Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

10. Švejk as a military servant to the field chaplain | |||

| Česká strana národně sociální |  | |||

| Praha II./739, Dlouhá tř. 27 | |||||

| |||||

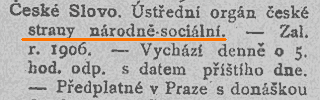

The first party newspaper, one month after the party was founded

,9.1.1909

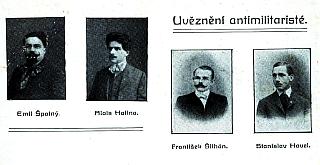

Imprisoned anti-militarists, 1909

© Národní archiv - Archiv České strany národně sociální

,25.6.1909

, 1910

Česká strana národně sociální is indirectly mentioned when one of the soldiers in Švejk's escort on way from Hradčany to Karlín asks him if he is a national socialist.

Background

Česká strana národně sociální (Czech National Social Party) was a political party that was founded in April 1897 as a break-away group from the Social Democrats and some defectors from Mladočeši. The split came about mainly because the mother party advocated working within Cisleithania as a whole, whereas the splinter group advocated state rights for the Czech Lands. The relatively large number of Jews in the mother party also played a part in provoking the break. Their political platform was roughly based on reform socialism, radical nationalism, and anti-militarism. They were also strongly anti-clerical, anti-German, promoted use of the Czech language in the public sector. The party was often referred to as "Czech Radicals". The party chairman from 1898 to 1938 was Klofáč.

The first who printed Švejk

It may, at first sight, appear odd the so much space is dedicated to the party, but in a Švejk context, there are two reasons for doing so. It was the party's own press who printed the first three stories about Švejk in 1911 (Karikatury, Josef Lada), and their principal mouthpiece České slovo was one of the main promoters of The Good Soldier Švejk after the author's death. Hašek was also shortly employed by this paper both in 1908 and 1912 and also contributed in other periods. He was a personal friend of several of the newspapermen who served the party press, and Hašek as a nationalist and socialist was no doubt ideologically close to the party.

Pre-war period

But now back to the party proper... At the 1911 election to Reichsrat the party achieved 9.7 per cent of the votes in Bohemia and had 15 representatives. In Moravia the party was much weaker and had only one representative.

Already from the beginning, Staatspolizei kept a keen eye on the party. Under particular scrutiny was the youth organisation and their newspaper Mladé proudy, led by Emil Špatný and Alois Hatina.

The agent Mašek

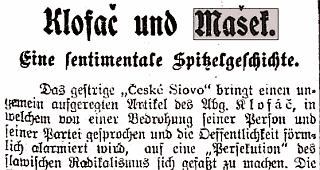

On 8 January 1909 party chairman Klofáč claimed in České slovo that an agent provocateur in the service of the police had tried to incriminate the party with highly treasonous fabricated material connecting them to Serbia. A key person in this plot was Hynek Mašek, a well-known adventurer and deceiver who the police already had employed to spy on politically suspect groups like the anarchists. According to Klofáč he was paid by Oberkommisar Chlum in Staatspolizei. Klofáč took the case as a matter of urgency to Reichsrat where he demanded Mašek be arrested and a stop to the illegal activities of the police. The thunderous debate took place on 12 March, but the case was rejected.

Klofáč never managed to prove the allegations, and in parts of the German language press it was ridiculed as a "romantic spy novel". The Czech newspapers were more accomodating but Čas, the paper of Professor Masaryk's Realist Party, commented in a terse and realist way that "the police have a strange connection both to the National Social party and to Hynek Mašek. No less, no more." That said many of the allegations were no doubt true, and none of them can be directly disproved.

Antimilitarist process

The youth organisation increasingly became a thorn in the eye of the authorities, mainly because they started to agitate and spread propaganda even within k.u.k. Wehrmacht, disturbing the draft process etc. In 1909 a court case against 46 of their leaders was instigated. In the first trial, only a few were convicted, but after an appeal by the state attorney, almost all of them were sentenced in 1910. The longest sentences handed out were two years. Again the name Hynek Mašek appears, and Hašek mentions both him and the trial in his feulleton Po stopách státní policie v Praze (On the tracks of the state police in Prague), Jaroslav Hašek, Čechoslovan, 21 August 1916.

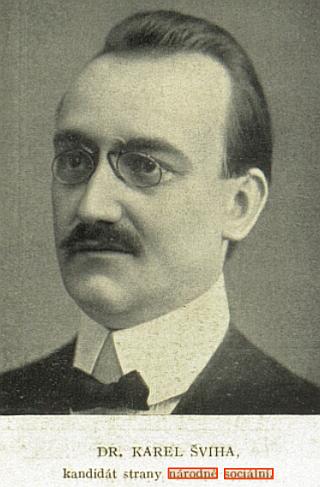

The Šviha affair

In the spring of 1914, the party was hit by a scandal of far greater dimensions. The chairman of the party's group in parliament, Karel Šviha, was revealed to be linked to k.u.k. Staatspolizei and as usual when this unit was mentioned, the names Mr. Klíma and Mr. Slavíček appear. Šviha was forced to resign and the scandal signalled the end to his political career.

Banned and persecuted

In 1914 the party was banned and the leaders were arrested, and two party members were executed (editor Kotek and Slavomír Kratochvíl) in November 1914. Klofáč was spared the same fate by the 1917 amnesty issue by the new emperor Karl I.

After the war

In 1918 the party was renamed the Czechoslovak Socialist Party and in 1926 even the National Socialist Party! Their best known public profile after the war was without doubt Eduard Beneš who joined in 1923. The party was during the inter-war years member of the five-party ruling coalition. It was brutally persecuted during Nazi rule and in 1948 it was swallowed up by the communists and became their puppet party. It reappeared after the 1989 Velvet Revolution but with a dwindling number of votes, high debts, and frequent name changes, the party is now for all practical purposes non-existing.

National Socialist

The term "National Socialist" was, as the novel reveals, already used in daily speech already before World War I, but was obviously not related to the notorious Nazi party that emerged in Germany after the war. Although the two parties shared fervent nationalism, anti-Semitism and certain aspects of economic policies, the differences were much more notable.

The Czech national socials didn't seek to overthrow the democratic system, didn't persecute their opponents and were openly anti-militarist. Nor did they share the Nazi party's hatred of Communism or their ideas on racial hygiene. Whereas the Czech party's nationalism was a reaction to external threats to national culture and self-determination, their German namesake was driven by aggressive ambitions to expand at the expense of other nations.

Hašek and the party

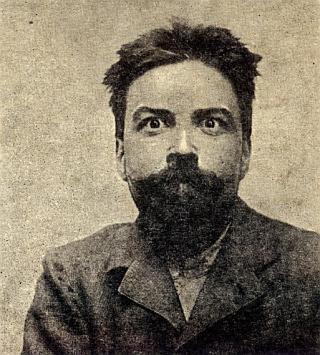

Emil Špatný, friend of Hašek - during a razzia on 27 March 1909 he swallowed a compromising letter!

© Národní archiv - Archiv České strany národně sociální

Jaroslav Hašek was a personal friend of several members of the national social youth organisation, amongst them Alois Hatina and Emil Špatný. Both were editors at the newspaper Mladé proudy, and like Hašek they were at the time close to the anarchists. If Hašek ever was a party member is not clear, but we know that he assisted during election campaigning in 1908 (Radko Pytlík).

Nor was he a stranger to the party's official newspaper České slovo and the leadership of the party proper. Several party leaders and newspapermen are mentioned in his various stories. Klofáč himself appears in The Good Soldier Švejk and features in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona and elsewhere. Otherwise, Karel Šviha, Jiří Škorkovský and many others fell victim to the satirist's sharp pen.

České slovo

České slovo (The Czech Word) was founded in 1907 and Hašek's first story appeared in their columns on 28 June 1908 and he had altogether eleven stories printed in the paper that year. In 1909 his name disappeared, but in 1911 and 1912 there was some scattered activity.

Hašek briefly worked for České slovo as a local reporter in 1912 but was soon dismissed. At the height of the Šviha affair in March 1914, he wrote a stinging obituary over the party in Kopřivy, a satirical magazine associated with the rival Social Democrats!

The publishing house Melantřich was closely linked to the party, and apart from České slovo they published a number of smaller newspapers and magazines. One of them was Karikatury, a satirical magazine edited by Hašek's friend Josef Lada. It was on their pages that The Good Soldier Švejk appeared for the first time, on 22 May 1911.

Following Hašek's return from Russia, a new period of intense activity in the columns of České slovo followed. The first story appeared already on 5 January 1921 and several more followed that spring. They mostly appeared in the evening paper Večerní České slovo.

After Hašek's death, České slovo played a prominent role in popularising his novel. From 11 November 1923 onwards they published Josef Lada's famous drawings that colour our perception of Švejk even until today. In the autumn of 1924, the evening paper printed the first serious study of the links between Hašek's own experiences in k.u.k. Heer and the plot of the novel. See Jan Morávek for more details on this theme.

The letter that was swallowed

,29.3.1909

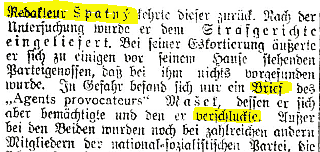

As a side note we have also made the following observation: One of Hašek's friends from the party may well have inspired one of the most memorable episodes from Švejk's stay in Királyhida. On 27 March 1909 the police carried out a house search at the homes of various members of Česká strana národně sociální. One of the subjects of the razzia was the aforementioned editor Emil Špatný. He showed himself to be very alert - and allegedly tore up and swallowed a compromising letter from the agent provocateur Hynek Mašek! The episode was reported in several papers, amongst them Prager Tagblatt[a] and Neue Freie Presse.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Nejsi národní socialista?“ Nyní počal být malý tlustý opatrným. Vmísil se do toho. „Co je nám do toho,“ řekl, „je všude plno lidí a pozorujou nás. Aspoň kdybychom někde v průjezdu mohli sundat bodla, aby to tak nevypadalo. Neutečeš nám?

Credit: Svatopluk Herec

Also written:Czech National Social PartyenTschechische national-soziale ParteideDet tsjekkiske nasjonalsosiale partino

Literature

- Exploring the Nature of Nationalism and Socialism in Czech National Socialism, ,2008

- Vztah národně sociální strany a národně sociální mládeže v letech 1901 - 1910, ,2014

- Politický klub "Osvěta" strany národně sociální, ,1910

- Historie ČSNS,

- Odboj sociálních demokratů proti Českému státu, ,8.4.1897

- Klofač und Mašek, ,9.1.1909

- Grosse Sturmszenen in Abgeordnetenhause, ,10.3.1909

- Die antimilitaristische Propaganda, ,29.3.1909 [a]

- Persekuce strany národně-sociální za války, ,1921

- Jak jsem vystoupil ze strany Nár. sociální, Jaroslav Hašek,14.3.1912

- Hrst nezabudek, sázených na hrob strany národně sociální, Jaroslav Hašek,26.3.1914

- Po stopách státní policie v Praze, Jaroslav Hašek,21.8.1916J

| a | Die antimilitaristische Propaganda | 29.3.1909 |

| Na Kuklíku |  | |||||

| Praha II./1130, Petrské nám. 6 | |||||||

| |||||||

,16.12.1923

,20.5.1901

Na Kuklíku was the tavern where Švejk and his guards had a long and happy break before they, under the influence, continued to Feldkurat Katz in Karlín. A certain pubkeeper Serabona is reported to be the landlord, and as a member of Sokol he can be trusted.

Background

Na Kuklíku was a restaurant in Prague at Petrské náměstí. Newspaper adverts from 1877 reveal that the pub existed and that they also brewed their own beer. Towards the end of the 1880s brewing appears to have ceased, but the restaurant business continued. According to the 1900 census Gustav Holan was the landlord.

Vilém Srp was granted a license 1901 and was in 1923 still the owner. That year a newspaper report reveals that treasures worth Kč 50,000 had been hidden in the loft but had been stolen at a time when the landlord couple were ill. The culprits were caught and sentenced. It is interesting that a postcard from 1906 reveals that the place was also called U Serabono. See pubkeeper Serabona. The building was demolished in 1928.

Kuklík is mentioned in a story by Egon Erwin Kisch: Zitaten vom Montmartre where it is described as a rough place. Over the years several reports of disturbances appeared in the newspapers. There were incidents involving unruly soldiers, and reported cases of theft and a gang cheating at cards.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Pojďme na Kuklík,“ vybízel Švejk, „kvéry si dáte do kuchyně, hostinský Serabona je Sokol, toho se nemusíte bát. Hrajou tam na housle a na harmoniku,“ pokračoval Švejk, „a chodějí tam pouliční holky a různá jiná dobrá společnost, která nesmí do Represenťáku.“ Čahoun s malým podívali se ještě jednou na sebe a pak řekl čahoun: „Tak tam půjdem, do Karlína je ještě daleko.“ Po cestě jim Švejk vypravoval různé anekdoty a v dobré náladě vstoupili na „Kuklík“ a udělali to tak, jak Švejk radil. Ručnice uschovali v kuchyni a šli do lokálu, kde housle a harmonika naplňovaly místnost zvuky oblíbené písně "Na Pankráci".

[I.10.1] Švejk vzpomínal též na jednoho básníka, který tu sedával pod zrcadlem a v tom všeobecném ruchu „Kuklíku“, zpěvu a pod zvuky harmoniky psával básničky a předčítal je prostitutkám.

[I.10.1] Čahoun byl také toho mínění, že polní kurát může čekat. Švejkovi se však přestalo již na Kuklíku líbit, a proto jim pohrozil, že půjde sám.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák, M. Smreček

Literature

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021

- Bierfasser, ,13.11.1877

- Schlimme Gäste, ,17.5.1879

- Wirtshausexcess, ,13.4.1880

- Lynchjustiz, ,19.10.1898

- Loupežná vražda na Hradčanech, ,29.4.1902

- Podivná historie s dvouzlatnikem, ,25.8.1904

- Pro ty alimenty, ,5.4.1912

| Sokol |  | |||

| Praha II./61, Ferdinandova tř. 24 | |||||

| |||||

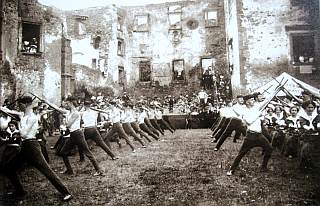

Sokol exercise at Lipnice nad Sázavou castle, some time before 1913

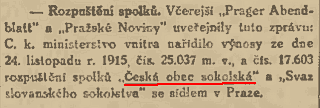

Sokol being dissolved by decree

,30.11.1915

Sokol is briefly mentioned by Švejk when he tells his escort on the way to Feldkurat Katz that the landlord pubkeeper Serabona at Na Kuklíku is a Sokol member and thus no reason to be afraid of. They could without worry leave their rifles in the kitchen and have a drink.

Background

Sokol (Falcon) is a still existing patriotic gymnastics movement founded in Prague in 1862 by Miroslav Tyrš and Jindřich Fügner. They soon became an important part of the Czech national consciousness and also took root amongst other Slav peoples in Austria-Hungary and even in Russia, Serbia and Bulgaria. Throughout the time of the monarchy the authorities kept a close eye on the movement that had strong support from parties that advocated Czech state rights, namely Česká strana národně sociální and Mladočeši. In 1910 the main office was located in Ferdinandova tř. 24, the building has been demolished. The premises are now (2015) occupied by the supermarket Tesco. Scheiner was chairman of both the Czech and the international organisation, and both were located at this address.

On 24 November 1915 the two Prague-based umbrella organisations of Sokol, Česká Obec Sokolská and Svaz Slovanského Sokolstva, were dissolved at the order of the Ministery of Interior. Local organisations were however allowed to function. The official reason for the crackdown was pro-Serbian and pro-Russians activities, anti-Austrian propaganda, and contact with North American Sokol organisation that was very hostile to the ruling dynasty. Sokol leader Scheiner had been arrested already on 25 May. Many Sokol members were indeed active in the Czech resistance movement during the war. Sokol reached its pinnacle during the first republic, but was of course banned by both the Nazis and the Communist.

On 6 January 1923 members of Sokol carried Jaroslav Hašek's coffin to his grave at Lipnice.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí Sokol is mentioned in connection with the interrogation of Švejk at k.u.k. Militärgericht Prag.[1]

Otázky kladou se jen auditorovi, který objasňuje velmi srozumitelně, že obžalovaný je největší lotr na světě, že byl v Sokole, že četl Samostatnost apod.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] „Pojďme na Kuklík“, vybízel Švejk, „kvéry si dáte do kuchyně, hostinský Serabona je Sokol, toho se nemusíte bát. Hrajou tam na housle a na harmoniku,“ pokračoval Švejk, „a chodějí tam pouliční holky a různá jiná dobrá společnost, která nesmí do Represenťáku.

Literature

- Historie Sokola,

- Sokol v dějinách národa,

- Proč byla rozpuštěna Česká Obec Sokolská, ,30.12.1915

- Die amtliche Verstandnis über die Auflösing der Sokolverbande, ,31.12.1915

- Great War and Ban on Sokol,

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

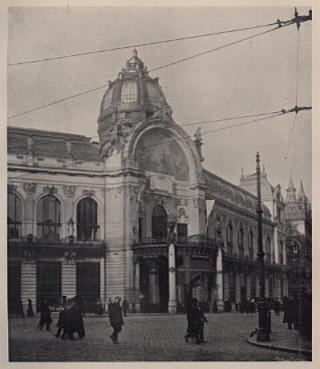

| Reprezenťák |  | ||||

| Praha I./1090, Josefské nám. 4 | ||||||

| ||||||

, 12.1912

Reprezenťák is mentioned when Švejk tells his escort that Na Kuklíku is a pleasant place where street girl and other good company who are not allowed at Reprezenťák may enter.

Background

Reprezenťák is a concert hall and entertainment complex in Prague, now officially called Obecní dům. It was originally known as Reprezentační dům, hence the colloquial term that Švejk uses. It is one of the landmark Art Nouveau buildings in the city. The Czechoslovak independence was proclaimed here on 28 October 1918.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] Hrajou tam na housle a na harmoniku,“ pokračoval Švejk, „a chodějí tam pouliční holky a různá jiná dobrá společnost, která nesmí do Represenťáku.“

Literature

| U Valšů |  | ||||

| Praha I./286, ul. Karoliny Světlé 22 | ||||||

| ||||||

U Valšů, May 2011

,18.9.1910

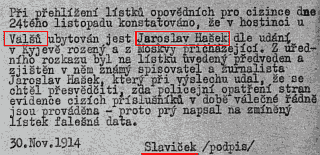

Policejní ředitelstvi, 30.11.1914

U Valšů is referred to in a conversation at Na Kuklíku where it is claimed that a certain Mařka (Marie) had disappeared to U Valšů with a soldier. The place appears again in a story by Švejk on the train after Moson, [III.1].

Background

U Valšů was a coaching inn and hotel in Staré město, from 1908 owned by František Materna[a], a person who may have leant his surname to Einjährigfreiwilliger Materna. It had long traditions and is mentioned in newspapers like Fremden-Blatt as early as 1861[b]. It was still operating in 1917 (the same owner) but seems to have ceased soon after. In 2021 the building housed a theatre.

A legendary hoax

U Valšů was the scene of one of Jaroslav Hašek's most famous hoaxes. On 24 November 1914 he hired a room there, registering as a Russian businessman, born in Kiev, arriving from Moscow. He was soon arrested and taken to c.k. policejní ředitelství. Here he was interrogated by Mr. Slavíček and eventually sentenced to five days in prison. Hašek claimed that the he did it to check how vigilant the security services were! The story soon appeared in newspapers, including the author's humorous response!

Both Václav Menger and Emil Artur Longen mention the episode in their books about Hašek and both brush up the story with dialogues and other details. The police report didn't mention what name Hašek registered under whereas Václav Menger claims it was Ivan Feodorovič Kuzněcov and Longen names him Lev Nikolajevič Turgeněv. Both these versions ought to be read with some scepticism, particularly Longen's. He lets the narrator be some detective Spanda and he even claims that he was the model for detective Bretschneider.

Another version of the story (origin unknown) claims that he registered under a name which backwards read "lick my arse", but this is surely nothing more than a "good story" and is not supported by the police records, nor by Václav Menger nor Longen.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.1] U hudby hádali se dva, že nějakou Mařku včera lízla patrola. Jeden to viděl na vlastní oči a druhý tvrdil, že šla s nějakým vojákem se vyspat k „Valšům“ do hotelu.

Credit: Václav Menger, Emil Artur Longen

Literature

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství, ,1851 - 1914 [a]

- Der Judenkrawall in Prag, ,4.8.1861 [b]

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021

- Jaroslav Hašek, ,1928

- Jaroslav Hašek doma, ,1935

- Přispěvky, ,3.5.1862

- Falešný uprchlík z Ruska, ,13.12.1914

- Humoristovy rozmary, ,18.12.1914

- Laciné noclehy, ,12.6.1919

- Pražské hotely ve světle statistiky, ,10.1.1924

| a | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| b | Der Judenkrawall in Prag | 4.8.1861 |

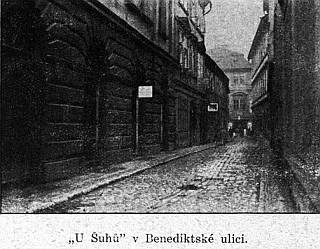

| U Šuhů |  | ||||

| Praha I./722, Benediktská ul. 9 | ||||||

| ||||||

Konec bahna Prahy, ,1927

,2.1.1898

© Milan Hodík

Wo Kafka und seine Freunde zu Gast waren, ,2000

Marriage record,1901

Death record,26.5.1919

U Šuhů was a brothel where Feldkurat Katz owed money, and subsequently didn't want visit any. The place is mentioned twice more: in Part Three in Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek's story about the court of Erzherzogin Marie Valerie and in the story about tinsmith Pimpra.

Background

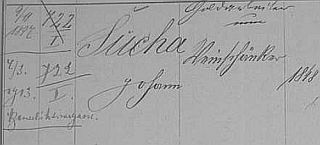

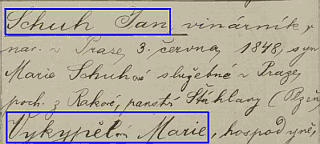

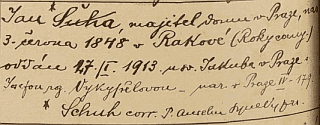

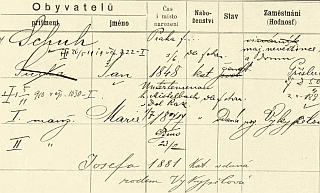

U Šuhů was a brothel in Benediktská 9. According to Chytilův úplný adresář království českého (1913) it was owned by Jan Schuha whom the establishment presumably was named after. In Cecil Parrott's translation of The Good Soldier Švejk, a footnote describes U Šuhů as a "notorious brothel".

Kafka at Šuha's brothel

Feldkurat Katz and tinsmith Pimpra were not the only notabilities who frequented Šuha. In his diary Franz Kafka discretely mentions a visit on 28 September 1911 when he was served by a "Jewess with a narrow face". He also describes the interior in some detail. The brothel's hostess is described in rather unflattering terms[b].

Kafka expert Hartmut Binder provides interesting information in his book Wo Kafka und seine Freunde zu Gast waren. He reveals that Jan Šuha obtained a brothel's license as a reward for acting as a police informer. It was his wife who managed the brothel, an arrangement that was quite common at the time. It is also revealed that Kafka must have visited more than once. After the death of her husband, Mrs. Šuha married Rudolf Kulhánek, the establishment's bouncer.

Newspaper clips

In a newspaper article from 1891 it is revealed that Šuha was a police informer who contributed to the capture of two thieves who attempted to rob a shop in Michle. The article also states that Šuha was 43 years old so he must have been born in 1848.

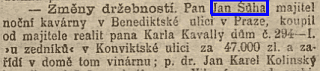

Šuha was already in 1896 listed as proprietor of a wine bar at the above mentioned address, and in 1898 a newspaper clip refers to Jan Šuha, owner of a night café in Benedikstká ulice. That year he bought a café in Konviktská ulice in Staré město. In 1907 (3 April) Architektonický ozbor reported that Šuha had bought house no. 1030 in Benediktská for 96,000 crowns. This was the house on the corner next to the brothel.

In 1923 Národní politika reported of a fight in front of the house, when a drunk man tried to enter a flat because he thought this was where the brothel still was. So Šuha had ceased doing business some time between 1913 and 1923. He had by 1913 reached the age of 65 and in 1919 licensed brothels were made illegal although the ban was later relaxed somewhat.

Police registers

The police registration protocols reveal more. They confirm that Johann Šucha was born in 1848 and that he in 1901 married the 29 years younger Marie Wykypěl. Šuha is listed with two occupations: Goldarbeiter (gold craftsman) and Weinschänker (wine tavern waiter), born and with Heimatrecht in Rakov near Plzeň. On 4 March 1913 they are both entered as residents of Benediktinergasse 722/I. It should also be noted that Emilie Rossmann (born Vykypěl, Brno 1887) is entered at the same address. It is tempting to suggest that she may have been the sister of Marie.

Church records

Research in church records by Jaroslav Šerák (2019) provides more details about the proprietor of the brothel. The files provide birth and death dates, and also information about marriages.

Jan Schuh (name according to birth record) was born outside marriage at Hradčany on 3 June 1848, not in Raková as the police registers show. On 18 April 1901 he married the 23 year old Marie Vykypělová who already then served as "madam" at his establishment. Marie Schuhová died already on 5 November 1910 so she could not have been the brothel madam who Kafka wrote about in his diary a year later (but it may have been her that Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek remembers). On 27 January 1913 Schuh married the younger sister of his late wife, Josefa Vykypělová. She also functioned as madam at the establishment so it was probably her Kafka described. Brothel owner Jan Schuh died on 26 May 1919.

It is also confirmed that Josefa Schuhová shortly after her husband's death married the 8 year younger head waiter at the brothel, Rudolf Kulhánek. Emilie Rossmannová, married to Leopold, was the sister of the two brothel mamas. Josefa Kulhánková died on 5 September 1924, at the age of 43.

Census, 1900

The 1900 census reveals more details (the 1910 census records are not yet available digitally). Šůha owned aprtment number 19 and 20, and altogether 15 persons lived there. Apart from they owner they were the waitress (Marie Vykypěl) and two more waitresses/servants (Josefa Vykypěl and Anna Vlachovská). In addition there were 11 prostitutes where the two youngest were 15 and the oldest 23! Everyone in the flats reported Czech as their common speech[a].

Franz Kafka, Diaries, 1 October 1911

In B. Suha two days before yesterday. The sole Jewess with a narrow face, continuing in a narrow chin, but with an extensively wavy and broad hair style . The three small doors leading from the interior of the building to the hall. Guests like in a guard house on the stage, drinks on the table, but are hardly touched. The woman with the flat face in a square dress that begins to move only deep down below the seam. Now, as before, some are dressed like puppets for a children’s theatre, as one sells them on the Christmas market, i.e. covered with ruffles and gold and loosely sewn, so that they can be separated in one go and they fall apart between one’s fingers. The hostess with the light blonde and tightly pulled hair, no doubt covering a disgusting foundation, with sharply declining nose, whose direction has some geometric relation to the sagging breasts and the tightly strung belly, complains of a headache, which is caused by the fact that today, Saturday, there was great hype but nothing to it.

Franz Kafka, Tagebücher, 1. Oktober 1911

Im B. Suha vorvorgestern. Die eine Jüdin mit schmalem Gesicht, besser das in ein schmales Kinn verlauft, aber von einer ausgedehnt welligen Frisur ins Breite geschüttelt wird. Die drei kleinen Türen, die aus dem Innern des Gebäudes in den Salon führen. Die Gäste wie in einer Wachstube auf der Bühne, Getränke auf dem Tisch, werden ja kaum angerührt. Die Flachgsichtige im eckigen Kleid, das erst tief unten in einem Saum sich zu bewegen anfängt. Einige hier und früher angezogen wie die Marionetten für Kinderteater, wie man sie auf dem Christmarkt verkauft d.h. mit Rüschen und Gold beklebt und lose benäht, so daß man sie mit einem Zug abtrennen kann und daß sie einem dann in den Fingern zerfallen. Die Wirtin mit dem mattblonden über zweifellos ekelhaften Unterlagen straff gezogenem Haar, mit der scharf niedergehenden Nase, deren Richtung in irgendeiner geometrischen Beziehung zu den hängenden Brüste und dem steif gehaltenen Bauch steht, klagt über Kopfschmerzen, die dadurch verursacht sind, daß heute Samstag ein so großer Rummel und nichts daran ist.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Polní kurát pustil se vrat a navalil se na Švejka: „Pojďme tedy někam, ale k Šuhům nepůjdu, tam jsem dlužen.“

[III.3] Kvůli pořádku, aby si snad dvorní lokajové nedovolili nějaké důvěrnosti ku dvorním dámám přítomným na hostině, objevuje se nejvyšší hofmistr baron Lederer, komoří hrabě Bellegarde a vrchní dvorní dáma hraběnka Bombellesová, která hraje mezi dvorními dámami stejnou úlohu jako madam v bordelu u Šuhů.

[III.4] Švejk velice vážně a důrazně řekl: „Nic jste neprováděl, pane lajtnant, byl jste jenom na návštěvě v jednom vykřičeným domě. Ale to byl asi nějakej vomyl. Klempíře Pimpra z Kozího plácku taky vždycky hledali, když šel kupovat plech do města, a našli ho také vždycky v podobnej místnosti, buď u ,Šuhů’, nebo u ,Dvořáků’, jako já vás našel.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák, Franz Kafka, Hartmut Binder, K.L. Kukla

Also written:Schuhade

Literature

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství, ,1851 - 1914

- Sčítání lidu Praha I., ,1900 [a]

- Adressář královského hlavního města Prahy a sousedních obcí, ,1896

- Krádež pod dozorem konfidentů, ,16.4.1891

- Změny držebnosti, ,2.1.1898

- Spletl si to, ,13.4.1923

- Tagebücher, Heft 1, ,1.10.1911 [b]

| a | Sčítání lidu Praha I. | 1900 | |

| b | Tagebücher, Heft 1 | 1.10.1911 |

| Korpskommando |  | ||||

| Praha III./258, Malostranské nám. 15 | ||||||

| ||||||

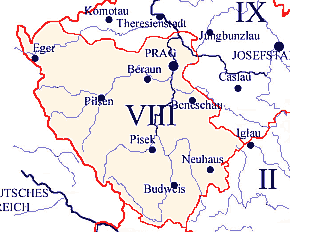

The recruitment area of the 8th Corps

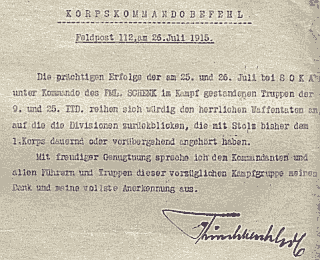

Korpskommando at Sokal. Signed von Scheuchenstuehl.

Korpskommando is mentioned by Feldkurat Katz in his drunken stupor on the way back from Oberleutnant Helmich's party.

Background

Korpskommando here refers to the 8. Korpskommando, one of a total of 16 army groups in Austria-Hungary. The corps, with headquarters in the Lichtenstein Palace in Malá Strana recruited from south, west and central Bohemia. Together with 9. korps (Litoměřice) it covered all of Bohemia.

Subordinated the corps were these units: 9. Infanteriedivision (with IR. 91), 19. Infanteriedivision, L21. Infanteriedivision, 8. Feldartilleriebrigade, 1. Kavaleriebrigade and Traindivision Nr. 8. Corps commander in 1914 was general Artur Giesl von Gieslingen. After the failure in Serbia in 1914 he was replaced by Viktor von Scheuchenstuel.

Employed at the corps command was also the master-spy Alfred Redl, chief of their general staff from 18 October 1912. In May 1913 his activities were uncovered: he had been spying for Russia for around 10 years. He is regarded as one of the best (worst) spies ever, and handed over whatever existed of value.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Polní kurát, který zaslechl poslední slova, pobručuje si nějaký motiv z operety, kterou by nikdo nepoznal, vztyčil se k divákům: "Kdo je z vás mrtvej, ať se přihlásí u korpskomanda během tří dnů, aby mohla být jeho mrtvola vykropena."

Literature

| Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 |  | ||||

| Salzburg | ||||||

| ||||||

,1908

Town square in Jindřichův Hradec

Lehener Kaserne, Salzburg

,1914

,8.8.1914

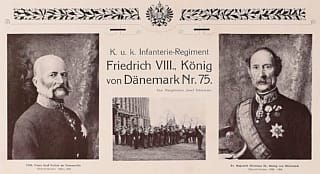

Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 is mentioned in passing when the inebriated Feldkurat Katz in the cab home from Oberleutnant Helmich mistakes Švejk for Oberst Just from the 75th regiment.

The regiment is mentioned again when Feldkurat Katz and Švejk have to borrow a trophy from Oberleutnant Witinger for their field mass in [I.11].

In [II.3], on the train to Bruck Švejk mentions Korporal Rejmánek from this regiment in an anecdote. A member of the escort adds more anecdotes that are related to the regiment, for instance from Serbia. In the next chapter Oberst Schröder mentions the regiment when he tells Oberleutnant Lukáš about his experiences by the front south of Belgrade. See II. Marschbataillon.

Background

Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 was one of 102 Austro-Hungarian infantry regiments. It was founded in 1860 and had their baptism of fire already in 1866 at the second battle of Custoza.

It was a predominantly Czech regiment, recruited from Heeresergänzungsbezirk Nr. 75, Jindřichův Hradec (Neuhaus). The Ergänzungsbezirkskommando and 3rd battalion were located here in 1914. The staff and the other three battalions had been garrisoned in Salzburg from March 1912. In Salzburg they raised some attention with their Czech songs, and are said to have caused a boom in the local interest in football.

Regimental commander was colonel Franz Wiedstruck. The regiment had previously been moved around; between 1906 and 1909 in Prague, at Hradčany. Then it moved to Jindřichův Hradec where it remained until the 1912 transfer.

During the war

Already on 5 August 1914 the regiment departed for the front against Russia. They were allocated to the 4. Armee and in 1914 the fought mostly in the area between the river San and Kraków. In the new year they were transferred to the German Süd-Armee and moved to the area east of Munkács. The regiment remained on the eastern front until September 1917 when they were transferred to Tyrol [d].

Zborów

The regiment received particular attention after the battle of Zborów on 2 July 1917. On this day many of the regiment's soldiers were taken prisoners by their own countrymen from the Legions and accusations of treason led to investigations in Vienna and the case was brought up in Reichsrat.

Ersatzbataillon

The replacement battalion was in November 1915[a] relocated to Debrecen where they remained until the end of the war[b]. The unit that replaced them in Jindřichův Hradec was Infanterieregiment Nr. 101 from Hungarian Békéscsaba[c].

Oberst Schröder

In a historical context it is obvious that Oberst Schröder and other figures from The Good Soldier Švejk who claimed that the regiment fought in Serbia are mistaken. See II. Marschbataillon.

Gott strafe England

The regiment is also mentioned in Jaroslav Hašek's polemic story Gott strafe England[e]. In this story the main character Hauptmann Adamička turns insane, is transferred to Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 and is taken prisoner at Zborów. The real Josef Adamička however never served in the regiment - and he was stationed in Belgrade at the time the battle was fought.

Wehrgeschichte Salzburg (Erwin Niedermann):

Auf Wunsch des Erzherzog-Thronfolgers Franz Ferdinand (1863– 1914), der in Blühnbach das Jagdschloß besaß, sollten beim zumeist nur deutschsprachigen Militär in Salzburg aber auch Angehörige einer anderen Sprache des multinationalen und multikulturellen Reiches den (ab 1908) zweijährigen Wehrdienst ableisten, so wie das längst in den anderen Kronländern üblich war. So wurden anstelle der „Rainer“ (es verblieb nur das 4. Bataillon) der Regimentsstab und drei Bataillone des Böhmischen Infanterie-Regimentes Nr. 75 aus Neuhaus/Jindrichuv Hradec (lichtblaue Aufschläge, weiße Knöpfe, 79 Prozent tschechische Umgangssprache, 20 Prozent deutsche,1 Prozent verschiedene) mit März 1912 hierher transferiert, wobei ein Bataillon auch in die Lehener Kaserne kam, die anderen zwei in die Franz Josef-Kaserne, bzw. Hofstall-Kaserne und Nonntalerkaserne, die „Rainer“ in die Hellbrunner-Straße, bzw. auf die Festung. Die Salzburger sollen sehr unverständig erstaunt gewesen sein über die in und außer Dienst gesungenen tschechischen Volkslieder der Soldaten, wie mehrfach überliefert wurde.

Die Soldaten dieses IR 75 sollen bereits vor dem Krieg sich für Fußball interessiert haben. Soldaten dieses Regimentes haben vermutlich den Fußball-Boom in Salzburg ausgelöst. Im Mai 1914 wurde im Rahmen eines Militärsportfestes ein Fußballspiel am Exerziergelände der Hellbrunner-Kaserne abgehalten. Salzburger Realschüler spielten gegen Soldaten des IR 75. Die Realschüler schlossen sich dann zu einem Fußballverein “Die Athletiker” zusammen, aus dem der “Erste Salzburger Athletiker-Klub (1.SAK 1914) entstand. Eine weitere Information dazu spricht von der Landwehr Nr.8 in der Hellbrunner-Kaserne, in der Fußball-Spieler aus den böhmischen Mannschaften SLAVIA und SPARTA als Soldaten Dienst versahen.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Švejk ho vzbudil a za pomoci drožkáře dopravil do drožky. V drožce polní kurát upadl v úplnou otupělost a považoval Švejka za plukovníka Justa od 75. pěšího pluku a několikrát za sebou opakoval: „Nehněvej se, kamaráde, že ti tykám. Jsem prase.“

[I.11] Tak dostaneme sportovní pohár od nadporučíka Witingra od 75. pluku. On kdysi před lety běhal o závod a vyhrál jej za ,Sport-Favorit’. Byl to dobrý běžec. Dělal čtyřicet kilometrů Vídeň-Mödling za 1 hodinu 48 minut, jak se nám vždycky chlubí. Jsem hovado, že všechno odkládám na poslední chvíli. Proč jsem se, trouba, nepodíval do té pohovky.“

[II.3] Potom ještě vím o jednom kaprálovi od pětasedmdesátejch, Rejmánkovi...“

[II.3] „U pětasedmdesátýho regimentu,“ ozval se jeden muž z eskorty, „prochlastal hejtman celou plukovní kasu před válkou a musel kvitovat z vojny, a teď je zas hejtmanem, a jeden felák, kterej vokrad erár vo sukno na vejložky, bylo ho přes dvacet balíků, je dneska štábsfeldvéblem, a jeden infanterista byl nedávno v Srbsku zastřelenej, poněvadž sněd najednou svou konservu, kterou měl si nechat na tři dny.“

[II.4] Brigádní telefonní centrála hlásí, že se nikam nemůže dozvonit, jenom že hlásí štáb 75. regimentu, že právě dostali od vedlejší divise rozkaz ,ausharren’, že se nemůže smluvit s naší divisí, že Srbové obsadili kótu 212, 226 a 327, žádá se o zaslání jednoho batalionu jako svaz a spojení po telefonu s naší divisí.

Literature

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 527), ,1914

- IR 75 - bojová cesta, ,2014-2023 [d]

- Překládání náhradních těles jednotek z Čech, ,2014-2023

- 75. pěší pluk,

- Padlí a ranění vojáci IR 75 v bitvě u Zborova - 1. část,

- Die Feuertaufe der 75er, Josef Daubek,1924-1928

- Přísaha c. a k. pěš pl. č. 75., ,14.8.1914

- Odjezd jindřichohradecké posádky, ,1.1.1915

- Ctěnému obyvatelstvu města Jindřichova Hradce!, ,26.11.1915 [a]

- Gott strafe England, Jaroslav Hašek,15.10.1917J [e]

- Jindř. Hradec a Slovensko v minulosti, ,18.9.1936 [c]

- Jak prožívali Pětasedmdesátníci státní převrat v Debrecíně, ,23.10.1936 [b]

- Der Oberste Kriegsherr und sein Stab, ,1908

| a | Ctěnému obyvatelstvu města Jindřichova Hradce! | 26.11.1915 | |

| b | Jak prožívali Pětasedmdesátníci státní převrat v Debrecíně | 23.10.1936 | |

| c | Jindř. Hradec a Slovensko v minulosti | 18.9.1936 | |

| d | IR 75 - bojová cesta | 2014-2023 | |

| e | Gott strafe England | Jaroslav Hašek | 15.10.1917J |

| Sport-Favorit |  | ||||

| Praha I./583, Na Příkopě 15 | ||||||

| ||||||

The club's address in 1910

,3.7.1902

,19.3.1909

Sport-Favorit is mentioned in connected with the running exploits of Oberleutnant Witinger. Years ago he had won the trophy that Feldkurat Katz borrowed to use at the field mass and at the time he was running for Sport-Favorit. Later in the chapter it is revealed that the race in question was from Vienna to Mödling.

Background

Sport-Favorit was a German sports club in Prague and officially named Fussballclub Sport-Favorit. Despite the name and the main focus on football they also did athletics and cycling, at least during the early years.

The club was founded on 1900 through a merger between Sport and Favorit[a], two clubs that had existed since 1899. The offices were located on Na Příkopě (Graben), was associated with Café Central, and the football matches were played at Letná. The running competition mentioned in the article to the right took place at a course in Bubny on 13 July 1902.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.2] Tak dostaneme sportovní pohár od nadporučíka Witingra od 75. pluku. On kdysi před lety běhal o závod a vyhrál jej za 'Sport-Favorit'. Byl to dobrý běžec. Dělal čtyřicet kilometrů Vídeň-Mödling za 1 hodinu 48 minut, jak se nám vždycky chlubí. Jsem hovado, že všechno odkládám na poslední chvíli. Proč jsem se, trouba, nepodíval do té pohovky.“

[I.10.2] Konečně se ozvalo „Zum Gebet!“, zavířilo to prachem a šedivý čtverec uniforem sklonil svá kolena před sportovním kalichem nadporučíka Witingra, který on vyhrál za Sport-Favorit v běhu Vídeň-Mödling.

Literature

- Spolkový katastr,

- Fussballclub "Sport Favorit in Prag", ,1910

- Ein fusion zwischen ..., ,7.11.1900 [a]

- Různé zprávy, ,27.11.1902

- Athletik, ,30.6.1904

- Sportovní věstník, ,18.3.1911

| a | Ein fusion zwischen ... | 7.11.1900 |

| Bruska |  | |||||

| Praha III./132, Pod Bruskou 2 | |||||||

| |||||||

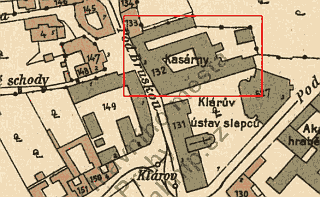

Bruska was the barracks where Hauptmann Šnábl served. Švejk was sent here by Feldkurat Katz to borrow money and to buy ořechovka (nut spirits).

Background

Bruska refers to the now demolished barracks that were located at Klárov in Malá Strana, next to Klárův ústav slepců. They were named after the small (mostly underground) stream Bruska (Brusnice) that flows past the site.

These barracks were for most of the pre-war time the home of the staff of Infanterieregiment Nr. 28, one or more battalions, the replacement district command, and K.u.K. Artillerieregiment Nr. 8. Units were frequently moved around so who occupied the barracks could change as often as each year. In 1914 only the 2nd battalion of IR28 was garrisoned here.

In 1914 the building was sold to the city of Prague and the military personnel were moved to Josefskaserne in Praha II. and Ferdinandkaserne in Karlín. The recruitment command was however still there in October, so if Hauptmann Šnábl had any base in the real world he would surely have belonged to this unit. Still it seems that the building was used by the military also later. In 1915 Landsturm drafts took place here and in 1916 Prager Tagblatt reported on Hungarian soldiers on the site. In 1919 the building was used for recruitment of army volunteers. The barracks were demolished in 1922 and the former site is now only partly occupied by buildings.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.3] Kdyby zde byla pravá ořechovka,“ povzdechl, „ta by mně spravila žaludek. Taková ořechovka, jako má pan hejtman Šnábl v Brusce.“

Literature

- S osmadvacátníky za světové války, ,1936

- Oheň v kasárnách, ,7.11.1900

- Räumung der Bruskakaserne, ,17.4.1914

- Under Blinden, ,23.9.1916

- Ze Svazu českoslovanského studentstva, ,23.6.1919

- Bývalá kasárna Pod Bruskou čp. 132/III,

- Historie c. a k. pěšího pluku č. 28,

- Podzemí potoka Brusnice,

| Vršovice kasárna |  | |||||

| Vršovice/429, Na Mičánkách - | |||||||

| |||||||

Eidesleistung vor Abmarsch des 8. Marschbaons des IR. Nr. 73 in Prag-Wrschowitz 1915.

,Maxmilian Hoen

Vršovice kasárna was a garrison where Švejk dropped by to borrow money from Oberleutnant Mahler. In [I.14] and [I.15], the plot may the most part takes place in Vršovice, without this being stated explicitly. Some indication is the fact that Blahník took the stolen dog Max here, but in the next chapter Oberleutnant Lukáš seems to live much nearer the centre.

Background

Vršovice kasárna probably refers to the barracks in Vršovice that were home of IR73 at the time. In 1914 it housed the regiment's staff and three battalions. In contrary to other Bohemian regiments they were allowed to stay in their home garrison during the whole war.

Most of the military personnel left the barracks hastily after the revolution of 28 October 1918 and set off to their home region of Eger (now Cheb). The barracks were immediately taken over by local militiamen (Sokol) and a few days later the newly formed Czechoslovak artillery moved in. The site was used by the military until the 1950's and now houses the court of four districts.

There was also another barrack in Vršovice but as it was used by Traindivision Nr. 8 and is a less likely candidate than the above-mentioned infantry barracks. The address was Palackého třída 334 (now Moskevská). This barrack compex was extenisve and contained staff buildings, stables, stores and officer's accommodation. The barracks were gradually demolished between 1965 and 1983 and the housing estate Vlasta now occupies the site.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.10.3] Jestli tam nepochodíte, tak půjdete do Vršovic, do kasáren k nadporučíkovi Mahlerovi.

Credit: Michael Kummer

Literature

- Letzte Kämpfe vor Belgrad, Maximilian Hoen,1939

- Das k.u.k. IR. 73 im 1. Weltkrieg,

- Requisitionen in Prager Kasernen, ,31.10.1918

|

I. In the rear |

| |

10. Švejk as a military servant to the field chaplain | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 3.12.2024 |