Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people/animals that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2008) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others.

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are given in tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

II. At the front |

| |

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal | |||

| Krakonoš |  | |||

| |||||

From one of the many books about Krakonoš.

Václav Špáček,1883

Krakonoš is mentioned when the author describes Offiziersdiener Baloun, who with his huge frame and long beard resembles Krakonoš.

Background

Krakonoš is a German/Czech/Polish folklore mountain spirit of the Krkonoše mountain range (Riesengebirge), subject of many legends in the region. Görlitz and Vysoké nad Jizerou both have museums dedicated to this figure. He also appeared in numerous books and operas from the 19th century. Later he also became a theme for movies.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Před ním stál účetní šikovatel Vaněk, který zde sestavoval listiny k výplatě žoldu, vedl účty kuchyně pro mužstvo, byl finančním ministrem celé roty a trávil tu celý boží den, zde též spal. U dveří stál tlustý pěšák, zarostlý vousy jako Krakonoš. To byl Baloun, nový sluha nadporučíka, v civilu mlynář někde u Českého Krumlova.

Also written:RübezahldeLiczyrzepapl

Literature

| Offiziersdiener Baloun |  | ||||

| ||||||

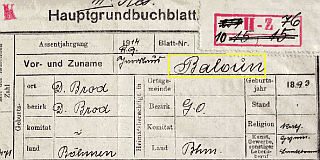

,6.4.1924

Jaroslav Baloun, 1893 - ?

© VÚA

Baloun is mentioned 191 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Baloun becomes the new officer's servant for Oberleutnant Lukáš when Oberst Schröder promotes Švejk to messenger at 11. Marschkompanie. He is part of the story the whole journey from Királyhida to the front, and figures regularly from now on. He is a huge man, incredibly gluttonous and all he can think of is food. Apart from this, he is portrayed as rather stupid. By profession, he is a miller, is married with three children and he often bobbled up the food of his family. Baloun is from the area around Krumlov.

He had also been on a pilgrimage to Klokoty, a fair distance to walk from Krumlov (appx. 85 km), particulalry with a wife and three children.

Background

Baloun has no clearly identifiable model from real life, but at least his gluttony may have been derived from the author himself, who at the time when he wrote this part of the novel put on a lot of weight. Jaroslav Hašek was known as a gourmet, something which is reflected in the many descriptions of food throughout the novel. According to Josef Lada he was also a very good cook.

There are several people with the name Baloun that the author might have met during his life, and could at least have lent their name (and even some personal traits) to the gluttonous miller from Krumlovsko.

Baloun is quite a common surname, and is particularly frequent in Humpolecko [b]. This was an area that Hašek knew well when he wrote this part of The Good Soldier Švejk in 1922. At the time he lived at Lipnice, only 11 km away.

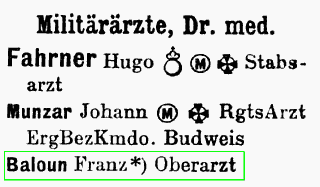

Head doctor Baloun

One of them was František Baloun, regimental doctor at Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. He is listed in the regiment's ranks in 1914, 1916 og 1917 so would most likely also had served IR. 91 also in 1915. It has however not been established whether he served with the regiment at the same time as Hašek. At the outbreak of war he was associated with the detached 1st battalion in Dalmatia, and if this was the case also in 1915 the two probably never met.

The young one-year volunteer

A more obvious candidate is one-year volunteer Jaroslav Baloun who was transferred from IR73 to IR. 91, 2. Ersatzkompanie on 1 April 1915, during the same time Jaroslav Hašek served at Ersatzbataillon IR. 91. It is very likely that the author knew about this Baloun as both were garrisoned in Budějovice. Baloun was in the spring of 1915 promoted to Kadett and fought with the regiment at Sokal where he was wounded on 27 June 1915.

That said it was probably only the name that served as an inspiration. The one-year volunteer was tall for the time (176 cm) but no miller. He was born in Německý Brod (since 1945 Havlíčkův Brod) and as a 22 year old in 1915 he surely didn't have three children.

The miller by Netolice

A certain Jindřich Baloun ran a mill by Netolice around 1930[a]. Hypothetically Jaroslav Hašek may have met him during a four-day "escape" from Budějovice in 1915, when he according to Radko Pytlík visited the area.

Hotel Neptun

Another possible link between Jaroslav Hašek and some Baloun is Hotel Neptun where the author lived for a few weeks after his return from to Prague from Russia 19 December 1920. A certain Josef Baloun managed this hotel in 1924, and may have done so also in 1921.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] U dveří stál tlustý pěšák, zarostlý vousy jako Krakonoš. To byl Baloun, nový sluha nadporučíka, v civilu mlynář někde u Českého Krumlova. „Vybral jste mně opravdu znamenitého pucfleka,“ mluvil nadporučík Lukáš k účetnímu šikovateli, „děkuji vám srdečné za to milé překvapení. První den si ho pošlu pro oběd do oficírsmináže, a on mně ho půl sežere.“

Sources: VÚA, Jan Ciglbauer, Radko Pytlík

Literature

| a | Záhadný Dub a Baloun | Jan Ciglbauer | 10.10.2017 |

| b | Příjmení: 'Baloun', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 |

| Korporal Weidenhofer |  | ||||

| ||||||

,12.6.1907

Národní listy,21.8.1908

Weidenhofer was a junior officer who was entrusted with tying up Offiziersdiener Baloun in the kitchen courtyard in Brucker Lager as punishment for having eaten the lunch of Oberleutnant Lukáš.

Background

Seemingly only a single Weidenhofer is recorded in Verlustliste throughout the war. That someone carrying this surname would have served with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 together with Hašek is thus practically ruled out. In modern Czechia the name is not found at all[a].

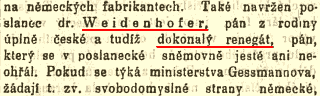

A renegade politician

One person that Hašek almost certainly was aware of was the German-National politician Emanuel Weidenhoffer (1874-1939). The name was also spelt Weidenhofer and often appeared in newspaper columns, particularly during the years 1907-1911 when he was a deputy in Reichsrat. Weidenhofer's anti-Czech attitudes were well known and Venkov, České slovo and some others labelled him a "renegade". Several of these papers claimed that he was born into a Czech family, and correctly so[b]. Weidenhofer was born in Napajedla in Moravia and in the church records he is entered as Emanuel František Jaroslav Karel Weidenhoffer[d].

In Prague II.

In Prague three Weidenhofer/Weidenhöfer were entered in the residence register and all in an area in Nové město that Hašek frequented[c]. Obviously, this is too little to draw any conclusion, but it can't be ruled out that Hašek borrowed the name from one of them.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] "Sie Rechnungsfeldwebl,“ obrátil se na Vaňka, „odveďte ho ke kaprálovi Weidenhoferovi, ať ho pěkně uváže na dvoře u kuchyně na dvě hodiny, až budou dnes večer rozdávat guláš. Ať ho uváže pěkně vysoko, aby jen tak se držel na špičkách a viděl, jak se v kotli ten guláš vaří.

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák

Literature

- Dr. Emanuel Weidenhoffer

- Gegen die Tschechifisierung Niederösterreichs23.6.1909

- K situaci21.8.1908

- K intervenci u bar. Bienertha4.9.1909

- Nový útok na české školství Dol. Rakousich23.9.1909

| a | Příjmení: 'Weidenhofer', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| b | Renegát Dr. Weidenhofer | 14.10.1909 | |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 | |

| d | Matrika narozených (Napajedla) |

| Stabsfeldwebel Hegner |  | |||

| |||||

Edvard Hegner was a person that Hašek almost certainly knew.

Density of the surname Hegner today.

Forebears.io,2012 - 2022

Hegner is mentioned 3 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Hegner was a staff sergeant who had served with Hauptmann Ságner in Serbia at the beginning of the war and had related to Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk how incompetently Ságner had acted at the border with Montenegro. Vaněk now relates this to Oberleutnant Lukáš just as the latter gets to know that Ságner has been promoted to battalion commander ahead of the former.

Background

As with Korporal Weidenhofer this is surely also a surname that Hašek more or less picked at random. In Schematismus no-one with this name is listed after 1862[a] and one has not identified any Hegner that can be associated with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In Czechia around 88 are resident today[b] and none from the recruitment district of IR. 91. Worldwide almost 3,800 bear the surname Hegner. The name is most common in Switzerland and Germany.

Editor Hegner

Still, a person existed who Hašek may have borrowed the name from. In Vinohrady lived and editor Edvard Hegner (1876-1929) and the writer and journalist Hašek was surely aware of him and most probably also knew him. Hegner wrote satires, other prose and theatre plays and contributed to several of the publications that Jaroslav Hašek also wrote for. Whether Hašek actually had Hegner in mind when he wrote this sequence of The Good Soldier Švejk is impossible to know but in such a case it could only have been "name-borrowing". Hašek often borrowed names and assigned them to one of his literary creations who might have little or nothing to do with the real-life person who bore the name. Prime examples are Břetislav Ludvík and not the least Švejk himself.

Sagner i Serbia

Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk's information can in no way be linked to Čeněk Sagner, the "model" of Hauptmann Ságner. Sagner did fight in Serbia but this was in the north, by Drina, and thereafter by Kolubara where he was injured. He was never posted at the front against Montenegro where the 1st battalion of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 operated at the start of the war.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „A víte, pane obrlajtnant,“ řekl, důvěrně mrkaje, „že se má stát pan hejtman Ságner batalionskomandantem našeho maršbatalionu? Napřed, jak říkal štábsfeldvébl Hegner, se myslelo, že vy budete, poněvadž jste nejstarší důstojník u nás, batalionskomandantem, a potom prý přišlo od divise na brigádu, že je jmenován pan hejtman Ságner.“

[II.5] „Já z toho nemám moc velkou radost,“ důvěrně se ozval účetní šikovatel, „vypravoval štábsfeldvébl Hegner, že pan hejtman Ságner v Srbsku na počátku války chtěl někde u Černé Hory v horách se vyznamenat a hnal jednu kumpačku svého baťáčku za druhou na mašíngevéry do srbských štelungů, ačkoliv to byla úplně zbytečná věc a infanterie tam byla starýho kozla co platná, poněvadž Srby odtamtud s těch skal mohla dostat jen artilerie.

[II.5] Vypravoval nedávno štábsfeldvébl Hegner, že příliš neladíte s panem hejtmanem Ságnerem a že on právě pošle naši 11. kumpačku první do gefechtu na ta nejhroznější místa.

Literature

- Hegner name meaning2024

- Hegner Surname2012 - 2022

| a | Militärschematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthumes | 1860 | |

| b | Příjmení: 'Hegner', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| c | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 |

| Mr. Kokoška, Ferdinand |  | |||

| *31.5.1846 Praha - †16.2.1906 Praha | |||||

| |||||

Adresař města Turnova,1892

Kološka and the young Hašek (Josef Lada)

,3.12.1904

Kokoška is mentioned 5 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Kokoška owned a chemist's store in Na Perštýně when Švejk was an apprentice there. This information is revealed when Švejk tells Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk about this experiences in this profession. Švejk accidentally set fire to a barrel of petrol, an accident that led to his dismissal. He also learnt how to prepare cow-fodder, the theme of most of the anecdote.)

This Kokoška is not identical to the Ferdinand Kokoška at the start of the novel, who collects dog turds (although the names of both men no doubt have the same origin).

Background

Kokoška was the proprietor of drogerie Kokoška at the corner of Na Perštýně and Martinská ulice where Hašek briefly worked as an apprentice in 1898. It has been verified that the pharmacy existed from 1890 until 1906 (Kokoška died that year). A picture of the shop from 1905 shows the name in the German version Kokoschka, a name used in most adverts and address books. Otherwise, population registers reveal that Kokoška was born in Prague, was married to Anna (born Milnerová) and that the couple had one daughter, also called Anna.

Police registers show that Kokoška was part owner of the company Ott. This is surely due to the fact his mother-in-law was Kateřina Ott, and that he may have inherited the part of it may even have been a marriage endowment. The firm Ott manufactured chemicals, poisonous substances, and other items associated with chemists.

Kokoška is pivotal in the stories From the old pharmacy where he is half-heartedly re-named Kološka. He is described as a very short elderly man with a large moustache[a]. Václav Menger provides additional information in his book Jaroslav Hašek doma (1935) and in two articles in 1933. According to Václav Menger, the-15 year old Hašek was dismissed after having painted a beard and glasses on an Alpine cow to make it resemble the boss[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Já jsem se taky učil materialistou,“ řekl Švejk, „u nějakýho pana Kokošky na Perštýně v Praze. To byl náramnej podivín, a když jsem mu jednou vomylem ve sklepě zapálil sud benzinu a von vyhořel, tak mne vyhnal a gremium mne už nikde nepřijalo, takže jsem se kvůli pitomýmu sudu benzinu nemoh doučit. Vyrábíte také koření pro krávy?“

[II.5] „U nás se vyrábělo koření pro krávy se svěcenými obrázky. Von byl náš pan šéf Kokoška náramně nábožnej člověk a dočetl se jednou, že svatej Pelegrinus pomáhal při nafouknutí dobytka.

[II.5] Tak si večer zavolal náš starej Kokoška pana Tauchena a řek mu, aby do rána sestavil nějakou modlitbičku na ten obrázek a na to koření, až přijde v deset hodin do krámu, že už to musí bejt hotový, aby to šlo do tiskárny, že už krávy čekají na tu modlitbičku.

[II.5] Kokoškovo koření, jež ho zbaví trápení...

[II.5] Potom, když přišel pan Kokoška, pan Tauchen šel s ním do komptoiru, a když vyšel ven, ukazoval nám dva zlatníky, ne jeden, jak měl slíbeno, a chtěl se s panem Ferdinandem rozdělit napolovic.

Sources: Václav Menger

Also written:Kokoschkade

Literature

- Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920)

- Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství1851 - 1914

- Ferdinand Kokoschka1892

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních1907

- Ferdinand Kokoška & spol.

- Z droguerieJaroslav Hašek24.3.1904

- Sterbefall18.2.1906

- Hašek inteligentním praktikantem2.7.1933

| a | Ze staré drogerie | Jaroslav Hašek | 1909 - 1910 |

| b | Hašek si loučí s drogerií | 9.7.1933 |

| Saint Peregrinus |  | |||

| |||||

Břetislav Hůla,1951

Saint Peregrinus is mentioned 8 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Saint Peregrinus had his named invoked by Mr. Kokoška when sanctifying the herbs for bloated cows, all revealed when Švejk tells Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk about his time as a chemist's apprentice.

Background

Saint Peregrinus may be one of seven different saints with the name Pelegrinus or Peregrinus[a], mostly martyrs from early Christianity. Břetislav Hůla concludes that Švejk refers to a martyr who was beatified on 27 April[c].

A contrasting claim is that the saint in question is Peregrine Laziosi, a patron saint for pregnant women and women giving birth[b].

Inconclusive

Whatever Peregrinus one prefers: none of the seven candidates appear to have any connection to cattle or other livestock. Nor does the date 27 April provide further clues. Laziosi is however more famous than the rest would thus be a "best guess".

Antonín Měšťan

... während der Hl. Peregrinus (Pellegrin) in Wirklichkeit für die katolische Kirche der Patron der Gebärenden, der Wöchnerinnen und der Lohnkutscher ist.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „U nás se vyrábělo koření pro krávy se svěcenými obrázky. Von byl náš pan šéf Kokoška náramně nábožnej člověk a dočetl se jednou, že svatej Pelegrinus pomáhal při nafouknutí dobytka.

Also written:Svatý Peregrinuscz

| a | Saints A to Z: P | ||

| b | Realien und Pseudorealien in Hašeks "Švejk" | 1983 | |

| c | Vysvětlivky | 1951 |

| Mr. Tauchen |  | ||||

| ||||||

Václav Menger

Lidové noviny,2.7.1933

Václav Menger,1935

Tauchen is mentioned 8 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Tauchen is mentioned when Švejk tells Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk about his time as a chemist's apprentice. Tauchen was a shop-assistant at drogerie Kokoška, who was given the task of writing religious poems to go with the cow-herbs.

NB! Not to be confused with one Mr. Tauchen who had a similar position at firma Polák.

Background

The author's apprenticeship at drogerie Kokoška in 1898 and/or 1899 inspired a series of eight stories that were published in Veselá Praha[a]. Already here Tauchen appears but with his name slightly twisted but still easily recognizable (Tauben). It is almost certain that some Tauchen (or similarly named) worked for Kokoška but it has to this day not been possible to establish his identity.

Menger

In two newspaper articles[b][c] Václav Menger provides extensive details about Hašek's time as an apprentice at drogerie Kokoška, based partly on what Hašek himself had told him but he also consulted still people who had worked at the chemist's. Menger reveals that the names of the participants in the stories were still alive so Hašek twisted their names. Tauben is thus not the real name of the person that Hašek made fun of in the stories. "Tauben" was like Hašek an apprentice but older than the budding author. In the beginning teh two got on well but after the latter had the story "Žere taký citrony?" (Does he also eat lemons?) published in Národní listy Tauben became jealous and started to treat his younger colleague with contempt. Hašek took revenge by setting in motion a rumour that eventually caused Tauben to leave his post. Otherwise, Menger informs that Tauben lived in Vyšehrad and that he liked to boast about his parent's wealth.

There is ample reason to be sceptical of Václav Menger's account, particularly because Hašek himself is partly his source. Thus one must at least expect some exaggeration or even inventions. That Hašek had stories published as early as 1898 or 1899 also seems improbable and has never been verified.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] A potom jsme je přikládali do balíčků toho našeho koření pro krávy. Krávě se to koření namíchalo do teplý vody, dalo se jí napít z dřezu a přitom se dobytku předčítala modlitbička k sv. Pelegrinovi, kterou složil pan Tauchen, náš příručí. To když byly ty obrázky sv. Pelegrina vytištěny, tak ještě na druhou stranu bylo potřeba natisknout nějakou modlitbičku.

Literature

| a | Ze staré drogerie | Jaroslav Hašek | 1909 - 1910 |

| b | Hašek inteligentním praktikantem | Václav Menger | 2.7.1933 |

| c | Hašek si loučí s drogerií | Václav Menger | 9.7.1933 |

| Servant Ferdinand |  | |||

| |||||

Ferdinand is mentioned 6 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Ferdinand was, like Mr. Tauchen , a servant at drogerie Kokoška, and had to help Tauchen write poems to go with the cow-herbs. This led to a row about the origin av authorship, but Švejk never managed to finish the story as Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk received a phone call.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Dokonce zapomněl, jak se ten svatej do toho koření pro krávy jmenuje. Tak ho vytrh z bídy náš sluha Ferdinand. Ten uměl všechno. Když jsme sušili na půdě heřmánkový thé, tak si tam vždycky vlez, zul si boty a naučil nás, že se přestanou nohy potit.

[II.5] A než jsem pivo přines, tak už náš sluha Ferdinand byl s tím napolovic hotov a už předčítal:...

[II.5] Potom, když přišel pan Kokoška, pan Tauchen šel s ním do komptoiru, a když vyšel ven, ukazoval nám dva zlatníky, ne jeden, jak měl slíbeno, a chtěl se s panem Ferdinandem rozdělit napolovic. Ale sluhu Ferdinanda, když viděl ty dva zlatníky, chyt najednou mamon. Že prej ne, buď všechno, anebo nic. Tak tedy pan Tauchen mu nedal nic a nechal si ty dvě zlatky pro sebe, vzal mě vedle do magacínu, dal mně pohlavek a řek, že dostanu takových pohlavků sto, když se někde vopovážím říct, že on to nesestavoval a nespisoval, i kdyby si šel Ferdinand stěžovat k našemu starýmu, že musím říct, že sluha Ferdinand je lhář. Musel jsem mu to vodpřísáhnout před nějakým plucarem s estragonovým voctem.

| a | Hašek inteligentním praktikantem | Václav Menger | 2.7.1933 |

| b | Ze staré drogerie | Jaroslav Hašek | 1909 - 1910 |

| Ordonnanz Braun |  | |||

| |||||

Braun was the orderly of the 12th march company, and Švejk had an unrewarding phone conversation with him in his first task as orderly of the 11th march company.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Vaněk? Ten šel do regimentskanceláře. Kdo je u telefonu? Ordonanc od 11. marškumpanie. Kdo je tam? Ordonanc od 12. maršky? Servus, kolego. Jak se jmenuji? Švejk. A ty? Braun. Nemáš příbuznýho nějakýho Brauna v Pobřežní třídě v Karlíně, kloboučníka? Že nemáš, že ho neznáš...

| Hatter Braun |  | |||

| |||||

Braun was a hatter from Pobřežní třída in Karlín who was mentioned in the conversation between orderly Ordonnanz Braun and Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Vaněk? Ten šel do regimentskanceláře. Kdo je u telefonu? Ordonanc od 11. marškumpanie. Kdo je tam? Ordonanc od 12. maršky? Servus, kolego. Jak se jmenuji? Švejk. A ty? Braun. Nemáš příbuznýho nějakýho Brauna v Pobřežní třídě v Karlíně, kloboučníka? Že nemáš, že ho neznáš...

| Zugsführer Fuchs |  | |||

| |||||

Zugsführer Fuchs to the left.

,6.4.1924

Fuchs was a squad leader (četař) who was ordered by Oberleutnant Lukáš to fetch tins from the stores. It was Švejk who conveyed the order. The tins turned out to be imaginary as much else in the k.u.k armed forces.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Četař Fuchs byl tak překvapen, že vypravil ze sebe jen: „Cože?“ „Žádný ,cože’,“ odpověděl Švejk, „já jsem ordonanc jedenáctý marškumpanie a právě před chvílí jsem mluvil po telefonu s panem obrlajtnantem Lukášem. A ten řek: ,Laufšrit s deseti muži k magacínu.’ Jestli nepůjdete, pane cuksfíra Fuchse, tak ihned jdu nazpátek k telefonu. Pan obrlajtnant si výhradně přeje, aby vy jste šel. Je to zbytečný vůbec vo tom mluvit. ,Telefonní rozhovor,’ říká pan nadporučík Lukáš, ,musí bejt krátký, jasný.

| Korporal Blažek |  | ||||

| ||||||

Korporal Blažek in the middle.

,6.4.1924

Blažek is a corporal who just about gets a word in after Švejk has given Zugsführer Fuchs orders to draw a supply of tins from stores.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Hned budu s deseti maníkama u magacínu,“ ozval se od baráku četař Fuchs, a Švejk nepromluviv již ani slova odcházel ze skupiny šarží, které byly stejně překvapeny jako četař Fuchs. „Už to začíná,“ řekl malý desátník Blažek, „budeme pakovat.“

| Leutnant Přenosil |  | |||

| |||||

Přenosil was a lieutenant that Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk talked about. He was in a previous march company that Vaněk had travelled to the front with.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Ale u nás byl kumpaniekomandantem lajtnant Přenosil, velký fešák, a ten nám řek: ,Nespěchejte, hoši,’ a šlo to jako na másle. Dvě hodiny před odjezdem vlaku jsme teprve začli pakovat. Uděláte dobře, když se taky posadíte...“

| Lucie |  | |||

| |||||

Lucie is mentioned in the drunken drivel of the staff sergeant who got a bribe from a farmer from Pardubice. Švejk and Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk witnessed the wooly utterings.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Ten se udělal úplně pro sebe a blábolil, hladě čtvrtku vína, prapodivné věci beze vší souvislosti česky i německy: „Mnohokrát prošel jsem touto vesnicí a neměl jsem ani potuchy o tom, že je na světě. In einem halben Jahre habe ich meine Staatsprüfung hinter mir und meinen Doktor gemacht. Stal se ze mne starý mrzák, děkuji vám, Lucie. Erscheinen sie in schön ausgestatteten Bänden - snad je tu někdo mezi vámi, jenž se na to pamatuje.“

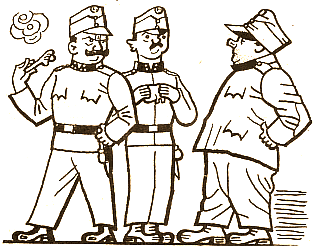

| Cook Jurajda |  | ||||

| ||||||

Jurajda is mentioned 44 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Jurajda is a cook in the officer's mess in Bruck, later in Švejk's march company. He takes part in the journey from Bruck an der Leitha - Királyhida all the way to the novel's end in Klimontów.

Jurajda is an occultist, in civilian life he published an occultist magazine and the book series Mysteries of Life and Death. He regularly chips in with thoughts on karma, transmigration of souls, and a number of questions of existential significance. These range from our earthly existence to the life beyond.

Apart from this, he is a good cook and very popular amongst the officers. Still, Oberst Schröder dispatched him to the front because he was slightly unlucky with the meal for the officer's farewell party in Bruck.

Background

Any obvious "model" for Hašek's company cook has not been identified. There is no Jurajda in the records of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91, be it in Verlustliste, other army papers or in the recollections of Hašek's contemporaries in IR91. The cook in Hašek's 11. Kompanie in 1915 was some Perníček and he may also have served with Hašek in XII. Marschbataillon. Moreover it should be noted that the surname Jurajda is extremely rare in the recruitment district of IR91[d] and this was surely the case also in 1915.

Kamil Jurajda

Augustin Knesl, , 1983

Augustin Knesl informs that Hašek knew a certain Kamil Jurajda from Rožnov pod Radhoštěm in Moravia and claims that this person is the model for the occultist cook[e]. Jurajda was born in 1883 and graduated as an agronomic at the technical college at Karlovo náměstí. Hašek knew many students from this institution and Knesl arrived at the conclusion that the author of The Good Soldier Švejk borrowed names for several of his literary characters from his circle of acquaintances here. Knesl claims that Jurajda was very religious and in addition an occultist but considering that Knesl tended to interpret fiction from The Good Soldier Švejk as facts there is good reason to view his claim with scepticism. Still, there is no doubt that Kamil Jurajda was born in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm in 1883[f]. From the autumn of 1912 he lived in Vinohrady. During World War I Jurajda served as a Leutnant with k.k. Landsturm in the hinterland and obviously had no connection to Infanterieregiment Nr. 91.

The occultist Adamíra

, 1934-1936

A more likely inspiration for Jurajda is Josef Alois Adamíra (1877-1953), a chemist who was employed at the laboratory of Zemědelská rada (The Agricultural Council)[b]. Important in the context of The Good Soldier Švejk is however that he was a prominent occultist[c]. Jaroslav Hašek lived in the flat of Adamíra in Havlíčkova třída at Vinohrady for a period from 29 July 1912[a] and one could easily imagine that Hašek picked up knowledge about occultism from him and that he later may have made use of this when he created his character Jurajda.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Kuchař Jurajda se dal do filosofování, což fakticky odpovídalo jeho bývalému zaměstnání. Vydával totiž do vojny okultistický časopis a knihovnu „Záhady života a smrti“. Na vojně ulil se k důstojnické kuchyni regimentu a velice často připálil nějakou pečeni, když se zabral do čtení překladů staroindických suter Pragnâ-Paramitâ (Zjevená moudrost). Plukovník Schröder měl ho rád jako zvláštnost u regimentu, neboť která důstojnická kuchyně mohla se pochlubit kuchařem okultistou, který nazíraje do záhad života a smrti, překvapil všechny takovou dobrou svíčkovou nebo s takovým ragout, že pod Komárovem smrtelně raněný poručík Dufek volal stále po Jurajdovi.

| a | Haškovi v Praze | ||

| b | Adresář města Král. Vinohradů | 1912 | |

| c | Adamíra Josef Alois | 1934-1936 | |

| d | Příjmení: 'Jurajda', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| e | Švejk a ti druzí | Augustin Knesl | 1983 |

| f | Pobytové přihlášky pražského policejního ředitelství | 1851 - 1914 |

| Leutnant Dufek |  | |||

| |||||

Dufek was a lieutenant who was mortally wounded by Komarów and called out for cook Jurajda at the moment when he stepped into the existence beyond.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Plukovník Schröder měl ho rád jako zvláštnost u regimentu, neboť která důstojnická kuchyně mohla se pochlubit kuchařem okultistou, který nazíraje do záhad života a smrti, překvapil všechny takovou dobrou svíčkovou nebo s takovým ragout, že pod Komárovem smrtelně raněný poručík Dufek volal stále po Jurajdovi.

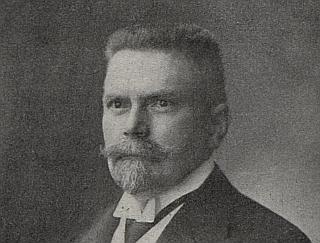

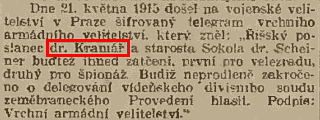

| Kramář, Karel |  | |||

| *27.12.1860 Vysoké nad Jizerou - †26.5.1937 Praha | |||||

| |||||

,20.7.1917

,15.3.1930

Dr. Karl Kramarsch, the true instigator of the world war.

Friedrich Wichtl,1918

Kramář (in the germanised variation Kramarsch) is mentioned in Oberst Schröder's ruminations about the lack of loyalty amongst Czech soldiers. This happened as the officers are having a Besprechung over the imminent transfer to the front.

Background

Kramář was a Czech politician and long time leader of Mladočeši who was arrested on 21 May 1915 and sentenced to death for high treason in December that year. The sentence was later converted to 20 years imprisonment, and he was released under the general amnesty given by the new emperor Karl I. in 1917.

Kramář was a member of Reichsrat from 1891 and the Czechoslovak parliament from 1920 until his death in 1937. He was in 1918 to become the first prime minister of Czechoslovakia but his cabinet resigned the following year. Kramář was known as a panslavist and his wife was Russian.

A spectacular conspiracy theory

In 1918 the German-National Reichsrat deputy Friedrich Wichtl (1872-1921) published a book where he concluded that "Dr. Karl Kramarsch" was "the real instigator of the world war"[a].

In this perspective it should be noted that Wichtl also was a propagator of the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory, a central pillar of Nazism (and still floating around today).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Rozhovořil se o poměru důstojníků k mužstvu, mužstva k šaržím, o přebíhání na frontách k nepříteli a o politických událostech a o tom, že 50 procent českých vojáků je „politisch verdächtig“. „Jawohl, meine Herren, der Kramarsch, Scheiner und Klófatsch.“ Většina důstojníků si přitom myslela, kdy už přestane dědek cancat, ale plukovník Schröder žvanil dál o nových úkolech nových maršbatalionů, o padlých důstojnících pluku, o zeppelinech, španělských jezdcích, o přísaze.

Literature

- Proces Dra Kramáře a jeho přátel1918

- Karel Kramář1930

- Town marks 150th anniversary of birth of Czechoslovakia’s first prime ministerJan Velinger

- Der Führer der Jungtschechen…29.5.1915

- Kapitoly z činnosti Maffie15.3.1930

- Zatčení dr. K. Kramáře dne 21.května 191529.12.1935

| a | Dr. Karl Kramarsch, der Anstifter des Weltkrieges | 1918 |

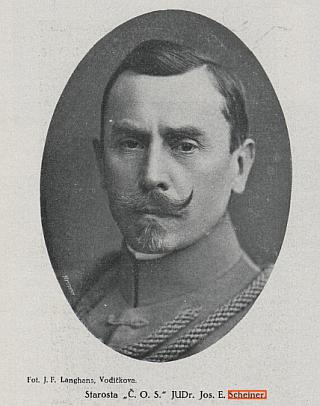

| Scheiner, Josef Eugen |  | |||

| *21.9.1861 Benešov - †11.1.1932 Praha | |||||

| |||||

, 28.11.1913

Adresář hl. m. Prahy 1910

Scheiner is mentioned in Oberst Schröder's ruminations about the loyalty of the Czechs. This happened as the officers are having a Besprechung over the imminent transfer to the front.

Background

Scheiner was a Czech politician, and like Kramář associated with the Czech domestic resistance movement during World War I, the so-called "Mafia". He was the long-time leader of Sokol, both the Czech and the international organisation (he founded the latter in 1908). He was also editor-in-chief of their monthly Sokol. On 21 May 1915 he was arrested and charged with espionage but was released later that year and allowed to return to Prague.

After the war he was for a period head of the Czechoslovak armed forces and also inspector general, but for the most part he dedicated the rest of his life to Sokol.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Rozhovořil se o poměru důstojníků k mužstvu, mužstva k šaržím, o přebíhání na frontách k nepříteli a o politických událostech a o tom, že 50 procent českých vojáků je „politisch verdächtig“. „Jawohl, meine Herren, der Kramarsch, Scheiner und Klófatsch.“ Většina důstojníků si přitom myslela, kdy už přestane dědek cancat, ale plukovník Schröder žvanil dál o nových úkolech nových maršbatalionů, o padlých důstojnících pluku, o zeppelinech, španělských jezdcích, o přísaze.

Literature

- Kapitoly z činnosti Maffie15.3.1920

- Dr. Josef Scheiner11.1.1932

| Klofáč, Václav Jaroslav |  | |||

| *21.9.1868 Německý Brod - †10.7.1942 Dobříkov | |||||

| |||||

, 20.7.1917

Klofáč is mentioned in Oberst Schröder's ruminations about the lack of loyalty amongst Czech soldiers. This happened as the officers are having a Besprechung over the march battalion's imminent transfer to the front.

Background

Klofáč was a Czech politician and journalist, member of Reichsrat, chairman of Česká strana národně sociální. He was arrested in September 1914 and sentenced for high treason as late as 1917. Later that year he was released, a result of a general amnesty issued by the new emperor Karl I. In Czechoslovakia he was minister of the interior from 1918 to 1920, and held the post of senator until 1938.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Rozhovořil se o poměru důstojníků k mužstvu, mužstva k šaržím, o přebíhání na frontách k nepříteli a o politických událostech a o tom, že 50 procent českých vojáků je „politisch verdächtig“. „Jawohl, meine Herren, der Kramarsch, Scheiner und Klófatsch.“ Většina důstojníků si přitom myslela, kdy už přestane dědek cancat, ale plukovník Schröder žvanil dál o nových úkolech nových maršbatalionů, o padlých důstojnících pluku, o zeppelinech, španělských jezdcích, o přísaze.

| Graf von Zeppelin, Ferdinand |  | |||

| *8.7.1838 Konstanz - †8.3.1917 Berlin | |||||

| |||||

,18.3.1917

,13.3.1917

Zeppelin is mentioned in a long speech by Oberst Schröder in the same breath as the tasks of march battalions, fallen officers, Spanish riders etc., albeit indirectly through the term "Zeppeliner" (air-ship).

Background

Zeppelin was a German officer and best known for the invention of the airship. Born into a wealthy and influential family in Konstanz, he graduated from the war academy in Ludwigsburg. He was present as an observer in the American Civil War and noted how balloons were used in the conflict. This no doubt inspired his famous future invention.

The first airship flight took place on 2 July 1900 over Lake Constance. Several more Zeppeliners were built over the next fourteen years, some of them for the armed forces.

Zeppeliners played a certain role in World War I, and were widely used (by Germany in particular) for bombing and reconnaissance. They eventually proved vulnerable due to their large target area. In the inter-war years they had a renaissance, but the Hindenburg disaster in 1937 effectively proved the end.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Většina důstojníků si přitom myslela, kdy už přestane dědek cancat, ale plukovník Schröder žvanil dál o nových úkolech nových maršbatalionů, o padlých důstojnících pluku, o zeppelinech, španělských jezdcích, o přísaze.

Literature

| Militarartz Šancler |  | |||

| |||||

Šancler was a military doctor who sat in Offizierskasino in Királyhida, reading aloud from a book on treatment of the wounded. Oberleutnant Lukáš was the only person present.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Nadporučík Lukáš seděl ještě zatím v důstojnickém kasině s vojenským lékařem Šanclerem, který sedě obkročmo na židli, tágem bil v pravidelných přestávkách o podlahu a přitom pronášel tyto věty za sebou: „Saracénský sultán Salah-Edin poprvé uznal neutralitu sanitního sboru. Má se pečovat o raněné na obou stranách.

| Sultan Saladin |  | |||

| *1137/38 Tikrit - †4.3.1193 Damaskus | |||||

| |||||

Saladin was a Saracen sultan who is said to have been the first to decree that wounded from both sides should get equal treatment. This is amongst the things that militarartz Šancler reads aloud to Oberleutnant Lukáš at Offizierkasino.

Background

Saladin was the leader of the muslim resistance against the Christian crusaders and was the one who finally repelled the intruders, capturing Jerusalem in 1187. Saladin was known for his good treatment of captured opponents, which has given him a good name even until today both in the Muslim and Christian world. He was of Kurdish descent, and by a twist of irony born in the same city as Saddam Hussein.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Nadporučík Lukáš seděl ještě zatím v důstojnickém kasině s vojenským lékařem Šanclerem, který sedě obkročmo na židli, tágem bil v pravidelných přestávkách o podlahu a přitom pronášel tyto věty za sebou: „Saracénský sultán Salah-Edin poprvé uznal neutralitu sanitního sboru. Má se pečovat o raněné na obou stranách.

Also written:Salah-EdinHašekṢalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūbar

| Anna Nána |  | |||

| |||||

Anna Nána features in one of Švejk's songs.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5]Mlynářovic ráno vstali, na dveřích napsáno měli: „Vaše dcera Anna Nána už není poctivá panna.“

| Gas worker Zátka |  | |||

| |||||

Zátka was employed at the gas station at Letná and his task was to lit and put out gas lamps. He had a lot of spare time between lighing the lamps and putting them out, and many pubs were found on his route. This could result in early morning utterances like: A cube is all an edge and angle, that’s why a cube is angular. This is Švejk's comparison to cook Jurajda's ideas on formation and non-being. See Plynární stanice Letna.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Co se mý osoby týká, pane rechnungsfeldvébl, když jsem to slyšel, co vy jste vo těch outvarech povídal, tak jsem si vzpomněl na nějakýho Zátku, plynárníka; von byl na plynární stanici na Letný a rozsvěcoval a zas zhasínal lampy.

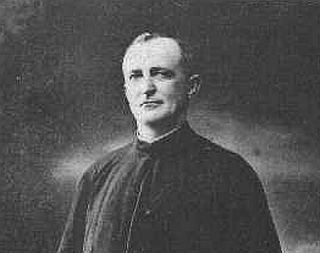

| Father Jemelka, Alois |  | ||||

| *27.3.1862 Kozlovice - †4.1.1917 Wien | ||||||

| ||||||

, 24.7.1912

Jemelka is mentioned in the same anecdote as gas worker Zátka where Jemelka's sermons at kostel svátého Ignáce are referred to.

Background

Jemelka was a Jesuit priest who had a post at kostel svátého Ignáce. He did, amongst other things, get involved in a debate on religion with professor Professor Masaryk and also wrote a book about it: Masarykův boj o náboženství.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] A potom,“ řekl Švejk tiše, „to s tím Zátkou po čase skončilo moc špatně. Dal se do Mariánský kongregace, chodil s nebeskýma kozama na kázání pátera Jemelky k svatýmu Ignáci na Karlovo náměstí a zapomenul jednou zhasnout, když byli misionáři na Karláku u svatýho Ignáce, plynový svítilny ve svým rayoně, takže tam hořel po ulicích plyn nepřetržitě po tři dny a noci.

Literature

| Major Blüher |  | |||

| |||||

,13.4.1924

Blüher was an officer from Švejk's national service who he related to Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk about. The major was of the opinion that an officer is the most perfect being on earth, and one of Švejk's comments didn't quite fit.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] To je velmi špatný,“ pokračoval Švejk, „když se najednou člověk začne plést do nějakýho filosofování, to vždycky smrdí delirium tremens. Před léty k nám přeložili od pětasedmdesátejch nějakýho majora Blühera. Ten vždy jednou za měsíc dal si nás zavolat a postavit do čtverce a rozjímal s námi, co je to vojenská vrchnost. Ten nepil nic jiného než slivovici. ,Každej oficír, vojáci,’ vykládal nám na dvoře v kasárnách, ,je sám vod sebe nejdokonalejší bytost, která má stokrát tolik rozumu jako vy všichni dohromady.

| Rekrut Pech |  | |||

| |||||

,13.4.1924

Pech was a recruit from Dolní Bousov, described by Švejk in conversation with Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk. He was locked up for giving such exact answers to Leutnant Moc and Major Rohell that these perceived it as sarcasm.

Background

Pech might have been a fictional but his answer was real enough: it is an almost literal quote from Ottův slovník naučný.

Ottův slovník naučný

Bousov Dolní, Bohousov, Boužov (něm. Unter-Bautzen), město t., s 267 d., 1936 obyv. čes. (1880), hejtm. Jičín, okr. Sobotka (5 km jihozáp.), býv. panství Kosť, farní chrám sv. Kateřiny, pův. ze XIV. stol. obnovený od hr. Václava Vratislava Netolického, škola, pošta, telegraf, stanice české obchodní dráhy, 6 výročních trhů, cukrovar, mlýn s pilou, zv. Červený, a samota Valcha.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] ,Vy rekruti zelení, zatracení,’ povídá k nim, ,vy se musíte naučit vodpovídat jasně, přesně a jako když bičem mrská. Tak to začnem. Odkud jste, Pechu?’ Pech byl inteligentní člověk a vodpověděl: ,Dolní Bousov, Unter Bautzen, 267 domů, 1936 obyvatelů českých, hejtmanství Jičín, okres Sobotka, bývalé panství Kosť, farní chrám svaté Kateřiny ze 14. století, obnovený hrabětem Václavem Vratislavem Netolickým, škola, pošta, telegraf, stanice české obchodní dráhy, cukrovar, mlýn s pilou, samota Valcha, šest výročních trhů.’

| Leutnant Moc |  | |||

| |||||

,13.4.1924

Moc was a lieutenant who in one of Švejk's anecdotes asked all the recruits where they were from. He then ordered Rekrut Pech to be excact in his answer when asked where he was from, and duly received a volley of encyclopaedic details about Dolní Bousov.

Background

This person may well have been fictional, but the answer he got was defintely from the real world. See Rekrut Pech.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Docela dobře řečeno,“ pravil Švejk. „Na to nikdy nezapomenu, jak zavřeli rekruta Pecha. Lajtnant od kumpanie byl nějakej Moc a ten si shromáždil rekruty a ptal se každýho, vodkud je.

| Major Rohell |  | |||

| |||||

Rohell was the officer who dealt with Rekrut Pech's complaint after Leutnant Moc had whacked him because his answer was too excact. Rohell then got Pech locked up at the asylum of the military hospital.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Batalionskomandantem byl major Rohell. ,Also, was gibst?’ otázal se Pecha a ten spustil: ,Poslušně hlásím, pane majore, že v Dolním Bousově je šest výročních trhů.’ Jak na něho major Rohell zařval, zadupal a hned ho dal odvést na magorku do vojenskýho špitálu, vod tý doby byl z Pecha nejhorší voják, samej trest.“

| Graf Netolický, Václav Vratislav |  | |||

| *1700 Přehořov - †? 1760 | |||||

| |||||

Netolický renovated, according to Rekrut Pech, the church in Dolní Bousov.

Background

Netolický probably refers to Václav Kazimír Graf Netolický z Eisenberka, Imperial Field Marshal and from 1759 lord of Kost.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] ,Dolní Bousov, Unter Bautzen, 267 domů, 1936 obyvatelů českých, hejtmanství Jičín, okres Sobotka, bývalé panství Kosť, farní chrám svaté Kateřiny ze 14. století, obnovený hrabětem Václavem Vratislavem Netolickým, škola, pošta, telegraf, stanice české obchodní dráhy, cukrovar, mlýn s pilou, samota Valcha, šest výročních trhů.’

| Infantryman Sylvanus |  | |||

| |||||

Sylvanus was an infantryman who in civilian life had been in and out of prison, but proved to be an efficient soldier. He was executed though, after getting caught robbing the dead. This is according to Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk in a conversation with Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Pamatuji se u osmé maršky na infanteristu Sylvanusa. Ten měl dřív trest za trestem, a jaké tresty. Neostýchal se ukrást kamarádovi poslední krejcar, a když přišel do gefechtu, tak první prostříhal drahthindernissy, zajmul tři chlapy a jednoho hned po cestě odstřelil, že prý mu nedůvěřoval.

| Fähnrich Pleschner |  | |||

| |||||

Pleschner was an junior officer who was involved in preparing for abmarsch from Királyhida. He also appears before Budapest where he gives Kadett Biegler cognac.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Co má dnes s manšaftem dělat fähnrich Pleschner? Vorbereitung zum Abmarsch. Účty? Přijdu podepsat po mináži. Nikoho nepouštějte do města. Do kantiny v lágru? Po mináži na hodinu... Zavolejte sem Švejka!

| Zugsführer Teveles |  | |||

| |||||

Rovnost, 15.4.1915

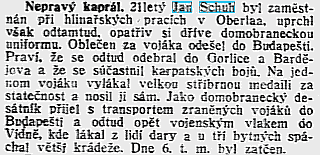

Teveles was a squad leader who was locked up in Királyhida after being caught with a war medal he had bought and with one-year volunteer stripes he had sewed on himself. This had happened during the retreat from Belgrade on 2 December 1914.

Background

A story with certain paralleles to the Teveles affair appeared in the newspapers in 1915. The 21 year old Jan Schuh had falsely pretended to be a corporal and had also aquired a war medal that wasn't his.

In this narrative the author mixes up dates and events. K.u.k. Heer pulled out of Belgrade 14 December 1914 but they had indeed entered the Serbian capital on the 2nd.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Potom byl ještě druhý případ. S jednoročním dobrovolníkem Markem dodán byl současně na hauptvachu od divisijního soudu falešný četař Teveles, který se nedávno objevil u regimentu, kam byl poslán z nemocnice v Záhřebě. Měl velkou stříbrnou medalii, odznaky jednoročního dobrovolníka a tři hvězdičky.

Literature

- Ein Kriegsschwindler13.4.1915

| Zwiebelfisch |  | |||

| |||||

Zwiebelfisch was the staff secretary who allowed a tom cat to enter the office. The cat then crapped all over the map of the battlefield.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Výslech byl krátký. Zjistilo se, že kocoura před čtrnácti dny přitáhl do kanceláře nejmladší písař Zwieblfisch. Po tomto zjištění sebral Zwiebelfisch svých pět švestek a starší písař ho odvedl na hauptvachu, kde bude tak dlouho sedět, až do dalšího rozkazu pana plukovníka.

| Gefreiter Peroutka |  | |||

| |||||

Peroutka was a lance corporal from the 13th march company who disappeared from the camp in Királyhida when the rumours about an imminent departure to the front started to spread. He was found at Zur weißen Rose in Bruck.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Potom tam ještě k nim strčili frajtra Peroutku od 13. marškumpanie, který, když se včera rozšířila pověst po lágru, že se jede na posici, se ztratil a byl ráno patrolou objeven „U bílé růže“ v Brucku. Vymlouval se, že chtěl před odjezdem prohlédnout známý skleník hraběte Harracha u Brucku a na zpáteční cestě že zabloudil, a teprve ráno celý unavený že dorazil k „Bílé růži“. (Zatím spal s Růženkou od „Bílé růže“.)

| Růženka |  | |||

| |||||

Růženka was a bar lady at Zur weißen Rose who Gefreiter Peroutka had slept with the night with before he got caught after trying to avoid departure to the front.

Background

Růženka appears to have had a real-life model. According to Bohumil Vlček she worked at a bar that was popular amongst Czech soldiers in Bruck: "U růže" (Zur Rose/At the Rose).

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Potom tam ještě k nim strčili frajtra Peroutku od 13. marškumpanie, který, když se včera rozšířila pověst po lágru, že se jede na posici, se ztratil a byl ráno patrolou objeven „U bílé růže“ v Brucku. Vymlouval se, že chtěl před odjezdem prohlédnout známý skleník hraběte Harracha u Brucku a na zpáteční cestě že zabloudil, a teprve ráno celý unavený že dorazil k „Bílé růži“. (Zatím spal s Růženkou od „Bílé růže“.)

Sources: Bohumil Vlček

| a | Připomínky k románu "Dobrého vojáka Švejka" | 20.3.1956 |

| Graf von Harrach, Otto |  | |||

| *10.2.1863 Praha - †10.9.1935 Hrádek u Nechanic | |||||

| |||||

Count von Harrach and his wife Karoline

Harrach is mentioned in connection with Gefreiter Peroutka who according to his own explanation took leave from the camp in Királyhida to have a look at the counts greenhouse.

Background

Harrach was a count of the Czech-Austrian noble family Harrach who owned Schloss Prugg in Bruck an der Leitha. Count von Harrach was from 1909 "majorat" of the noble family and was as such the formal owner of the caste. He was son of the Czech politician Johann Nepomuk von Harrach. During World War I he and his wife ran a hospital in the castle.

Otto Johann Nepomuk Bohuslaw Maria Scholastika Graf von Harrach zu Rohrau und Thannhausen

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Potom tam ještě k nim strčili frajtra Peroutku od 13. marškumpanie, který, když se včera rozšířila pověst po lágru, že se jede na posici, se ztratil a byl ráno patrolou objeven „U bílé růže“ v Brucku. Vymlouval se, že chtěl před odjezdem prohlédnout známý skleník hraběte Harracha u Brucku a na zpáteční cestě že zabloudil, a teprve ráno celý unavený že dorazil k „Bílé růži“. (Zatím spal s Růženkou od „Bílé růže“.)

Sources: Wolfgang Gruber, Robert Thurner

| Korporal Havlík |  | |||

| |||||

Havlík reported that the railway carriages were ready at Bruck station.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Tento optimistický názor nesdílela 13. marškumpačka, která telefonovala, že právě se vrátil kaprál Havlík z města a slyšel od jednoho železničního zřízence, že už vozy jsou na stanici.

| Novotný, Josef |  | |||

| |||||

Josef Novotný from Dražov appears in an anecdote. See Eduard Doubrava.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] A tu se vám von rozpřáh, já jsem se uhnul a on rozbil tabuli na přední plošině, tu velkou před řidičem. Tak nás vysadili, vodvedli a na komisařství se ukázalo, že byl proto tak nedůtklivý, poněvadž vůbec se nejmenoval Josef Novotný, ale Eduard Doubrava a byl z Montgomery v Americe a zde byl navštívit příbuzný, ze kterých pocházela jeho rodina.“

| Novotný, Antonín |  | |||

| |||||

Tonda Novotný from Dražov appears in an anecdote. See Eduard Doubrava.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Tak jsem mu ještě řekl bližší podrobnosti, že v Dražově byli dva Novotní, Tonda a Josef.

| Doubrava, Eduard |  | |||

| |||||

,13.4.1924

Eduard Doubrava was a Czech emigrant from Montgomery in the United States who was visiting his homeland when Švejk met him on a tram and mistook him for Josef Novotný. It is in this anecdote Švejk reveals where he is from, and even mentions the names of his parents.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] A tu se vám von rozpřáh, já jsem se uhnul a on rozbil tabuli na přední plošině, tu velkou před řidičem. Tak nás vysadili, vodvedli a na komisařství se ukázalo, že byl proto tak nedůtklivý, poněvadž vůbec se nejmenoval Josef Novotný, ale Eduard Doubrava a byl z Montgomery v Americe a zde byl navštívit příbuzný, ze kterých pocházela jeho rodina.“

| Kadett Biegler, Adolf |  | |||

| |||||

,27.4.1924

Biegler is mentioned 157 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Biegler is a cadet in 11. Marschkompanie and plays an important part at the start of Part Three. He is beside Leutnant Dub the main target of Hašek's ridicule of upwardly mobile monarchists in k.u.k. Heer. The author initially describes him as "the biggest idiot in the entire company" and moreover he had a pale apparence.

Biegler had studied military history diligently and is keen to show off his knowledge, which raises contempt and laughter amongst his officer colleagues. He also boasts about his blue-blood pedigree whereas the author can reveal the his father is a honest trader is furs and skins. It is also revealed that Biegler is from Budějovice.

Biegler takes centre stage on the train between Moson and Győr where he discovers the error where the mixed up books by Ludwig Ganghofer renders the company's cipher key worthless, thus embarrassing Hauptmann Ságner in front of his fellow officers. His joy is short-lived though; Ságner puts him severely in place and Biegler drenches the humiliation in a concoction of cognac and cream rolls that his mother had sent him. The awful outcome is that he shits himself so thoroughly during his unforgettable trip on the way to Budapest that he ends up in a cholera clinic in Újbuda, and from there he is dispatched to Tarnov for recuperation.

Now he leaves the story, only to reappear towards the end of the novel. Here he is partially redeemed in the eyes of the reader as he silences the even more idiotic Leutnant Dub.

Background

The inspiration for the character Biegler is without doubt Hans Bigler, a young reserve officer who served with Jaroslav Hašek in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 during the spring and summer of 1915.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Ve dveřích se objevil celý bledý kadet Biegler, největší blbec u kumpanie, poněvadž v jednoročácké škole se snažil vyniknout svými vědomostmi. Kývl Vaňkovi, aby za ním vyšel na chodbu, kde s ním měl dlouhou rozmluvu.

| Žlábek |  | |||

| |||||

Žlábek was a soldier Kadett Biegler wanted to tie up as punishment for having cleaned his rifle with kerosene.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Je to kus vola,“ řekl k Švejkovi, „tady u naší maršky máme ale exempláře. Byl taky u bešprechungu, a když se rozcházeli, tak nařídil pan obrlajtnant, aby všichni zugskomandanti udělali kvervisitu a aby byli přísní. A teď se mne přijde zeptat, jestli má dát uvázat Žlábka, poněvadž ten si vypucoval kvér petrolejem.“

| Šic |  | |||

| |||||

Šic was a pious man from Pořící who served with Švejk during a maneouvre in the Prácheňsko area. When drunk Šic removed a statue of Jan Nepomucký from a roadside shrine and kept him for good luck.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Sloužil se mnou nějakej poříckej Šic, hodnej člověk, ale nábožnej a bojácnej. Ten si představoval, že manévry jsou něco hroznýho, že lidi na nich padají žízní a saniteráci že to sbírají jako padavky na marši. Proto pil do zásoby, a když jsme vyrazili na manévry z kasáren a přišli k Mníšku, tak říkal: ,Já to, hoši, nevydržím, mě může zachránit jen sám pán bůh.’

|

II. At the front |

| |

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 16.5.2024 |