Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

7. Švejk goes in the military | |||

| K.u.k. Kriegsministerium |  | ||||

| Wien I./-, Stubenring 1 | ||||||

| ||||||

Stubenring 1, neues Kriegsministerium; Foto: A. Stauda (um 1914)

,1914

K.u.k. Kriegsministerium is mentioned by the author when he informs that the ministry remembered Švejk at the time when the Austrians where fleeing across Raba, and that Švejk was to help them out of the difficult situation.

The ministery appears again at the start of [I.13] when Feldkurat Katz receives a directive about how to adminster the last rites. In [II.1] the author notes that issued the propaganda posters that Švejk read at the station in Tábor (see Trainsoldat Bong and Zugsführer Danko).

When Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek describes Fähnrich Dauerling the ministry is mentioned twice. They allegedly published the book Drill oder Erziehung* and Marek also claims that this is where the most stupid officers end up.

* Drill oder Erziehung was published by L.W Seidel & Sohn, not by Kriegsministerium. The author was Johann Orth.

Background

K.u.k. Kriegsministerium (I. and R. Ministry of War) was the common ministery of war of Austria-Hungary, one of the three ministeries that the two constituent parts of the Dual Monarchy shared. Minister of War from 1912 until 1917 was Alexander von Krobatin. He was regarded as one of the hawks, who wanted to settle scores with Serbia at the slighest pretext. As can be seen on the picture he gave audience to civilians two hours every week.

The war ministry was not responsible for k.k. Landwehr and Honvéd, the territorial armies of the two parts of the empire. The formal status Švejk held with regards to the ministery is unclear. He was classified as Landsturm (domobranec), reservists that were only called up on in great danger to the motherland.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] V době, kdy lesy na řece Rábu v Haliči viděly utíkat přes Ráb rakouská vojska a dole v Srbsku rakouské divise jedna za druhou dostávaly přes kalhoty to, co jim dávno patřilo, vzpomnělo si rakouské ministerstvo vojenství i na Švejka, aby pomohl mocnářství z bryndy.

[I.13] Polní kurát Otto Katz seděl zadumané nad cirkulářem, který právě přinesl z kasáren. Byl to rezervát ministerstva vojenství

[I.15] Zatraceně, proč ministerstvo vojenství dává takové věci do školního programu. To je přece pro dělostřelectvo.

[II.1] Strážnice byla vyzdobena litografiemi, které v té době dalo rozesílat ministerstvo vojenství po všech kancelářích, kterými procházeli vojáci, stejně jako do škol i do kasáren.

[II.2] A seshora ho bombardovali přípisy, ve kterých ministerstvo zemské obrany poukazovalo, že z píseckého okresu podle zpráv ministerstva vojenství přecházejí k nepříteli.

[II.2] Jeho hloupost byla tak oslňující, že byla největší naděje, že snad po několika desetiletích dostane se do tereziánské vojenské akademie či do ministerstva vojenství.

[II.2] Jednoroční dobrovolník si oddechl a vypravoval dál: „Vyšla nákladem ministerstva vojenství kniha ,Drill oder Erziehung’, ze které vyčetl Dauerling, že na vojáky patří hrůza.

[II.3] Že psaní pošle na velitelství pluku, do ministerstva vojenství, uveřejní je v novinách.

Also written:I. and R. Ministry of WarenC. a k. ministerstvo vojenstvícz

Literature

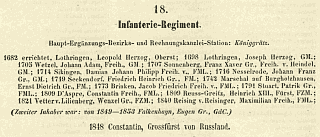

| Infanterieregiment Nr. 18 |  | ||||

| Hradec Králové/-, - - | ||||||

| ||||||

,1908

, 1859

Infanterieregiment Nr. 18 is mentioned in the song Jenerál Windischgrätz a vojenští páni through the term "the eighteenth band". See Solferino and Piedmont.

Background

Infanterieregiment Nr. 18 was an infantry regiment with recruitment district Hradec Králové that took part in nearly every war the Habsburg Empire fought ever since the regiment was founded in 1682.

The theme of the song is the battle of Solferino that decided the outcome of the Second Italian war of independence in 1859. During the battle only the regiment's 4th battalion was involved, the other battalions were fortunate enough to be assigned border duty.

In 1914 the bulk of the regiment's soldiers were Czechs (75 per cent), the rest Germans.

An alternative version

Václav Pletka claims that the "18th gang" refers to a Feldjägerbataillon from Prague that was dissolved in 1893[a]. This seems however unlikely as none of the 29 Jäger-Bataillone where in 1859 garrisoned in Prague. Feldjägerbataillon Nr. 18 was located in Krumau but it remains to be investigated whether it participated by Solferino.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

Some verses of the song about General Windischgrätz are also quoted in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí and in a context that is very similar.[1]

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Krve po kolena a na fůry masa, vždyť se tam seka vosumnáctá chasa, hop, hop, hop!

Literature

- Písničky Josefa Švejka, ,1968 [a]

- 1859 - C.k. řadový pěší pluk č.18 v bitvě u Solferina, ,z.s.

- Militärschematismus des Österreichischen Kaisertums, ,1859

- Der Oberste Kriegsherr und sein Stab, ,1908

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| a | Písničky Josefa Švejka | 1968 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

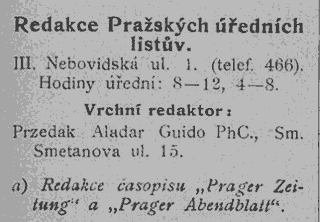

| Pražské úřední noviny |  | ||||

| Praha III./387, Karmelitská ul. 6 | ||||||

| ||||||

, 1907

,30.11.1914

,5.7.1914

,8.9.1914

Pražské úřední noviny prints a glowing homage to the patriotic cripple Švejk after he was pushed to the draft commission in a wheelchair. The title was: "Patriotism of a cripple".

Background

Pražské úřední noviny (Prague Official Newspaper) is not listed in the newspaper section of the address books of 1907 and 1910, but there is little doubt that the author refers to the publications of c.k. Místodržitelství (k.k. Statthalterei), often referred to by this or similar names like Pražské úřední listy, in German Prager Amtsblätter. These newspapers were mouthpieces of the Austrian authorities in Bohemia, headed by the Statthalter (governor).

The newspapers were published in Czech and German, with one official and one regular commercial part. The main periodical was Prager Zeitung in German, in Czech Pražské Noviny. Both were morning papers that were published every day except Monday. In the afternoon of working days they also published Prager Abendblatt, albeit in German only. Official announcements were printed in a separate add-on on weekdays: Úřední list Pražských Novin and Amtsblatt der Prager Zeitung respectively. On Sundays an entertainment magazine was added.

The editorial offices were located in Malá Strana, right behind Kampa island[a]. Some time between 1907 and 1910 they changed address, but were still in the same block. Editor in chief for all the papers was Aladar Guido Przedak, for the Czech part Jan Svátek. Przedak (1857-1926) was the chief editor from 1900 until 1918 and also bore the title k.u.k. Regierungsrat. The circulation of Prager Abendblatt was quintupled during his reign as editor[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] O celé této události objevil se v „Pražských úředních novinách“ tento článek:

[I.7] Vlastenectví mrzáka. Včera dopoledne byli chodci na hlavních pražských třídách svědky scény, která krásně mluví o tom, že v této veliké a vážné době i synové našeho národa mohou dáti nejskvělejší příklady věrnosti a oddanosti k trůnu stařičkého mocnáře. Zdá se nám, že se vrátily doby starých Řeků a Římanů, kdy Mucius Scaevola dal se odvésti do boje, nedbaje své upálené ruky. Nejsvětější city a zájmy byly včera krásně demonstrovány mrzákem o berlích, kterého stará matička vezla na vozíku pro nemocné. Tento syn českého národa dobrovolně, nedbaje své neduživosti, dal se odvésti na vojnu, aby dal svůj život i statky za svého císaře. A jestli jeho volání „Na Bělehrad!“ mělo tak živý ohlas v pražských ulicích, jest to jen svědectvím, že Pražané skýtají vzorné příklady lásky k vlasti a k panovnickému domu.

[I.8] Zatímco jsem seděl, děly se v kasárnách divy. Náš obršt zakázal vojákům vůbec číst, třebas by to byly ,Pražské úřední noviny’, v kantině nesměli balit do novin ani párky, ani syrečky. Vod tý doby vojáci začli číst a náš regiment byl nejvzdělanější.

Also written:Prague Official NewspaperenPrager AmtszeitungdePraha Amtstidendeno

Literature

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1910 [a]

- Przedak (Předak), Aladar Guido (1857-1926), Journalist und Fachschriftsteller, [b]

- Prager Abendblatt, ,1914

| a | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1910 | |

| b | Przedak (Předak), Aladar Guido (1857-1926), Journalist und Fachschriftsteller |

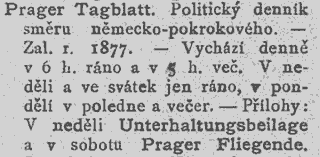

| Prager Tagblatt |  | ||||

| Praha I./896, Panská ul. 12 | ||||||

| ||||||

,1.12.1914

Listed in the 1910 address book.

,5.1.1923

,17.1.1926

Prager Tagblatt briefly notes that Švejk was protected by Germans against Czech agents from the Entente who wanted to lynch him on his way to Střelecký ostrov.

The newspapers features again in connection with the theft of Fox. The dog's owner, Oberst Kraus, placed adverts both here and in Bohemia where he promises a reward of 100 crowns.

Background

Prager Tagblatt was a German language daily published in Prague from 1877 until 1939. The paper had a reputation for outstanding journalistic qualities, and was regarded as one of the very best German-language newspapers of its time. It was over the years associated with a number of distinguished writers, amongst them Max Brod, Egon Erwin Kisch, Josef Roth, Michal Mareš and Friedrich Torberg. Franz Kafka was also amongst those who contributed to the newspaper and he was also an avid reader of it.

During World War I the paper aligned with the propaganda, but was often the victim of censorship, and put more emphasis on the human costs of the war than many other papers. In the inter-war years the daily re-established its reputation for journalistic excellence, but hardly two months after the German invasion in March 1939 it was closed for good. The numerous Jewish staff had been dismissed already during the days after the invasion.

Politically it was regarded as liberal-democratic, and in Czech address books it is listed as "German progressive". Chief editor in 1910 was Gustav Horn. The editorial and administration offices were located in Panská ulice (Herrengasse)[c], incidentally very close to where Oberst Kraus caught Oberleutnant Lukáš red-handed with the stolen Fox.

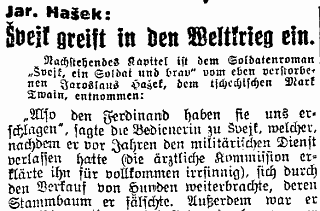

Prager Tagblatt and Hašek

After Jaroslav Hašek's death on 3 January 1923 Prager Tagblatt played a major role in acknowledging and spreading the word about the late author and his satirical masterpiece. This was largely thanks to Max Brod, a writer and journalist who is better known as the custodian of Franz Kafka's literary heritage.

Already on 5 January the paper printed an obituary[a], and Brod's own translation of the first chapter of The Good Soldier Švejk appeared in the same issue[b]. During the next fifteen years Švejk and Hašek showed up repeatedly in the newspaper's columns, particularly in 1926 when the full translation into German by Grete Reiner was published. At least seven of Hašek's short stories (translated into German) were printed in Prager Tagblatt in the years after the author's death.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí Prager Tagblatt is also mentioned but in a differnt setting. In Švejk's cell at c.k. policejní ředitelství was sitting a higher official from the governor's office who had been arrested in front of their editorial offices in Panská ulice.[1]

Velmi zamyšleně se tvářil pán v prostředních letech, velmi slušně oděný, který se včera dostal do chumlu před Prager Tagblattem v Panské ulici. Někdo ho zatkl, radu od místodržitelství, omdlel jim rozčilením, dopravili ho na policejní ředitelství v truhle a pak našli u něho v kapse nějaké kamení. Ještě ho nevyslechli. Domnívají se, že chtěl vytlouci Prager Tagblatt, on, místodržitelský rada, který nečte kromě úředního deníčku jiných novin než Prager Tagblatt, za manželku má Němkyni a …

Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein (Max Brod)

"Also den Ferdinand haben die uns erschlagen", sagte die Bedienerin zu Švejk, welcher, nachdem er vor Jahren den militärischen Dienst verlassen hatte (die ärtztliche Kommission erklärte ihn für vollkommen irrsinnig), sich durch den Verkauf von Hunden weiterbrachte, deren Stammbaum er fälschte.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Ve stejném smyslu psal i „Prager Tagblatt“, který končil svůj článek slovy, že mrzáka dobrovolce vyprovázel zástup Němců, kteří ho svými těly chránili před lynchováním ze strany českých agentů známé Dohody.

[I.15] „Pane nadporučíku,“ pokračoval plukovník, „považujete za správné jezdit na ukradeném koni? Nečetl jste inserát v ,Bohemii’ a v ,Tagblattu’, že se mně ztratil stájový pinč?

[I.15] V tiché resignaci seděl nadporučík na židli a měl takový pocit, že nemá tolik síly nejen dát Švejkovi pohlavek, ale dokonce ukroutit si cigaretu, a sám nevěděl ani, proč posílá Švejka pro „Bohemii“ a „Tagblatt“, aby si Švejk přečetl plukovníkův inserát o ukradeném psu.

Literature

- Jaroslav Hašek, ,5.1.1923 [a]

- Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein, ,5.1.1923 [b]

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1910 [c]

- Theater Adrie, ,25.12.1921

- Der brave Soldat Švejk ist dem Ministerium zu schlimm..., ,22.2.1925

- Ein Blick ins Atelier, ,29.1.1926

- Der brave Soldat Schwejk im Weltkrieg, ,8.5.1926

- Hašek in deustcher Sprache, ,4.9.1926

- Der gute Soldat Švejk vor Gericht, ,6.3.1924

- Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Hašek, ,23.12.1926

- Mužné zakročení pana Silberbergra proti Tagblattu, Jaroslav Hašek,11.12.1908

- Smutný konec válečného zpravodaje Prager Tagblattu, Eduard Drobílek,25.11.1912

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| a | Jaroslav Hašek | 5.1.1923 | |

| b | Švejk greift in den Weltkrieg ein | 5.1.1923 | |

| c | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1910 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Bohemia |  | ||||

| Praha I./211, Liliova ul. 13 | ||||||

| ||||||

The first issue after the change of names

,15.11.1914

Ferdinand Mestek de Podskal, E.E. Kisch

,5.7.1914

Bohemia published an article that resembled the one from Prager Tagblatt about the cripple Švejk and his journey in a wheelchair. It adds that gifts for the benefit of the soldier can be presented at the administrative office. In the next chapter it becomes clear that it was in this paper Baronesse von Botzenheim read about the keen soldier.

In [I.14] the newspaper is mentioned again as Oberst Kraus placed an advert about the missing dog and offered a reward of 100 crowns.

On the train to Tábor [II.1] it is revealed that even Oberleutnant Lukáš reads Bohemia.

Background

Bohemia was a German-language daily published in Prague from 1828 til 1938, associated with the German Liberal Party. During the war they took a strongly patriotic stance, and from 15 November 1914 even changed the name to Deutsche Zeitung Bohemia. The editorial and administration offices were located in Liliova ulice in Staré město and chief editor in 1914 was Andreas Haase. He held the position for an impressive 40 years, from 1879 to 1919.

E.E. Kisch

Their best known reporter was without doubt the legendary Egon Erwin Kisch. He worked for the paper from 1906 to 1913, and published many reports from Prague, mainly focused on the shady underworld. Kisch dedicated a feuilleton to flea circus director Mestek, mentions murderer Valeš and negro Kristian, and wrote about a number of watering holes that are familiar to readers of The Good Soldier Švejk: Apollo, Tunel, U Kocanů, Montmartre, U Brejšky a.o.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] „Bohemie“ uveřejnila tuto zprávu žádajíc, aby mrzák vlastenec byl odměněn, a oznámila, že pro neznámého přijímá od německých občanů dárky v administraci listu.

[I.15] „Pane nadporučíku,“ pokračoval plukovník, „považujete za správné jezdit na ukradeném koni? Nečetl jste inserát v ,Bohemii’ a v ,Tagblattu’, že se mně ztratil stájový pinč?

[I.15] V tiché resignaci seděl nadporučík na židli a měl takový pocit, že nemá tolik síly nejen dát Švejkovi pohlavek, ale dokonce ukroutit si cigaretu, a sám nevěděl ani, proč posílá Švejka pro „Bohemii“ a „Tagblatt“, aby si Švejk přečetl plukovníkův inserát o ukradeném psu.

[II.1] Nadporučíkovi bezděčně zacvakaly zuby, vzdychl si, vytáhl z pláště „Bohemii“ a četl zprávy o velkých vítězstvích, o činnosti německé ponorky „E“ na Středozemním moři...

Literature

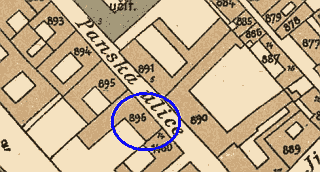

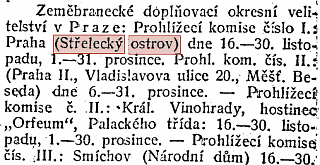

| Odvodní komise |  | |||||

| Praha I./336, Střelecký ostrov - | |||||||

| |||||||

The draft commission on 31 December 1914

Oveview of Landsturm medical examination commissions in Prague

,8.11.1914

Odvodní komise is the Czech name for Draft commission, the body that examined Švejk at Střelecký ostrov. Head of the commission was the infamous Doctor Bautze.

Background

Odvodní komise (Draft commission) refers in this context to Landsturmmusterungskommision No. 1, a temporary body who were tasked with carrying out medical examinations of Landsturm recruits who in peace time had either been declared unfit for armed service (waffenunfähig) or had been dismissed from the armed forces after initially having started their military service (superarbitriert).

Commission no. 1 was responsible for recruits who lived in Prague and had Heimatrecht in the city. In addition it examined residents of Prague with right of domicile elsewhere, if these were born from 1878 to 1883. Jaroslav Hašek belonged to the latter group (right of domicile Mydlovary, born 1883) and necessarily also Švejk. As a soldier in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 his right of domicile must have been in Heeresergänzungsbezirk Nr. 91. See Ergänzungskommando.

The commission started the examinations on 1 October 1914 when those born from 1892 to 1894 were called in. Amongst this group more than half were deemed fit for service. From 16 November to 31 December it was the turn of those born from 1878 to 1890. Amongst this group far fewer were passed capable Tauglich, less than one third. This latter group is the most interesting for us as it was here Jaroslav Hašek fit in. Everything indicates that also Švejk belonged to this group and was thus born between 1878 and 1883. On 20 January 1915 it was announced that Austrian citizen who were passed fir for duty had to report at their Ergänzungskommando on 15 February.

The examinations took place in the garden restaurant at Střelecký ostrov, on the southern part of the island. The restaurant was in 1914 a popular destination.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Když Švejk revírnímu inspektorovi ukázal, že to má černé na bílém, že dne musí před odvodní komisi, byl revírní inspektor trochu zklamán; kvůli zamezení výtržnosti dal doprovázet vozík se Švejkem dvěma jízdními strážníky na Střelecký ostrov.

Also written:Draft commissionenMusterungskommisiondeMønstringskommisjonenno

Literature

- Svolávací vyhláška E, ,22.10.1914

- Prodlídka domobranců, ,9.11.1914

- Svolávací vyhláška, ,20.1.1915

- Einberufung aller gemusterten Landsturmklassen, ,20.1.1915

- Einberufung der Landsturmjahrgange 1878-1886, ,22.1.1915

- Anekdota o Jaroslavu Haškovi, ,5.12.1918

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021

|

I. In the rear |

| |

7. Švejk goes in the military | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |