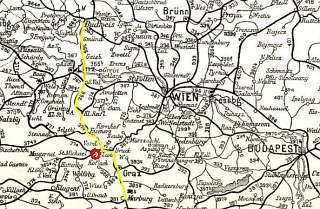

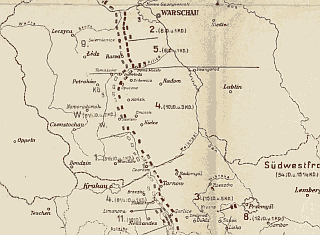

Švejk's journey on a of Austria-Hungary from 1914, showing the military districts of k.u.k. Heer. The entire plot of The Good Soldier Švejk is set on the territory of the former Dual Monarchy.

The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (mostly known as The Good Soldier Švejk) by Jaroslav Hašek is a novel that contains a wealth of geographical references - either directly through the plot, in dialogues or in the author's narrative. Hašek was himself unusually well travelled and had a photographic memory of geographical (and other) details. It is evident that he put a lot of emphasis on geography: Eight of the 27 chapter headlines in the novel contain geographical names.

This web site will in due course contain a full overview of all the geographical references in the novel; from Prague in the introduction to Klimontów in the unfinished Part Four. Continents, states (also defunct), cities, market squares, city gates, regions, districts, towns, villages, mountains, mountain passes, oceans, lakes, rivers, caves, channels, islands, streets, parks and bridges are included.

The list is sorted according to the order in which the names appear in the novel. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's translation from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by these examples: Sanok a location where the plot takes place, Dubno mentioned in the narrative, Zagreb part of a dialogue, and Pakoměřice mentioned in an anecdote.

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60) II. At the front

II. At the front  2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (38)

1. Across Magyaria (38) 2. In Budapest (38)

2. In Budapest (38) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50) 4. Forward March! (42)

4. Forward March! (42)

|

II. At the front |

| |

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train | |||

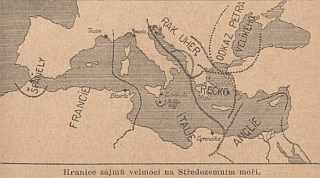

| Mediterranean Sea |  | |||

| |||||

"Grégrova příručka", , 1912

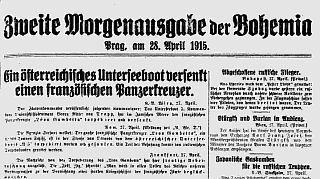

, 28.4.1915

, 17.5.1915

Mediterranean Sea is just about mentioned as Oberleutnant Lukáš on the train to Budějovice reads in Bohemia about the success of the German submarine "E" and bombs thrown from aeroplanes that explode three times in a row.

Background

Mediterranean Sea is an ocean between Europe and Africa, with western Asia to the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The following countries bordering the Mediterranean participated in World War I: Austria-Hungary, France, Italy, Greece, Montenegro og Turkey.

Austria-Hungary had access to Mediterranean Sea from Trieste and along the coast of Dalmatia down to Montenegro, k.u.k. Kriegsmarine possessed a sizeable fleet. Their main base was at Pola (now Pula, Croatia). During the war they were however limited to operations in the Adriatic See as the Entente blockaded the sea at the southern tip of Italy.

Submarines in the Mediterranean

At the time the episode is supposed to have taken place (late 1914 or early 1915) there were no German U-boats in the Mediterranean Sea, they only appeared later that year. Not could they have been called "E" as all German U-boats had names starting with "U" (Unterseeboot). The German air force did however use war planes classed "E" (Eindecker), so perhaps the author swapped U-boats with aeroplanes?

Austro-Hungarian U-boats were also designated by the letter "U". They had been active in the Adriatic See from the outbreak of war, and on 27 April 1915 the French cruiser Léon Gambetta was torpedoed by "U-5". In 1914 k.u.k. Kriegsmarine owned 5 U-boats, a number that rose to 26 by 1918. Almost all of them were built in Germany.

Hans-Peter Laqueur

In the train from Prague to Budweis (late December 1914) Lukasch reads in the „Bohemia“ about the successful actions of the German submarine „E“ in the Mediterranean Sea:

* There was no German submarine „E“. „E“ and a number was used by submarines of the Royal Navy.

* There were no German submarines in the Mediterranean before May 1915 (cf. Hans Werner Neulen, Adler und Halbmond. Das deutsch-türkische Bündnis 1914-1918. Frankfurt/Berlin 1994, p. 91 ff.).

Hašek probably refers to the actions of U 35 sinking 12 ships with a total 48813 GRT in October/November 1915 (cf. de.wikipedia: „Waldemar Kophamel“ and „SM U 35“) or of U 38 (14 ships, 47460 GRT), late 1915 as well (cf. de.wikipedia: „Max Valentiner“ and „SM U 38“).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Nadporučíkovi bezděčně zacvakaly zuby, vzdychl si, vytáhl z pláště „Bohemii“ a četl zprávy o velkých vítězstvích, o činnosti německé ponorky „E“ na Středozemním moři, ...

Credit: Hans-Peter Laqueur

Also written:Středozemní mořeczMittelmeerdeMar MediterraneoitMare Mediterraneumla

Literature

- Deutsche Unterseeboote ins Mittelmeer?, ,4.5.1915

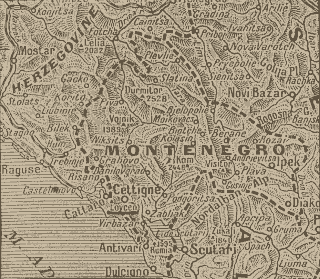

| Montenegro |  | |||

| |||||

, 17.1.1916

, Volume 7

Southern Dalmatia towards Montenegro

, 1914

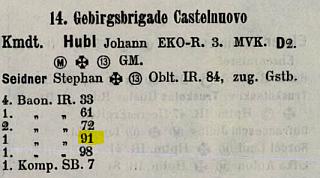

IR. 91, 1st Baon. by Cattaro.

, 1914

Montenegro is mentioned in the description of Generalmajor von Schwarzburg who punished breaches of service regulations by transferring the culprit to some drink-infested and dirty garrison in a desolate corner of Galicia or to the border with Montenegro.

Background

Montenegro (Црна Гора) was in 1914 an independent kingdom and had been a duchy (kingdom from 1910) since the liberation from Turkey in 1878. King at the time was Nikola I. and the capital was Cetinje.

Today Montenegro is again an independent state, after having been part of various south slav federations from 1918 until 2006 (except 1941-45). The language is Serbian, is written with the Cyrillic script and the religion is mainly orthodox.

In 1914 the kingdom of Dalmatia (as part of Austria) and Bosnia-Hercegovina both shared a short border with Montenegro and both k.u.k. Heer and k.u.k. Kriegsmarine had garrisons in the region. The navy had a heavy presence in Cattaro (Kotor), and it was one of empire's three naval bases. The border between Herzegovina and Montenegro was much longer and this region also had a significant military presence. In this context we will however need to look for army garrisons in southern Dalmatia.

Montenegro at war

In World War I the kingdom quickly aligned with Serbia and declared war on Austria-Hungary on 7 August 1914. Along the border there was fighting already from August 1914 but it remained a stalemate until k.u.k. Wehrmacht launched a full-scale invasion of Montenegro on 5 January 1916. The invasion was made possible by the recent defeat of Serbia, making large forces available for the attack, and it was now also possible to attack from Serbian territory. King Nikola I. sued for peace, but the terms were so harsh that he rejected them. Because he had fled the country, the king could not stop the politicians that remained from accepting the terms. On 19 January the treaty was signed and Montenegro remained occupied for the rest of the war.

The Austrian-Montenegrin border

Hašek mentions the regions bordering Montenegro, so let us try to identify the garrisons to where officers may have been sent by the fearsome army inspector, Generalmajor von Schwarzburg.

Dalmatia and k.u.k. Heer

Korpskommando Nr. 16 was located at Ragusa (Dubrovnik) which was the main garrison town in the border regions. Further there were army units stationed at Castelnuovo (Herceg-Novi), Trebinje, and Bileća. The latter two were in Hercegovina.

Of particular interest is Castelnuovo as it hosted the 47. Infanteriedivision. Assigned to this unit was also the 1st battalion of IR. 91 who had been garrisoned here since 1906 as part of 14. Gebirgsbrigade (14th Mountain Brigade). In 1907 and 1908 they were located in Budua (Budva), in 1909 and 1910 in Cattaro, in 1911 in Crkvice, in 1912 Perzagno (Prčanj), in 1913 and 1914 Teodo (Tivat)[1]. Individual units were at the outbreak of war scattered: Teodo, Kozmač, Sutomore, Castellastua (Petrovac). Staničičkaserne in Teodo was the main site of the battallion.

1. Years are according to from Schematismus and thus usually reflects the state of the previous year. When a unit is listed from 1907 it therefore means that they were moved here already in 1906.

Budva was actually the southernmost garrison in the entire empire. The former commander of IR. 91, 1. battalion, Franz Graf, later wrote that being sent there was like being exiled, having to "spend years away from women, beer and the domestic conviviality". Still, all who had been there agreed it was a beautiful place. The biggest problem was however the distance to home, and in the spring the soldiers from South Bohemia longed after some good beer. They could get hold of strong Dalmatian wine but it was often poisonous!

The battalion remained in the area also during the first month of the war but from 5 September 1914 they were transported by train to the front against Serbia further north. They joined the rest of the regiment as late as 1916, on the Italian front. At least one familiar name from The Good Soldier Švejk served in southern Dalmatia before the war: Josef Adamička. It is also possible that Jan Vaněk served here during the first month of the war. A more marginal figure from the novel, Oberleutnant Wurm, served here as commander of the battalion's machine gun unit.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Měl manii přeložit vždy důstojníka na nejnepříjemnější místa. Stačilo to nejmenší, a důstojník se již loučil se svou posádkou a putoval na černohorské hranice nebo do nějakého opilého, zoufalého garnisonu v špinavém koutě Haliče.

[II.5] „Já z toho nemám moc velkou radost,“ důvěrně se ozval účetní šikovatel, „vypravoval stábsfeldvébl Hegner, že pan hejtman Ságner v Srbsku na počátku války chtěl někde u Černé Hory v horách se vyznamenat a hnal jednu kumpačku svého baťáčku za druhou na mašíngevéry do srbských štelungů, ačkoliv to byla úplně zbytečná věc a infanterie tam byla starýho kozla co platná, poněvadž Srby odtamtud s těch skal mohla dostat jen artilerie.

Also written:Černá HoraczЦрна Гораsb

Literature

- Dislokationswechsel beim 1./91. Feldbataillon in Süd-Dalmatien, ,3.10.1913

- Die südlichsten Garnisonen der alten Monarchie, Franz Graf,1924-1928

- Mit dem I./91. Feldbataillon gegen Montenegro, W. Tobner,1924-1928

- Kolem boky Kotorské, Fratišek Češka,10.9.1936

- Montenegro erklærer Østerrike krig, ,8.8.1914

- Montenegro klemmes, ,13.1.1916

- La capitale del Montenegro è caduta?, ,15.1.1916

| Styria |  | |||

| |||||

Styria is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about tailor Hývl who had a slip of tongue on the train route Maribor - Leoben - Prague because he thought no-one else in the compartment spoke Czech.

Background

Styria was until 1918 one of 15 crown lands of Cisleithania. The area was larger than the current Austrian state of Styria as it included parts of current Slovenia with Maribor (Marburg). The capital was (and is) Graz, and at the time a significant part of the population were Slovenes (nearly 30 per cent).

Hašek and Styria

The author's inspiration for the use of Styria (and the described train route) as a theme in the novel is probably a trip he undertook in the summer of 1905. His travel companions for parts of this apostolical journey were painter Jaroslav Kubín and the actor František Vágner. His travels that year is described by Václav Menger and is also featured in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Hašek also touches on the journey in the stories Rozjímání o počátku cesty and O sportu.

Jaroslav Hašek: O sportu (1907)

Bylo to předloni, když z nedostatku peněz šel jsem pěšky z Terstu přes Alpy do Prahy. Vandroval jsem, což předpokládá, že jsem fechtoval. V Lubně ve Štýru zastavil jsem na silnici tři muže, kteří vyhlíželi jako turisti, a prostým způsobem: Ein armer Reisender žádal jsem je o podporu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] To nám jednou před léty vypravoval krejčí Hývl, jak jel z místa, kde krejčoval ve Štyrsku, do Prahy přes Leoben a měl s sebou šunku, kterou si koupil v Mariboru.

Also written:ŠtýrskoczSteiermarkdesl

Literature

- O sportu, Jaroslav Hašek,27.1.1907

- Rozjímání o počátku cesty, Jaroslav Hašek,9.1926

- Herzogtum Steiermark,

| Leoben |  | |||

| |||||

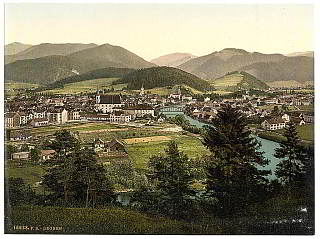

Leoben around 1900

,1900

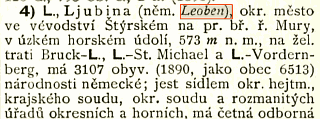

Leoben is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about tailor Hývl who had a slip of tongue on the train route Maribor - Leoben - Prague because he thought no one else in the compartment understood Czech.

Background

Leoben is the second-largest city in the Austrian state of Styria with around 25,000 inhabitants. It is situated on the river Mur, 541 metres above sea level, 46 kilometres north-west of Graz.

In 1914 it was also within Styria, it was a district capital and also housed the district court. The town had a mining academy and was primarily a mining community. The population was almost exclusively German.

Interestingly Švejk used the German name of the town, although the Czech variants Lubno and also Ljubina were often used, even officially in for instance Ottův slovník naučný.

In the story O sportu, printed on 27 January 1907, Hašek mentions Leoben, but here he used the Czech term Lubno. He notes that he visited two years ago, was penniless, and had to beg money to get back home.

Hašek and Styria

The author's inspiration for the use of Styria (and the described train route) as a theme in the novel is probably a trip he undertook in the summer of 1905. His travel companions for parts of this apostolical journey were painter Jaroslav Kubín and the actor František Vágner. His travels that year is described by Václav Menger and is also featured in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Hašek also touches on the journey in the stories Rozjímání o počátku cesty and O sportu.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Leoben had 11 459 inhabitants. The judicial district was Gerichtsbezirk Leoben, administratively it reported to Bezirkshauptmannschaft Leoben.

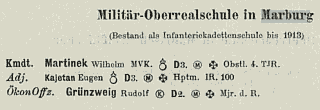

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Leoben were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 27 (Graz) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 3 (Graz). K.u.k. Heer had no presence in the town but it housed a battalion from k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 3. It was also the seat of the Landsturmexpositur of the military district.

Jaroslav Hašek: O sportu (1907)

Bylo to předloni, když z nedostatku peněz šel jsem pěšky z Terstu přes Alpy do Prahy. Vandroval jsem, což předpokládá, že jsem fechtoval. V Lubně ve Štýru zastavil jsem na silnici tři muže, kteří vyhlíželi jako turisti, a prostým způsobem: Ein armer Reisender žádal jsem je o podporu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] To nám jednou před léty vypravoval krejčí Hývl, jak jel z místa, kde krejčoval ve Štyrsku, do Prahy přes Leoben a měl s sebou šunku, kterou si koupil v Mariboru.

Literature

- O sportu, Jaroslav Hašek,27.1.1907

- Rozjímání o počátku cesty, Jaroslav Hašek,9.1926

- Lubno, ,1900

| Maribor |  | |||

| |||||

Maribor is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about tailor Hývl who had a slip of tongue on the train route Maribor - Leoben - Prague because he thought no one else in the compartment spoke Czech. The tailor had bought a joint of ham here.

Background

Maribor is the second-largest city in Slovenia, located on the river Drava. The population number is now (2019) appx. 112,000.

Until 1918 it belonged to the Austrian crown-land of Styria and was at the time 80 per cent German-speaking. In 1890 it housed a bishop seat, and was the home several educational institutions as well as some industry.

One of the prototypes of characters from The Good Soldier Švejk, Rudolf Lukas, attended a preparatory course for cadet school here from 1903 until 1904. Another well-known prototype, Ludvík Lacina, also spent some time here, as Feldkurat in 1912.

Hašek and Styria

The author's inspiration for the use of Styria (and the described train route) as a theme in the novel is probably a trip he undertook in the summer of 1905. His travel companions for parts of this apostolical journey were painter Jaroslav Kubín and the actor František Vágner. His travels that year is described by Václav Menger and is also featured in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Hašek also touches on the journey in the stories Rozjímání o počátku cesty and O sportu.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Maribor had 27 994 inhabitants.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Maribor were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 47 (Marburg) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 26 (Marburg). The garrison also contained an infantry cadet school, a cavalry brigade, and a garrison court.

Jaroslav Hašek: O sportu (1907)

Bylo to předloni, když z nedostatku peněz šel jsem pěšky z Terstu přes Alpy do Prahy. Vandroval jsem, což předpokládá, že jsem fechtoval. V Lubně ve Štýru zastavil jsem na silnici tři muže, kteří vyhlíželi jako turisti, a prostým způsobem: Ein armer Reisender žádal jsem je o podporu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] To nám jednou před léty vypravoval krejčí Hývl, jak jel z místa, kde krejčoval ve Štyrsku, do Prahy přes Leoben a měl s sebou šunku, kterou si koupil v Mariboru.

Also written:Marburgde

Literature

- O sportu, Jaroslav Hašek,27.1.1907

- Rozjímání o počátku cesty, Jaroslav Hašek,9.1926

- Maribor,

| Sankt Moritz |  | |||

| |||||

K.u.k Eisenbahnkarte 1905.

Sankt Moritz is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about tailor Hývl who had a slip of tongue on the train Maribor - Leoben - Prague because he thought that the other passengers didn't understand what he said. This unfortunate episode happened by Sankt Moritz.

Background

Sankt Moritz appears to have been somewhere in Austria between Leoben and Prague but no such place has been identified. Thus the author surely didn’t have the famous Swiss resort of the same name so the most likely candidate is Sankt Michael in Obersteiermark. This is a town on one of the possible routes between Maribor and Prague, soon after Leoben.

Hašek and Styria

The author's inspiration for the use of Styria (and the described train route) as a theme in the novel is probably a trip he undertook in the summer of 1905. His travel companions for parts of this apostolical journey were painter Jaroslav Kubín and the actor František Vágner. His travels that year is described by Václav Menger and is also featured in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Hašek also touches on the journey in the stories Rozjímání o počátku cesty and O sportu.

Jaroslav Hašek: O sportu (1907)

Bylo to předloni, když z nedostatku peněz šel jsem pěšky z Terstu přes Alpy do Prahy. Vandroval jsem, což předpokládá, že jsem fechtoval. V Lubně ve Štýru zastavil jsem na silnici tři muže, kteří vyhlíželi jako turisti, a prostým způsobem: Ein armer Reisender žádal jsem je o podporu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Jak tak jede ve vlaku, myslel si, že je vůbec jedinej Čech mezi pasažírama, a když si u Svatýho Mořice začal ukrajovat z tý celý šunky, tak ten pán, co seděl naproti, počal dělat na tu šunku zamilovaný voči a sliny mu začaly téct z huby. Když to viděl krejčí Hývl, povídal si k sobě nahlas: ,To bys žral, ty chlape mizerná.’

Also written:Svatý Mořiccz

Literature

- O sportu, Jaroslav Hašek,27.1.1907

- Rozjímání o počátku cesty, Jaroslav Hašek,9.1926

- Geschichte,

| Tábor |  | ||||

| ||||||

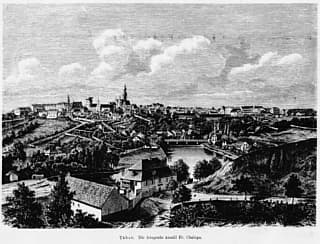

Tábor 1895

,16.7.1880

Tábor is mentioned 17 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Tábor plays an important role in the plot because the journey from Prague to Budějovice was unexpectedly halted before the town. This was after Švejk's many mishaps on the train, culminating in him pulling the emergency brake.

He didn't have enough money to pay the fine so at the station (see Táborské nádraží) he had to step off the train to explain himself. A helpful gentleman in the crowd paid the fine and gave him money but he was then hit by the misfortune that he drank one beer after the other while the train with Oberleutnant Lukáš continued to Budějovice where their regiment was garrisoned. Without documents and money he was in the end dispatched onwards on foot. This was the beginning of Švejk's famous anabasis where he without much luck tried to get to his regiment.

Background

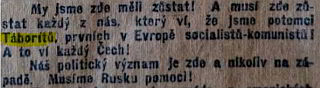

Tábor is a town in South Bohemia with about 35,000 inhabitants (2010). The historical centre is under protection and very attractive. The town was one of the hotbeds of the national/religious Hussite movement[1] and has therefore played an prominent role in Czech history. ,27.3.1918 © VHÚ

1. The Hussite movement was named after the religious reformer Hus (1369-1415), and was one of the first groups that broke with the Catholic church. For the Czech independence movement during World War I they were an important national symbol and continued as one of the mainstays in the nation building in Czechoslovakia in the inter-war years. The Taborites was a radical faction named after Tábor and had sufficient traits of socialism to raise the attention of Marxists. Jaroslav Hašek himself referred to them in the article K českému vojsku (To the Czech Army) that he had printed in the Communist newspaper Průkopník 27 March 1918.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Tábor had 11,926 inhabitants of whom 11,856 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Tábor, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Tábor. The town was therefore surely the ethnically "cleanest" major town in all of Bohemia. This complete "czechness" was also a result of not hosting permanent military units. Hence the usual contingent of German-speaking officers that were usually attached to a garrison was absent.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Tábor were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 (Neuhaus) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Pisek).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Zůstal průvodčí se Švejkem a mámil na něm dvacet korun pokuty, zdůrazňuje, že ho musí v opačném případě předvést v Tábořepřednostovi stanice. „Dobrá,“ řekl Švejk, „já rád mluvím se vzdělanejma lidma a mě to bude moc těšit, když uvidím toho táborskýho přednostu stanice.“

Literature

- Tábor, ,1864-1935

- Tábor,

- Úřední list, ,12.2.1915

- B(Tábor) průvodce po městě a jeho okolí, ,1886

- Průvodce okolím Tábora, ,1932

- Schematismus der k.k. Landwehr (s. 282), ,1914

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 527), ,1914

| Uhříněves |  | |||

| |||||

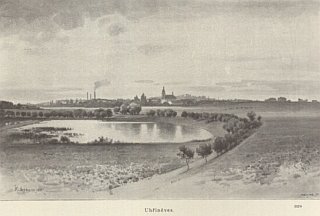

, 1903

Uhříněves is mentioned in the anecdote about Mlíčko František who like Švejk had pulled the emergency brake on a train. The incident is said to have happened in May 1912.

Background

Uhříněves is a suburb on the south-eastern outskirts of Prague, within current Prague 22. From 1913 until 1974 it was a separate town. It had (and has) a railway station but the express trains didn't stop here so Švejk and Oberleutnant Lukáš simply passed through it on their way to Budějovice in 1915.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Uhříněves had 2,677 inhabitants of whom 2,625 (98 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Říčany, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Žižkov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Uhříněves were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Poněvadž železniční zřízenec neodpovídal, prohlásil Švejk, že znal nějakého Mlíčka Františka z Uhříněvse u Prahy, který také jednou zatáhl za takovou poplašnou brzdu a tak se lekl, že ztratil na čtrnáct dní řeč a nabyl ji opět, když přišel k Vaňkovi zahradníkovi do Hostivaře na návštěvu a popral se tam a voni vo něho přerazili bejkovec. „To se stalo,“ dodal Švejk, „v roce 1912 v květnu.“

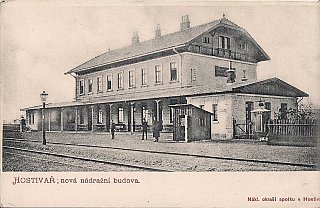

| Hostivař |  | |||

| |||||

Hostivař 1906

Hostivař is mentioned in the anecdote about Mlíčko František who also was unlucky and pulled the emergency brake of a train. The gardener gardener Vaněk came from here.

Later the place is mentioned in a story that Sappeur Vodička tells Švejk in Királyhida.

Background

Hostivař is an urban area on the south-eastern outskirts of Prague that since 1922 has been part of the capital. It has a railway station and is also the terminus of metro line A. Hostivař is also a popular area for recreation.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Hostivař had 2,495 inhabitants of whom 2,492 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Vršovice, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Královské Vinohrady.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Hostivař were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Poněvadž železniční zřízenec neodpovídal, prohlásil Švejk, že znal nějakého Mlíčka Františka z Uhříněvse u Prahy, který také jednou zatáhl za takovou poplašnou brzdu a tak se lekl, že ztratil na čtrnáct dní řeč a nabyl ji opět, když přišel k Vaňkovi zahradníkovi do Hostivaře na návštěvu a popral se tam a voni vo něho přerazili bejkovec. „To se stalo,“ dodal Švejk, „v roce 1912 v květnu.“

[II.3] „Plácnu taky ženskou, Švejku, mně je to jedno, to ještě neznáš starýho Vodičku. Jednou v Záběhlicích na ,Růžovým ostrově’ nechtěla se mnou jít jedna taková maškara tančit, že prej mám voteklou hubu. Měl jsem pravda hubu vopuchlou, poněvadž jsem právě přišel z jedný taneční zábavy v Hostivaři, ale považ si tu urážku vod tý běhny.

| Svitava |  | |||

| |||||

Zwittau, Oberer Stadtplatz

Svitava is mentioned in the anecdote about station master Wagner and switch operator Jungwirt.

Background

Svitava no doubt refers to Svitavy, a town in eastern Bohemia that in 1914 was predominantly German speaking. It is also known as the birthplace of Oskar Schindler, to whom the town has erected a monument. In 1866 the ceasefire between Austria and Prussia was signed here.

The river Svitava flows through the town and as Švejk says there it has a railway station. The German translation of Grete Reiner interprets it as Zittau (tsj. Žitava), a town in Germany bordering Bohemia.

Then in Moravia

In 1914 the town belonged to Moravia but it was situated only a few kilometres from the border with Bohemia.

Ambiguous terms

Although odd at first sight, Hašek's use of the term Svitava is not necessarily wrong. Svitava is the term used on Erben's map from 1883 and is listed in Ottův slovník naučný as an alternative for Svitavy.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Svitava had 9 649 inhabitants. The judicial district was okres Svitavy, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Moravská Třebová.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Svitava were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 93 (Mährisch Schönberg) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 13 (Olmütz).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Švejk vytáhl z bluzy dýmku, zapálil si, a vypouštěje ostrý dým vojenského tabáku, pokračoval: „Před léty byl ve Svitavě přednostou stanice pan Wagner. Ten byl ras na svý podřízený a tejral je, kde moh, a nejvíc si zalez na nějakýho vejhybkáře Jungwirta, až ten chudák se ze zoufalství šel utopit do řeky.

Also written:ZittauReinerSvitavyczZwittaude

| Stará brána |  | |||

| |||||

, 6.8.1914

Butchers in Tábor

Stará brána is mentioned by a man who is arrested for sedition at Táborské nádraží when Švejk steps off the train to pay his fine for having pulled the emergency brake. He defends himself by saying that he is a butcher from the Old Gate and that he didn't mean the utterance seriously.

Background

Stará brána (Old Gate) obviously refers to a town gate in Tábor but a gate with such a name didnt exist. It was therefore probably a colloquial name for Bechyňská brána, the only town gate that is still intact.

There were many butchers in Tábor in 1915 but it has not been possible to find out where they were located. The address directory only lists names, not the street addresses (Alois Chytil).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Nešťastný občan nezmohl se na nic jiného než na upřímné tvrzení, že je přece řeznický mistr od Staré brány a že to tak nemyslel.

Also written:Old GateenAlter TordeGamle Portno

Literature

| Zdolbunov |  | |||

| |||||

From Alexandr Drbal

,21.1.1911

K vítězné svobodě 1914-1918-1928

,1928

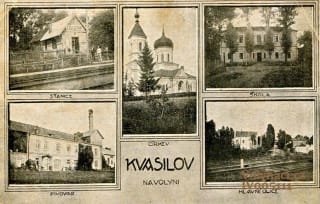

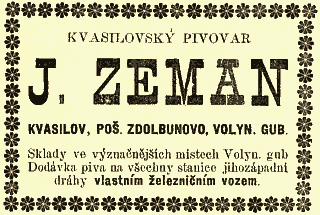

Zdolbunov is mentioned is a conversation between Švejk and a passenger at Tábor station. The stranger gives him the name of the brewer Zeman in Zdolbunov and urges him not too stay too long at the front. Švejk's answer more than suggests that he intends to let himself be captured, just as the author did.

Background

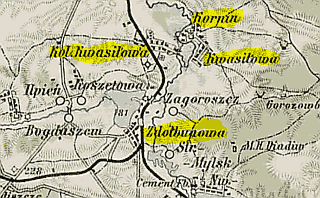

Zdolbunov (Здолбунов), now Zdolbuniv (Здолбу́нів) is a town and important railway junction in the Volhynia region of Ukraine, in 1915 still part of Russia. In the inter-war years it was Polish, and from 1939 until 1990 part of the Soviet Union[1].

Almost all period sources refer to the town as Zdolbunovo/Zdołbunów and so did probably Hašek. In the novel he used the locative case v Zdolbunově, so the nominative case may either have been Zdolbunov, Zdolbunovo, or Zdolbunova. The paper he wrote for in Kiev from 1916 to 1918, Čechoslovan, consistently used the term Zdolbunovo, so it is logical to assume that Hašek would have done the same. Older maps, both Russian and Austrian, even use Здолбуновa/Zdołbunowa.

The area had many Czech settlers who had emigrated from around 1860 onwards. The town also hosted sizeable Polish and Jewish populations. The brewery of the mentioned brewer Zeman was not located here but in Kvasilov (now Kvasyliv), 4 km to the north towards Rovno (now Rivne).

Hašek and Zdolbunovo

Hašek would probabily have passed through it shortly after being captured at Chorupan on 24 September 1915. Presumably the prisoners waited for onward rail transport here. The author surely also visited in 1916 and 1917 on his travels between Kiev and the front.

1. Bar the years 1941 to 1944 when it was occupied by Nazi Germany.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Když odcházel, řekl důvěrně k Švejkovi: „Tak vojáčku, jak vám povídám, jestli budete v Rusku v zajetí, tak pozdravujte ode mne sládka Zemana v Zdolbunově. Máte to přece napsané, jak se jmenuji. Jen buďte chytrý, abyste dlouho nebyl na frontě.“ „Vo to nemějte žádnej strach,“ řekl Švejk, „je to vždycky zajímavý, uvidět nějaký cizí krajiny zadarmo.“

Credit: Alexandr Drbal

Also written:ZdolbunovczZdołbunówplЗдолбуновruЗдолбунівua

Literature

- Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego..., ,1880 - 1914

- Kronika obce Kvasilova, ,1929

- Zdolbunovo v Rusku, ,20.10.1906

- J. Zeman, ,21.1.1911J

- Mezi Čechy na Volyni, ,21.9.1928

| Szeged |  | |||

| |||||

,14.5.1915

Avantgarde des Widerstands

,2000

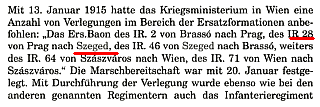

Szeged is mentioned in a conversation at Tábor railway station. A soldier from the Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 relates how Hungarians there mocked Czech soldiers by holding their hands up to demonstrate how easily the latter gave themselves up.

Background

Szeged is a city in southern Hungary, right on the Serbian border. It is the third largest city in Hungary and a major centre of education. It is located by the river Tisza.

Around 4 February 1915 the replacement battalion of Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 was transferred from Prague to Szeged, on of the first of many Czech regiments that were moved away from their recruitment districts. This was preventive move from k.u.k. Kriegsministerium against presumed disloyalty. Other regiments were moved later that year and it was the turn of Jaroslav Hašek and his Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 on 1 June, an event that is described in The Good Soldier Švejk.

The date of the transfer of Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 gives a certain clue as to the timing of events in the The Good Soldier Švejk - in general to be taken with a pinch of salt due to the novel's many anachronisms. Švejk must according to this logic have been in Tábor after 4 February 1915 because soldiers from IR28 hardly could have set foot in Szeged until then. The author himself passed Tábor in mid February 1915, so it is quite possible that he himself could have heard/experienced something similar at the time.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Szeged had 118 328 inhabitants. The judicial district was Szeged, administratively it reported to vármegye Csongrád.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Szeged were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 46 (Szeged) or Honvédinfanterieregiment Nr. 5 (Szeged).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Od vedlejšího stolu řekl nějaký voják, že když přijeli do Segedína s 28. regimentem, že na ně Maďaři ukazovali ruce do výšky.

Also written:SegedínczSzegedinde

Literature

- 28. pluk "Pražské děti", ,1932

- S osmadvacátníky za světové války, ,1936

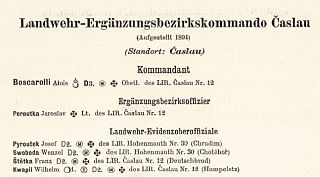

| Čáslav |  | |||

| |||||

Čáslav, 1906

, 1914)

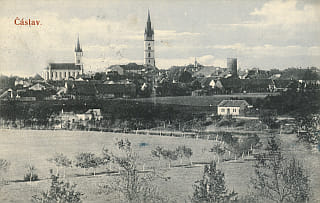

Čáslav is mentioned by a Landwehr-soldier at Táborské nádraží. The theme was the antagonism between Czechs and Germans. An editor from Vienna refused to speak Czech until he one day found himself in a march company with Czechs only. Then he suddenly understood their language.

Background

Čáslav is a town in central Bohemia, about 100 km east of the capital, not far from Kutná Hora. The number of inhabitants is now (2020) around 10,000.

Hašek og Čáslav

Čáslav is not often featured in Hašek's writing. Apart from in The Good Soldier Švejk it is only briefly mentioned in the story Zrádce národa v Chotěboři (The traitor of the nation from Chotěboř).

Demography

According to the 1910 census Čáslav had 9,318 inhabitants of whom 9,119 (97 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Čáslav, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Čáslav. The number of German speakers is low considering that this was a garrision town where 1 205 persons were associated with the army.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Čáslav were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 21 (Časlau) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 12 (Časlau). In 1914 the 2nd batallion of IR. 21 and Ergänzungsbezirk were garrisoned here, whereas regiment staff was located in Kutná Hora. The headcount of these units is however not enough to explain the relatively high military presence. For the numbers to add up k.k. Landwehr must be included. Čáslav was the seat of Landwehrergänzungsbezirk Nr. 12, and in 1914 also hosted k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 12 with all three battalions. That the Landwehr-soldier Švejk talked to in Tábor was from here is therefore logical.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Landverák si odplivl: „U nás v Čáslavi byl jeden redaktor z Vídně, Němec. Sloužil jako fähnrich. S námi nechtěl česky ani mluvit, ale když ho přidělili k maršce, kde byli samí Češi, hned uměl česky.“

Also written:TschaslauReiner/BrousekČaslaude

Literature

- Zrádce národa v Chotěboři, Jaroslav Hašek,10.10.1912

- Válečné děje býv. pěš. pl. 21 čáslavského 1914-1919, ,1936

- Schematismus der k.k. Landwehr (s. 66), ,1914

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 419), ,1914

- Historie čáslavských regimentů,

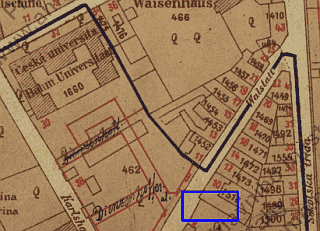

| Na Bojišti |  | |||||

| |||||||

Na Bojišti in 1884, U kalicha is yet to be built.

Na Bojišti is mentioned by Švejk in the conversation with the lieutenant at Tábor station who accuses him of being degenerated.

Background

Na Bojišti is a street in Praha II. that in the mid 19th century was known as Windberg. It was surrounded by fields and gardens, only 3-4 houses can be seen. By 1875 maps show many additional buildings and a street now called Wahlstatt, a name that corresponds to the street's current name (Battlefield). The building U kalicha was amongst the last to be built. It is not on the map from 1884, but by 1889 it has appeared.

In number 463/10 lived in 1912 some Josef Švejk and he was a person Jaroslav Hašek may have known about when he wrote the novel. In the same house Antonín Nosek ran a brothel (1912), and this may explain why the good soldier told Sappeur Vodička that they have girls at U kalicha.

From 1876 onwards the street is repeatedly mentioned in the press, albeit in minor headlines. In the years before 1900 several suicides are reported. An article in Prager Tagblatt in 1885 mentions the poor hygienic conditions, and several cases of typhus. In 1914 the same newspaper reports that the police are making an effort to limit street prostitution. In 1915 small adverts reveal than many Jewish refugees from Galicia rented rooms in the street, particularly in no. 8 and 10. Incidentally many rooms and flats were for rent here also before the war.

There is every indication that Švejk lived in or near this street - both because he was a regular at U kalicha and that he says "by us" at the corner of Bojistě and Kateřinská ulice.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Tyto úvahy shrnul v jednu větu, s kterou se obrátil k Švejkovi: „Vy jste, chlape, degenerovanej. Víte, co je to, když se o někom řekne, že je degenerovaný?“ „U nás na rohu Bojiště a Kateřinský ulice, poslušně hlásím, pane lajtnant, byl taky jeden degenerovanej člověk. Jeho otec byl jeden polskej hrabě a matka byla porodní bábou. Von met ulice a jinak si po kořalnách nenechal říkat než pane hrabě.“

[II.4] Když se Švejk s Vodičkou loučil, poněvadž každého odváděli k jejich části, řekl Švejk: "Až bude po tý vojně, tak mé přijel navštívit. Najdeš mé každej večer od šesti hodin u Kalicha na Bojišti."

[IV.3] „To toho moc neumíš,“ řekl k němu Švejk. „Na Bojišti bydlel v jednom sklepním bytě metař Macháček, ten se vysmrkal na vokno a rozmazal to tak dovedně, že z toho byl obraz, jak Libuše věští slávu Prahy.

Also written:Wahlstattde

Literature

- Selbstmord, ,29.7.1881

- Sanitäts-Spaziergange, ,26.7.1885

- Stehlíkův historický a orientační průvodce ulicemi hlavního města Prahy, ,1929

| Kateřinská ulice |  | ||||

| ||||||

7.12.1904 • Celkový pohled na dům čp. 522 na nároží Ječné a Kateřinské ulice na Novém Městě.

© AHMP

Kateřinská ulice is mentioned by Švejk in the conversation at Tábor station where the lieutenant accuses him of being degenerated. Švejk refers to it by saying "by us at the corner of Kateřinská and Bojiště".

Background

Kateřinská ulice is a street in Nové město, Prague. This is also the location of Kateřinky, the madhouse where Švejk spent some time early in the novel. The text indicates that Švejk lived in or near this street, but referring to the corner with Na Bojišti makes no sense, as the two streets don't join. Švejk may have meant the corner of Ječná ulice and Sokolská ulice where the author lived for a short period in 1888 and 1889.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Tyto úvahy shrnul v jednu větu, s kterou se obrátil k Švejkovi: „Vy jste, chlape, degenerovanej. Víte, co je to, když se o někom řekne, že je degenerovaný?“ „U nás na rohu Bojiště a Kateřinský ulice, poslušně hlásím, pane lajtnant, byl taky jeden degenerovanej člověk. Jeho otec byl jeden polskej hrabě a matka byla porodní bábou. Von met ulice a jinak si po kořalnách nenechal říkat než pane hrabě.“

Literature

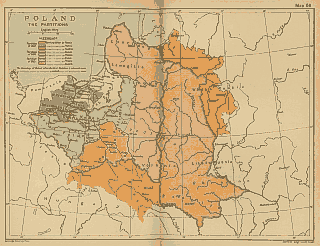

| Poland |  | |||

| |||||

Poland with borders from 1772 and after the partitions 1772, 1793 and 1795.

Poland is mentioned indirectly through a Polish count. This happens when Švejk is accused by the lieutenant in Tábor of being degenerated. He retorts with an anecdote about the degenerate son of a Polish count who lived "by us" at the corner of Kateřinská ulice and Na Bojišti.

As the plot progresses in part III and IV more Poles are mentioned, for instance the "latrine general" in Budapest and a soldier from Kołomyja who messed with the field password. As the march company moves onto Polish territory by the Łupków Pass even more Poles appear, mostly without being mentioned by name. Examples are the spy in Švejk's cell in Przemyśl and the Polish head teacher in Klimontów.

The final four chapters of the plot of The Good Soldier Švejk takes place in current south-eastern Poland and in eastern Galicia, an area where Polish was the principal official language. On the current territory of Poland Švejk visited the Łupków Pass, Szczawne, Kulaszne, Sanok, Tyrawa Wołoska, Liskowiec, Krościenko and Przemyśl. Numerous other places are mentioned, amongst them Kraków, Warsaw, Poznań and Częstochowa.

In contrast to the many geographical references remarkably few Polish persons are mentioned by name, the only obvious one being Mr. Grabowski (the author surely meant Dworski). Trainsoldat Trainsoldat Bong may also have been Polish but this has not been verified.

Background

Varšava zámek

,14.10.1914

Poland was in 1914 not an independent state as Polish lands had for almost 120 years been split between Austria, Germany and Russia. Despite the adversity Polish culture, language and nationhood rule had survived foreign rule. The background was three territorial divisions of Poland (1772, 1793, 1795), perpetrated by Russia, Prussia and Austria, by which Poland's size was progressively reduced until, after the final partition, the state ceased to exist. In 1918 the independent Polish state finally resurfaced, resulting from the defeat in World War I of the three powers that until then had ruled the country.

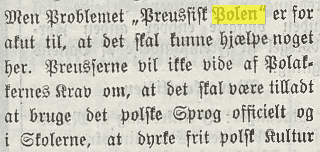

Russian and German Poland

The largest part of Poland was under Russian rule, from 1815 known as the Kingdom of Poland (Królestwo Polskie, Царство Польское) with the tsar as a nominal king and Warsaw as capital. Formally it enjoyed widespread autonomy but this was gradually eroded, particularly after the uprisings in 1830 and 1863. Further Russification measures followed, for instance the introduction of Russian as an official language after 1860. By 1900 the number of inhabitants was almost 10 million and Warsaw was the third largest city in Imperial Russia. Russian rule continued until 1915, ended by the Central Power's military victories that year. Poles served in the Russian army. An example is the battle by Sokal in July 1915 where Polish units faced Jaroslav Hašek's IR. 91 and distinguished themselves. ,7.9.1910

German Poland consisted mainly of the Prussian province of Posen (Prowincja Poznańska, Provinz Posen) and was with 2 million inhabitants (1910) much smaller than Russian Poland. Poles made up two thirds of the population but had little influence on governance. Like in Russia Polish culture and language were subjugated and the province was subjected to severe Germanisation, particularly during and after Bismarck's reign. On the other hand Posen was the most prosperous of the areas populated by Poles. They were however obliged to serve in the German Imperial army.

Austrian Poland

,29.6.1914

When Poland and Poles is a theme in The Good Soldier Švejk it is overwhelmingly likely to refer to Poles in Austria, for all practical purposes Galicia (Galicja - Galizien). It was annexed by Austria after the first partition of Poland in 1772. Poles in Austria enjoyed far greater autonomy than their brethren in Russia and Germany. From 1873 Galicia became an autonomous province of Cisleithania with Polish and, to a lesser degree, Ruthenian (Ukrainian)[1], as official languages. The Galician Sejm (parliament) and provincial administration had extensive privileges and powers, especially in education, culture, and local affairs. The Polonisation of autonomous Galicia came at the expense of the Ukrainians and also the much smaller German minority. Dissatisfaction with Polish rule led to a strong Russophile movement amongst the Ukrainian population, a theme touched upon also in The Good Soldier Švejk. Poles, as one of the 11 nations of Austria-Hungary, made up almost 10 per cent of the 52 million strong population (classified by language). In the Reichsrat lower chamber they had 82 out of 516 representatives (1911).

In 1910 the population was around 8 million and the capital was Lwów. Galicia was ethnically divided with Poles being the majority in the west and Ukrainians in the east. The exception was Lwów where Polish speakers formed a majority in an otherwise Ukrainian region. Poles made up 58 per cent of the population, Ukrainians 40 per cent. Jews were not classified as a nation in Austria-Hungary but the confession statistic reveal that they numbered 11 per cent the population of Austrian Poland.

During the war

Lage und Verteilung der Kräfte 1. Mai 1915. Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg II, Beilage 15.

During 1914 and 1915 fierce fighting took place on Polish territory. Austro-Hungarian troops invaded Russian Poland in August and enjoyed early success in the battles of Kraśnik and Komarów. These advances were however overshadowed by the disaster in Galicia where the capital Lwów was abandoned in early September and k.u.k. forces were pushed back to the river San and the Carpathians. The situation was particularly critical in late November when the Russian 3rd Army crossed the Raba and threatened Kraków. Their advance was however halted during the battle of Limanowa and the front was stabilised along the Dunajec and the Carpathians. Of particular significance was the fortress of Przemyśl that tied up large Russian forces until it capitulated on 22 March 1915 after having been encircled since 8 November 1914. Further north the German army was more successful and by January 1915 it had occupied parts of Russian Poland, including the large city of Łódź.

In early may 1915 a major turnaround occurred. The Central Powers launched a successful offensive by the Dunajec that forced the Russians away from the Carpathians and during the summer forced them out of virtually all of Poland. Warsaw fell on 4 August 1915 and in addition nearly the entire Galicia was back in Austrian hands by the autumn.

As opposed to the Czechs and Ukrainians the Poles remained relatively loyal to Austria-Hungary during the war (and incidently also to Germany and Russia in their respective parts). The Central Powers even agreed to create a puppet state called the Kingdom of Poland on former Russian territory and a Polish Legion led by future president Józef Piłsudski was created as a semi-autonomous unit under the auspices of k.u.k. Wehrmacht.

Hašek in Poland

Jaroslav Hašek, Zakopane, 6.8.1901

It is documented that Jaroslav Hašek (who knew some Polish) visited Austrian Poland in 1901 and 1903. The sources are his own post cards and also a police report after his arrest in Kraków in July 1903. He also wrote some stories from western Galicia that are set in the area by the rivers Raba and Dunajec. In the stories Mezi tuláky and Procházka přes hranice[2] he wrote that he by mistake crossed Russian border, was arrested and brought to Kielce in Russian Poland but soon dispatched across the border to Kraków. No independent accounts can however verify this story but the topographical description is quite accurate so the story may well be based on his own experiences.

Hašek also visited the territory of current Poland when he was transported with his march battalion to the front in the early days of July 1915. This was however nothing more than a transit by train[3] and it can practically be ruled out that he ever visited Sanok and Przemyśl, the two Polish mainstays of the plot. The route described in [III.4] Marschieren Marsch!", Sanok - Felsztyn, is also a result of artistic license. The plot of this chapter may well have been inspired by the author's own experiences in 1915 but not within the geographical conext he uses in the novel.

In the Ukrainian part of Galicia he did however spend much more time: from 4 July to 27 August 1915, now as a soldier with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91.

Švejk's stronghold

18. Manewry Szwejkowskie, Przemyśl, 3.7.2015

Poland is today a world leader in the effort to keep Švejk's name alive and they even surpass the Czech Republic in this respect. The soldier has inspired groups of admirers in several locations, with annual Švejk festivals in both Kielce and Przemyśl. The latter is the largest event and has long traditions. The festival Manewry Szwejkowskie takes place in early July every year and in 2022 it was arranged for the 25th time. Poland also boasts some prominent švejkologists, first and foremost Antoni Kroh. He is not only the translator of The Good Soldier Švejk - he has also written a thorough and well researched book about the theme (O Szwejku i o nas, 1992). The explanations published in his translation are similarly informative and solid. On the itinerary that Švejk followed has been created a tourist trail with yellow explanatory posters (Szlak Dobrego Wojaka Szwejka). Sanok, Przemyśl and Kielce both have statues of the good soldier and there are several Švejk-restaurants around Poland.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.1] Tyto úvahy shrnul v jednu větu, s kterou se obrátil k Švejkovi: „Vy jste, chlape, degenerovanej. Víte, co je to, když se o někom řekne, že je degenerovaný?“ „U nás na rohu Bojiště a Kateřinský ulice, poslušně hlásím, pane lajtnant, byl taky jeden degenerovanej člověk. Jeho otec byl jeden polskej hrabě a matka byla porodní bábou. Von met ulice a jinak si po kořalnách nenechal říkat než pane hrabě.“

Also written:PolskoczPolendePolskapl

| 1. | In official Austro-Hungarian terminology Ruthenen referred to the Ukrainian population of the empire. On this page the terms "Ruthenian" and "Ukrainian" are therefore interchangeable. |

| 2. | "Amongst tramps" and "A stroll across the border". |

| 3. | According to Jan Vaněk the march battalion were in Humenné on 2 July 1915 and two days later their train had halted near Sambor. The route would have been across Łupków Pass and down to Zagórz by Sanok, then to Sambor via Chyrów and Felsztyn. |

Literature

- Russian Partition,

- Prussian Partition,

- Austrian Partition,

- Poland, Piotr Szlanta,8.10.2014

- Oj Dunajec biala wôda..., Jaroslav Hašek,10.2.1902

- Jak se stareček Perunko věšel, Jaroslav Hašek,8.7.1903

- Vypomínka na močálů, Jaroslav Hašek,24.7.1903

- Po třicíti letech, Jaroslav Hašek,8.10.1903

- Chalute, Dr. Stanko,1.1907

- Pan Lazar Adamus z Jarochówa, Jaroslav Hašek,23.6.1907

- Židovská povídka ze Zapustny v Haliči, Jaroslav Hašek,5.7.1908

- Mezi tuláky, Jaroslav Hašek,18.5.1905

- Ve vesnici u řeky Rábu, Jaroslav Hašek,25.9.1908

- Procházka přes hranice, ,1915

|

II. At the front |

| |

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |