Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

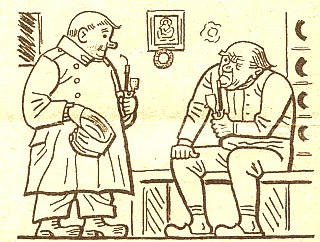

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people/animals that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2008) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others.

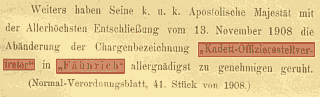

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are given in tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

II. At the front |

| |

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis | |||

| Xenophon |  | |||

| *430 BC Athen - †355 BC ? | |||||

| |||||

, 1900

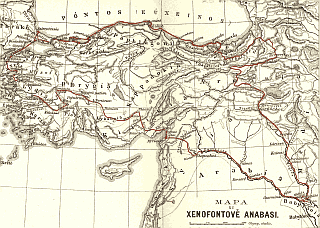

Xenophon is mentioned by the narrator when he introduces the reader to the term "anabasis". Xenophon exemplified the anabasis by travelling around "God knows where" without a map. Hašek uses this symbolism in the chapter header Švejkova budějovická anabase and also in the short follow-up where he explains what the word anabasis means.

Background

Xenophon was a Greek commander, author and historian, known for his historical descriptions of ancient Greece, his writings on Socrates, and the first eyewitness account of a battle in ancient times. His best-known book is "Anabasis". It describes the Greek mercenaries' treacherous journey home through Asia Minor after a failed military mission against Persia. It is a seven-volume work and is considered Xenophon's best. It was translated into Czech already in 1853 and by the turn of the century, it had become part of Greek language teaching at Czech middle schools (gymnasium).

Anabasis: A dig at the Legions?

Břetislav Hůla was probably the first who in writing suggested that Hašek used "anabasis" as subtle kick at the Czechoslovak Legions (1951). His conclusion was in 1953 made public in a collection of explanations that were part of a new edition of Švejk.

© LA-PNP

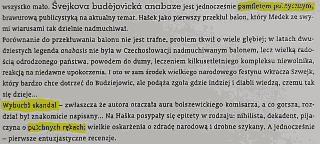

Jaroslav Hašek's symbolic use of the term anabasis has over the years led to assumptions about the author's intentions when he wrote the chapter about Švejk's anabasis. Some scholars have proposed (and even assumed) that Švejk's anabasis was intended as an ironic reference to the so-called Siberian anabasis of the Czechoslovak Legions.

In his explanations to a 1953 edition of The Good Soldier Švejk, Zdena Ančík assesses the connection as "obvious" and more was to follow, albeit decades later. Literary scholars Antonín Měšťan (1983)[a], Antoni Kroh (Polish translator of The Good Soldier Švejk) (2002) and Abigail Weil (2019)[b] all state that Hašek's use of the term "anabase" was a dig at the Legions and that the author had their so-called Siberian anabasis from Kiev to Vladivostok in mind when he penned this chapter. Until 2020 a summary of Kroh's interpretation was even found in the explanatory notes of Zenny Sadlon's translation of The Good Soldier Švejk (the most recent one).

Obviously, the hypothesis can't be dismissed outright as we cannot know what went through Hašek's mind when he wrote these lines. Speaking for the hypothesis is that irony was one of Hašek's main tools and that he had ample reasons to ridicule his former co-fighthers, some of whom had written nasty columns about him. On the other hand, we have never seen any evidence that could underpin the assumptions about Hašek's intentions with Švejk's "anabasis". One would at least expect quotes from the author himself or from people who were in contact with him at the time of writing (1921 onwards), but no such source has been identified. Alternatively, one would expect evidence that the reading public at the time perceived Švejk's anabasis as a dig at the Legions. None of this seems to be the case. Therefore, the following paragraphs shall try to analyse the origin and development of the claim and the only serious attempt to underpin it (by Kroh).

Fiala

This otherwise excellent book contains far-fecthed claims regarding Hašek and his use of the term "anabasis".

In 2004 professor Jiří Fiala (Olomouc) published a thorough analysis of "anabasis" and other motifs from The Good Soldier Švejk [e]. He reveals that Zdena Ančík in explanatory notes in the 1953 edition of the book concludes that anabasis "obviously is an ironic reference to the Legions and their fight against the Red Army, by nationalistic novel writers who coined the term Siberian anabasis"[1]. Fiala compares this to later explanations from Radko Pytlík [2] and Milan Hodík [3] and observes that neither of the latter two draws similar conclusions. Fiala in the end leaves the question open. He then proceeds by reproducing an excerpt from the book O Szwejku i o nas by Kroh[4], from a chapter titled "Two Generals".

Kroh

, s.45

© Antoni Kroh

Kroh's text, as translated by Fiala, is the starting point for the following analysis. He juxtaposes Rudolf Medek and Jaroslav Hašek in the context of the anabasis but even the title Two Generals gives ground for scepticism. Medek eventually advanced to general (1931), but associating this rank with Hašek is downright absurd.

Even more questionable is the conclusion that Kroh draws. The reader is left with the impression that the hostility that Hašek encountered in Czechoslovakia after his return from Russia in 1920 was caused by his publishing of the "anabasis" chapter in The Good Soldier Švejk, and that this triggered an avalanche of criticism, insults and harassment. Rudolf Medek lashing out at Hašek, two years before the anabasis chapter in Švejk. ,6.4.1918

There is no denying that Hašek was subjected to nasty attacks and insults, but the worst of these came to the fore when he was still in Russia and more than a year before he penned Švejk's anabasis. In an article published shortly after Jaroslav Hašek left the Legions, Medek delivered a cruel character assassination[c], and worse was to come. In early 1919 Jaroslav Colman-Cassius wrote an obituary titled Zrádce (Traitor)[d], obviously because he thought Hašek was dead. Cassius was every bit as unforgiving as Medek: writing about "small chubby hands", a clown and a drunkard, a man without spine and character.

Extracts from Cassius' nasty "obituary". Hašek read it in Irkutsk in 1920 and was deeply hurt. ,19.1.1919

When Kroh attempts to link Czech society's hostility to Hašek to the anabasis chapter he uses the phrase drunkard with chubby hands as one of the examples. The term was indeed used but pre-dated The Good Soldier Švejk. It was coined in 1920 in Irkutsk by Hašek himself, provoked by the mentioned "obituary" that he somehow got his hand on while still in Russia[5]. His response was the story Dušička Jaroslava Haška vypravuje (The little soul of Jaroslav Hašek tells) and here this insulting phrase appears. The story was printed immediately after Hašek returned to Praha[f], but many months before he wrote the "Anabasis" chapter in The Good Soldier Švejk (autumn 1921).

The links that Kroh draws to Rudolf Medek and his "Anabase" novels (5 in total) are timing-wise equally irrelevant: except for the first they were published after Hašek's death[6]. As we have seen, Medek attacked Hašek sharply at times, but this happened in 1918 and thus can't be linked to publishing the "anabasis" chapter 3 years later. According to Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj, the two met in Prague in 1921 and after a first heated encounter, they were reconciled. Kroh's attempt to establish a connection between the spiteful attacks on Jaroslav Hašek and the publishing of the chapter Švejkova budějovicka anabase collapses when subjected to a timeline analysis.

Weil

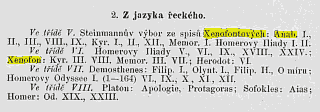

Výbor ze spisů Xenofontových, , Kyrupaideie

A novelty appeared at Harvard University in 2019 through a dissertation thesis on Hašek by Abigail Weil[b]. Here the motif anabasis and Hašek's alleged dig at the Legions is given ample space. Whereas Kroh at last seeks to explain (albeit unconvincingly) the connection to the Legion's anabasis Weil takes it for granted that there is a connection. Nor does she make any reference to Antonín Měšťan, Kroh's book (or Fiala's discussion of it) so we must assume that she was unaware of these papers at the time of writing.

Perhaps this belief is inspired or underpinned by Zdena Ančík (read Břetislav Hůla) and his comment in the Švejk edition from 1953 (Weil explicitly refers to it as "the standard edition").

As one would expect from a literary scholar her thesis is strong on historical context, literary context and analysis but marred by a number of factual errors and inaccuracies. Many of the mistakes are admittedly "inherited" from Radko Pytlík and even more so from Cecil Parrott.

Ančík

So what about Břetislav Hůla's explanation from 1951, published by Zdena Ančík in 1953 (17th edition, Státní nakladatelství)? It was written at a time when anything that could put the pre-war "bourgeoise" republic and the Legions in a bad light was the order of the day. It is also striking that by 1955 (22nd edition, Práce), the same Ančík had removed the reference to the Legions and their anabasis. Nor does a completely different set of notes by Milan Jakovič (26th edition, Odeon, 1968) contain any such allusions to "anabase and the Legions".

Hašek and Xenofon

Xenofon was on the curriculum when Hašek was a pupil at the gymnasium.

The term "anabase" was by no means unknown in Czech literature even before the deluge of legionnaire novels inundated Czechoslovakia in the twenties. One of the teachers at the gymnasium in Žitná ulice, where Hašek studied from 1893 to 1898, was the famous author Alois Jirásek. He was teaching geography and history and already in 1886 he wrote a book with the theme anabasis. Xenophon's own magnum opus had been translated into Czech even earlier. Classical Greek was one of the subjects at the gymnasium and Xenofon was on the curriculum. That said the subject was introduced from the 5th form, a step Hašek never reached as he was forced to leave in the 4th. Jirásek didn't teach the classes of young Jaroslav (Ia, IIa, IIIa and IVa), despite Václav Menger a.o. claiming the opposite[7]. Still, the fact that Xenofon was in the curriculum shows that he must have been well known amongst educated Czechs. It should be added that Greek was taught from the 3rd form so Xenophon's name may have been introduced already at this stage.

Xenofon and his anabasis was a known theme for Hašek five years before he wrote Švejk. Čechoslovan,25.9.1916

Even though Hašek probably didn't study Xenophon as a subject at school there is no doubt that he had a good general knowledge of and interest in the history of ancient Greece. This is obvious already in the introduction to the novel. But even more importantly: it is easy to prove that Jaroslav Hašek's awareness of Xenophon was unrelated to the anabasis of the Legions. In Dopis z fronty (Letter from the front)[h] both Xenophon and his anabasis are mentioned. At this time it could never have been a question of making fun of a Siberian anabasis that was to take place two years into the future. None of the mentioned scholars seem to have registered that Hašek used the theme "anabasis" already in 1916. Even three years earlier Hašek had mentioned Xenophon (but not the anabasis) in one of his stories[g].

Conclusion

Hašek's pre-war story in Svět and the mentioned Letter from the front are of course no proof that he later didn't poke fun at the Legions, but it does indicate that he could easily have written about Xenophon and his anabasis without any such intent.

We have in vain searched digitised newspapers from 1921 or 1922 for any sign that any writers or critics connected Švejk's anabasis with the Legions. Even extending the search to 1950 and including the extensive inter-war legionnaire literature has proved futile. There must also be a reason why explanations to Švejk published from 1955 onwards don't connect the Legions and Švejk's anabasis anymore. The answer is probably that the communist publishers no longer believed in the hypothesis (perhaps they had by now discovered "Letters from the front" from 1916?). If there had been any substance in the theory they surely would have used Švejkova budějovická anabase for what it was worth.

Sergey Soloukh's notes

1. The term itself "anabasis" for any long and hard journey of armed man was quite standard for the epoch. For example it was widely used in Russian literature about Great and Civil wars (generals Denikin and Krasnov, writer and lit.critic Shklovsky). And all of them without any connection to Cz.Legion. So it was very standard in war-torn Russia of the time and not specifically used for particular Legion affair. And quite vice-versa, was rather used by Cz.Legion as a standard for "the journey of armed men" then something born and particularly and uniquely attributed to Legion move.

2. If it would be interpreted as an insult to Cz,Legion or an attempted joke on it at the moment of appearance of this chapter it definitely would be noted as such and discussed in Cz.press of epoch. But we know it didn't. It means and confirms my p.1. the term "anabasis" at that time was not considered specific and unique for depiction of Cz.Legion adventure only, it was freely used standard term for any "journey of the armed men". And only 30 years later it was interpreted as unique and specific to Legion adventure for the goals of communist propaganda.

Dva generálové (extr.). Antoni Kroh, transl. Jiří Fiala

Slovo „anabáze" mělo tehdy v češtině jediný, a to samozřejmý význam: znamenalo prodírání se česko- slovenských legií z Ukrajiny přes Sibiř do Vladivostoku. Kapesní slovník cizích slov (vydaný v Praze roku 1971) již objasňuje toto slovo subtilním a diskrétním způsobem: „Anabáze — probíjení se velkých vojenských oddílů do vlasti." Legenda „anabáze", zvláště živá ve dvacátých letech, byla živena a pěstována po celé období meziválečného Československa. Rudolf Medek je současně jeden z jejích tvůrců i její i hrdina. A nyní si připomeňme kapitolu Švejkova budějovická anabáze (II, 2). Švejk jel spolu s nadporučíkem Lukášem vlakem z Prahy do Budějovic. Po incidentu se záchrannou brzdou byl vysazen v Táboře a uvězněn. Když se ukázalo, že nemá peníze ani dokumenty, podporučík sloužící na nádraží mu přikázal, aby šel do Budějovic pěšky. „A čert ví, jak se to stalo, že dobrý voják Švejk místo na jih k Budějovicím šel pořád" rovně na západ. Není známo, jak se to stalo, ale je známo, že se to stalo nevědomky, poněvadž Švejk byl přece na západ." Není známo, jak se to stalo, ale je známo, že se to stalo nevědomky, poněvadž Švejk byl přece dobrý voják, žádný dezertér; on vskutku chtěl dorazit do Budějovic! Proč tam tedy nešel přímo, jen pořád kroužil a kroužil dokola? Protože byl idiot? Mnoho polských milovníků Švejka, jichž jsem se dotazoval, to právě tak vysvětluje. Ale kapitole Švejkova budějovická anabáze je možné porozumět teprve tehdy, když si uvědomíme, kdy a za jakých okolností byla napsána. Je to jedna z nejskvostnějších pasáží románu. Jako každé velké umělecké dílo se vymyká jednoznačným výkladům. Můžeme ji označit za panorama českého venkova, zvěčněním lidových typů a tehdejších nálad. Je to rovněž radostný hymnus ke cti životu, nespoutaný smích jakoby z Rabelaise. Rovněž groteska. Lze tam najít reminiscence na autorova dobrodružství. Ale to vše je málo. Švejkova budějovická anabáze je současně politický pamflet, bravurní publicistika na aktuální téma. Hašek jako první propíchl balon, který Medek se svými věrnými tak zdatně nafukoval. Přirovnání k balonu není trefné, problém vězel mnohem hlouběji; ve dvacátých letech nebyla legenda „anabáze" nafukovaným balonem, ale velikou radostí znovuzrozeného státu, důvodem hrdosti, léčbou několikasetletého komplexu zotročence, reakcí na nedávná pokořování. A tu do samého středu národní slavnosti vchází Švejk, který velice touží dorazit do Budějovic, ale dostává se kamsi úpině jinam a čert ví, proč se tak děje... Vybuchl skandál — zvlášť když autora obklopovala aura bolševického komisaře, a co horšího, kapitola byla znamenitě napsána... Na Haška se sesypaly přívlastky jako nihilista, dekadent, pijan s opuchlýma rukama; velké obžaloby ze zrady národa i drobné šikany. A současně — první entuziastické recenze.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Starověký válečník Xenofon prošel celou Malou Asii a byl bůhvíkde bez mapy. Staří Gotové dělali své výpravy také bez topografické znalosti. Mašírovat pořád kupředu, tomu se říká anabase. Prodírat se neznámými krajinami. Být obklíčeným nepřáteli, kteří číhají na nejbližší příležitost, aby ti zakroutili krk.

Sources: Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Hašek, Jiří Fiala, Antoni Kroh, Abigail Weil, Ferdinand Hoffmeister, Sergey Soloukh

Also written:XenofónczXenophonde

| 1. | Even though Zdena Ančík is credited with authorship of the explanations they were almost entirely the work of Břetislav Hůla. He passed his typewritten notes on to Ančík in 1951 and the latter only did some minor editing before publishing them in 1953, and again in 1955, now slightly amended. |

| 2. | Radko Radko Pytlík, Kniha o Švejkovi, 1982. |

| 3. | Milan Hodík, Encyklopedie pro milovníky Švejka, 1998. |

| 4. | Antoni Kroh, O Szwejku i o nas, 2002. |

| 5. | The story was first printed in Večerní Právo lidu 31 December 1920 but was dated 25 August so it must have been written in Irkutsk. This means that Hašek must have read his own obituary already there. It was also the first story Hašek had printed after his return to Prague. |

| 6. | Rudolf Medek, Anabase, 1927. |

| 7. | Jaroslav Hašek had to repeat the 4th year and finally left the gymnasium in February 1898. This school year Jirásek actually taught class IVa so Václav Menger may still be correct. |

Literature

- Výbor ze spisů Xenofontových, Anabase, Kyrupaideie1910

- V cizích službách1886

- Proč dostal profesor Fridrich Nobelovu cenu míruJaroslav Hašek26.4.1912

- Okrašlovací spolekJaroslav Hašek12.5.1922

| a | Realien und Pseudorealien in Hašeks "Švejk" | 1983 | |

| b | Man Is Indestructible: Legend and Legitimacy in the Worlds of Jaroslav Hašek | 2019 | |

| c | Průkopníci | Rudolf Medek | 6.4.1918 |

| d | Zrádce | 19.1.1919 | |

| e | Několik editologických poznámek k románu Jaroslava Haška Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války | 2004 | |

| f | Dušička Jaroslava Haška vypravuje | Jaroslav Hašek | 31.12.1920 |

| g | O dobrodružných výpravách | Jaroslav Hašek | 23.6.1913 |

| h | Dopis z fronty | Jaroslav Hašek | 25.9.1916 |

| Caesar, Julius |  | |||

| *13.7.100 BC ? Roma - †15.3.44 BC Roma | |||||

| |||||

, 1892

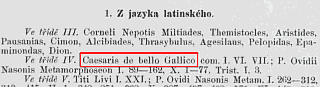

Curriculum, gymnasium Žitná ulice, 1896

"Jednoročáci", , 1931

Caesar is mentioned by the author when he introduces the reader to the term "anabasis". Caesar's legions marched all the way to the Gallic Sea without maps.

In [II.2], in the cell in Budějovice, Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek invokes the name of Caesar through the saying: Morituri te salutant, Caesar!" (The dead salute you ...)

Background

Caesar was a Roman commander, politician and author. He had become most potent citizen of Roman Empire when he was murdered by senator Brutus in 44 BC. At that time he held the title "dictator in perpeteo". During his reign he undertook extensive reforms, centralising the administration. The area of the empire was greatly extended, including Britannia.

The Gallic Sea

In The Good Soldier Švejk the source of the information about the legions and Gallic Sea seems to be Caesar's own book De Bello Gallico (The Gallic Wars)[a]. It is also worth noticing that this work was on the Latin curriculum in the 4th year at the gymnasium that Hašek attended[b].

Morituri te salutant

The saying "morituri te salutant" is of unknown origon and is hardly known in Roman history writing. One theory is that it was used by gladiators before they entered the fight. Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek's interpretation is that it refers to Emperors in general and not the person Caesar and this is the most widespread assumption. There are several variations, amongst them Ave, Imperator, morituri te salutant and Ave, Caesar, morituri te salutant. On the other hand Marek struggles with conjugation og Latin verbs. The term means "those about to die salute you", not "the dead salute you".

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Tam někde na severu u Galského moře, kam až se také dostaly římské legie Caesarovy bez mapy, řekly si jednou, že se zas vrátí a pomašírujou jinou cestou, aby ještě víc toho užily, do Říma. A dostaly se tam také. Od té doby se říká patrně, že všechny cesty vedou do Říma.

[II.2] Morituri te salutant, Caesar! Mrtví tě pozdravují, císaři, ale profous je pacholek.

Also written:Julius CaesarczJulius CäsardeGaius Iulius Caesarla

| a | Clas Merdin: Tales from the Enchanted Island | ||

| b | Devátá výroční zpráva cís. král. vyššího gymnasia v Žitné ulici v Praze | 1896 |

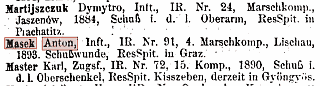

| Mašků, Antonín |  | ||||

| ||||||

, 20.4.1915

Toníček Mašků had ran away from the call-up to k.k. Landwehr in Plzeň but was caught soon after. He was the husband of a niece of the old lady who helped Švejk by Vráž. The latest news was that he had lost a leg at the front.

Background

Toníček Mašků doesn't appear to have any real life model. One track may be information from the old grandmother in Vráž that he was called up to join k.k. Landwehr in Plzeň and that he had lost a leg. The first indicates that he served with k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7. Had he lost a leg he would also figure in a Verlustliste but didn't. Additionally one would expect a recruit with Heimatrecht Vráž to serve in Písek's k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 28 and not in Plzeň.

Mašků is not an official surname but searches in the casualty list for the similar Antonín Mašek give hits, albeit none with k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7. Interestingly there was one in IR. 91 but connecting him to the k.k. Landwehr soldier from Vráž is far fetched.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „U nás byl taky jeden takovej nezbeda. Ten měl ject do Plzně k landvér, nějakej Toníček Mašků,“ povzdechla si babička, „von je vod mojí neteře příbuznej, a vodjel. A za tejden už ho hledali četníci, že nepřijel ku svýmu regimentu. A ještě za tejden se vobjevil u nás v civilu, že prej je puštěnej domů na urláb. Tak šel starosta na četnictvo, a voni ho z toho urlábu vyzdvihli. Už psal z fronty, že je raněnej, že má nohu pryč.“

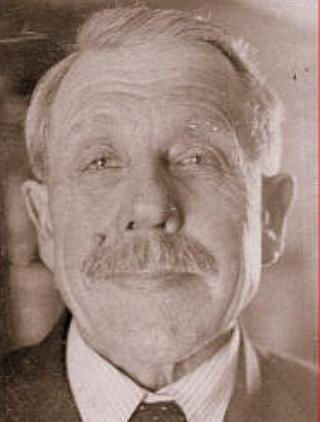

| Pantát Melichárek |  | ||||

| ||||||

,17.2.1924

,6.1936

Václav Melichar

© Ivana Sibková

Melichárek was a farmer and brother of the old woman from Vráž. He lived in Radomyšl in Dolejší ulice behind Floriánek. He was very suspicious of Švejk who he assumed had deserted and wanted nothing to do with him.

Background

is supposed to have been inspired by Václav Melichar who lived in Dolejší ulice, just as the author writes. According to his descendants, Hašek visited Radomyšl in 1915 and Melichár's wife is said to have made him "bramborovka". The story featured in televizion programmes both in 1983 and 2002[a].

The mystery is how the author got this far from Budějovice without being noticed (60 km). Although several witnesses reveal that Hašek went on detours during his time in IR. 91, none of them confirmed that he got as far as Radomyšl.

Melichar

Václav Melichar was born in 1878 so he would have been 36 when Hašek allegedly visited. This rules out that he could have been the brother of any old grandmother from Vráž as described in The Good Soldier Švejk. He and wis wife Anna bought the cottage Chalupa Mlčonavská at Radomyšl No. 15 in 1912.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] V Radomyšli Švejk našel k večeru na Dolejší ulici za Floriánkem pantátu Melichárka. Když vyřídil mu pozdrav od jeho sestry ze Vráže, nijak to na pantátu neúčinkovalo. Chtěl neustále na Švejkovi papíry. Byl to nějaký předpojatý člověk, poněvadž mluvil neustále něco o raubířích, syčácích a zlodějích, kterých se síla potlouká po celém píseckém kraji.

Sources: Miroslav Vítek, Ivana Sibková, Ivana Jonová, Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

| a | Po cestách Švejkovy budějovické anabáze | 2020 |

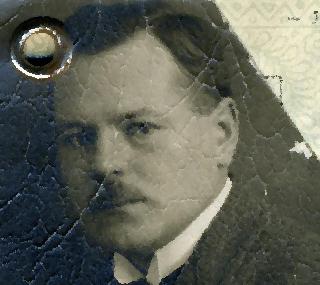

| Jew Herrman, Robert |  | ||||

| *27.12.1885 Lipnice - †1943 Auschwitz | ||||||

| ||||||

Passport photo from 1921

Herrman was a trader in Vodňany who bought military equipment that he sold in the surrounding villages. In the opinion of the wanderer who accompanied Švejk from Štěkno to Švarcenberský ovčín he would surely buy Švejk's uniform.

Background

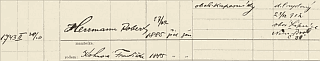

Herrman was not an uncommon surname but is not entered under Vodňany in the address book from 1915[a]. Miroslav Vítek did however get a step closer by investigating the census records from 1910 and here a Jew named Robert Herman is listed[b]. He was a merchant and former travelling salesman who now traded in textiles in Vodňany. He lived in Husova ul. č.p. 60[x]. Herrman was actually born at Lipnice and this could explain why Hašek knew about him.

Vítek’s meticulous research has opened the door for more specific investigations in newspapers and not the least in the Czech Holocaust archive[c]. Based on these sources one can in rough terms outline the life-story of the textile trader from Vodňany.

From Lipnice to Bavaria

Robert Herrmann (also written Hermann, less often Herman) was born in Lipnice 27 December 1885 with Heimatrecht Lipnice, okres Německý Brod. He was a son of Sigmund Herrmann and Aloisie Louisa (née Schwenger) and was the second born of eight siblings. His father was born 6 January 1859 in (Volichov 17) 2 km from Lipnice and his mother in nearby Kejžlice 1 January 1861[m]. Munich 1907, sentenced for petty fraud

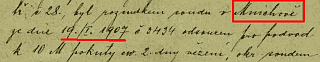

Little is known about his childhood, teenage years, education and military service. He was due for compulsory military service from 1906. Surprisingly the first trace of him comes from abroad as he in Munich on 19 January 1907 was found guilty of fraud and sentenced to two days in prison and a 10 Mark fine[c].

Vodňany

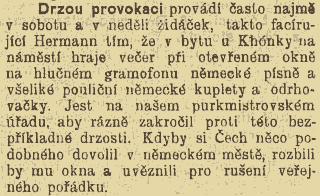

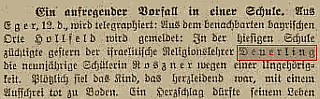

Exactly when he moved to Vodňany is not knows, but it is firmly established that he married Františka Khonová here on 23 February 1908[c]. His bride was from Vodňany itself, born 8 May 1885, and like her husband she was of Jewish confession. A brazen provocation is often being carried out, especially on Saturdays and Sundays, by a little Jewboy Hermann, as he revels in an apartment by Khónka on the square in the evening with the window open and on a loud gramophone plays German songs and various German street vaudevilles and timeworn tunes. It is up to our burgomaster’s office to take resolute action against this unprecedented impudence. If a Czech were to dare something similar in a German town, they would break his windows and jail him for disturbing public peace. , 18.4.1908 (tr. Zenny Sadlon)

Soon after the name of the newly-wed merchant appeared in the local newspaper Jihočeské ohlasy (Týn nad Vltavou). Already on 18 April 1908 they wrote about a “brazen provocation” in a flat on the square židáček* Hermann often played German music loudly on a gramophone, with a window to the square open. "If a Czech allowed himself something similar in a German town he would have his windows broken and would have been jailed for breach of public peace" the newspaper noted[d]. This seems to have been the start of an ongoing quarrel between this newspaper and Herrmann.

* židáček: Derogatory term for Jew.

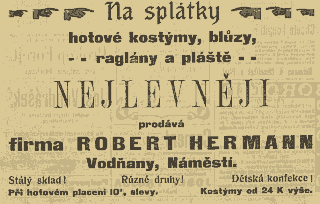

The next recorded incident happened on 13 May 1909 on a local market. Hermann had an argument with Kateřina Zimerhanzlová from Budějovice and was abused as an "impertinent and rude Jew who deserved a few slaps in the face". He sued here for libel and won the court case[e]. Jihočeské ohlasy however sided with the woman and also refused to print the comments that Herrmann’s lawyer, dr. Kučera, sent to the paper (they were according to the law obliged to do so). Herrmann then sued the paper because of this refusal and in addition for libel. Again the court agreed and afterwards he publicly thanked dr. Kučera for having restored his honour. This was through an advert in Šumavské proudy, printed on 12 February 1910[f]. , 15.10.1911

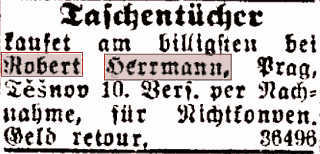

His business was however less successful and in December 1910 his firm went bankrupt[g]. This was reported in Jihočeské ohlasy who gloated and ironically reported that Herrmann now was well again after having been ill[j]. Still he seems to have started up again later that year because he advertised both in 1911 and until March 1912, even in Prager Tagblatt. Jihočeské ohlasy appears to have conducted a smear campaign against Herrmann. That he was a German chauvinist appears unlikely as the during the census in 1910 reported his mother tongue as Czech[x]. He was even referred to as "the ill-reputed merchant"[h]. Smear campaign or not: he did not have an entirely clean record because on 19 July 1911 he was sentenced to 14 days in jail at the Písek district court[c].

Prague

,21.12.1912

After four turbulent years in Vodňany the young couple moved to Prague where they from 13 September 1912 are registered with domicile Praha II., Těšnov 1743/10[i]. The next year they lived in Eliščina třída 1503/28 (now Revoluční) where their first son was born. In Prague, Herrmann started modestly by selling handerchiefs[k], exactly like he did towards the end in Vodňany. He seems to have expanded his business gradually. The couple had three sons: Jiří, Bedřich and Zdeněk, born in 1913, 1915 and 1919 respectively.

We have yet to see any documents that prove if Herrmann ever did military service or was called up during the war. In 1921 he applied for and was granted a passport and the photo of him used on this web page is from related documents, stored in the police archives. In 1930 the family still lived in Praha II., Revoluční třida 1503/28. In 1937 their address was Hlubočepy 369, a detached dwelling on the southern outskirts of Prague, and this is where they lived until they were deported by the Nazis.

Deported and murdered

Police records, 1938.

For the Herrmann family and other Jews the Nazi occupation from March 1939 onwards had tragic consequences. Already towards the end of the year the police had collected information that classified him as a Jew. Imprisonment followed on 4 December 1941 as he was accused of illegal trade with textiles, which surely was a mere pretext. On 17 December he was transported to Terezín (Theresienstadt) and on 6 September 1943 onwards to Auschwitz where he was murdered[c]. His wife was in the same transport and suffered the same gruelling fate. Their sons Zdeněk and Jiří were also murdered by the Nazis but the fate of Bedřich is not known. His father Sigmund, also a merchant, was deported and died in Terezín at the age of 83. His mother Aloisie had passed away already in 1925.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „Tak ten si nech. V tom se na venkově chodí. Potřebuješ kalhoty a kabát. Až budeme mít ten civil, tak kalhoty a kabát prodáme židovi Herrmanovi ve Vodňanech. Ten kupuje všechno erární a zas to prodává po vesnicích.

Sources: Miroslav Vítek

Literature

- Siegmund Herrmann

- Františka Herrmannová

- Jiří Herrmann

- Zdeněk Herrmann

- Žalobu26.6.1909

- Panu dru. Kučerovi17.9.1909

- Podařená reklama15.10.1909

- Na splátky15.10.1911

- Packware in Taschentücheln3.2.1912

| a | Chytilův úplný adresář Království Českého | 1915 | |

| b | Po cestách Švejkovy budějovické anabáze | 2020 | |

| c | Robert Herrmann | ||

| d | Drzou provokaci | 18.4.1908 | |

| e | Nekalá soutěž | 29.5.1909 | |

| f | Díkůvydání! | 12.2.1910 | |

| g | Insolvenzen | 10.12.1910 | |

| h | Ještě Hermann | 2.10.1909 | |

| i | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| j | Vyléčen | 4.3.1911 | |

| k | Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920) | ||

| m | Sigmund Herrmann (1859 - 1942) | ||

| x | Sčitání lidu Vodňany | 1910 |

| Jareš |  | |||

| |||||

Jareš was the grandfather of the pond warden from Ražice, and was executed as a deserter during the Napoleonic wars. It happened in Písek and before he was executed he was hounded through the streets by soldiers and beaten with sticks 600 times. The information is revealed during the conversation at Švarcenberský ovčín.

Background

This is another Jareš that seems to be inspired by the author's grandfather. See pondwarden Jareš.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Z Ražic za Protivínem syn Jarešův, dědeček starýho Jareše, baštýře, dostal za zběhnutí prach a volovo v Písku. A před tím, než ho stříleli na píseckých šancích, běžel ulicí vojáků a dostal 600 ran holema, takže smrt byla pro něho vodlehčením a vykoupením.

| Fürst Schwarzenberg (st.) |  | ||||

| ||||||

Adolf Josef Schwarzenberg, detail - portrét z oslav zlaté svatby, 1907

Český svět, 14.6.1907

Schwarzenberg (st.) (the old prince Schwarzenberg) is mentioned by the old shepherd in Švarcenberský ovčín. He tells us that at least the old Schwarzenberg used to travel around in an ordinary carriage but nowadays the young prince drives around in an auto-mobile.

Background

Schwarzenberg (st.) probably refers to Adolf Joseph Schwarzenberg (1832-1914), head of the Krumlov-Hluboká family branch (primogenitura) and the owner of the Libějovice estate to which Hašek's presumed Švarcenberský ovčín belonged[a].

He is talked about as the old prince Schwarzenberg and the fact that he died in 5 October 1914 at Libějovice at an advanced age fits the conversation at the sheep house. He is referred to in the past tense whereas the young prince is talked about in present tense.

Adolf assumed ownership of the estates of Netolice, Libějovice and Protivín already in 1857, the rest followed after his father's death in 1888. He also enjoyed a military career, attaining the rank of major. He participated in the battle of Solferino 24 June 1859. After the battle he retired from the army and dedicated himself to politics and management of his estate. He raised 9 children, and his son Johann Nepomuk II. succeeded him as head of the estate.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Dyť vona i ta naše vrchnost už roupama nevěděla co dělat.Starej pán kníže Švarcenberg, ten jezdil jen v takovým kočáře, a ten mladej knížecí smrkáč smrdí samým automobilem. Von mu pánbůh taky ten benzin vomaže vo hubu.“

Sources: Miroslav Vítek

Literature

- Kníže Adolf Josef Schwarzenberg zemřel7.10.1914

- Knížecí Schwarzenbergský šematismus I. a II. majorátu na rok 1894

| a | Po cestách Švejkovy budějovické anabáze | 2020 |

| Fürst Schwarzenberg (ml.) |  | |||

| |||||

Adolf Johann Schwarzenberg

Schwarzenberg (ml.) (the young prince Schwarzenberg) is mentioned by the old shepherd in Švarcenberský ovčín. He tells us that at least the old Schwarzenberg used to move around in an ordinary carriage but nowadays the young prince drives around in an auto-mobile, and that the Good Lord will rub his snout in petrol one day.

Background

Schwarzenberg (ml.) may refer to Johann Nepomuk Schwarzenberg (1860-1938) or rather his son Adolf Johann (1890-1950). Both were car enthusiasts and very early they embraced the novel mean of transport.

Both were in turn heads of the Krumlov-Hluboká branch of the family (primogenitura), and they owned the sheep farm by Bavorov that we assume is Hašek's Švarcenberský ovčín. Johann bought his first car in 1905 and later added several more[a]. Antonín Nikendey was amongst several sources who confirmed that the son Adolf was an auto-mobile enthusiast in his younger years[b].

Adolf seems to be the best candidate, mostly due to his young age (in 1915 he was 25). In a book fromm 2008 his nephew Karel Jan stated that it actually was Adolf who inspirerte HAS[a], a claim that for obvious reasons is impossible to verify. For the old shepherd even his father would have been a youngster (Johann was 55 in 1915). In 1915 Johann Nepomuk II. owned the estate, his son was serving in the army.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Dyť vona i ta naše vrchnost už roupama nevěděla co dělat. Starej pán kníže Švarcenberg, ten jezdil jen v takovým kočáře, a ten mladej knížecí smrkáč smrdí samým automobilem. Von mu pánbůh taky ten benzin vomaže vo hubu.“

Sources: Miroslav Vítek

| a | Po cestách Švejkovy budějovické anabáze | 2020 | |

| b | K narozeninám JUDr. Adolfa Schwarzenberga | 1990 |

| Kořínek |  | |||

| |||||

Kořínek was arrested for sedition in Skočice after saying that after the war one would get rid of Emperors, and that the nobility would have their estates confiscated. This is what the old shepherd at Švarcenberský ovčín told Švejk and the tramp who was there with them.

Background

Attempts to identify any person who may have inspired Hašek to introduce this figure have proved futile. According to the 1910 census no person with this surname lived in Skočice[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „Na to se mu, hochu, teď každej vykašle,“ rozdrážděně promluvil ovčák, „máš bejt při tom, když se sejdou sousedi dole ve Skočicích. Každej tam má někoho, a to bys viděl, jak ti mluvějí. Po tejhle válce že prej bude svoboda, nebude ani panskejch dvorů, ani císařů a knížecí statky že se vodeberou. Už taky kvůli takovej jednej řeči vodvedli četníci nějakýho Kořínka, že prej jako pobuřuje. Jó, dneska mají právo četníci.“

| a | Sčitání lidu Skočice | 1910 |

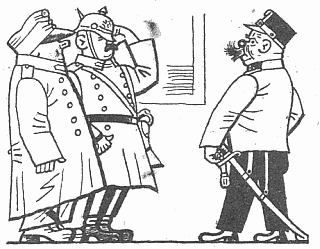

| Wachtmeister Flanderka |  | |||

| |||||

,10.2.1924

Flanderka guarding Švejk in Putim

Kulturní adresář ČSR, 1934-1936

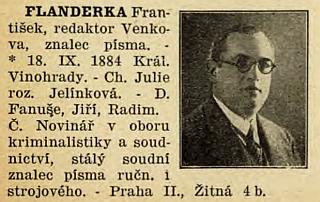

Flanderka was head of Gendarmeriestation Putim and suspected Švejk of being a Russian spy. He considered himself a master of interrogation techniques and it soon became clear to him that Švejk was indeed a spy. The more he tanked up, the clearer it all became. He and his deputy also made complete fools of themselves with extremely seditious talk when they had enjoyed a drop too much. Austria was going to loose the war, a Russian prince would become king of Bohemia and Emperor Franz Joseph I., was shitting all over Schönbrunn. The petrified old servant Pejzlerka who had witnessed it all, had to swear never to tell a living soul what she had heard. From the dialogue it is also apparant that Flanderka had served in Putim for 15 years and that he had at least two assistants.

Background

Considering that the whole setting of Putim has no obvious historical base one would not expect to find any real life prototype for Flanderka. This is merely confirmed by the fact that this surname didn't appear in Putim in the 1910 census, nor was any Flanderka listed in the k.k. Gendarmerie.

Flanderka is a quite common surname and Hašek might have known a few of them and taken the liberty to borrow the name. One person that the author of The Good Soldier Švejk probably knew was the illustrator Jaroslav Flanderka (1877-?) who from 1909 onwards contributed to Humoristické listy, a publication that at times also published Hašek's stories[a].

An even more tangible connection is the typographer František Josef Flanderka (1884-?)[c]. According to Julie Flanderková he was a friend of Hašek until the two fell out in the pub Maxim on the periphery of Malá Strana towards Smíchov. Flanderková (she seems to have been his wife) was of the opinion that Hašek took revenge by sticking the name Flanderka to the stupid policeman in Putim[b]. Flanderka eventually became editor of Venkov.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Četnickému strážmistrovi Flanderkovi se situace, čím déle psal tou podivnou úřední němčinou, vyjasňovala, a když skončil: „So melde ich gehorsam, wird der feindliche Offizier heutigen Tages, nach Bezirksgendarmeriekommando Písek, überliefert,“ usmál se na své dílo a zavolal na četnického závodčího. „Dali tomu nepřátelskému důstojníkovi něco jíst?“

Literature

| a | J. Flanderka | 18.4.1910 | |

| b | Haškova pomsta | Julie Flanderková | |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 |

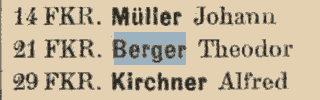

| Oberleutnant Berger |  | ||||

| ||||||

,10.2.1924

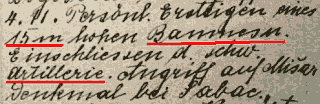

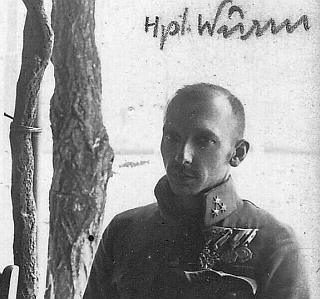

Sagner climbed a 15 metres tall tree to assist the heavy artillery in aiming the fire. From Sagner's "Vormerkblatt".

© VHA

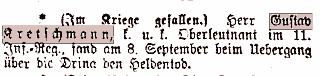

Berger was a duty-conscious obrlajtnant from the artillery who according to Národní politika had established an observation post in a tree, and hid there for two weeks to avoid captivity. When his own troops returned he fell down and killed himself. This was a story that Wachtmeister Flanderka told his assistant at Gendarmeriestation Putim.

Background

Berger was a very common surname and there were more than 50 officers with this name in k.u.k. Heer alone, most of them serving with the infantry. In 1914 five Berger with the rank Oberleutnant were listed in Schematismus[a]. In addition there were a number of lieutenants that may have been promoted by the time the plot reached Putim, probably in early 1915.

In the artillery there was no Oberleutnant Berger in 1914 but in the Rangliste for 1916 a Theodor Berger is listed in Feldkanonenregiment Nr. 21. He was however promoted on 1 July 1915 so Wachtmeister Flanderka could not have read about him as senior lieutenant earlier that year. On 1 March Richard Berger in Feldkanonenregimnet Nr. 42 had been promoted to senior lieutenant (reservist).

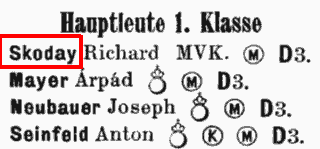

Sagner in the tree

The story has a curious parallel to an episode involving Hašek's future commander Čeněk Sagner. In Serbia on 4 November 1914 he climbed a 15 metres tall tree to assist the heavy artillery with aiming the fire[b]. Such a spectacular deed may well have been retold and caught Hašek's ear in 1915 when veterans related stories and hearsay from the campaign previous autumn. Sagner's rank at the time was indeed senior lieutenant.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Kdyby bylo v Rakousku takové nadšení... ale nechme toho raději. I u nás jsou nadšenci. Četli v ,Národní politice’ o tom obrlajtnantovi Bergrovi od dělostřelectva, který si vylezl na vysokou jedli a zřídil si tam na větví beobachtungspunkt?

| a | Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 391) | 1914 | |

| b | Jednadevadesátníci | 2018 |

| Wachtmeister Bürger |  | ||||

| ||||||

Bürger was Wachtmeister Flanderka's predecessor as head of k.k. Gendarmerie in Putim until fifteen years ago, in other words around 1900. He never interrogated anyone, just sent them on to Písek.

Background

It has not been possible to find any real life parallel/inspiration for this policeman. It would surely be futile in any case as even Gendarmeriestation Putim itself is an invention.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Vzpomněl si na svého předchůdce strážmistra Bürgera, který se zadrženým vůbec nemluvil, na nic se ho netázal a hned ho poslal k okresnímu soudu s krátkým raportem: „Dle udání závodčího byl zadržen pro potulku a žebrotu.“ Je to nějaký výslech?

| Pepík Vyskoč |  | ||||

| ||||||

Flanderka instructs Pepík Vyskoč

,10.2.1924

Pepík Vyskoč was a village idiot who Wachtmeister Flanderka tried to hire as an informer. He was told to report anyone who said that the Emperor was a piece of cattle. Pepík took this literally, he told others that Flanderka had said that the Emperor was cattle and that the thing (the war) couldn't be won. Pepík was arrested and sentenced to twelve years by the military court in Prague. He got the nick-name because he bleated like a goat and jumped into the air when someone talked to him.

Background

This is a character that no doubt inspired by Zdenko Václav Kompit, better known as Venca Vyskoč. The connection was first pointed out to me by Sergey Soloukh in 2015 and Jaroslav Šerák provided further details in 2022.

A dubious link to Lipnice

Far less credible is Vladimír Stejskal (1953) and his claim that the inspiration was a character from the area around Lipnice. The evidence is weak: not much more than pure hearsay and the fact that Hašek wrote this part of the novel just after arriving at Lipnice on 25 August 1921.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Toho si dal zavolat a řekl k němu: „Víš, Pepku, kdo to je starej Procházka?“ „Méé.“„Nemeč, a pamatuj si, že tak říkají císaři pánu. Víš, kdo je to císař pán?“ „To je číšaš pán.“ „Dobře, Pepku. Tak si pamatuj, že když někoho uslyšíš mluvit, když chodíš po obědech od domu k domu, že je císař pán dobytek nebo podobně, hned přijď ke mně a oznam mně to.

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák, Sergey Soloukh, Karel Ladislav Kukla, Augustin Knesl

Also written:Pepek VyskočParrottPepku HoppReinerJoey JumpSadlon

Literature

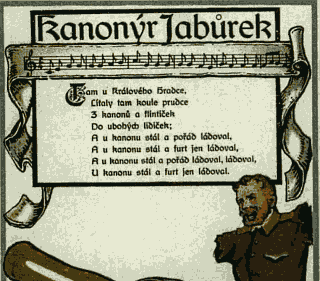

| Starej Procházka |  | |||

| |||||

Zlatá Praha, 21.7.1901

Starej Procházka is mentioned by Wachtmeister Flanderka when he recruits Pepík Vyskoč as an informer. He repapears soon after when one of the drunk policemen at Gendarmeriestation Putim exclaims that the emperor and king must is kept locked up in the toilet to prevent him from shitting all over Schönbrunn.

Background

Starej Procházka was a Czech nickname for Emperor Franz Joseph I. In 1901 he visited Prague and pictures of him appeared walking on Most císaře Františka I., now Most Legii. One of the pictures allegedly had the title Procházka na mostě but it has not been established which picture and where it was printed. The photos were from the opening of the bridge on 14 June. "Procházka" is a common Czech surname which rougly means "walk" (noun) or "walkabout".

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Toho si dal zavolat a řekl k němu: „Víš, Pepku, kdo to je starej Procházka?“ „Méé.“„Nemeč, a pamatuj si, že tak říkají císaři pánu. Víš, kdo je to císař pán?“

[II.2] ,Pamatujou, bábo, že každý císař a král pamatuje jen na svou kapsu, a proto vede válku, ať je to třebas takový dědek jako starý Procházka, kterého nemohou už pustit z hajzlu, aby jim nepodělal celý Schönbrunn"...

Also written:Old ProcházkaEnglishAlte ProchazkaReiner

Literature

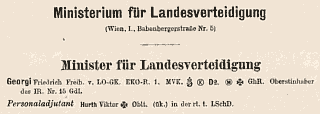

| Minister von Georgi, Friedrich |  | |||

| *27.1.1852 Praha - †23.6.1926 Wien | |||||

| |||||

Friedrich Freiherr von Georgi, 1914

Schematismus der K. K. Landwehr..., 1914

1914

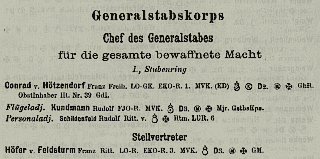

Minister für Landesverteidigung (minister of land defence) is mentioned in the bad dream that Wachtmeister Flanderka has regarding all the directives sent from k.k. Ministerium für Landesverteidigung.

Background

Because Švejk's anabasis by Putim necessarily must have taken place in early 1915, the minister who haunted Wachtmeister Flanderka in his dreams was no doubt Friedrich Freiherr von Georgi. He was head of k.k. Ministerium für Landesverteidigung (i.e. secretary of defence) in Cisleithania from 1907 to 1917, and was thus formally head of both k.k. Landwehr and k.k. Gendarmerie.

Georgi was regarded an excellent organiser and also a person who was capable of operating both in the military and in politics. These seem to have been the reasons why his application to serve at the front where rejected[a]. At the outbreak of war his rank was general. Friedrich von Georgi was born in Prague and hailed from a family of officers.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Neustále očekával inspekci, vyšetřování. V noci zdálo se mu o provaze, jak ho vedou k šibenici. A ještě naposled se ho sám ministr zemské obrany pod šibenicí táže: „Wachmeister, wo ist die Antwort des Zirkulärs No 1789678/23792 X.Y.Z.?“

| a | Friedrich Freiherr von Georgi | 2001 - 2016 |

| Gendarm Rampa |  | ||||

| ||||||

Rampa was a gendarm (četnik) in Putim who was on inspection-duty around the neighbouring villages when Švejk was locked up here, but was right now playing cards with some shoemakers at U černého koně in Protivín, explaining during the breaks that Austria had to win (the war).

Background

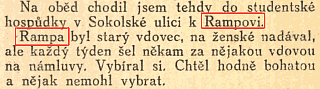

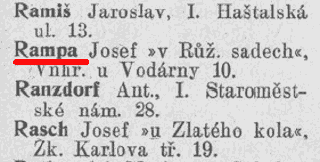

Rampa is a petty rare surname and most of them are now (2021) concentrated in a limited area west and south of Praha[a]. There was obviously no gendarm with this surname at Gendarmeriestation Putim simply because this police station didn't exist. Nor is there any sign of any Rampa at nearby police stations like Protivín. Thus we can assume that Hašek simple borrowed the name more or less at radom and assigned it to a policeman. It probably has the same origin as pubkeeper Rampa from Vinohrady (he appears later on in the chapter).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Strážmistr zůstal sedět na strážnici vedle Švejka na kavalci prázdné postele četníka Rampy, který měl do rána službu, obchůzku po vesnicích, a který v tu dobu klidně seděl „U černého koně“ v Protivíně a hrál s obuvnickými mistry mariáš, vykládaje v přestávkách, že to Rakousko musí vyhrát.

| a | Příjmení: 'Rampa', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 |

| Pejzlerka |  | ||||

| ||||||

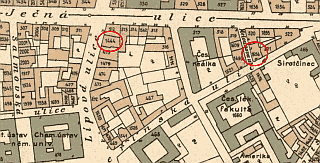

Where Peisler lived in 1907 and 1910

Pejzlerka was an old woman who served at Gendarmeriestation Putim. During the night that Švejk was interned here she shuttled back and forth to Na Kocourku to fetch beverages for the gendarmes and Švejk. Unfortunately she overheard the politically suspect conversation between the drunk gendarmes and the next morning she had to swear by the crucifix not to tell a living soul.

Otherwise it is revealed that she hadn't been paid for three years. The reason was that Wachtmeister Flanderka knew that her son was a poacher and was thus able to blackmail her.

Background

Pejzlerka is neither a Czech first name nor a surname. It is therefore logical to assume that it was a nickname for some woman Pejzler or similar. Still not even this name is found in name databases. The German phonetically equivalent Peisler does however exist, despite it being rare.

In the Prague address books from 1907 and 1910 only one man with the surname Peisler is listed. František Peisler lived in an area of Praha II. that Hašek knew very well as it was his stomping ground and he also frequented the area a lot during the whole pre-war period. Peisler's address in 1907 was Melounová ul. 1654/2[a] and in 1910 he had moved to Lipová ul. 1444/18[b], a stone's throw further down towards Vltava.

Everything considered it could be that Peisler's wife or some other female relation was nicknamed "Pejzlerka" in Czech. Still it would be far fetched to conclude that Hašek knew (about) her and subsequently borrowed the name, but is remains a possibility.

Another possible source of inspiration is some variation of the surname Pejzl. The name is more widespread than Peisler although it is not found in Prague's police register or in the address books. Interesting is also the fact that several Pejzl's live in the area around Lipnice[c] and surely also did so in 1921.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] A bába Pejzlerka, která jim posluhovala, se opravdu proběhla. Po večeři se cesta mezi četnickou stanicí a hospodou „Na Kocourku“ netrhla. Neobyčejně četné stopy těžkých velkých bot báby Pejzlerky na té spojovací linii svědčily o tom, že strážmistr si vynahražuje plnou měrou svou nepřítomnost „Na Kocourku“.

| a | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1907 | |

| b | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1910 | |

| c | Příjmení: 'Pejzl', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 |

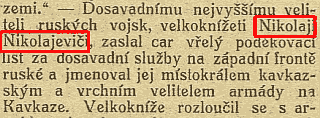

| Nicholas Nikolaevich |  | ||||

| *18.11.1856 St.Petersburg - †5.1.1929 Antibes | ||||||

| ||||||

,25.1.1907

,9.9.1915

,20.6.1915

Nicholas Nikolaevich is mentioned when it is revealed what unpatriotic views were uttered during the drinking binge at Gendarmeriestation Putim. Nicholas Nikolaevich would soon be in Přerov, Wachtmeister Flanderka is reported to have said. Hi assistent concluded for his part the Nikolaj would become Czech king.

Background

Nicholas Nikolaevich was a grand duke from the Romanov house and Russian commander in chief from the outbreak of war until 5 September 1915 (23.8) when Tsar Nicholas II personally took charge. This was a result of the setbacks suffered during the summer of 1915 when the Russians were forced out of Poland and Galicia. Nicholas was subsequently appointed viceroy and commander at the Caucasus front[a].

As a curiosity we can mention that Nicholas featured in the poetry collection Die eiserne Faust by Greinz, together with Sir Edward Grey, Churchhill and many others![b]

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Nakláněje se k uchu strážmistra, šeptal: „Že jsme všichni Češi a Rusové jedna slovanská krev, že Nikolaj Nikolajevič bude příští týden v Přerově, že se Rakousko neudrží, aby jen, až bude dál vyšetřován, zapíral a pletl páté přes deváté, aby to vydržel do té doby, dokud ho kozáci nevysvobodí, že už to musí co nejdřív prasknout, že to bude jako za husitských válek, že sedláci půjdou s cepy na Vídeň, že je císař pán nemocný dědek a že co nejdřív natáhne brka, že je císař Vilém zvíře, že mu budete do vězení posílat peníze na přilepšenou a ještě víc takových řečí...“

[II.2] "Oni se také pěkně vyjádřili," přerušil ho strážmistr, "kde jen přišli na takovou hloupost, že Nikolaj Nikolajevič bude českým králem?"

Also written:Nikolaj NikolajevičczNikolai NikolajewitschdeНиколай Николаевичru

Literature

| a | Zaren overtar selv overkommandoen | 8.9.1915 | |

| b | Kriegs-Marterln | 20.6.1915 |

| Hus, Jan |  | |||

| *1369-1370? Husinec - †6.7.1415 Konstanz | |||||

| |||||

Husitské válečnictví

, 1938

Jaroslav Hašek, Průkopník, 27.3.1918

© VHÚ

Hus is mentioned indirectly through the term Hussite Wars, as part of the conversation between the drunk policemen at Gendarmeriestation Putim.

Background

Hus was a famous Czech theologician, philosopher and eventually Church reformer. He was one of the first who openly criticised the Catholic Church, and he subsequenlty was burned as a heretic. After his death the Hussite movement had a profound impact on the course of Czech history and until this day Hus remains an important national symbol.

The Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars was a series of conflicts that were played out between 1419 and 1434 in the aftermath of the death of Hus. The Hussite movement rebelled against the Catholic Church and the German-Roman Emperor. These in turn dispatched four crusades against Bohemia that were all repelled. The wars also included conflicts between moderate and radical Hussites where the moderates in the end allied with the Catholics and the Emperor. The radicals centred around Tábor (the so-called Táborité) and were in the beginning led by the famous commander Jan Žižka, and like Hus a Czech national legend.

Hus and Czech nationbuilding

During the fight for Czech independence Hus and the Hussites became an important symbol. The first regiment of České legie (the unit that Hašek served in) was in August 1917 given the name 1. střelecý pluk Jana Husi. Hussite leaders like Jan Žižka, Prokop Holý and King Jiří z Poděbrad also had regiments named after themselves. Jaroslav Hašek also referred to the, in his propaganda writing from 1916 onwards and even after he became a Communist in 1918[a]. The Hussite, specifically the Taborite ideals of equality obviously inspired the communists. In inter-war Czechoslovakia and also during Communist rule the Hussites were still revered. In the current Czech Republic more than 100 street carry his name. If his followers are included the number will reach several hundreds.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Nakláněje se k uchu strážmistra, šeptal: „Že jsme všichni Češi a Rusové jedna slovanská krev, že Nikolaj Nikolajevič bude příští týden v Přerově, že se Rakousko neudrží, aby jen, až bude dál vyšetřován, zapíral a pletl páté přes deváté, aby to vydržel do té doby, dokud ho kozáci nevysvobodí, že už to musí co nejdřív prasknout, že to bude jako za husitských válek, že sedláci půjdou s cepy na Vídeň, že je císař pán nemocný dědek a že co nejdřív natáhne brka, že je císař Vilém zvíře, že mu budete do vězení posílat peníze na přilepšenou a ještě víc takových řečí...“

Literature

| a | K českému vojsku | Jaroslav Hašek | 27.3.1918 |

| Butcher Chaura |  | |||

| |||||

, 1910

Chaura was a butcher from Kobylisy who circled around the statue of Palacký at Moráň, thinking it was an endless wall. This is revealed in a story Švejk tells his guard on the way from Putim to Písek.

Background

Chaura was a rare surname and none of the three that are listed in the address book from 1910 were butchers or from Kobylisy[a]. In 1907 the town had two butchers: Josef Koníček and František Smetana.

Still it can't be ruled out that Hašek knew some Chaura and borrowed his name. One such candidate is the antique trader František Chaura who had his outlet next to c.k. policejní ředitelství (an institution the author of The Good Soldier Švejk knew very well). One further notes that the Palacký monument was unveiled 1 July 1912 so if the story with Chaura has any real backround it must have happened after this date.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „To byl bych si nikdy nemyslil,“ vykládal Švejk, „že taková cesta do Budějovic je spojena s takovejma vobtížema. To mně připadá jako ten případ s řezníkem Chaurou z Kobylis. Ten se jednou v noci dostal na Moráň k Palackýho pomníku a chodil až do rána kolem dokola, poněvadž mu to připadalo, že ta zeď nemá konce.

| a | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1910 |

| Palacký, František |  | |||

| *14.6.1798 Hodslavice - †26.5.1876 Praha | |||||

| |||||

, 12.6.1908

Palacký is mentioned by Švejk in the story about butcher Chaura who walked round the Palacký-monument at Moráň the whole night.

In [III.2] in Budapest he is quoted by Leutnant Dub as follows: "if there weren’t Austria we’d have to create it.

Background

Palacký was a Czech historian and politician who played a pivotal role in the Czech National Revival. He was also called otec národa, the father of the nation. He was loyal to the Empire, initially a proponent of the so-called Austroslavism, although he became more radical after Ausgleich in 1867. Like most Czechs he resented that Hungary achieved a special status within the Habsburg Empire.

The Palacký monument is located on the eastern bank of Vltava, at Palackého náměstí. It was unveiled in 1 July 1912[a] in a grand ceremony, attended by Prague's notabilities.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „To byl bych si nikdy nemyslil,“ vykládal Švejk, „že taková cesta do Budějovic je spojena s takovejma vobtížema. To mně připadá jako ten případ s řezníkem Chaurou z Kobylis. Ten se jednou v noci dostal na Moráň k Palackýho pomníku a chodil až do rána kolem dokola, poněvadž mu to připadalo, že ta zeď nemá konce.

[III.2] To budou také taková hovada, jako jste vy!... Čím byli?... U trénu?... Nu dobře... Pamatujte, že jste vojáci... Jste Češi?... Víte, že řekl Palacký, že kdyby nebylo Rakousko, že bychom ho musili vytvořit... Abtreten...!“

| a | Slavnost odhalení pomníku Palackého | 1.7.1912 |

| Rittmeister König |  | ||||

| ||||||

,24.2.1924

Kolský seems to have served diligently, just like König

, 16.11.1918

König was station commander at Bezirksgendarmeriekommando Pisek, and very diligent, an outstanding bureaucrat. “If we want to win the war,” he said, “an ‘a’ must be an ‘a’, a ‘b’ a ‘b’, and everywhere there has to be a dot over the ‘i’.” He received Švejk and correctly sent him south to join his regiment which he for many days had looked for in vain.

Background

König is clearly an invented person, nor would normally a Rittmeister (captain) be in command of a district command. The position in question was in 1915 held by Wachtmeister Antonín Kolský[a]. The chief of the unit they reported to did however have this rank: Rittmeister Rotter.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] A opravdu bylo to hrozné, když strážmistr poslal pro velitele stanice, rytmistra Königa. První slovo rytmistrovo bylo: „Dýchněte na mne.“ „Teď to chápu,“ řekl rytmistr, zjistiv nesporně situaci svým bystrým, zkušeným čichem, „rum, kontušovka, čert, jeřabinka, ořechovka, višňovka a vanilková. Pane strážmistr,“ obrátil se na svého podřízeného, „zde vidíte příklad, jak nemá četník vypadat. Takhle si počínat je takový přečin, že o tom bude rozhodovat vojenský soud. Svázat se s delikventem želízky. Přijít ožralý, total besoffen. Přilézt sem jako zvíře! Sundejte jim to!“

| a | Chytilův úplný adresář Království Českého | 1915 |

| Wachtmeister Matějka |  | |||

| |||||

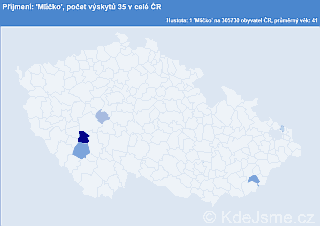

The surname Matějka is and was very common in Bohemia

KdeJsme.cz,2017

Police report. Hašek arrested after causing trouble on Příkopy 1 January 1905. Translated by Břetislav Hůla.

© LA-PNP

Matějka was master sergeant at Bezirksgendarmeriekommando Pisek. He was keen on getting off for a game of "Schnaps" down by the Otava but Rittmeister König held him back. This annoyed Matějka who thought to himself that the police chief could kiss his arse with all these reports.

Background

has not been possible to identify with respect to a possible real-life model. Neither the address book from 1915 nor the census from 1910 has any policeman Matějka listed in Písek. This should come as no surprise as the Putim to Písek sequence in The Good Soldier Švejk is (in a geographical sense) hardly based on real events or the author's experiences.

The author may however still borrowed the name and assigned it to his fictional policeman. Matějka is a very common surname[a] and we know that several of them served with Jaroslav Hašek in IR. 91 in 1915, amongst them an officer. See Korporal Matějka for more information about them.

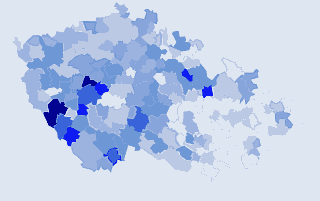

A source of inspiration that is far more plausible than some name from IR. 91 is the policeman Anton Matějka. At 3 AM on 1 January 1905 he arrested a drunk and disorderly Hašek at Na Příkopě (Am Graben)[b]. Otherwise the address books and police records of Prague reveal that a large number of Matějkas lived in the city so Hašek could have known a few of them.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Rytmistr studoval „bericht“ četnického strážmistra z Putimě o Švejkovi. Před ním stál jeho četnický strážmistr Matějka a myslel si, aby mu rytmistr vlezl na záda i se všemi berichty, poněvadž dole u Otavy čekají na něho s partií „šnopsa“.

Sources: Radko Pytlík, Břetislav Hůla

| a | Příjmení: 'Matějka', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| b | Toulavé house | 1971 |

| Hercules |  | |||

| |||||

Hercules capturing the three-headed dog Cerberus

Hercules is mentioned indirectly by Rittmeister König when Švejk tells him about his efforts to join his regiment. The term he used was "a Herculian job".

Background

Hercules is the latin name of Heracles, a Greek demigod, son of Zeus, known for his strength. The text in The Good Soldier Švejk refers to the Twelve Labours of Heracles, each and one of them in turn a huge challenge.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „To byla herkulovská práce,“ řekl konečně, když se zalíbením naslouchal Švejkovu líčení, jak ho to mrzí, že se nemohl tak dlouho dostat k pluku, „na vás musela být mohutná podívaná, když jste se kroutil kolem Putimi.“

Also written:HéraklésczHerculesla

| Pubkeeper Rampa |  | ||||

| *30.9.1854 Suchodol - †? | ||||||

| ||||||

Z mých vzpomínek na Jaroslava Haška, , 1925

, 1910

Rampa was according to Švejk an elderly pub landlord in Vinohrady who turned a deaf ear when guests wanted to drink on a tab. By this Švejk informed Rittmeister König that there would have been no point in telling Wachtmeister Flanderka his name or what regiment he belonged to.

Background

Rampa (Josef) was a pub landlord that Hašek knew well. Hájek wrote that Rampa managed a pub in Sokolská ulice that was mainly visited by students. He was an elderly widower and his older sister cooked for the students. Rampa was constantly looking for a new wife, and preferably a widow with money. He liked Hašek because the young author took time to listen to him[a]. Rampa was in fact reluctant to let bar guests run up debts. Hájek doesn't say anything about what year(s) he and Hašek frequented Rampa's pub.

Police registers reveal that Rampa was born in 1854 in Suchodol by Příbram, initially married to Marie (born in 1848) and that he from 1892 to 1914 lived at nine different addresses at Vinohrady[b] and six in Praha II. [c]. None of these addresses were in Sokolská but he might not necessarily have lived at the premises of the pub he managed (although this was the norm at the time). His first wife died in 1898 and he later married Josefa (neé Černá). To judge by the police registers she was a widow.

Church records show that Rampa's father also was a pub landlord, at Suchodol No. 9[d].

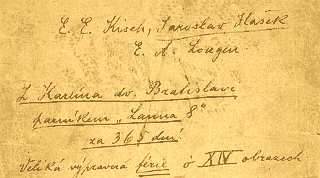

From Karlín to Bratislava in 365 days

,29.12.1921

,30.12.1921

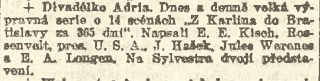

This is a play that was written in 1921, presumably close to the end of the year. It is a farcical story about a roundabout journey from Prague to Bratislava with the steamer Lanna, along the waterways of Europe. The play was first advertised in Tribuna, Prager Presse and Rudé právo on 30 December 1921 and the authors were literally: E.E. Kisch, Rossenvelt pres. U.S.A., J. Hašek, Jules Werenes, E.A. Longen. It was performed at the theatre Adria, the same stage that from 1 November 1921 had hosted Emil Artur Longen's theatre version of The Good Soldier Švejk with Longen as director. In later adverts "Werenes"" and "Rossenvelt"" were for obvious reasons left out.

The manuscript reveals that the script was approved by the police on 29 December 1921 and that the censors had some objetions! Still, there were no major changes. Emil Artur Longen, Jaroslav Hašek and Egon Erwin Kisch are listed as authors[x].

Two names that are familiar from The Good Soldier Švejk feature prominently: Offiziersdiener Mikulášek and pubkeeper Rampa. Incidently these names appeared in the novel around the time when the play was written. In the play Mikulášek is a stoker and main character whereas Rampa is described much in the same way as in the novel. One of the scenes involves Mikulášek being drunk in Rampa's pub!

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] „Proč jste v Putimi neupozornil, že se jedná o omyl?“ „Poněvadž jsem viděl, že je to marný, s ním mluvit. To už říkal starej hostinskej Rampa na Vinohradech, když mu chtěl někdo zůstat dlužen, že přijde někdy na člověka takovej moment, že je ke všemu hluchej jako pařez.“

Sources: Sergey Soloukh

Literature

- Die Reise um Europa in 365 Tagen1921

- Oznámení26.11.1893

- Smichover Actien-Bier19.11.1898

- Hostinec19.11.1898

- Oznámení1.4.1900

- Pan Josef Rampa15.11.1905

- Otevření hostince28.11.1906

- Die Reise um Europa in 365 Tagen1921

| a | Z mých vzpomínek na Jaroslava Haška | 1925 | |

| b | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| d | Pičín (Římskokatolická církev) | 1850-1871 | |

| x | Z Karlína do Bratislavy parníkem Lanna 8 za 365 dní | 29.12.1921 |

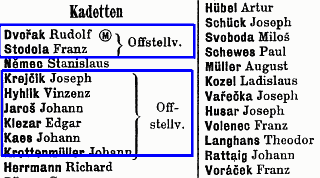

| Fähnrich Koťátko |  | ||||

| ||||||

, 1910

Death of Václav Koťátko Sr.

, 11.11.1912

, 29.10.1913

Koťátko was a junior officer in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 who witnessed Švejk's appearance at Mariánská kasárna in Budějovice, and watched Oberleutnant Lukáš passing out as a result of seeing his servant again. Later he related about the incident, for instance that Švejk saluted during the whole sequence.

Background

In IR. 91 there is no trace of any Koťátko, whether it be in Schematismus, Verlustliste or other available military documents. The surname was moreover virtually non-existent in the regiment's recruitment area[f].

The inspiration for the name is thus more likely to be found in civilian life and the name indeed appears in Hašek's pre-war writing. In Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona he mentions a certain judge Koťátko[a] and he also wrote a story featuring the postal official Koťátko from Rokycany[b].

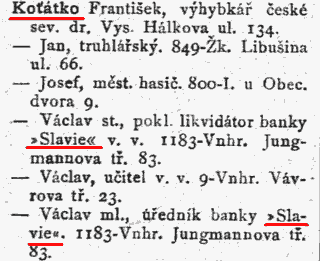

Banka Slavia

They name may well have been borrowed from Václav Koťátko, one or even two men that Hašek surely knew. These two Václav's were father and son, born in 1852 and 1881 respectively, lived in the same house at Vinohrady and both worked at Banka Slavia (where Hašek was employed in 1902 and 1903)[c][d]. Václav jr. must also have been a Fähnrich at some stage because in 1916 he held the rank of Oberleutnant.

A judge in Strakonice

One judge Koťátko did indisputably live and work at the time. This man was Jan Koťátko who from 1905 worked at the district court in Strakonice[e]. Whether or not this person had anything to do with Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona is pure guesswork, but Hašek's judge Koťátko was amongst those who spread the word of the "party" in the countryside[a] so perhaps the connection has some substance.

An apprentice lawyer

Antonín Koťátko is also a person who may, at a push, be the judge from Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. In 1906 he was an apprentice lawyer who lived in Balbinova ulice at Vinohrady[g]. In this street the pub U zlatého litru was located, the place where the "party" allegedly was founded.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] U celé té scény byl praporčík Koťátko, který později vypravoval, že po tom hlášení Švejkově nadporučík Lukáš vyskočil, chytil se za hlavu a upadl naznak na Koťátko, a že když ho vzkřísili, Švejk, který po celou tu dobu vzdával čest, opakoval: „Poslušně hlásím, pane obrlajtnant, že jsem opět zde!“

| a | Jiná organizační střediska nové strany | ||

| b | Jak se vzbouřili roku 1912 veteráni v Rokycanech | Jaroslav Hašek | 27.2.1912 |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| d | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| e | 18.12.1905 | ||

| f | Příjmení: 'Koťátko', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| g | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních Sv. 2 | 1907 |

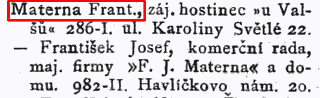

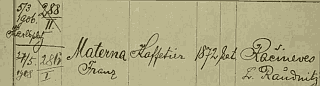

| Einjährigfreiwilliger Materna, František |  | ||||

| ||||||

, 1910

, 1851-1914

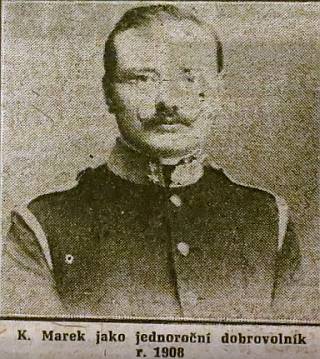

Materna was a one-year volunteer and an acquaintance of Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek. The latter mistook Materna for an artillery officer, knocked this lieutenant's cap off as a friendly gist, but this proved a costly mistake. He was now sharing a cell with Švejk. Moreover the episode led to Marek's expulsion from the reserve officer's school.

Background

A certain František Materna was owner of U Valšů (address book from 1910) and hence a person Jaroslav Hašek surely knew, and might thus have served as an inspiration. Whether or not this Materna was a one-year volunteer and served in Budějovice in 1915 has not yet been established but is very unlikely. According to police registers the landlord at U Valšů was born in 1872[c] and was thus too old to have been called up this early in the war. His Heimatrecht was in Račiněves north of Prague so he would not be expected to serve with any of the units garrisoned in South Bohemia. The records also revealed that he managed U Valšů from 1908 and that before that he was landlord at a pub at Karlovo námměstí, an area that Hašek frequented a lot, further strenghtening the hypothesis that Hašek knew him.

Moreover four person with this combination of names and surnames were listed in the addressbook for Prague in 1910 so there is no base for any firm conclusion. Materna is anyway probably yet another example of Hašek merely borrowing a name.

The surname in itself is fairly widespread but is rare in the recruitment area of IR91[a]. Still that in itself might not mean much as one-year volunteers could to a degree choose in which unit they wanted to serve. In Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 three Materna are registered in the loss list[b], they were all Gefreiter and might have been one year volunteers. None of them however bore the first name František.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Stalo se to tak, že ten poručík od dělostřelectva stál v noci pod podloubím a patrně čekal na nějakou prostitutku. Byl obrácen k němu zády a jednoročnímu dobrovolníkovi připadal, jako by to byl jeho jeden známý jednoročák, Materna František.

Literature

| a | Příjmení: 'materna', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| b | Seznamy ztrát - 91. pěší pluk | 2021 | |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 |

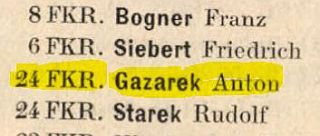

| Leutnant Anton |  | |||

| |||||

, 1916

Anton was the artillery officer that Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek knocked the cap off at Budějovické náměstí because he thought the officer was his friend Einjährigfreiwilliger Materna.

Background

Because Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in The Good Soldier Švejk is assigned details and events that to a degree hail from Hašek one can easily imagine that the author was involved in some incident with an artillery officer. In this case he would have been from Feldkanonenregiment Nr. 24 who were garrisoned in Budějovice. According to Schematismus there was in 1914 one single person with first name Anton amongst the officers: Fähnrich Anton Gaksch[a]. In Rangliste from 1916 he is no longer listed, and the reason seems to be that he was killed in action in the meantime[c]. On the other hand a Leutnant Anton Gazarek had joined the regiment, until 1 June 1916 Fähnrich[b].

Thus none of them had the rank of the officer that Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek clashed with and the first was even dead when Hašek enlisted with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in Budějovice on 17 February 1915. It is therefore tempting to suggest that the name Anton and his rank were picked more or less at random.

Incident on the tramway

Another version of the story appeared in a newspaper article in 1963[d]. According to this narrative the episode happened in the tramway and involved an unidentified high-ranking officer. The officer had the tramway stop, called a patrol and Hašek was arrested on the spot.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Napohlavkoval omylem jednomu poručíkovi od dělostřelectva v noci na náměstí v podloubí v opilém stavu.

[II.2] Může být,“ připouštěl jednoroční dobrovolník, „že při té tahanici padlo pár pohlavků, ale to myslím nic na věci nemění, poněvadž je to vyložený omyl. On sám přiznává, že jsem řekl: ,Servus, Franci’ a jeho křestní jméno je Anton. To je úplně jasné. Mně snad může škodit jenom to, že jsem utekl z nemocnice, a jestli to praskne s tím ,krankenbuchem’...

| a | Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 810) | 1914 | |

| b | Ranglisten des Kaiserlich und Königlichen Heeres (s. 695) | 1916 | |

| c | Vor dem Feinde gefallenen | 4.2.1915 | |

| d | Pátrání po stopách Haškovy českobudějovické anabáze | Vladimír Michal | 20.10.1963 |

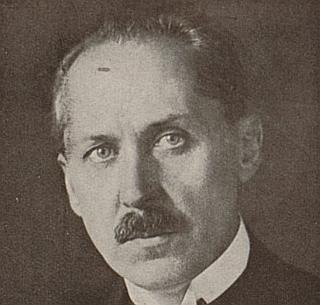

| Doctor Masák |  | ||||

| ||||||

MUDR. Jan Masák

Kulturní adresář ČSR, 1936

Masák was a doktor from Žižkov, brother-in-law of Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek. The doctor helped him prolong his stay at Budějovická nemocnice.

Background

Any obvious inspiration for this medic has not been identified. Hašek's chief doctor at the hospital in Budějovice was Peterka, he was not Žižkov, nor was he Hašek's brother-in-law. It is claimed that Peterka was sympathetic to Hašek, that he turned a blind eye to his disappearances from the hospital, and that he did his best to prolong the hospitalisation. It was Peterka who signed the application for superarbitration on behalf of Hašek 8 April 1915.

MUDR. Masák