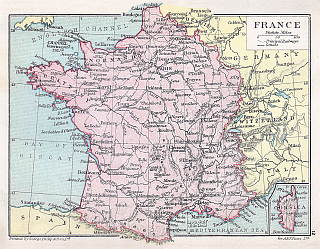

Švejk's journey on a of Austria-Hungary from 1914, showing the military districts of k.u.k. Heer. The entire plot of The Good Soldier Švejk is set on the territory of the former Dual Monarchy.

The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (mostly known as The Good Soldier Švejk) by Jaroslav Hašek is a novel that contains a wealth of geographical references - either directly through the plot, in dialogues or in the author's narrative. Hašek was himself unusually well travelled and had a photographic memory of geographical (and other) details. It is evident that he put a lot of emphasis on geography: Eight of the 27 chapter headlines in the novel contain geographical names.

This web site will in due course contain a full overview of all the geographical references in the novel; from Prague in the introduction to Klimontów in the unfinished Part Four. Continents, states (also defunct), cities, market squares, city gates, regions, districts, towns, villages, mountains, mountain passes, oceans, lakes, rivers, caves, channels, islands, streets, parks and bridges are included.

The list is sorted according to the order in which the names appear in the novel. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's translation from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by these examples: Sanok a location where the plot takes place, Dubno mentioned in the narrative, Zagreb part of a dialogue, and Pakoměřice mentioned in an anecdote.

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60) II. At the front

II. At the front  2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (38)

1. Across Magyaria (38) 2. In Budapest (38)

2. In Budapest (38) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50) 4. Forward March! (42)

4. Forward March! (42)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war | |||

| Konopiště |  | |||

| |||||

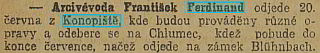

,2.9.1910

,19.6.1914

Konopiště is mentioned by Mrs. Müllerová already in the opening passage as she explains Švejk which Ferdinand has been murdered: "the Archduke Ferdinand, the one from Konopiště, the fat one, the religious one".

Background

Konopiště is a village and castle by Benešov that from 1887 to 1914 was owned by Archduke Franz Ferdinand, then Austrian heir to the throne. He and his family lived there for long periods. The castle is now a museum which exhibits amongst other items, Franz Ferdinand's around 475,000 hunting trophies and large amounts of classic furniture and paintings.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Konopiště had 483 inhabitants of whom 463 (95 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Benešov, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Benešov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Konopiště were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 102 (Beneschau) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Pisek).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Ale, milostpane, pana arcivévodu Ferdinanda, toho z Konopiště, toho tlustýho, nábožnýho.“ „Ježíšmarjá,“ vykřikl Švejk, „to je dobrý. A kde se mu to, panu arcivévodovi, stalo?“ „Práskli ho v Sarajevu, milostpane, z revolveru, vědí. Jel tam s tou svou arcikněžnou v automobilu.“

Also written:KonopistBang-HansenKonopischtde

| Sarajevo |  | |||

| |||||

Sarajevo city hall, scene of the attack.

K vítězné svobodě 1914-1918-1928, ,1928

Sarajevo is first mentioned by Mrs. Müllerová as she tells Švejk about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Later in the chapter the conversation at U kalicha revolves around the murder on the emperor-to-be and Sarajevo is mentioned many times by detective Bretschneider, Švejk and pubkeeper Palivec.

Background

Sarajevo was in 1914 as now the capital of Bosnia-Hercegovina. In 1878 Austria-Hungary occupied the area although it formally remained a part of Turkey until 1908 when it was annexed.

The Bosnian capital was on 28 June 1914 the scene of the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne. This act set in motion the events that a month later led to the outbreak of World War I. The killing was carried out by Serbian nationalists but it has not been proved that the Serbian government was involved.

The murders in Sarajevo is very directly the starting point of the novel these web pages are about.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Práskli ho v Sarajevu, milostpane, z revolveru, vědí. Jel tam s tou svou arcikněžnou v automobilu.“ „Tak se podívejme, paní Müllerová, v automobilu. Jó, takovej pán si to může dovolit, a ani nepomyslí, jak taková jízda automobilem může nešťastně skončit. A v Sarajevu k tomu, to je v Bosně, paní Müllerová. To asi udělali Turci. My holt jsme jim tu Bosnu a Hercegovinu neměli brát.

Literature

| Bosnia |  | |||

| |||||

,1893

Bosnia is first mentioned by Švejk when he states to Mrs. Müllerová that Sarajevo is in Bosnia. Later, during the conversations at U kalicha mellom detective Bretschneider, pubkeeper Palivec and Švejk, and the area is mentioned several times. In Budapest a Bosnian regiment is mentioned.

Background

Bosnia is often mentioned together with Hercegovina as Bosnia-Hercegovina. This is the political unit that both areas belong to. Bosnia and Hercegovina have long been purely geographical terms.

The area was annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908. This led to widespread dissatisfaction amongst serbs and is arguably the main reason for the grievances that led terrorists to plot and execute the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1814.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „A v Sarajevu k tomu, to je v Bosně, paní Müllerová. To asi udělali Turci. My holt jsme jim tu Bosnu a Hercegovinu neměli brát."

[III.1] Zato už v Bosně jsme ani vodu nedostali. Ale do Bosny, ačkoliv to bylo zakázané, měli jsme různých kořalek, co hrdlo ráčilo, a vína potoky. Pamatuji se, že na jedné stanici nás nějaké paničky a slečinky uctívaly pivem a my jsme se jim do konve s pivem vymočili, a ty jely od vagónu!

Also written:BosnaczBosniendeBosnahrБоснаsr

| Bosnia-Hercegovina |  | |||

| |||||

,1893

Bosnia-Hercegovina is mentioned 4 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Bosnia-Hercegovina is first mentioned by Švejk when he states to Mrs. Müllerová at Sarajevo ligg i Bosnia and that Austria-Hungary shouldn't have taken it from the Turks. Later on the area is mentioned in the conversation at U kalicha between detective Bretschneider, pubkeeper Palivec og Švejk.

Background

Bosnia-Hercegovina was (and is) the political entity consisting of Bosnia and Hercegovina. The area was annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908. This led to widespread dissatisfaction amongst Serbs and is arguably the main reason for the grievances that led terrorists to plot and carry out the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand six years later.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „A v Sarajevu k tomu, to je v Bosně, paní Müllerová. To asi udělali Turci. My holt jsme jim tu Bosnu a Hercegovinu neměli brát."

[I.1] "V tuhle dobu bývá v Bosně a Hercegovině strašný horko. Když jsem tam sloužil, tak museli dávat našemu obrlajtnantovi led na hlavu." "U kterého pluku jste sloužil, pane hostinský?"

[I.1] "V tom Sarajevu," navazoval Bretschneider, "to udělali Srbové." "To se mýlíte," odpověděl Švejk, "udělali to Turci, kvůli Bosně a Hercegovině."

[IV.3] Jurajda mluvil dál: "V jednom statku přišel jsem na jednoho starého, vysloužilého vojáka z doby okupace Bosny a Hercegoviny který vysloužil vojenskou službu v Pardubicích u hulánů a ještě dnes nezapomněl česky. Ten se se mnou začal hádat, že v Čechách se nedává do jitrnic marjánka, ale heřmánek.

Also written:Bosna a HercegovinaczBosnien und HerzegowinadeBosna i HercegovinahrBosnia og HercegovinannБосна и Херцеговинаsr

| Nusle |  | |||

| |||||

Nusle is first mentioned by Mrs. Müllerová when she refers to an assault with a revolver which took place there in her home town. The area is later referred to by pubkeeper Palivec at U kalicha and it is obvious that Nusle had a bad reputation at the time. There are several references to locations in Nusle later in the novel, the tavern U Bansethů being amongst them.

Background

Nusle was from 1898 a town in the Prague conurbation that grew rapidly during the industrial revolution. Riegrovo náměstí (now Náměstí Bratří Synků) was regarded the centre of the town. In 1922 it became part of greater Prague.

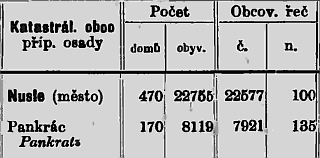

Demography

According to the 1910 census Nusle had 30,874 inhabitants of whom 30,498 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Nusle, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Královské Vinohrady.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Nusle were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Nedávno taky si hrál jeden pán u nás v Nuslích s revolverem a postřílel celou rodinu i domovníka, kterej se šel podívat, kdo to tam střílí ve třetím poschodí.“

Literature

| Switzerland |  | |||

| |||||

,1914

General Ulrich Wille, Swiss commander-in-chief during World War I.

,6.11.1904

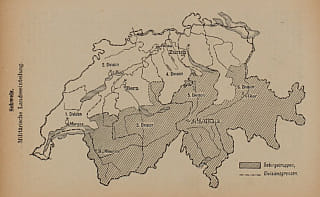

Switzerland provides in an anecdote by Švejk refuge for a guard who had lent his braces to an inmate who had murdered a captain. The prisoner hung himself with the braces. The guard got 6 months but escaped to Switzerland.>

Background

Switzerland was neutral during World War I and was in 1914 like today a federal republic. As a curiosity it must be mentioned that the Habsburg family hailed from Switzerland. During World War I Lenin lived in Switzerland. He was from 1917 to play an important role in the events leading to Russia's withdrawal from the war.

In addition Switzerland was during the war at times a place of refuge for Professor Masaryk and other Czechs who worked for national independence.

Hašek in Switzerland

Jaroslav Hašek wrote several stories set in Switzerland and by all accounts he visited the country in 1904. Although this can't be confirmed by other sources than the author himself, the fact that he usually based his stories from places he knew, gives a strong indication. In one story he wrote that he walked from Switzerland through Bavaria back to Domažlice. The trip must have taken place in the time-span July to September.

The first story with a Swiss setting was published in Národní listy already on 6 November 1904 and was called Oslík Guat (Guat the Donkey)[a] and takes place in the Bernese Alps. None of the places where the plot takes place can be identified according to the author's spelling. These places were "Dünsingen", "Tillingen", "Stroschein" and "Gallensheim". Mentioned in passing are Bern and Lake Constance. In the story Výprava na Moasserspitze[b] the narrator writes that he stayed in Bern and prepared an excursion to "Moasernspitze, six hours away, in the canton Bern". The summit is said to have been pointed, but none of the spelling variations give an indication of which mountain he meant. The narrator also informs that the stay took place at the end of June, a timing that is at odds with the author's known whereabouts at the time.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] To vědí, paní Müllerová, že v takový situaci jde každému hlava kolem. Profousa za to degradovali a dali mu šest měsíců. Ale von si je nevodseděl. Utek do Švejcar a dneska tam dělá kazatele ňáký církve.

Credit: Radko Pytlík

Also written:ŠvýcarskoczSchweizdeSuissefrSvizzeraitŠvejcarŠvejk

Literature

- Veltzés Internationaler Armee-Almanach, ,1914

- Oslík Guat, Jaroslav Hašek,6.11.1904 [a]

- Výprava na Moasserspitze, Jaroslav Hašek,16.6.1907 [b]

| a | Oslík Guat | Jaroslav Hašek | 6.11.1904 |

| b | Výprava na Moasserspitze | Jaroslav Hašek | 16.6.1907 |

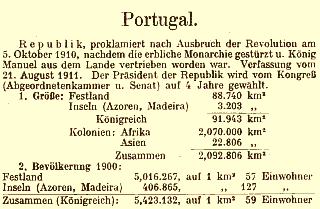

| Portugal |  | |||

| |||||

Hoisting the Portuguese flag during World War I.

,1914

Portugal is referred to by Švejk when he talks about the killing of a fat king of Portugal. This surely refers to the assassination of King Carlos I. I of the house Bragança in 1908.

Background

Portugal was in 1914 a republic which still kept some colonies, mostly in Africa. At the beginning of the 20th century Portugal experienced a power struggle between reformist and conservative groups. The republicans gained the upper hand, and a republic was established in 1910, two years after the murder of the king and the crown prince.

On 9 March 1916 Germany declared war on Portugal and Portuguese forces took part in Africa and on the western front. Several Portuguese ships were sunk by German U-boats during the war.

After the war, Karl, the last Habsburg emperor, sought refuge in Portugal and he died at Madeira. See Archduke Karl Franz Joseph.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Jestli se pamatujou, jak tenkrát v Portugalsku si postříleli toho svýho krále. Byl taky takovej tlustej.

Also written:Portugalskocz

Literature

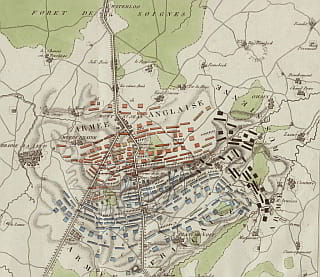

| Waterloo |  | |||

| |||||

Waterloo and the famous battle there is mentioned by the author when he describes the pub landlord pubkeeper Palivec and his knowledge of Victor Hugo.

Švejk also mentions Waterloo in [II.1] when on the train to Tábor, again in the context of Napoléon.

Background

Waterloo is a town in Walloon-Brabant in Belgium, near Brussels.

The town is known because of the famous battle that took place nearby on 18 June 1815, when Wellington and Blücher were victorious against Napoléon's French army. The battle took place at Mont-Saint-Jean south of the town and meant the end of Napoleon's political and military career.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Palivec byl známý sprosťák, každé jeho druhé slovo byla zadnice nebo hovno. Přitom byl ale sečtělý a upozorňoval každého, aby si přečetl, co napsal o posledním předmětě Victor Hugo, když líčil poslední odpověď staré gardy Napoleona Angličanům v bitvě u Waterloo.

[II.1] Napoleon se u Waterloo vopozdil vo pět minut, a byl v hajzlu s celou svou slávou..."

Literature

- Jak jsem vystoupil ze strany Nár. sociální, Jaroslav Hašek,14.3.1912

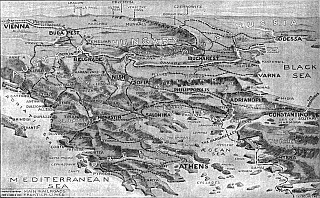

| Balkans |  | |||

| |||||

The New York Times Current History, March 1915

Balkans is mentioned once by Švejk in the conversation at U kalicha. Later the peninsula appears in the conversation between hop trader Wendler and Oberleutnant Lukáš.

Background

Balkans was at the start of the 20th century the least stable part of Europe. The two Balkan Wars had been fought in 1912 and 1913; first Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro against Turkey, then Serbia, Montenegro and Greece against Bulgaria.

In the Second Balkan War, Romania and Turkey joined the war against Bulgaria when they realised that these were about to loose. Serbia got out of these wars politically strengthened, a fact which made Austria-Hungary increasingly uneasy and which may have contributed to their uncompromising stance in 1914.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] A Švejk vyložil svůj názor na mezinárodní politiku Rakouska na Balkáně. Turci to prohráli v roce 1912 se Srbskem, Bulharskem a Řeckem. Chtěli, aby jim Rakousko pomohlo, a když se to nestalo, střelili Ferdinanda.

[I.14.5] Pro chmel je nyní ztracena Francie, Anglie, Rusko i Balkán.

Also written:Balkáncz

Literature

- Zprávy z Turnova, ,24.11.1912

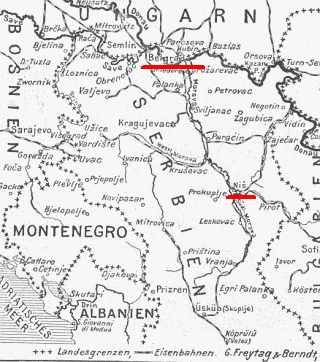

| Serbia |  | |||

| |||||

,9.8.1914

,1914

,1914

Serbia is mentioned 35 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Serbia is first mentioned in the conversation at U kalicha between Švejk and detective Bretschneider about the Balkans. Thereafter it reappears repeatedly, the slogan Heil, nieder mit den Serben! is quoted a few times.

From Part Two onwards the Serbian army, irregulars and civilians are often mentioned in stories told by veterans from the campaign against Serbia. Amongst those who served there were Sappeur Vodička, Oberst Schröder, Hauptmann Ságner, and Major Wenzl.

Background

Serbia was in 1914 a kingdom on the Balkans that played a key role during the outbreak of World War I. Austria-Hungary made the Serbian government responsible for the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones. Serbia was the first country declared war on, and the first country to see fighting. Serbia stood up well against the forces of the Dual Monarchy and repelled three invasions in 1914, despite suffering heavy losses themselves. But after Bulgaria entered the war and German forces assisted the Austrians, their resistance was broken in October 1915.

Serbia was the country that relative to population figures suffered the worst losses in the war (indeed in any modern European conflict): roughly 27% of the population perished, many of them in the worst typhus epidemic known in history.

The borders of Serbia were in 1914 somewhat different from today. The kingdom included Macedonia but not Vojvodina and Banat which at the time were part of Austria-Hungary. The capital was (and still is) Belgrade.

The 91st regiment in Serbia

Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 was sent to the Serbian front immediately after the outbreak of war and took part in all three invasions. They spent most of the time between 15 August and 15 December 1914 on Serbian territory. Their losses were frightening and when they finally withdrew across the Danube by Belgrade they were, like the rest of the invading army, utterly decimated. Several officers that later provided prototypes for Švejk's superiors took part in the campaign: Franz Wenzel, Čeněk Sagner, Rudolf Lukas, Josef Adamička and Jan Eybl. Every one of them apart from Eybl (he was there only the last three weeks) were at some stage injured or reported sick.

At the beginning of October 1918 the regiment was, as part of the 9. Infanteriedivision, sent back to Serbia (Vranje south of Niš) because Bulgaria had pulled out of the war and their forces needed to be replaced. This was eventually one long retreat northwards in an army that was by now disintegrating. Hans Bigler was the only prototype of figures in The Good Soldier Švejk that took place in this desparate campain and he ended by being captured.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the country is briefly mentioned at the start of chapter 5. The author notes that the Austrian army was in trouble in Serbia, in Prague people were happy and in Moravia they were preparing cakes to welcome the cossacks. This had happened when Švejk was in prison at the start of the war.[1]

Mezitím co byl Švejk zavřen, ruská vojska zabrala Lvov, oblehla Přemyšl, dole v Srbsku stálo to také velmi špatně s rakouskou armádou, lidé v Praze byli veselí a na Moravě dělali již přípravy k pečení koláčů, až přijdou kozáci.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] A Švejk vyložil svůj názor na mezinárodní politiku Rakouska na Balkáně. Turci to prohráli v roce 1912 se Srbskem, Bulharskem a Řeckem. Chtěli, aby jim Rakousko pomohlo, a když se to nestalo, střelili Ferdinanda.

[I.9] Byly to fotografie různých exekucí, provedených armádou v Haliči a v Srbsku. Umělecké fotografie s vypálenými chalupami a se stromy, jichž větve se skláněly pod tíhou oběšených. Zejména pěkná byla fotografie ze Srbska s pověšenou rodinou.

[I.10.1] U samých dveří seděl voják s několika civilisty a vykládal jim o svém zranění v Srbsku. Měl obvázanou ruku, plné kapsy cigaret, které od nich dostal.

[I.11.2] Drožkář byl rebelant. Dělal různé poznámky o vítězství rakouských zbraní, jako: „Ti vám to v Srbsku nahnuli“ a pod. Když přejížděli potravní čáru, ptal se zřízenec, co vezou.

[I.12] Když se pak hnuli, musel s nimi a dostal se až do Uher, kde někde poprosil taky někoho, aby mu počkal u vozu, a tím se jedině zachránil, a to by ho táhli do Srbska.

[I.13] Nadporučík Machek zajat v Srbsku, dluhuje mně 1500 korun. Je zde víc takových lidí. Ten padne v Karpatech s mou nezaplacenou směnkou, ten jde do zajetí, ten se mně utopí v Srbsku, ten umře v Uhrách ve špitále.

[I.14.4] Švejk posadil se na lavici ve vratech a vykládal, že v bitevní frontě karpatské se útoky vojska ztroskotaly, na druhé straně však že velitel Přemyšlu, generál Kusmanek, přijel do Kyjeva a že za námi zůstalo Srbsku jedenáct opěrných bodů a že Srbové dlouho nevydrží utíkat za našimi vojáky.

[I.14.5] Kromě toho naše manévry na Srbsku pokračují velice úspěšně a odchod našich vojsk, který jest fakticky jen přesunutím, vykládají si mnozí zcela jinak, než jak toho vyžaduje naprostá chladnokrevnost ve válce.

[I.14.6] "Náš pán je přísnej, a jak posledně se říkalo, že nám Srbsku natloukli, tak přišel celej vzteklej domů a sházel v kuchyni všechny talíře a chtěl i mně dát vejpověď."

[I.15] Všechny civilisty Srbsku spálit do posledního. Děti ubít bajonety!

[II.2] Tu odcházel domů a po jeho odchodu vždy někdo řekl: "Naši to zas někde Srbsku prosrati, že je vachmajstr takovej nemluva."

[II.2] Černožluté obzory počaly se zatahovat mraky revoluce. Na Srbsku, v Karpatech přecházely batalióny k nepříteli. 28. regiment, 11. regiment.

[II.2] ...jak nadporučík Kretschmann, který se vrátil ze Srbska s bolavou nohou (trkla ho kráva), vypravoval, jak se díval od štábu, ku kterému byl přidělen, na útok na srbské posice:

[II.3] Nešťastnou náhodou ještě nad tím nápisem byl jinej: ,My na vojnu nepůjdeme, my se na ni vyséreme,` a to bylo v roce 1912, když jsme měli jít do Srbska kvůli tomu konzulovi Procházkoví.

[II.3] „U pětasedmdesátýho regimentu,“ ozval se jeden muž z eskorty, „prochlastal hejtman celou plukovní kasu před válkou a musel kvitovat z vojny, a teď je zas hejtmanem, a jeden felák, kterej vokrad erár vo sukno na vejložky, bylo ho přes dvacet balíků, je dneska štábsfeldvéblem, a jeden infanterista byl nedávno v Srbsku zastřelenej, poněvadž sněd najednou svou konservu, kterou měl si nechat na tři dny.“

[II.3] Švejk seděl na odestlané posteli nadporučíkově a naproti němu seděl na stole sluha majora Wenzla. Major se opět vrátil k regimentu, když byla v Srbsku konstatována jeho úplná neschopnost na Drině.

[II.4] V Srbsku jsme pověsili dva jednoroční dobrovolníky od 10. kompanie a jednoho od 9. jsme zastřelili jako jehně.

[II.4] „Když jsem byl v Srbsku,“ řekl Vodička, „tak u naší brigády věšeli, kteří se přihlásili, čúžáky za cigarety.

[II.5] "Já z toho nemám moc velkou radost," důvěrně se ozval účetní šikovatel, "vypravoval štábsfeldvébl Hegner, že pan hejtman Ságner v Srbsku na počátku války chtěl někde u Černé Hory v horách se vyznamenat a hnal jednu kumpačku svého baťáčku za druhou na mašíngevéry do srbských štelungů, ačkoliv to byla úplné zbytečná věc a infantérie tam byla starýho kozla co platná, poněvadž Srby odtamtud z těch skal mohla dostat jen artilérie. Z celého bataliónu zbylo jen 80 mužů, pan hejtman Ságner sám dostal handšús, potom v nemocnici ještě úplavici, a zase se objevil v Budějovicích u regimentu a včera prý večer vypravoval v kasiné, jak se těší na front, že tam nechá celý maršbatalión, ale že něco dokáže a dostane signum laudis, za Srbsko že dostal nos, ale teť že bud padne s celým maršbataliónem, nebo bude jmenován obrstlajtnantem, ale maršbaták že musí zařvat. Já myslím, pane obrlajtnant, že se takové riziko týká i nás.

Also written:SrbskoczSerbiendeСрбијаsr

Literature

- Veltzés Internationaler Armee-Almanach, ,1914

- Operative Kriegsführung, 1914 Serbien - Kolubara, Belgrad,

- Den serbiske Hær, ,1914

- Das Lächeln der Henker, Anton Holzer,5.10.2008

- Zprávy z Turnova, ,24.11.1912

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

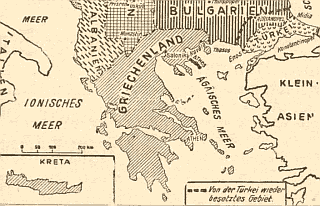

| Bulgaria |  | |||

| |||||

Bulgaria after the 2nd Balkan War

,23.8.1913

,1914

Bulgaria is mentioned during the conversation between Švejk and detective Bretschneider at U kalicha about Balkans.

Background

Bulgaria was a kingdom on the Balkans that was neutral during the first year of World War I. In September 1915 the country entered the war on the side of the Central Powers. Her main motive to join was to repair the damage after the defeat by Serbia in Second Balkan War. Bulgaria took part in the attack on Serbia in October 1915, the offensive that finally broke Serbia's resistance. Bulgaria was in 1914 slightly larger than today, she had to cede Thrace to Greece after the war.

Bulgaria was the first country amongst the Central Powers who withdrew from the war. After the Entente's breakthrough at the Thessaloniki front in September 1918 they capilutlated.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] A Švejk vyložil svůj názor na mezinárodní politiku Rakouska na Balkáně. Turci to prohráli v roce 1912 se Srbskem, Bulharskem a Řeckem. Chtěli, aby jim Rakousko pomohlo, a když se to nestalo, střelili Ferdinanda.

Also written:БългарияbgBulharskoczBulgariende

Literature

| Greece |  | |||

| |||||

Greece after the 2nd Balkan War

,30.8.1913

Greece is mentioned in the conversation at U kalicha between Švejk and detective Bretschneider about the Balkans. The former touched on their role in the First Balkan War.

Background

Greece was neutral at the start of the war but in November 1916 it joined the Entente, strongly influenced by prime minister Venizelos. Greece was at the time a kingdom ruled by the House of Glücksburg. The country was in 1914 slightly smaller than today, it acquired Thrace from Bulgaria in 1923.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] A Švejk vyložil svůj názor na mezinárodní politiku Rakouska na Balkáně. Turci to prohráli v roce 1912 se Srbskem, Bulharskem a Řeckem. Chtěli, aby jim Rakousko pomohlo, a když se to nestalo, střelili Ferdinanda.

Also written:ŘeckoczGriechenlandde Ελλάδαel

Literature

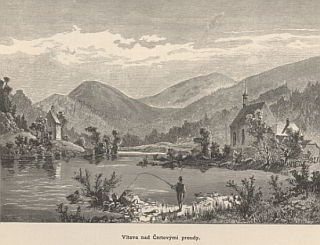

| Vltava |  | |||

| |||||

,1910

,28.6.1907

Vltava is mentioned 8 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Vltava is first mentioned in the anecdote about the man who jumped from the bridge in Krumlov. The river is mentioned several times later in the novel and Švejk must have crossed it twice during his anabasis in [II.2], without it being explicitly stated. The first crossing would have been between Květov and Vráž, the second on the train just before arriving in Budějovice.

Because Vltava flows through Prague, Švejk must have crossed it a few times in the first part of the novel. Across Karlův most he was escorted by two soldiers on the way from Hradčany to serve Feldkurat Katz. Before that Mrs. Müllerová pushed him across some bridge in a wheelchair for him to get to the draft board at Střelecký ostrov. He would also have had to cross the river when he went to Brusks to borrow money from captain Hauptmann Šnábl.

Background

Vltava is the longest river in Bohemia. From its sources in Šumava, it passes Český Krumlov, České Budějovice and Prague, before emptying into the Elbe by Mělník. The river's length is 430 km, and the catchment area is 28,090 km². In foreign languages the German name Moldau is frequently used.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Musel skočit v Krumlově s toho mostu do Vltavy a museli ho vytáhnout, museli ho křísit, museli z něho pumpovat vodu a von jim musel skonat v náručí lékaře, když mu dal nějakou injekci.“

[I.3] Soudní lékaři podívali se významně na sebe, nicméně jeden s nich dal ještě tuto otázku: „Neznáte nejvyšší hloubku v Tichém oceáně?“ „To prosím neznám,“ zněla odpověď, „ale myslím, že rozhodně bude větší než pod vyšehradskou skálou na Vltavě.“

[I.10.2] Projevoval mučednické touhy, žádaje, aby mu utrhl hlavu a hodil v pytli do Vltavy.

[I.10.3] Vy máte vilu na Zbraslavi. A můžete jezdit parníkem po Vltavě. Víte, co je to Vltava?“

[I.15] "Před dvěma léty, pane nadporučíku," řekl plukovník, "přál jste si být přeložen do Budějovic k 91. pluku. Víte, kde jsou Budějovice? Na Vltavě, ano, na Vltavě a vtéká tam Ohře nebo něco podobného.

[II.2] Zášť hrozná, nesmiřitelná, vendetta, krevní msta, dědící se z ročníku na ročník, provázená na obou stranách tradičními historkami, jak buď infanteristi naházeli dělostřelce do Vltavy, nebo opačně.

Also written:Moldaude

| Krumlov |  | |||

| |||||

Postcard from 1910

1915

Krumlov is mentioned in the anecdote about Bohuslav Ludvík and also a few times in Part Two. The miller Offiziersdiener Baloun, a central character in the latter part of the novel, comes from the area around Krumlov.

Background

Krumlov was until 1920 the name of Český Krumlov, a town not far from the Austrian border. The district of Krumlov was located in the recruitment area of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91, so Jaroslav Hašek would have known many fellow soldiers from there. See Ergänzungskommando.

The medieval structure of the town has been preserved and it is on the world heritage list of UNESCO. It has become a major tourist attraction.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Krumlov had 8,716 inhabitants of whom 1,295 (14 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Krumlov, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Krumlov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Krumlov were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 (Budweis) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 (Budweis). In 1913 the military presence was only one person.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Musel skočit v Krumlově s toho mostu do Vltavy a museli ho vytáhnout, museli ho křísit, museli z něho pumpovat vodu a von jim musel skonat v náručí lékaře, když mu dal nějakou injekci.“

[II.5] U dveří stál tlustý pěšák, zarostlý vousy jako Krakonoš. To byl Baloun, nový sluha nadporučíka, v civilu mlynář někde u Českého Krumlova.

Also written:Krumaude

Literature

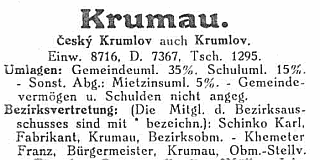

| Most v Krumlově |  | |||

| |||||

Most v Krumlově is mentioned in the anecdote about Bohuslav Ludvík who jumped from the bridge in Krumlov into the Vltava.

Background

Most v Krumlově (Bridge in Krumlov) was according to the story a bridge across the Vltava in Krumlov. The story does not reveal which one the author has in mind, but it is probably Lazebnický most in the centre which is the oldest and best known bridge there. In this mainly German-speaking town the bridge was at the time also called Baderbrücke.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Musel skočit v Krumlově s toho mostu do Vltavy a museli ho vytáhnout, museli ho křísit, museli z něho pumpovat vodu a von jim musel skonat v náručí lékaře, když mu dal nějakou injekci.“

Also written:Bridge in KrumlovenBrücke in KrumaudeBru i Krumlovno

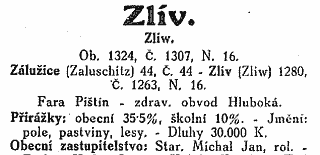

| Zliv |  | ||||

| ||||||

1915

Zliv is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk, told to detective Bretschneider. It was about a gamekeeper who was shot by poachers.

Background

Zliv is a village in South Bohemia, situated 10 km north west of Budějovice and 4 km west of Hluboká.

Hašek and Zliv

During the summer of 1896 (or 1897), Hašek's mother Kateřina took the children on a trip to the area around Protivín to visit relatives. Both his parents were from this area. They visited Zliv, Mydlovary, Hluboká, Budějovice, Putim, Skočice, Krč, Protivín, Ražice, and Vodňany. All of these places appear in The Good Soldier Švejk and some of them even in the short stories.

In the spring of 1915 Jaroslav Hašek reportedly appeared in Zliv again, now on an unauthorised "excursion" from the Budějovice garrison.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Zliv had 1,324 inhabitants of whom 1,307 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Hluboká, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Budějovice.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Zliv were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 (Budweis) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 (Budweis).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] To byl ve Zlivi u Hluboké před léty jeden hajný, měl takové ošklivé jméno Pinďour.

Credit: Radko Pytlík, Václav Menger, Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:ZliwReiner

Literature

| Hluboká |  | |||

| |||||

1915

Hluboká is mentioned in the same anecdote as Zliv, about the widow after the gamekeepers who turns up at the office of The prince at Hluboká to ask for advice.

At Gendarmeriestation Putim in [II.2] it is mentioned by Wachtmeister Flanderka when he informs Švejk how seriously he has got lost on his anabasis.

Later in the chapter Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek how he was given an injection by a cripple from Hluboká. This caused muscle rheumatism and he was admitted to hospital (Budějovická nemocnice).

Background

Hluboká is a small town in South Bohemia, 15 km north of Budějovice. It was one of the favourite haunts of German-Roman emperor Charles IV, who often visited when he resided in Budějovice. Nowadays Hluboká is best known for its Windsor-style chateau which until 1938 belonged to the House of Schwarzenberg.

Jaroslav Hašek visited Hluboká during his childhood (1896 or 1897), and probably also in 1915. See Zliv.

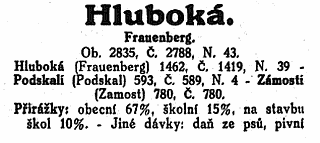

Demography

According to the 1910 census Hluboká had 2,835 inhabitants of whom 2,788 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Hluboká, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Budějovice.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Hluboká were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 (Budweis) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 (Budweis).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Byla až v kanceláři knížete pána na Hluboké a stěžovala si, že má s těmi hajnými trápení. Tak jí odporučili porybnýho Jareše z ražické bašty.

[II.2] Tak se podívejte, vojáku. Od nás na jih je Protivín. Od Protivína na jih je Hluboká a od ní jižně jsou České Budějovice.

[II.2] Až jsem se ti jednou ,U růže’ seznámil s jedním invalidou z Hluboké. Ten mně řekl, abych jednou v neděli k němu přišel na návštěvu, a na druhý den že budu mít nohy jako konve. Měl doma tu jehlu i stříkačku, a já jsem opravdu sotva došel z Hluboké domů. Neoklamala mne ta zlatá duše. Tak jsem konečně přece měl svůj svalový rheumatismus.

Also written:Frauenbergde

Literature

| Mydlovary |  | ||||

| ||||||

Mydlovary

,1959

1915

Josef Hašek (1843-1896)

,1959

Mydlovary is mentioned by Švejk in a story he tells detective Bretschneider about U kalicha, about the gamekeeper Pepík Šavel.

I [I.5] Mydlovary is mentioned again when Švejk tells an anecdote from when he did military training with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91.

Background

Mydlovary is a village in South Bohemia, 16 km north west of Budějovice and the birthplace of Josef Hašek, the father of Jaroslav Hašek. He was born in house number 8. The budding satirist visited Mydlovary during his childhood (1896 or 1897) and couldn't have been far away in 1915. See Zliv.

The fact that his father was born in Mydlovary is significant. This meant that Jaroslav Hašek had right of domicile here so he, just like his literary hero, was drafted into Infanterieregiment Nr. 91.

Early story

In 1911 Hašek wrote a story centred around Mydlovary: Vislingská aféra v Mydlovarech. It was first printed in Karikatury 7 March 1911 and soon after it appeared in Šípy in Chicago![a]

Demography

According to the 1910 census Mydlovary had 687 inhabitants of whom 680 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Hluboká, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Budějovice. In 1913 the community consisted of two villages. It had a church, a school and four pubs. The closest railway station and post office were found in Zliv. Zaháj was actually the largest of the two and the church was located here. Mayor at the time was Jan Kolář (relevant to the story about the scouts who were spanked with birch branches, see Okresní hejtmanství Budějovice).

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Mydlovary were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 (Budweis) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 (Budweis).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Zastřelili ho pytláci a zůstala po něm vdova s dvěma dítkami a vzala si za rok opět hajného, Pepíka Šavlovic z Mydlovar.

[I.5] „U skautů,“ zvolal Švejk. „o těch skautech rád slyším. Jednou v Mydlovarech u Zlivi, okres Hluboká, okresní hejtmanství České Budějovice, právě když jsme tam měli jednadevadesáté cvičení, udělali si sedláci z okolí hon na skauty v obecním lese, kteří se jim tam rozplemenili.

Also written:MydlowařReinerMydlowarde

Literature

- Obec Mydlovary,

- Genealogie Jaroslava Haška,

- Vislingská aféra v Mydlovarech, Jaroslav Hašek,22.4.1911 [a]

| a | Vislingská aféra v Mydlovarech | Jaroslav Hašek | 22.4.1911 |

| Ražická bašta |  | ||||

| ||||||

Photo from the site, 2010

Ražická bašta is mentioned by Švejk in an anecdote about the pond warden Jareš, no doubt inspired by the author's grandfather, Antonín Jareš. This connection appears again in chapters [I.14] and [II.2].

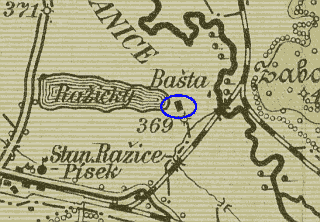

Background

Ražická bašta was a fishpond construction between Ražice and Putim that belonged to the noble Schwarzenberg family. The authors grandfather was pond warden here and Hašek wrote a few stories about him in Veselá Praha in 1908 called Historky z ražické bašty. The pond and barrier is still there but is no longer used for fish-farming. The pond wardens building is not there, but is still visible on an army-map from 1928.

The young Jaroslav Hašek visited the area in 1896 or 1897 together with his family. See Zliv.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Tak jí odporučili porybnýho Jareše z ražické bašty.

Credit: Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

- Nápověda a vysvětlivky,

- Dra Bělohlava Podrobné mapy zemí koruny České,

- Historky z ražické bašty, Jaroslav Hašek,1908

| Mexico |  | |||

| |||||

Světem letem, ,1896

Mexico Mexico is mentioned again in [II.2] when Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek tells Švejk about conditions in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91.

In [II.2] the country again appears, gain indirectly, through the term "the Mexixcan border". Here Fähnrich Dauerling is compared to Maxican bandits so the theme is no doubt the border with USA.

Background

Mexico was in 1914 a republic suffering turmoil after the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz had been overthrown in the revolution in 1911. In the period from 1864 to 1867 Maximiliano I. av Mexico was emperor, and it is in this context the country is mentioned in the novel.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Manželku Alžbětu mu propíchli pilníkem, potom se mu ztratil Jan Orth; bratra, císaře mexického, mu zastřelili v nějaké pevnosti u nějaké zdi.

[II.2] Nyní vám, kamaráde, musím něco říct o Dauerlingovi," pokračoval jednoroční dobrovolník, "o něm si vypravují rekruti u 11. kompanie tak, jako nějaká opuštěná babička na farmě v blízkostí mexických hranic bájí o nějakém slavném mexickém banditovi.

Also written:MexikoczMexikodeMéxicoes

Literature

| Cerro de las Campanas |  | |||

| |||||

Cerro de las Campanas is mentioned indirectly in the conversation between Švejk and detective Bretschneider where it is stated that the brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I. was executed at "some fortress by some wall".

Background

Cerro de las Campanas is a hill in Queretaro where císař Maximiliano I. was executed in 1867 after having lost the war against the republican rebels led by Benito Juárez.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] Manželku Alžbětu mu propíchli pilníkem, potom se mu ztratil Jan Orth; bratra, císaře mexického, mu zastřelili v nějaké pevnosti u nějaké zdi.

Literature

| Russia |  | |||

| |||||

The Russian Empire, 1914

Moscow

, 27.9.1912

Jaroslav Hašek v revolučním Rusku, ,1957

Russia is mentioned 22 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Russia is briefly touched upon during the conversation U kalicha about the political situation after the assassinations in Sarajevo. The next brief mention is in [I.14,1] when Feldkurat Katz has lost Švejk in a game of cards "as if he was a serf from Russia".

Russia is also a theme when Švejk is suspected of being a spy and is interrogated at Gendarmeriestation Putim. Wachtmeister Flanderka wants to know is tea is drunk in Russia and if the girls there are pretty. When the policeman ask Švejk why he wants to get to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 he answers that it is because he wants to go to the front. Flanderka immediately concludes that this is a very clever way to get back to Russia.

Later on in the novel the country is mentioned several times; it was after all Russia the main protagonists were sent to fight against. Russian citizens take part in the plot directly when Švejk is assigned to a transport of Russian prisoners in Chyrów. The author at least once adds fragments from his own experiences in Russia (see Dubno). The original advertising poster for the novel makes it clear that Jaroslav Hašek planned to stage the later part of the plot on Russian territory - the poster mentions the Russian civil war explicitly.

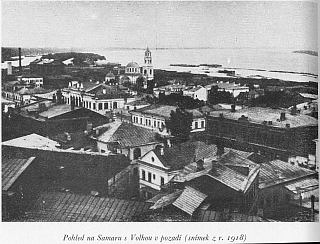

The following political and geographical entities of Russia (i.e. fully or partially located within its borders) are mentioned in the novel: Buryatia, Warsaw, Praga, Ukraine, Dubno, Tashkent, Zdolbunov, Poland, Sea of Azov, Caspian Sea, Kiev, Darnytsa, Franz Joseph Land, Komarów, Sevastopol, Don, Baikal, Kraśnik, Yerevan, Tbilisi, Caucasus, Moscow, Petrograd, Samara, Milatyn and Bubnów.

Background

Russia (rus. Россия) was in 1914 an empire ruled by the Romanov family and was far larger than the current Russian Federation. It included all of the later Soviet Union, all of Finland and the greater part of current Poland. The empire was at its largest in 1866 when it sold Alaska.

Russia's support to Serbia during the July crisis in 1914 is one of the prime reason why a regional conflict on the Balkans developed into a world war.

Russia were ill prepared for a prolonged war, serious supply problems and inept military leadership soon led to big losses. Still they managed to invade Galicia and Bukovina in 1914 and for a while they threatened to cross the Carpathians. On 2 May 1915 the Central Powers launched a successful offensive by Gorlice and Tarnów and 1915 turned out to be a disaster for Russland who had to withdraw from Poland and Galicia almost entirely. During that year the lack of equipment took its toll, and soldiers were sent into battle without firearms.

In 1916 the situation improved somewhat as the Brusilov-offensive inflicted such heavy losses on Austria-Hungary that a collapse threatened. German reinforcements however stabilised the front and Russia spent much of her diminishing strength on futile break-through attempts. The tsar dynasty was toppled in March 1917 but the new provisional government decided to continue the war. A final offensive was launched on 1 July 1917 but soon ground to a halt. During this fighting Czech volunteers (including Jaroslav Hašek) for the first time operated as a unit against the Dual Monarchy (Zborów 2 July). A German counter-offensive from 19 July led to a complete meltdown of a Russian army that already was badly affected by mass desertions and breakdown in discipline.

In the aftermath of the October Revolution (7 November 1917) a ceasefire was concluded, and the new Communist authorities had to accept harsh terms in the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk (signed 3 March 1918). All of the Baltics, Finland, Poland and Ukraine were ceded (Ukraina was recovered after the war). The subsequent civil war prolonged the suffering of the peoples of Russia with many years and in 1921 a massive hunger catastrophe hit some regions. The Russian defeat in the world war had fatal consequences; it paved the way for 70 years of Communist dictatorship, and at times extremely brutal.

Hašek in Russia

Jaroslav Hašek in Russia

Irkutsk. Hašek worked here in 1920.

Jaroslav Hašek served as a messenger in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 on the front against Russia from 11 July 1915, and at the end of the month the regiment took part in the bloody battle against the Russian 8th army by Sokal. On 27 August 1915 the regiment crossed the border and it was on Russian territory, by Chorupan north of Dubno, that he was captured on 24 September 1915.

After 9 months as prisoner Hašek was from July 1916[1] until March 1918 a volunteer in the Legions in Russia, and therefore he formally became a Russian soldier. During this period he functioned both as a reporter and as recruiter amongst Czech priosners of war. His base was Kiev but he also spent long periods at the front by the river Stochod in 1916. Disciplinary problems led to his expulsion from Kiev in May 1917 and he was sent to the area by Sarny as an ordinary soldier. From there he was, together with what was now called the Czechoslovak Brigade transferred to occupied Austrian territory where they took part in the battle by Zborów (ru/cz. Zborov, ukr. Zboriv) on 2 July 1917. He took part in the withdrawal from Tarnopol (ukr. Ternopil) later that month and for his efforts he was decorated with the Russian Cross of Saint George, 4th class.

After breaking with the Legions in April 1918 he became of journalist, agitator and recruiter for the Czech communists, later directly for the Bolsheviks - positions he held until he was sent back to his homeland as agitator at the end of 1920. He had learnt Russian already as a youngster and reportedly mastered the language very well, and by his return he had adapted to the degree that even his novel contains “russianisms”.

During his 5 year stay in Russia his travels covered extensive areas, mostly in Ukraine, in the Volga region and in Siberia. On 15 May 1920 he married a Russian woman, Alexandra Lvova. She followed him back to Prague later that year. In his story I vyklepal prach z obuvi své... Hašek informs that he left Russia 4 December 1920 in Narva.

Places in Russia where Jaroslav Hašek had prolonged stays were: Totskoye (prisoner's camp), Kiev, Moscow, Samara, Bugulma, Ufa and Irkutsk. He obviously had shorter stays in many other places, mainly along the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Vy myslíte, že to císař pán takhle nechá bejt? To ho málo znáte. Vojna s Turky musí být. Zabili jste mně strejčka, tak tady máte přes držku. Válka jest jistá. Srbsko a Rusko nám pomůže v té válce. Bude se to řezat!“

[I.14.1] Polní karát prodal Švejka nadporučíkovi Lukášovi, čili lépe řečeno, prohrál ho v kartách. Tak dřív prodávali na Rusi nevolníky.

[I.14.5] Francie, Anglie i Rusko jsou příliš slabé proti rakousko-turecko-německé žule.

[I.14.5] Pro chmel je nyní ztracena Francie, Anglie, Rusko i Balkán.

[II.2] Strážmistr podíval se na Švejka a začal: "Pravda, že v Rusku se pije mnoho čaje? Mají tam také rum?"

[II.2] A otázal se důvěrně nakláněje se k Švejkovi: "Jsou v Rusku hezké holky?"

[II.2] "A já se zas pamatuji," prohlásil, "že oni říkali, že jsme proti Rusku kratinové, a že řvali před tou naší bábou ,Ať žije Rusko!`"

[II.4] Jen pořád rovně za nosem do Ruska a z radosti vypalte do vzduchu všechny patrony

Also written:RuskoczRusslanddeРоссияru

| 1. | Hašek was enrolled in the Czecho-Slovak Brigade 29 June 1916, and 4 April 1918 he announced in writing that he left the Legions. |

Literature

- Rusko, ,1904

- Russia, ,1911

- Veltzés Internationaler Armee-Almanach, ,1914

- Russian Civil War, Alexandre Sumpf

- Гашек в Иркутске, ,28.6.2017

- Velitelem města Bugulmy, ,1966

- Upomínky na můj vojenský život, ,2020 [a]

| a | Upomínky na můj vojenský život | 2020 |

| Turkey |  | |||

| |||||

,30.10.1914

, 1915

,31.10.1918

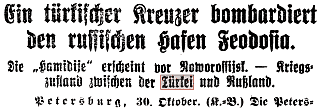

Turkey is mentioned 4 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Turkey is theme of the conversation at U kalicha about the political situation after the assassination in Sarajevo. Švejk blames the Turks for the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The country is mentioned again in [I.14] during Oberleutnant Lukáš' long lecture to hop trader Wendler about the war situation. This conversation also mention a number of distinguished Ottoman politicians and officers. Amongst them are the Sultan, Enver Paşa, Cevat Paşa, Hali Bey, and Ali Bey. Also mentioned are Constantinople, Dardanelles and Turkish Parliament.

Background

Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) was a state that existed until 1922 and was succeeded by modern Turkey. The area was still in 1914 far larger than that of the current republic and included great parts of the Middle East. It was a multi-ethnic empire, consisting of Turks, Arabs, Armenians, Albanians, Greeks, Jews etc. The capital was Constantinople.

The first world war

From 29 October 1914 the Ottoman Empire entered the war as one of the Central Powers. It started with an attack on Russian Black Sea ports, and a few days later Russia declared war, and soon after Turkey was also at war with England and France.

Turkey fought on several fronts: against Russia in Caucasus, against the British in Egypt and Mesopotamia, against the Russians and British in Persia. In 1915 the allied attempt to force the Dardanelles opened another front, although short-lived. Moreover the empire had to fight uprisings on the Arab Peninsula and elsewhere.

Several high ranking Germans served in the Ottoman armed forces, both as commanders and advisors. Amongst them were Marschall Liman von Sanders, Goltz Paşa and Usedom Paşa. A lasting shadow over the final years of the Ottoman Empire was cast by the genocide of Armenians in 1915.

Turkey had only minor military success in the war, but a major exception was the defence of the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915. By the end of 1917 Allied forces stood deep in Ottoman territory: Palestine and also in Mesopotamia.

After Bulgaria pulled out of the war in September 1918 Turkey's position became untenable and the armistice was signed on 30 October 1918. The defeat in the World War meant the end of the empire and the loss of all her Arabic possessions. The core Turkish areas of the empire was transformed into a republic and was to become the pillar of modern Turkey.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Může být,“ pokračoval v líčení budoucnosti Rakouska, „že nás v případě války s Tureckem Němci napadnou, poněvadž Němci a Turci drží dohromady. Jsou to takový potvory, že jim není v světě rovno. Můžeme se však spojit s Francií, která má od 71. roku spadeno na Německo. A už to půjde. Válka bude, víc vám neřeknu.“

[I.14.5] „A co Turecko?“ otázal se obchodník s chmelem, uvažuje přitom, jak začít, aby se dostal k jádru věci, pro kterou přijel.

Also written:TureckoczTürkeideTyrkiyetr

Literature

| France |  | ||||

| ||||||

France is mentioned 8 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

France is mentioned in the conversation between Švejk and detective Bretschneider at U kalicha about the political situation after the assassinations in Sarajevo. In this case the theme is the Franco-German war of 1870-71. Many French people are mentioned in the novel: Napoléon, Victor Hugo, Papin and Rabelais are amongst them.

In the conversation between hop trader Wendler and Oberleutnant Lukáš in [I.14] French places are mentioned, all along the front in northern France. The officer also mentions the country itself and Wendler mentions these places along the front: Combres, Woëvre, Marchéville and Vosges. The rivers Meuse and Moselle that partly flow through the country are mentioned in the same sequence. French culinary connections appear through the terms Cognac and Bordeaux.

Background

France was in 1914 a democratic republic of nearly 40 million inhabitants and also ruled over a large colonial empire, mainly in Africa.

France was one of the main participants in World War I. Germany declared war on her on 3 August 1914, on 11 August France declared war on Austria-Hungary. Already from 1894 France had signed a military alliance with Russia, and from 1907 England joined them in the so-called Triple Entente, albeit with fewer military obligations. The rising power of Germany was the reason why these former rival powers now joined forces.

Throughout the war nearly the whole the Western Front cut through northern France, and the area where the fighting took place was devastated. French war casualties totalled 1.7 million dead, and out of these 1.4 million were soldiers. The losses made up more than 4 per cent of the population. France was close to collapse both in 1914 and 1918 when the German army reached the river Marne, north-east of Paris.

France was the first state to recognize the Czech and Slovak claim for an independent state, and the Czechoslovak National Council was seated in Paris from 1916. On 7 February 1918 the Czechoslovak Army Corps in Russia formally became part of the French army and were to be transferred to the Western Front. See České legie. This was a decision Jaroslav Hašek disagreed with and it was the main reason why he left the army corps two months later.

After the Treaty of Versailles France was given back Alsace and Lorraine, provinces that had been ceded to Germany in 1871.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Může být,“ pokračoval v líčení budoucnosti Rakouska, „že nás v případě války s Tureckem Němci napadnou, poněvadž Němci a Turci drží dohromady. Jsou to takový potvory, že jim není v světě rovno. Můžeme se však spojit s Francií, která má od 71. roku spadeno na Německo. A už to půjde. Válka bude, víc vám neřeknu.“

[I.14.5] Francie, Anglie i Rusko jsou příliš slabé proti rakousko-turecko-německé žule.

[I.14.5] Stejně Francouzům hrozí v nejkratší době ztráta celé východní Francie a vtržení německého vojska do Paříže.

[I.14.5] Pro chmel je nyní ztracena Francie, Anglie, Rusko i Balkán.

Also written:FrancieczFrankreichdeLa Francefr

Literature

- "Le Brave Soldat Chvéïk" de Jaroslav Hasek, ,16.4.1932

| Germany |  | |||

| |||||

Hašek describing his arrival in Swinemünde

,1.2.1921

Germany is mentioned 8 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Germany is first mentioned at the conversation at U kalicha about the political situation after the assassinations of Sarajevo. The country then appears repeatedly throughout the novel, particularly during the march battalion's journey to the front. Towards the end of the novel Švejk even meets German soldiers. The author notes how well they are provided for compared with their allies from Austria-Hungary.

Many German nationals are mentioned; amongst them Emperor Wilhelm II. and Hindenburg. A number of German cities also appear: amongst them Berlin, Hamburg and Leipzig. It also revealed that Švejk once visited Bremen, and this is as far as we know the only time he ever ventured beyond the borders of Austria-Hungary. When forging of the pedigree of Fox, Švejk mentions the name of several institutions in Germany related to dog-breeding (see Nuremberg). A few places in Elsass (Alsace) are mentioned in the conversation between Oberleutnant Lukáš and hop trader Wendler, amongst them Mühlhausen (Mulhouse). During his famous dream Kadett Biegler refers to some smaller places in his account of the battle by Leipzig in 1813 (see Wachau). The last time we hear about Germans is when Švejk arrives at Żółtańce where he has to witness that the Germans get draught beer, a luxury he and his comrades can only dream of. We are also told that men from his regiment have been in a brawl with the Bavarians at the town square.

Background

Germany was in 1914 a constitutional monarchy with the emperor as head of state, officially named Das Deutsche Kaiserreich. She entered the war as an ally of Austria-Hungary 1 August 1914 when she declared war on Russia. The two Central European powers had been allies since 1879, and Germany’s explicit support was one of the reasons that the Dual Monarchy risked to "teach Serbia a lesson" in 1914. Two days later the two-front war became a reality through the French declaration of war. The German attack on Belgium on 4 August 1914 contributed to landing an even more powerful enemy: England and the vast British Empire.

In 1914 Germany possessed the strongest army in the world but despite her military might she could ill sustain a prolonged conflict where the adversaries were superior in industrial resources, manpower and not the least in raw materials. The British naval superiority was also a determining factor; the blockade was soon to lead to serious shortages and later outright destitution.

From 1915 onwards Germany repeatedly had to act to help its weaker ally Austria-Hungary. At the section of the front in Galicia and Volhynia where Jaroslav Hašek and his Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 took part in 1915, troops of the Dual Monarchy were supported by German units and three of these are mentioned in the novel (see Posen, Hanover and Brandenburg). Although Germany plays a peripheral role in the novel, it appears considerably more often in the stories Jaroslav Hašek wrote when serving in the Czech exile organisations in Russia in 1916 and 1917. These mainly served propaganda purposes against the Central Powers and Germany is, as one would expect, portrayed in a negative way. Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí and the story Gott strafe England are typical examples. In the autumn of 1916 the author spent much of his time at the front by the river Stochod (now Stochid), where they faced the German army.

The defeat in 1918 meant the end of imperial Germany and the Versailles peace treaty of 1919 forced Germany to cede large areas; mostly to Poland and France but also smaller areas to Denmark, Belgium and Czechoslovakia. Germany suffered more than 2 million fallen and in addition a few hundred thousand civilians died due to hunger and shortages. The economic, social and political consequences of the of defeat were fatal and to a large extent it paved the way for Nazism and the even more disastrous Second World War.

Jaroslav Hašek and Germany

Serving the Bolsheviks in 1919 and 1920, Jaroslav Hašek worked closely with German internationalists (communists), recruited from prisoner of war camps. There is every indication that he closely followed the revolutionary movement in Germany and at this time he even wrote a poem in German. It was called Spartaks Helden and was a homage to the murdered communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. The poem is however dangerously close plagiarism, borrowing heavily from Erich Mühsam's Generalstreik - Marsch.

Jaroslav Hašek visited Germany in the summer of 1904, probably Bavaria only. Here he at least must have spent a few weeks and he wrote a handful of short stories about this trip. He knew German well although quotes from the novel indicate certain shortcomings (in the German translation numerous German-language quotes are corrected). In another story he indicates that he visited Dresden, which is also very probable.

On 8 December 1920 Hašek again set foot on German soil. He and his wife Russian wife Alexandra arrived from Tallinn to Swinemünde (now Swinoujście). They were returning from Russia as repatriates and took the train onwards from Stettin (now Szczecin) in the evening on 9 December. The stay on German soil was brief, probably less than 48 hours, with a likely change of trains in Berlin before they travelled onwards to Pardubice where they arrived in the evening of the "second day” (probably 10 December). Hašek described his arrival in Germany in this story[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.1] „Může být,“ pokračoval v líčení budoucnosti Rakouska, „že nás v případě války s Tureckem Němci napadnou, poněvadž Němci a Turci drží dohromady. Jsou to takový potvory, že jim není v světě rovno. Můžeme se však spojit s Francií, která má od 71. roku spadeno na Německo. A už to půjde. Válka bude, víc vám neřeknu.“

[I.14.3] A vopravdu, lidi hned byli rádi, že to tak dobře dopadlo, že mají doma čistokrevný zvíře, a že jsem jim moh nabídnout třebas vršovickýho špice za jezevčíka, a voni se jen divili, proč takovej vzácnej pes, kerej je až z Německa, je chlupatej a nemá křivý nohy.

[I.15] Nebyl o nic horší než německý básník Vierordt, který uveřejnil za války verše, aby Německo nenávidělo a zabíjelo s železnou duší milióny francouzských ďáblů..

[I.15] Potom si vypravovali o tom, že se obilí od nás vozí do Německa, němečtí vojáci že dostávají cigarety a čokoládu.

Also written:NěmeckoczDeutschlandde

Literature

- Přátelský zápas mezi Tillingen a Höchstädt, Jaroslav Hašek,10.7.1921

- I vyklepal prach z obuvi své... VI., Jaroslav Hašek,1.2.1921 [a]

| a | I vyklepal prach z obuvi své... VI. | Jaroslav Hašek | 1.2.1921 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |