biegler's disastrous conversation with Hauptmann Ságner as the train leaves Győr for Budapest. Biegler was just then reading Udo Kraft's Self-Education for Death for the Emperor, published by C.F. Amelang’s Verlag in Leipzig.

Background

Udo Kraft (Rudolf Karl Emil Kaspar Robert Kraft) was a German gymnasium teacher who enlisted as a volunteer when the war broke out. He was shot in the temple by Anloy in Belgium three weeks later, and died immediately. He served as a seargent with the 116th Infantry Regiment.

Bieglers description of the book is imprecise. Udo Kraft's book, a collection of letters and diaries, was published in early 1915, i.e. after his death. It was also a question of death for the fatherland, not for the emperor.

An English translation by Kenneth Kronenberg is available[a].

Selbsterziehung zum Tod fürs Vaterland. Aus den nachgelassenen Papieren des Kriegsfreiwilligen Prof. Udo Kraft.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Přál bych si, když padnu v boji, aby po mně zůstala památka, pane hejtmane. Mým vzorem je německý profesor Udo Kraft. Narodil se roku 1870, nyní ve světové válce přihlásil se dobrovolně a padl 22. srpna 1914 v Anloy. Před svou smrtí vydal knihu ,Sebevýchova pro smrt za císaře’.“

Credit: Kenneth Kronenberg, Volkmar Stein

Literature

- Udo Kraft, [a]

- Deutsche Verlustlisten (Pr. 46), ,9.10.1914

| a | Udo Kraft |

| General Mazzuchelli, Alois |  | |||

| *17.09.1776 Brescia - †05.08.1868 Vöslau | |||||

| |||||

Tages-Post, 12.8.1868

,12.8.1868

Mazzuchelli is mentioned in Kadett Biegler's notebook containing sketches of historical battle grounds. In this case it is regarding the battle of Trutnov.

Background

Mazzuchelli was an Austrian general who was pensioned in 1844 so that he commanded a division in the battle of Trutnov 27 June 1866 is out of question as he was 90 years old. Mazzuchelli was known as the proprietor of IR10 already from 1817 but it is unclear whether this regiment took part in the battle.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Kadet Biegler napsal: „Bitva u Trutnova neměla být svedena, poněvadž hornatá krajina znemožňovala rozvinutí divise generála Mazzucheliho, ohrožené silnými pruskými kolonami, nalézajícími se na výšinách obklopujících levé křídlo naší divise.“

Also written:MazzucheliHašek

Literature

| General von Benedek, Ludwig |  | |||

| *14.7.1804 Sopron - †27.4.1881 Graz | |||||

| |||||

,27.4.1881

Benedek is invoked by Hauptmann Ságner when he contemptuously calls Kadett Biegler "You Budweiser Benedek!"

Background

Benedek was an Austrian general and commander in chief of the Austrian forces during the Prusso-Austrian war of 1866. He was blamed for the disastrous defeat, immediately pensioned and put before a court martial. The trial was stopped by Emperor Franz Joseph I..

Benedek-kaserna i Brucker Lager er kalla opp etter han.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Podle vás bitva u Trutnova,“ řekl s úsměvem hejtman Ságner, vraceje sešitek kadetovi Bieglerovi, „mohla být svedena jedině v tom případě, kdyby Trutnov byl na rovině, vy budějovický Benedeku.

Literature

- Ludwig von Benedek, ,2001 - 2016

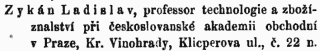

| Bahnhofskommandant Zykán |  | |||

| |||||

Professor Zykán was obviously never a station commander in Hungary but may at least have provided Hašek with a useful surname.

, 21.10.1892

Zykán was an active officer of unknown rank who was station commander in Győr. He was Czech and had attended Prager Infanteriekadettenschule with Hauptmann Ságner and Oberleutnant Lukáš. He and Ságner had a conversation at the station where it was revealed that even Ságner at the time had been a Czech patriot, standing up against the Austrianism at the school, but had later toned down his convictions to promote his career.

Background

It has not been possible to identify a model for this officer. The surname is not found in Schematismus from 1914 and is generally quite rare. In 2020 only 47 persons with this surname lived in Czechia and the vast majority of them were found in Beroun (15) and Prague (16).

Borrowed name

Because no officer Zykán can be identified we are at best left with the possibility of name borrowing, a method Hašek frequently used throughout the novel (Švejk, Břetislav Ludvík, Offiziersdiener Baloun a.o. are just some of the examples). Considering that Zykán is such a rare surname it appears surprisingly often in Hašek's stories. Some professor Zykán is mentioned in two of them and in a third a like-name soldier has a peripheral role. , 30.10.1916

The infantry man Alois Zykan served in the 11. Feldkompanie of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 which was also Hašek's company in 1915. Still we have no proof that their periods overlapped but the fact that the name also appeared in Hašek's story from 1916 about the Austrian captain Alserbach strengthens the link. Zykan was born in Vienna in 1889 and was shot in the head 10 September 1916 at the Isonzo front. He died in the garrison hospital in Ljubljana (Laibach) and was also buried there.

Professor Zykán

, 4.1898

The professor who Hašek wrote about was no doubt Ladislav Zykán (1859-1938). He taught technology and material science at Obchodní akademie where Hašek studied from 1889 to 1902 so the name may have been inspired by circumstances dating back as to the turn of the century. In the story Obchodní akademie Hašek provides correct details on him, and even adds where the professor lived[a]. According to Hašek he was also a former artillery officer but this is not entirely true: Zykán was reserve lieutenant in Infanterieregiment Nr. 88 (Beroun) until 1888. According to Hašek's final certificate Zykán was his teacher in three subjects.

Jaroslav Hašek: Obchodní akademie

Další důležitý předmět pro obchod jest technologie mechanická a nauka o zboží. Hlavně když to člověk umí od slova k slovu. Neboť máme velmi málo obchodníků v Čechách, kteří znají, jak se vyrábí benzín. Profesor Zykán, který předměty ony přednáší, jest velmi zbožný a býval dřív důstojníkem u dělostřelectva. Jest majitelem domu v Klicperově ulici na Královských Vinohradech. Slušné, zámožné posluchače má rád.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Poslyš, Lukáši,“obrátil se k nadporučíkovi, „máš kadeta Bieglera u své kumpanie, tak ho, hocha, cepuj. Podpisuje se, že je důstojník, ať si to v gefechtu zaslouží. Až bude trommelfeuer a my budem atakovat, ať se svým cukem stříhá drahthindernissy, der gute Junge. Á propos, dá tě pozdravovat Zykán, je velitelem nádraží v Rábu.“

Literature

- Obchodní akademie, Jaroslav Hašek,18.10.1909 [a]

- Bilance válečného tažení hejtmana Alserbacha, Jaroslav Hašek,7.8.1916J

- Feulleton (V rakouském parlamentě...), Jaroslav Hašek,10.12.1917J

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství, ,1851 - 1914

- Militärschematismus, ,1888

- Umrtí, ,27.8.1938

| a | Obchodní akademie | Jaroslav Hašek | 18.10.1909 |

| Offiziersdiener Batzer |  | |||

| |||||

Batzer and Matušič

Batzer is mentioned 11 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Batzer was the servant of Hauptmann Ságner and came from the area around Kašperské Hory. He and Ordonnanz Matušič are playing cards in the carriage where Kadett Biegler fight through his dream on the train to Budapest. These two discover the pungent disaster in Biegler's trousers and call their superior. Matušič and Batzer also appear in the dream as arch angels.

The author gives three dialect samples from Batzer, and he doesn't hide his dislike for this "horrible" variant of German (it is a Bavarian dialect).

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Šel kolem zadního kupé, kde hrál batalionsordonanc Matušič se sluhou velitele praporu Batzerem vídeňskou hru šnopsa. Dívaje se do otevřených dveří kupé, zakašlal. Otočili se a hráli dál. „Nevíte, co se patří?“ otázal se kadet Biegler. „Nemoh jsem,“ odpověděl sluha hejtmana Ságnera Batzer svou strašnou němčinou od Kašperských Hor, „mi’ is’ ď Trump’ ausganga".

[III.1] „Stink awer ď Kerl wie a’Stockfisch,“ prohodil Batzer, který pozoroval se zájmem, jak sebou spící kadet Biegler povážlivě vrtí, „muß’ ďHosen voll ha’n.“

[III.1] Poněvadž se opět při těch slovech počal obracet, zavonělo to Batzerovi intensivně pod nos, takže poznamenal odplivuje si: „Stink wie a’ Haizlputza, wie a’ bescheißena Haizlputza.“

| Fürst zu Schwarzenberg, Karl Philipp |  | |||

| *18.4.1771 Wien - †15.10.1820 Leipzig | |||||

| |||||

Schwarzenberg enters the dream of Kadett Biegler when he deals with the Battle of the Nations by Leipzig in 1813.

Background

Schwarzenberg was an Austrian nobleman, diplomat and Field Marshal. He was commander of the coalition forces (Austria, Prussia, Russia, Sweden) at the battle of Leipzig in 1813. The battle was a decisive defeat for Napoléon and the following year Schwarzenberg led his forces into Paris.

Schwarzenberg hailed from the Bohemian branch of the family. He was first buried in Třeboň but his sarcophagus was later moved to the family's burial chapel in Kožlí u Orlíka near Písek.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Znáte dějiny bitvy národů u Lipska?“ otázal se, „když polní maršálek kníže Schwarzenberg šel na Liebertkovice 14. října roku 1813 a když 16. října byl zápas o Lindenau, boje generála Merweldta, a když rakouská vojska byla ve Wachavě a když 19. října padlo Lipsko?“

Also written:Karel Filip Schwarzenbergcz

| General von Merveldt, Maximilian Friedrich |  | |||

| *29.6.1764 Münster - †5.7.1815 London | |||||

| |||||

Merveldt enters the dream of Kadett Biegler when he deals with the Battle of the Nations by Leipzig in 1813.

Background

Merveldt was a German diplomat and general who served Austria. He commanded an army at the battle of Leipzig, but was captured after approaching a group of Poles and Saxons he thought were Hungarians. He died when he was ambassador in London, and was given a honorary burial in Westminster Abbey.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] „Znáte dějiny bitvy národů u Lipska?“ otázal se, „když polní maršálek kníže Schwarzenberg šel na Liebertkovice 14. října roku 1813 a když 16. října byl zápas o Lindenau, boje generála Merweldta, a když rakouská vojska byla ve Wachavě a když 19. října padlo Lipsko?“

Also written:MerweldtHašek

| General Dankl von Kraśnik, Viktor |  | |||

| *18.8.1854 Udine - †8.1.1941 Innsbruck | |||||

| |||||

Dankl enters the dream of Kadett Biegler, there is a portrait of him hanging on the wall of the k.u.k. Gottes Hauptquartier.

Background

Dankl was an Austro-Hungarian general and one of the principal military leaders between 1914 and his retirement in 1916. He was commander of the 1st army by outbreak of war and was supreme commander at the battle of Kraśnik, the first battle the army of Austria-Hungary won.

In 1915 he become commander of the Austro-Hungarian forces on the Italian front, and did a good job until he was replaced in 1916 due to poor health.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Uprostřed pokoje, ve kterém po stěnách visely podobizny Františka Josefa a Viléma, následníka trůnu Karla Františka Josefa, generála Viktora Dankla, arcivévody Bedřicha a šéfa generálního štábu Konráda z Hötzendorfu, stál pán bůh.

Literature

- Viktor Graf Dankl von Kraśnik, ,2001 - 2016

| Archduke Friedrich |  | |||

| *4.6.1856 Židlochovice (Gross-Seelowitz) - †30.12.1936 Mosonmagyaróvár | |||||

| |||||

Friedrich enters the horrible dream of Kadett Biegler, there is a portrait of him hanging on the wall of the k.u.k. Gottes Hauptquartier.

Background

Friedrich was an Austro-Hungarian general and archduke, known for his immense wealth. From 1914 to 1917 he was Inspector General of the Royal and Imperial armed forces and thus formally held the highest position, but in reality Feldmarschall Conrad had the decisive power in operational matters.

Towards the end of the war Friedrich had become very unpopular, accused of military incompetence and for having used the war to enrich himself. The successor states of Austria-Hungary confiscated nearly all his property. He was the brother of Archduke Stephan.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí Friedrich is mentioned during Švejk's stay at a psychiatric clinic in Vienna. One of the inmates claims to be the archduke and that "we will be in Moscow in a month".[1]

Tam v rohu chodby seděl například člověk, kaprál, který křičel, že je arcivévoda Bedřich a že za měsíc bude v Moskvě. Toho zavřeli na pozorování, ale nesmíme zapomenouti že skutečný arcivévoda Bedřich se jednou sám tak vyjádřil a nestalo se mu nic, jen utrpěl trochu blamáže.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] Uprostřed pokoje, ve kterém po stěnách visely podobizny Františka Josefa a Viléma, následníka trůnu Karla Františka Josefa, generála Viktora Dankla, arcivévody Bedřicha a šéfa generálního štábu Konráda z Hötzendorfu, stál pán bůh.

Also written:Arcivévoda Bedřichcz

Literature

- Feldmarschall Erzherzog Friedrich, ,11.12.1914

- Bilance válečného tažení hejtmana Alserbacha, Jaroslav Hašek,7.8.1916J

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Doctor Welfer, Friedrich |  | |||

| |||||

Welfer was a "war doctor" who had lived very well as a student on a grant from a deceased uncle. He would receive the grant every year until he had graduated. The pay-out was four times higher than an expected salary so the studies dragged on until the war wrecked it all. Now, in Budapest, he had to see to Kadett Biegler who had shitted his trousers full after his nasty dream on the train.

Quote(s) from the novel

[III.1] K batalionu byl přidělen „válečný doktor“, starý medik a buršák Welfer. Znal pít, rvát se a přitom měl medicinu v malíčku. Prodělal medicinské fakulty v různých universitních městech v Rakousko-Uhersku, i praxi v nejrozmanitějších nemocnicích, ale doktorát neskládal prostě z toho důvodu, že v závěti, kterou zanechal jeho strýc svým dědicům, bylo to, že se má vyplácet stud. mediciny Bedřichu Welferovi ročně stipendium do té doby, kdy obdrží Bedřich Welfer lékařský diplom.

Also written:Bedřich Welfercz

| Major Koch |  | |||

| |||||

Robert Koch discovered the cholera germ.

Koch was a captain (or major) who had died of cholera and was to be buried in Budapest together with Kadett Biegler (who the doctors thought would soon die). One of the doctors had earlier referred to Koch as a major. It is also mentioned that Koch has the same surname as the inventor of the cholera germ.

Background

In 1914 there were several officers named Koch in k.u.k. Heer, amongst them three captains and one major. None of them served in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 or any of the other regiments from Bohemia. That said the dead officer in Budapest may obviously have been from other army unit.

Captain or major?

In his translation of The Good Soldier Švejk into English Cecil Parrott corrected Hašek's incoherent use of "captain" and "major", and decided that Koch was a major. Antonín Brousek, German translator of the novel, makes the same assumption.

Quote(s) from the novel