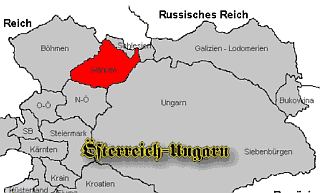

Švejk's journey on a of Austria-Hungary from 1914, showing the military districts of k.u.k. Heer. The entire plot of The Good Soldier Švejk is set on the territory of the former Dual Monarchy.

The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (mostly known as The Good Soldier Švejk) by Jaroslav Hašek is a novel that contains a wealth of geographical references - either directly through the plot, in dialogues or in the author's narrative. Hašek was himself unusually well travelled and had a photographic memory of geographical (and other) details. It is evident that he put a lot of emphasis on geography: Eight of the 27 chapter headlines in the novel contain geographical names.

This web site will in due course contain a full overview of all the geographical references in the novel; from Prague in the introduction to Klimontów in the unfinished Part Four. Continents, states (also defunct), cities, market squares, city gates, regions, districts, towns, villages, mountains, mountain passes, oceans, lakes, rivers, caves, channels, islands, streets, parks and bridges are included.

The list is sorted according to the order in which the names appear in the novel. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's translation from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by these examples: Sanok a location where the plot takes place, Dubno mentioned in the narrative, Zagreb part of a dialogue, and Pakoměřice mentioned in an anecdote.

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60) II. At the front

II. At the front  2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (38)

1. Across Magyaria (38) 2. In Budapest (38)

2. In Budapest (38) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50) 4. Forward March! (42)

4. Forward March! (42)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

10. Švejk as a military servant to the field chaplain | |||

| Karlův most |  | ||||

| ||||||

Karlův most seen eastwards towards Staré Město, around 1914.

Karlův most is part of the plot in a single brief sentence when Švejk is escorted to Feldkurat Katz: "they went across the Charles Bridge in absolute silence". The bridge has previously been mentioned in [I.4] where Švejk during his stay in the madhouse mentions some baths near the bridge.

Background

Karlův most (Charles Bridge) is the oldest and most famous bridge in Prague and the second oldest bridge in Czechia after the one in Písek. It connects the Malá Strana and Staré město. As a landmark and tourist attraction it belongs to the most famous in the country.

Construction was started in 1357 under Charles IV's reign and the bridge is named after him. Around 1700 it was given the shape known today and the barock statues were erected in this period. The bridge has repeatedly been threatened by high water levels but escaped the great flood of 2002 without damage, but in 1890 it was partly destroyed.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Šli přes Karlův most za naprostého mlčení. V Karlově ulici promluvil opět malý tlustý na Švejka: „Nevíš, proč tě vedem k polnímu kurátovi?“

Also written:Charles BridgeenKarlsbrückedeKarlsbruano

Literature

| Karlova ulice |  | ||||

| ||||||

Průhled Karlovou ulicí od křižovatky s Liliovou k východu. Vpravo dům čp. 180 ("U Modré štiky"). Uprostřed v pozadí dům čp. 175 na Starém Městě.

Karlova ulice is the scene of the plot as Švejk is led through Karlova ulice on the way to Feldkurat Katz in Karlín. The guards ask Švejk why they were taking him to the chaplain. "Because I'm going to be hanged tomorrow", was the answer. Thus he got their sympathy and they ended up in merry company in Na Kuklíku.

Background

Karlova ulice is a street in Staré město (Old Town) in Prague. It leads from Karlův most to Staroměstské náměstí.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Šli přes Karlův most za naprostého mlčení. V Karlově ulici promluvil opět malý tlustý na Švejka: „Nevíš, proč tě vedem k polnímu kurátovi?“ „Ke zpovědi,“ řekl ledabyle Švejk, „zítra mě budou věšet. To se vždycky tak dělá a říká se tomu duchovní outěcha."

Also written:Karlstrassede

Literature

| Josefov |  | |||

| |||||

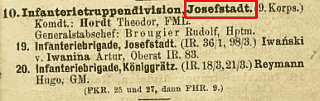

Seidels kleines Armeeschema, August 1914.

Josefov is mentioned by Švejk's fat and optimistic escort, on the way to Feldkurat Katz. He came from the area around this town.

Later in the chapter the name appears again in during Švejk's final visit to U kalicha. Here met meets a locksmith from Smíchov who thinks the soldier is a deserter, tells him that his son has run away from the army, and now stays with his grandmother at Jasenná by Josefov.

Background

Josefov is a fortress and former garrison town in eastern Bohemia, near the border with Poland. It is now part of Jaroměř.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Josefov had 5,438 inhabitants of whom 4,033 (74 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Jaroměř, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Dvůr Králové nad Labem.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Josefov were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 18 (Königgrätz) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 11 (Jičin). A total of 2612 people were employed by the garrison and this explains the high the number of Germans speakers in this very Czech part of Bohemia.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Asis se narodil na nešťastné planetě,“ znalecky a se soucitem poznamenal malinký, „u nás v Jasenné u Josefova ještě za pruský války pověsili také tak jednoho. Přišli pro něho, nic mu neřekli a v Josefově ho pověsili.“

[I.10.4] Na ulici se domluvil se Švejkem, kterého též považoval dle odporučení hostinské Palivcové za dezentéra. Sdělil mu, že má syna, který také utekl z vojny a je u babičky v Jasenné u Josefova.

Also written:Josefstadtde

Literature

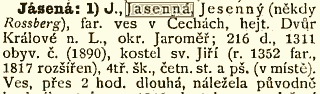

| Jasenná |  | |||

| |||||

, 1898

Jasenná (also Jasená) was the home village of the fat and optimistic guard who escorted Švejk to Feldkurat Katz.

In [I.10] the name appears again in during Švejk's final visit to U kalicha. Here met meets a locksmith from Smíchov who thinks the soldier is a deserter, tells him that his son has run away from the army, and now stays with his grandmother at Jasenná by Josefov.

Background

Jasenná is a village located 8 km south east of Jaroměř in the district of Královéhradecko.

Hašek in Jasenná

In August 1914 Jaroslav Hašek visited his friend Václav Hrnčíř here, no doubt an inspiration for this reference in the novel. The stay lasted for about a month[a]. The theme also appears in the story Nebezpečný pracovník that was printed in Humoristické listy on 28 August 1914[b].

Demography

According to the 1910 census Jasenná had 1,354 inhabitants of whom 1,353 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Jaroměř, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Dvůr Králové nad Labem.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Jasenná were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 18 (Königgrätz) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 11 (Jičin).

Radko Pytlík, Toulavé house, kap. Sarajevo

V Praze začíná to být pro rebela a bývalého anarchistu nebezpečné. Kamarádi radí, aby zmizel z Prahy. Hašek odjíždí hned po vyhlášení války v létě 1914 k příteli Václavu Hrnčířovi do Jasené u Jaroměře. Příhody, které zažil na žních u Samků (jejichž Aninka byla Hrnčířovou nevěstou), popsal v povídce Nebezpečný pracovník. Zdržel se zde asi měsíc.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Asis se narodil na nešťastné planetě,“ znalecky a se soucitem poznamenal malinký, „u nás v Jasenné u Josefova ještě za pruský války pověsili také tak jednoho. Přišli pro něho, nic mu neřekli a v Josefově ho pověsili.“

[I.10.4] Na ulici se domluvil se Švejkem, kterého též považoval dle odporučení hostinské Palivcové za dezentéra. Sdělil mu, že má syna, který také utekl z vojny a je u babičky v Jasenné u Josefova.

Credit: Radko Pytlík

Also written:Jasenade

Literature

- Toulavé house, ,1971 [a]

- Nebezpečný pracovník, ,28.8.1914 [b]

- Historie,

| a | Toulavé house | 1971 | |

| b | Nebezpečný pracovník | 28.8.1914 |

| Prussia |  | |||

| |||||

Prussia is first mentioned in the novel in connection with the "Prussian War", a colloquial term for the so-called German war of 1866. This war is the theme of the conversation between Švejk and his escort on the way from Hradčany to Feldkurat Katz.

In [I.11] the country is referred to directly, now in connection with the author's description of religious rituals at executions.

Background

Prussia was until 1947 a geographical and political unit, and had been a separate kingdom from 1701 til 1871. Prussia was the leading state in Germany until 1945. The area is today split between Germany, Poland and Russia. The capital was Berlin.

The Prussian War, more commonly known as the German war, was a month-long armed conflict between Prussia and Italy on one side and Austria and their mainly south German allies on the other. The war took place in 1866 and ended quickly with a Prussian victory. The deciding battle was fought by Hradec Králové (Königgrätz) on 3 July 1866. The Austrian defeat had far-reaching political repercussions. Hungary exploited the defeat to demand parity within the monarchy, thus the war led directly to the creation of Austria-Hungary.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Asis se narodil na nešťastné planetě,“ znalecky a se soucitem poznamenal malinký, „u nás v Jasenné u Josefova ještě za pruský války pověsili také tak jednoho. Přišli pro něho, nic mu neřekli a v Josefově ho pověsili.“

[I.11] V Prusku vodil pastor ubožáka pod sekyru...

Also written:PruskoczPreußende

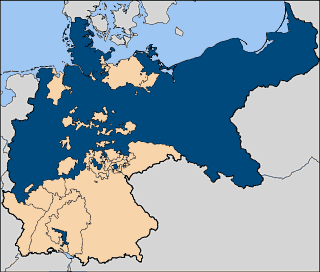

| Královéhradecko |  | |||

| |||||

Hradec Králové, 2010.

,5.12.1915

Královéhradecko is the home region of the two soldiers who escorted Švejk from Hradčany to Feldkurat Katz.

Background

Královéhradecko is now an administrative region in Bohemia that borders Poland. It is named after the main city of Hradec Králové, one of the 10 most populous cities in Czechia.

Newspaper clips from World War I indicate that the term okres Hradec Králové is meant, an area that doesn't include Jasenná og Josefov where the author indicates that Švejk's escort is from. The administrative unit was hejtmanství Hradec Králové that counted 74,125 inhabitants (1913) and also the smaller okres with 55,521 inhabitants, of which the city itself counted 11,065.

It is however unlikely that the author got this is wrong, solid as his knowledge of geography was. Královéhradecko was the name of a former kraj, a long established administrative unit that was abolished in 1862 but obviously lingered as a term for many years. The kraj (Kreis) was a much larger unit than hejtmanství and it did include Jasenná. In 1862 there were a total of 13 kraj in Bohemia.

Ottův slovník naučný also refers to Hradec Králové as a "kraj capital" so the word was still in use even in formal literature. As a judicial division the term was still in use, as in krajský soud (Kreisgericht). In 1920 the kraj resurfaced as an administrative unit so Královéhradecko existed also formally when the novel was written.

The city is in history best known for the battle between Austria og Prussia i 1866, abroad known as the battle of Königgrätz. The Austrian defeat was exploited by Hungary to demand parity within the Habsburg monarchy. This so-called Ausgleich led directly to the creation of Austria-Hungary in 1867.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

Similarly the region is mentioned in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí but also here only in passing.[1]

Někdy se dával do hovoru se stařečkem odněkud z Královéhradecka, který byl odsouzen na čtyry roky, poněvadž při soupisu obilí přinesl otýpku sena a hodil ji komisaři pod nohy se slovy: "A to vemte také s sebou, ať má císař pán co jíst!"

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Zakouřili si všichni a průvodčí počali sdělovat jemu o svých rodinách na Královéhradecku, o ženách, dětech, o kousku políčka, o jedné krávě.

Also written:Region Königgrätzde

Literature

- Válečná vystava v Praze, ,5.12.1915

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Pankrác |  | ||||

| ||||||

Vilímek's Führer durch Prag und die Ausstellung, 1891

Pankrác is introduced already by pubkeeper Palivec in the first chapter, but here he obviously refers to Věznice Pankrác. This is also the case in [I.3] where the unfortunate lathe operator who broke into Podolský kostelík was imprisoned and later died.

The place itself is introduced through the popular song "Na Pankráci" when the author and his entourage enter Kuklík.

The fourth time Pankrác is mentioned is when the author informs that one of Švejk's predecessors as a servant of Oberleutnant Lukáš had sold his master's s dog to the knacker at Pankrác (see Pohodnice Pankrác) and even pocketed the proceeds.

Background

Pankrác is a Prague district, named after Saint Pancras, located in the upper part of Nusle. The district is best known for its prison and was also an important industrial area. It is now (2015) a business and administrative district where many multinational firms have their Czech headquarters. See also Věznice Pankrác.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Pankrác had 8,119 inhabitants of whom 7,921 (97 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Nusle, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Královské Vinohrady. Pankrác was part of Nusle town until 1922 when they became part of Prague. It belonged to the Nusle Catholic parish but had its own post office.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Pankrác were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Na Pankráci, tam na tom vršíčku, stojí pěkné stromořadí...

[I.14.3] Kanárka mořili hladem, jeden sluha angorské kočce vyrazil jedno oko, stájový pinč byl od nich práskán na potkání a nakonec jeden z předchůdců Švejka odvedl chudáka na Pankrác k pohodnému, kde ho dal utratit, nelituje dát ze své kapsy deset korun.

Literature

| Florenc |  | |||||

| |||||||

,23.3.1915

Florenc is where Švejk and his two by now sozzled escort dropped by a café, actually behind Florenc. This was their last stop on the way to Feldkurat Katz in Karlín. The fat guard sold his silver watch here so he could amuse himself further.

Background

Florenc is a small area of Prague, east of the centre towards Karlín. Today it is a busy traffic intersection and Prague's enormous coach station is also located here. The entire area was inundated during the great flood in august 2002.

The name Florenc appeared in the 15th century, believed to be named after Italian workers who settled here. As Florenc was not an administrative unit the borders are only loosely defined. The quarter straddles Praha II. and Karlín and the street Na Florenci defines it approximately. The best known building was (and still is) Museum města Prahy (Prague City Museum).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Stavili se za Florencí v malé kavárničce, kde tlustý prodal své stříbrné hodinky, aby se mohli ještě dále veselit.

| Karlín |  | |||

| |||||

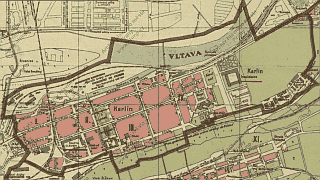

Karlín 1909

Karlín is mentioned 13 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Karlín was the town where Feldkurat Katz lived, more precisely in Královská třída (now Sokolovská třída). We must assume that his office was near Ferdinandova kasárna. Part of the action in [I.10-13] takes place in Karlín, mostly in the flat of Katz. The town itself and places within it are mentioned numerous times later in the novel (through anecdotes).

Background

Karlín is a district in Prague that borders Vltava, Praha II., Žižkov and Libeň. It was until 1922 a separate town.

Ferdinandova kasárna (also Karlínska kasárna) was located here and served as heaquarters of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 until August 1914. See Regimentskanzlei Budweis. Karlín was an industrial town where large plants like Daňkovka were located. Another important institution in town was Invalidovna. During the world war it served as a military hospital, and it was until 2013 the site of VÚA (The Central Military Archive).

Karlín hejtmanství had a population of 69,184 where the largest communities apart from the town itself were Troja, Kobylisy and Vysočany.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Karlín had 24,230 inhabitants of whom 20,694 (85 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Karlín, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Karlín.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Karlín were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag). The town was in 1910 home to 1,773 military personnel, amongst these distribution between Czech and German speakers was fairly equal.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Na úsměvy diváků odpovídal Švejk měkkým úsměvem, teplem a něhou svých dobráckých očí. A tak šli do Karlína, do bytu polního kuráta. První promluvil na Švejka malý tlustý. Byli právě na Malé Straně dole pod podloubím. „Odkud jseš?“ otázal se malý tlustý. „Z Prahy.“

[II.3] Potom ještě řekl Paroubkovi, že je huncút a šaščínská bestie, tak ho milej Paroubek chyt, votlouk mu jeho pastě na myši a dráty vo hlavu a vyhodil ho ven a mlátil ho po ulici tyčí na stahování rolety až dolů na Invalidovnu a hnal ho, jak byl zdivočelej, přes Invalidovnu v Karlíně až nahoru na Žižkov, vodtud přes Židovský pece do Malešic, kde vo něj konečně tyč přerazil, takže se moh vrátit nazpátek do Libně.

[II.5] Servus, kolego. Jak se jmenuji? Švejk. A ty? Braun. Nemáš příbuznýho nějakýho Brauna v Pobřežní třídě v Karlíně, kloboučníka?

Also written:Karolinenthalde

Literature

- Karlínské listy, ,1903-1912

- Karlin - Karolinenthal: Eine kleine Stadtgeschichte, ,2007

| Královská třída |  | ||||

| ||||||

Průhled Královskou ulicí (dnes Sokolovská) od křižovatky s Vítkovou ulicí k východu ke Karlínskému náměstí. Zleva domy čp. 439, čp. 5 (U Červené hvězdy) v Karlíně.

Královská třída was the street in Karlín where Feldkurat Katz lived. The exact address is not known, but the field chaplain's flat was probably near Ferdinandova kasárna (where he may have served).

Background

Královská třída (now Sokolovská) is a long avenue in Prague that connects Praha II., Karlín, Libeň and Vysočany.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Švejk je neustále musel upozorňovat, když šel naproti důstojník nebo nějaká šarže. Po nadlidském úsilí a namáhání podařilo se Švejkovi přivléct je k domu v Královské třídě, kde bydlel polní kurát.

Also written:Königstraßede

Literature

| Vatican |  | |||

| |||||

Vatican is mentioned by Feldkurat Katz in when he talks drunk drivel in the cab home from Oberleutnant Helmich. He claims that the Vatican shows an interest in him.

Background

Vatican is the centre of the Roman-Catholic Church, and the name of the associated micro-state located in the middle of Rome. Here it is probably meant The Holy See as an institution rather than the Vatican State. Pope from 1904 until 20 August 1914 was Pius X, who was succeeded by Benedict XV. See also The Pope.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Já byl u arcibiskupa,“ hulákal, drže se vrat v průjezdu. „Vatikán se o mne zajímá, rozumíte?“

Also written:Vatikáncz

Literature

| Domažlice |  | |||

| |||||

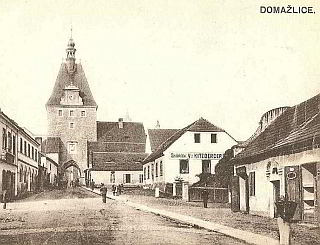

Domažlice is mentioned in a song Feldkurat Katz attempts to sing when in an inebriated state in the back from Oberleutnant Helmich. The town is mentioned in several anecdotes later in the novel, for instance by Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in the story about the editor that invented new animals. One of Hašek's closest friend, Hájek, appears in some of these stories.

Background

Domažlice is a town with around 11,000 inhabitants in Plzeňský kraj in western Bohemia, less than 20 km from the Bavarian border. Jaroslav Hašek visited the town in 1904 on the way back from his wanderings in Bavaria. He stayed with his friend Hájek and his family.

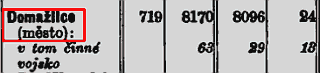

Demography

According to the 1910 census Domažlice had 8,170 inhabitants of whom 8,096 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Domažlice, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Domažlice.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Domažlice were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 35 (Pilsen) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 (Pilsen). The census of 1910 reveals a small military presence. To judge by Schematismus they seem to have been involved in horse-breeding.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Jednu chvíli se zdálo, že drkotáním drožky o dlažbu přichází k rozumu. To se posadil rovně a začal zpívat nějaký úryvek z neznámé písně. Může být též, že to byla jeho fantasie:

Vzpomínám na zlaté časy, když mne houpal na klíně, bydleli jsme toho času u Domažlic v Merklíně.

Also written:Tausde

Literature

- Historie města Domažlice, ,2.2.2002

- Velký den, Jaroslav Hašek,9.10.1904

- Výprava Jana Hučky z Pašešnice, Jaroslav Hašek,12.11.1905

| Merklín |  | |||

| |||||

Merklín is mentioned in a song that Feldkurat Katz sings when inebriated in the horse-drawn cab.

Background

Merklín is a village between Domažlice and Plzeň. At the latest population count (2006) the village had 1,035 inhabitants.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Merklín had 1,789 inhabitants of whom 1,659 (92 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Přestice, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Přestice.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Merklín were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 35 (Pilsen) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 (Pilsen).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Jednu chvíli se zdálo, že drkotáním drožky o dlažbu přichází k rozumu. To se posadil rovně a začal zpívat nějaký úryvek z neznámé písně. Může být též, že to byla jeho fantasie:

Vzpomínám na zlaté časy, když mne houpal na klíně, bydleli jsme toho času u Domažlic v Merklíně.

Literature

| Nymburk |  | |||

| |||||

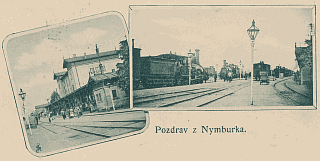

Nymburk station around 1900

Nymburk appears as Feldkurat Katz, during the cab drive back from Oberleutnant Helmich, talks drunken drivel about Nymburk station.

Background

Nymburk is a town with around 14,000 inhabitants by the Elbe. It is located 45 km east of Prague and is amongst other things known as the town where Bohumil Hrabal grew up. This well known author was strongly influenced by Jaroslav Hašek.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Nymburk had 10,169 inhabitants of whom 10,050 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Nymburk, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Poděbrady.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Nymburk were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 36 (Jungbunzlau) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 (Pilsen).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Potom počal považovat drožku za vlak, a nahýbaje se ven, křičel do ulice česky a německy: „Nymburk, přestupovat!“

Also written:Nimburgde

Literature

| Podmokly |  | |||

| |||||

Podmokly is mentioned by Feldkurat Katz when he wants to jump out of the cab because he thinks he is on a train. It occurs to him that he is on the way to Podmoklí instead of Budějovice.

Background

Podmokly almost certainly refers to Podmokly, the name of four places in Czechia. Here the place in question has a railway station, so it is by near certainty Podmokly by Děčín. It was the last station before the German border and is indeed in the opposite direction of Budějovice. The German translation by Grete Reiner underpins this assumption by using the name Bodenbach.

The town was until 1945 largely populated by German-speakers. Podmokly is now part of Děčín and the station has been renamed Děčín hlavní nádraží. It is the last stop before the German border and all trains from Prague to Berlin stop here.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Podmokly had 13,412 inhabitants of whom 608 (4 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Děčín, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Děčín.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Podmokly were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 42 (Leitmeritz) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 9 (Leitmeritz).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Jen jednou učinil pokus se vzbouřit a vyskočit z drožky, prohlásiv, že dál již nepojede, že ví, že místo do Budějovic jedou do Podmoklí.

Also written:Bodenbachde

| Gorgonzola |  | |||

| |||||

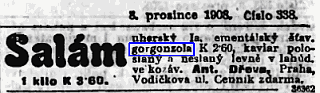

,8.12.1908

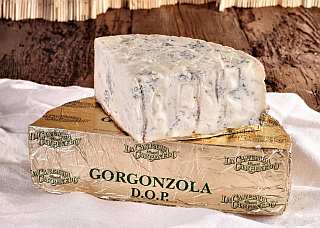

Gorgonzola is mentioned by Feldkurat Katz in the cab on the way home from Oberleutnant Helmich. The drunk Katz asks Švejk various questions: if he is married, if he enjoys eating gorgonzola cheese, and even if his home has ever been infested with bed bugs!

Background

Gorgonzola her refers to the famous blue cheese from Gorgonzola by Milan. The cheese has a history that goes back more than one thousand years and was obviously very well known also in Austria-Hungary. It was amongst other places produced at the dairy in Hall in Tirol (who also produced Emmental and many other well known cheeses).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Byl také zvědav, není-li prosinec nebo červen, a projevil velkou schopnost klásti nejrůznější otázky: „Jste ženat? Jíte rád gorgonzolu? Měli jste doma štěnice? Máte se dobře? Měl váš pes psinku?“

Literature

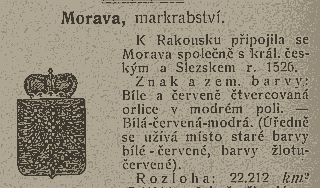

| Moravia |  | |||

| |||||

Moravia is first mentioned by Feldkurat Katz when he tells Švejk that he here had drunk the best borovička (juniper spirits) ever. The region enters the discussion a few more times, for instance in Putim in [II.2], in connection with the conscientous objector Nemrava, and in a conversation with Feldkurat Martinec in [IV.2].

Several locations in Moravia are mentioned in the The Good Soldier Švejk; amongst them Brno, Moravská Ostrava, Frýdlant nad Ostravicí, Místek, Jihlava, Hodonín, Přerov, Hostýn, Šternberk and Nový Jičín.

Several people from Moravia are also mentioned: Archbishop Kohn, Feldkurat Martinec, Feldoberkurat Lacina, Jos. M. Kadlčák, Nemrava, and last but not least: Professor Masaryk.

Background

Moravia is a historic region in Central Europe which is no longer an administrative unit. Together with Bohemia and a small part of Silesia it makes up Czechia. The capital is Brno and the region is named after the river Morava (de. March).

Other important cities were Moravská Ostrava (industry) and Olomouc that was (and is) an arch-bishop's seat and a prominent centre of education. Olomouc was also the reserve capital of the Habsburgs in periods when Vienna was under threat. During the times of Austria-Hungary Moravia had status as Kronland. In 1910 Czechs made up over 70 per cent of the population, but Germans formed a substantial minority. In cities like Brno, Olomouc, Vyškov and Jihlava they were in majority.

Jaroslav Hašek travelled here far less frequently here than in Bohemia but passed by on trips to Galicia and Slovakia every year from 1900 to 1903, and in 1905 he visited Jihlava. In early August 1903 his stay was involuntarily extended; he was arrested for vagrancy in Frýdek-Místek.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the duchy is briefly mentioned at the start of chapter 5. The author notes that the Russian army had occupied Lvov and encircled Przemyśl. In Serbia the Austrian army was in trouble, in Prague people were happy and in Mähren they were making preparations to bake cakes to welcome the cossacks. This had happened when Švejk was in prison at the start of the war.[1]

Mezitím co byl Švejk zavřen, ruská vojska zabrala Lvov, oblehla Přemyšl, dole v Srbsku stálo to také velmi špatně s rakouskou armádou, lidé v Praze byli veselí a na Moravě dělali již přípravy k pečení koláčů, až přijdou kozáci.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.3] Taková borovička není ani chutná, nemá ani barvu, pálí v krku. A kdyby byla aspoň pravá, destilát z jalovce, jakou jsem jednou pil na Moravě. Ale tahle borovička byla z nějakého dřevěného lihu a olejů.

[I.14.3] Nejvíc mně dalo práce ho přebarvit, aby měl barvu pepř a sůl. Tak se dostal se svým pánem až na Moravu a vod tý doby jsem ho neviděl.

[I.15] Nikdy nedorazil nikam včas, vodil pluk v kolonách proti strojním puškám a kdysi před lety stalo se při císařských manévrech na českém jihu, že se úplně s plukem ztratil, dostal se s ním až na Moravu, kde se s ním potloukal ještě několik dní po tom, když už bylo po manévrech a vojáci leželi v kasárnách.

[II.2] Všichni měli naději, že válka musí za měsíc, dva skončit. Měli představu, že Rusové už jsou za Budapeští a na Moravě. Všeobecně se to v Putimi povídá.

[II.2] Tato nová situace umožnila ruským vyzvědačům, při pohyblivosti fronty, vniknutí hlouběji do území našeho mocnářství, zejména do Slezska i Moravy, odkud dle důvěrných zpráv velké množství ruských vyzvědačů odebralo se do Čech.

[II.3] Než to jsou věci vedlejší, ač by zajisté nebylo na škodu, kdyby se váš redaktor Světa zvířat dříve přesvědčil, komu vytýká hovadinu, nežli nájezd vyjde z pera, třeba je určen na Moravu do Frýdlandu u Místku, kde byl do tohoto článku též odbírán váš časopis.

[II.3] Před vojnou žil na Moravě nějakej pan Nemrava, a ten dokonce nechtěl vzíti ani flintu na rameno, když byl odvedenej, že prej je to proti jeho zásadě, nosit nějaký flinty. Byl za to zavřenej, až byl černej, a zas ho nanovo vedli k přísaze. A von, že přísahat nebude, že je to proti jeho zásadě, a vydržel to.“

Also written:MoravaczMährende

Literature

- Mähren,

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

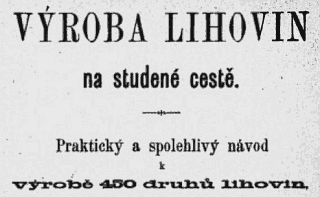

| Josefov |  | ||||

| ||||||

Výroba lihovin na studené cestě, 1877

Břetislav Hůla. Vysvětlíky.

© LA-PNP

Josefov is first mentioned through the term "of the Jews" when Feldkurat Katz tells Švejk how spirits ought to be manufactured, and not cold distilled in a factory by the Jews.

The district is mentioned again using the same term when Švejk is introduced to Oberleutnant Lukáš. The latter gives his "pucflék" a lecture in proper behaviour, which does not include stealing his masters parade uniform and sell it "in the Jews" (i.e. Josefov), like one of his previous servants did.

Later on, in [IV.2], the same expression is used in an anecdote Švejk tells feldkurát Feldkurat Martinec in the cell in Przemyśl (see porter Faustýn). The word Josefov is never explicitly used in the novel.

Background

Josefov is part of Prague, Staré město. Until 1922 it was a separate urban district also known as Praha V. From the late 19th century onwards it went through a redevelopment that changed the character of the quarter drastically, and few of the old buildings survived.

Prague V. was the smallest of the districts in the city with only 76 houses. It also had the highest proportion of German-speakers of any district in the city. This was no doubt due to the high number of Jewish inhabitants. Josefov roughly consisted of the area west of Mikulášská třída towards Vltava.

The Jewish community in Prague was next to extinguished by the Nazis during the occupation from 1939 to 1945. The most famous resident of the area was arguably Franz Kafka. Egon Erwin Kisch was also born here.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Josefov had 3,376 inhabitants of whom 2,633 (77 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.3] Kořalka je jed,“ rozhodl se, „musí být původní originál, pravá, a nikoliv vyráběná ve fabrice na studené cestě od židů. To je jako s rumem. Dobrý rum je vzácností.

[I.14.3] "U mě musíte si čistit boty, mít svou uniformu v pořádku, knoflíky správné přišité a musíte dělat dojem vojáka, a ne nějakého civilního otrapy. Jest to zvláštní, že vy neumíte se žádný držet vojensky. Jen jeden měl ze všech těch mých sluhů bojovné vzezření, a nakonec mně ukradl parádní uniformu a prodal ji v Židech.

[IV.2] Já dál na světě bejt živ nemůžu, já poctivej člověk sem žalovanej pro kuplířství jako ňákej pasák ze Židů.

Also written:JosefovPczJüdisches VierteldeJødekvarteretno

Literature

| Vršovice |  | ||||

| ||||||

Vršovice 1910

Vršovice is mentioned 15 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Vršovice was where Švejk dropped by to borrow money from Oberleutnant Mahler. There is another and longer visit in the next chapter when the field chaplain and his servant go there to recuperate the field altar. See Vršovice kostel. In [I.14] and [I.15], the plot for the most part takes place in Vršovice, without this being stated explicitly. This was when Švejk was a servant for Oberleutnant Lukáš.

Background

Vršovice is from 1922 a district in Prague, now contained entirely within the capital's 10th district but at Švejk's time it was still a separate town.

Hašek in Vršovice

Jaroslav Hašek lived in Vršovice with his wife Jarmila in 1911 and 1912, and it was here in house no. 363 (Palackého třída, now Moskevská) that his son Richard was born on 2 May 1912. The author was registered at this address on 28 December 1911, but already on 29 July 1912 he was listed in Vinohrady. His wife had also moved, to her parents in Dejvice. The split must obviously have happened very soon after their son was born.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí Vršovice is mentioned only in passing when a fellow at k.u.k. Militärgericht Prag whistles the song Když jsem já šel do Vršovic na posvícení.[1]

Tam chodily služky a paničky z nákupu, nějaký hoch si hvízdal pronikavě "Když jsem já šel do Vršovic na posvícení".

Demography

According to the 1910 census Vršovice had 24,646 inhabitants of whom 23,132 (93 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Vršovice, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Královské Vinohrady.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Vršovice were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag). In 1910 Vršovice hosted more than one thousand military employees and there were two barracks in town. At the outbreak of war IR73 ("Egerregiment") was garrisoned here with staff and three battalions. They remained here until the end of the war. See Vršovice kasárna.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.4] "Seděl jsem zde 5. června 1913 a bylo se mnou slušně zacházeno. Josef Mareček, obchodník z Vršovic: A byl tu i nadpis otřásající svou hloubkou: "Milost, velký bože . . ." a pod tím: "Polibte mně p."

[I.6] "A což policejního psa byste si nepřál?" otázal se Švejk, "takovýho, kerej hned všechno vyslídí a přivede na stopu zločinu. Má ho jeden řezník ve Vršovicích a on mu tahá vozejk, ten pes se, jak se říká, minul se svým povoláním."

[I.8] "To nic není," řekl druhý, "ve Vršovicích je jedna porodní bába, která vám za dvacet korun vymkne nohu tak pěkně, že jste mrzák nadosmrti".

[I.10.3] Jestli tam nepochodíte, tak půjdete do Vršovic, do kasáren k nadporučíkovi Mahlerovi.

[I.11.2] On sedí kvůli nějaké ukradené almaře a naše pohovka je u jednoho učitele ve Vršovicích.

[I.11.2] Od rozespalé ženy obchodníka se starým nábytkem dozvěděli se adresu učitele ve Vršovicích, nového majitele pohovky. Polní kurát projevil neobyčejnou štědrost. Štípl ji do tváře a zalechtal pod bradou.

Šli do Vršovic pěšky, když polní kurát prohlásil, že se musí projít na čerstvém vzduchu, aby dostal jiné myšlénky.

Ve Vršovicích v bytě pana učitele, starého nábožného pána, čekalo je nemilé překvapení. Naleznuv polní oltář v pohovce, starý pán domníval se, že je to nějaké řízení boží a daroval jej místnímu vršovickému kostelu do sakristie, vyhradiv si na druhé straně skládacího oltáře nápis: „Darováno ku cti a chvále boží p. Kolaříkem, učitelem v. v. Léta Páně 1914.“ Zastižen jsa ve spodním prádle, jevil velké rozpaky.

[I.11.2] A když tam viděl miniaturní skládací třídílný oltář s výklenkem pro tabernákulum, že klekl před pohovkou a dlouho se vroucně modlil a chválil boha a že to považoval za pokyn z nebe, ozdobit tím kostel ve Vršovicích.

[I.11.2] Domníval jsem se, že mohu takovým božím řízením posloužiti k ozdobení našeho chudého chrámu Páně ve Vršovicích."

[I.11.2] Přijal jsem polní oltář, který se náhodou dostal do chrámu ve Vršovicích.

[I.14.6] Zabočil jsem do Jindřišské, kde jsem mu dal novou porci. Pak jsem ho, když se nažral, uvázal na řetízek a táh jsem ho přes Václavské náměstí na Vinohrady, až do Vršovic.

[II.3] Byli tam známí z Vršovic a ty mně pomohli. Ztřískali jsme asi pět rodin i s dětma. Muselo to bejt slyšet až do Michle a potom to taky bylo v novinách o tej zahradní zábavě toho dobročinnýho spolku nějakejch rodáků ňákýho města.

Credit: Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

- Chronologie věčného stěhování,

- Úplný všeobecný adresář města Vršovic na rok 1910-1911,

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

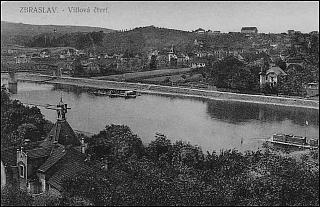

| Zbraslav |  | |||

| |||||

Zbraslav is mentioned in Feldkurat Katz's drunken drivel in the cab when he thinks Švejk is a lady who owns a villa in Zbraslav.

Background

Zbraslav is an area of Prague, 10 km south of the centre, where the river Berounka flows into Vltava. Zbraslav became part of Prague as late as 1974.

Zbraslav was in 1913 a community of 1,772 inhabitants in the okres of the same name, hejtmanství Smíchov. Zbraslav had both a parish and a post office. The district was however much larger with its 28,094 inhabitants. It contained several places that are mentioned in the novel: Záběhlice, Všenory, Mníšek and Chuchle.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Zbraslav had 1,772 inhabitants of whom 1,767 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Zbraslav, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Smíchov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Zbraslav were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.3] Vy máte vilu na Zbraslavi. A můžete jezdit parníkem po Vltavě. Víte, co je to Vltava?“

Also written:Königsaalde

Literature

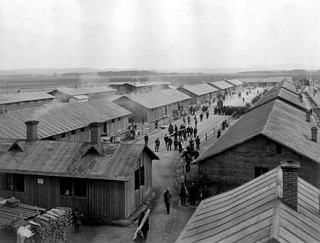

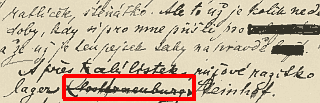

| Steinhof |  | |||||

| |||||||

Was Thalerhof the k.u.k Konzentrationslager Steinhof that Hašek had in mind?

,13.12.1914

Steinhof was the concentration camp where Mrs. Müllerová was interned without ever having been convicted. She had been taken away the same evening as she had pushed Švejk to the draft commission in a wheelchair.

Background

Steinhof is referred to by the author as a concentration camp, but it is unclear which place he has in mind. Steinhof by Vienna is an unlikely candidate although the name fits. From 1907 it was the location of the largest psychiatric institution in the Dual Monarchy, but there was no concentration camp here during World War I.

Shots in the dark

Milan Hodík thinks he may have had Stein an der Donau in mind, there was a prison there. Radko Pytlík suggests Kamenný Dvůr (former Steinhof) by Cheb but is unsure. Antonín Měšťan claims that there was a concentration camp in Steinhof, but he does not indicate where this "Steinhof" actually was[a].

Steinklamm

Jaroslav Šerák points to another possible mix-up with names. Here the possibility is Steinklamm, a camp in Bezirk St. Pölten that in 1914 was opened to cater for refugees but that later was used for prisoners, also for politically suspect civilians. As in Thalerhof cases of spotted typhus were recorded, and in early May 1915 these were reported in several newspapers.

Last minute name change

Klosterneuburg replaced with Steinhof in the manuscript (page 107)

© LA-PNP

The manuscript of Švejk is also worth a study. The author has actually started off by locating the camp in Klosterneuburg before he struck the word and changed it to Steinhof. It might therefore be prudent not to read too much into the choice of name for the camp where Müllerova's was interned.

The Dual Monarchy's concentration camps

None of the above suggestions fit the official overview of internment camps in Austria-Hungary. In 1916 there were three of them, located in Thalerhof by Graz, Nézsider (Neusiedl) and Arad (Oradea)[b].

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In the end the best indicator is Jaroslav Hašek himself and Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí. Here the camp Thalerhof is mentioned directly and the author even lets Švejk get interned here. For unknown reasons Hašek names the camp Thalerhof-Zelling.[1]

One hence assumes that the author had Thalerhof in mind when he penned this sequence of The Good Soldier Švejk. It was one of the first concentration camps in Europe, operating from 5 September 1914. Most of the inmates were politically suspect Ruthenian "russophiles" (i.e. Ukrainians) but a number of Czechs also found their way there.

Mezitím co byl Švejk zavřen, ruská vojska zabrala Lvov, oblehla Přemyšl, dole v Srbsku stálo to také velmi špatně s rakouskou armádou, lidé v Praze byli veselí a na Moravě dělali již přípravy k pečení koláčů, až přijdou kozáci.

Antonín Měšťan

So gab es in Steinhof in der Tat während des Ersten Weltkriegs ein österreichisches Konzentrationslager (I. 113/118) sowie in Hainburg eine Kadettenschule (I. 268/274).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.4] Starou paní soudili vojenskými soudy a odvezli, poněvadž jí nic nemohli dokázat, do koncentračního tábora do Steinhofu.

[I.10.4] A přes celý lístek růžové razítko: Zensuriert. K.u.k. Konzentrationslager Steinhof.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák, AME, Radko Pytlík

Literature

- Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, ,1921

- Flucht und Vertreibung,

- The Internment of Russophiles in Austria-Hungary, Serhiy Choliy,17.11.2020

- Beiblatt zum Verordnungsblatte für das k. und k. Heer, ,18.3.1916 [b]

- Die Flecktyphusfälle, ,2.5.1915

- Terrorism in Bohemia, ,16.12.1917

- Zápisky z vyhanství, ,4.12.1919

- Realien und Pseudorealien in Hašeks "Švejk", ,1983 [a]

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| a | Realien und Pseudorealien in Hašeks "Švejk" | 1983 | |

| b | Beiblatt zum Verordnungsblatte für das k. und k. Heer | 18.3.1916 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

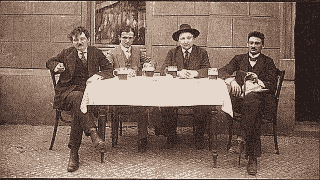

| Smíchov |  | |||

| |||||

Kol. 1900 • Pohled do Nádražní ulice na Smíchově s pivovarem (dům čp. 43 na Smíchově)

Smíchov is mentioned 4 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Smíchov is briefly mentioned when a locksmith from the district approaches Švejk outside U kalicha when he was back there for the last time.In the famous farewell scene between Švejk and Sappeur Vodička in Királyhida [II.4] the Smíchov beer is mentioned. Otherwise Smíchov rarely figures in the novel, but in [III.4] it is revealed that Leutnant Dub lived here.

Background

Smíchov is a district of Prague, located west of the Vltava, in the southern part of the city. Smíchov has a major railway station, is an industrial area, and is the home of the Staropramen brewery. Smíchov became part of Prague in 1922.

In 1914 Smíchov was a town which that with its surrounding district contained large part of what is now the western part of Prague. It was centre of hejtmanství and okres of the same name, and the district Smíchov was very populous with 167,830 inhabitants (1910) - in effect larger than any district in Bohemia apart from Prague. Okres Smíchov alone counted 139,736 inhabitants of which around 95 per cent were Czechs. The hejtmanství also contained okres Zbraslav. Within okres Smíchov itself, several places we know from The Good Soldier Švejk were located. Amongst those are Břevnov, Dejvice, Klamovka, Kobylisy, Košíře, Motol, Roztoky and Horní Stodůlky.

Hašek and Smíchov

Pod černým vrchem in 1912

Jaroslav Hašek lived in Smíchov from 1909 to 1911, or more precisely in Košíře where he was editor of the magazine Svět zvířat and later ran his Cynological Institute (see Psinec nad Klamovkou). There are many places in Smíchov associated with the author, not least the pub Pod černým vrchem where Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona held some of their meetings and where the famous picture of four party members with the four beers was taken[a].

Demography

According to the 1910 census Smíchov had 51,791 inhabitants of whom 47,348 (91 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Smíchov, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Smíchov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Smíchov were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.4] Při té rozmluvě byl jeden starší pán, zámečník ze Smíchova, který šel ke Švejkovi a řekl k němu: „Prosím vás, pane, počkejte na mne venku, já s vámi musím mluvit.“

[II.4] Potom se vzdálili a bylo slyšet zas za hodnou chvíli za rohem z druhé řady baráků hlas Vodičky: „Švejku, Švejku, jaký mají pivo ,U kalicha’?“ A jako ozvěna ozvala se Švejkova odpověď: „Velkopopovický.“ „Já myslel, že smíchovský,“ volal z dálky sapér Vodička. „Mají tam taky holky,“ křičel Švejk. „Tedy po válce v šest hodin večer,“ křičel zezdola Vodička.

[II.5] Tak si dal natisknout někde na Smíchově obrázky sv. Pelegrinusa a dal je posvětit v Emauzích za 200 zl.

Literature

- Jaroslav Hašek,

- HAŠEK Jaroslav - Na domě čp.908 …,

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021 [a]

- Pivovar Staropramen Praha, ,1.1.2000

| a | Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky | 2009 - 2021 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

10. Švejk as a military servant to the field chaplain | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |