Švejk's journey on a of Austria-Hungary from 1914, showing the military districts of k.u.k. Heer. The entire plot of The Good Soldier Švejk is set on the territory of the former Dual Monarchy.

The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (mostly known as The Good Soldier Švejk) by Jaroslav Hašek is a novel that contains a wealth of geographical references - either directly through the plot, in dialogues or in the author's narrative. Hašek was himself unusually well travelled and had a photographic memory of geographical (and other) details. It is evident that he put a lot of emphasis on geography: Eight of the 27 chapter headlines in the novel contain geographical names.

This web site will in due course contain a full overview of all the geographical references in the novel; from Prague in the introduction to Klimontów in the unfinished Part Four. Continents, states (also defunct), cities, market squares, city gates, regions, districts, towns, villages, mountains, mountain passes, oceans, lakes, rivers, caves, channels, islands, streets, parks and bridges are included.

The list is sorted according to the order in which the names appear in the novel. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2008) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's translation from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by these examples: Sanok a location where the plot takes place, Dubno mentioned in the narrative, Zagreb part of a dialogue, and Pakoměřice mentioned in an anecdote.

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (591)

Show all

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (591)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60) II. At the front

II. At the front  2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (38)

1. Across Magyaria (38) 2. In Budapest (38)

2. In Budapest (38) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50) 4. Forward March! (42)

4. Forward March! (42)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

7. Švejk goes in the military | |||

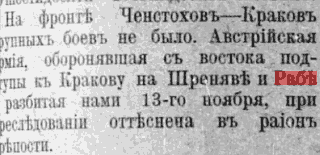

| Raba |  | ||||

| ||||||

Raba by Dobczyce.

, 30.11.1914

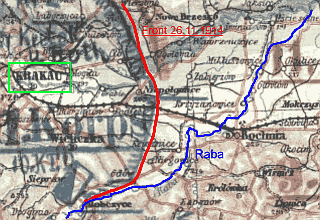

Map appendix to "Kaiserbericht", 26 November 1914.

© ÖStA

Raba is mentioned by the author at the beginning [I.7]. Austrian troops fled across the river and Austria was in a very bad way. The author calls it Ráb, which can easily be confused with the better known river Raab which flows through Austria and Hungary.

In [I.14] the river is mentioned again in a similar description. See Dunajec.

Background

Raba is a river in Galicia which empties into Vistula east of Kraków, in the south of current Poland. In 1914 the entire river flowed on Austrian territory.

The event referred to in the novel is by near certainty the situation on the Galician battlefield in late November 1914. On the 26 November, during the advance on Kraków, the Russian 3rd Army led by Radko Dimitriev crossed the river, some units having reached and crossed it the evening before by Mikluszowice. According to Russian reports the Austro-Hungarian army retreated in disorder and suffered from low morale. They took up new defensive positions west of the river, on the line Dobczyce - Niepołomice, and by the end of the month they had retreated to Wieliczka, only 13 kilometres south-east of Kraków.

This situation persisted until 8 December when the Russians were pushed eastwards towards Dunajec during the battle of Limanowa. It was during the advance on Kraków that Czech volunteers in the Russian army, Česká družina, first were in action against k.u.k. Heer. Wieliczka was also the westernmost point the imperial Russian army ever reached.

Mentioned in a short story

The river was mentioned by the author already in 1908 in the story Ve vesnici u řeky Rábu (In a village by the river Raba), printed in Besedy lidu. This strongly suggests that Jaroslav Hašek had visited the area by the river, most likely during the summer of 1903 when he stayed in Kraków.

Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg, Band I.

Südlich der Weichsel hatte sich im Verlaufe des 25. das Vorgehen des Russen zunächst nicht geltend gemacht. Erst am 26. vordem Hellwerden überschritt das XI. Korps die untere Raba und drängte die Gruppe Obst. Brauner auf die Linie Dziewin-Grobla zurück. Zu derselben Stunde griff das feindliche IX. Korps Bochnia an, das von der 11. ID. verteidigt wurde. Weiter südlich rückten stärkere russische Kräfte von G(Lipnica) her gegen die 30. ID. vor. Die auf Rajbrot entsandte 10. KD. war schon in der Nacht zum 25. auf Dobczyce zurückgenommen worden, da sie dringend einiger Erholung bedurfte. In solcher Lage meldete FZM. Ljubičić um 9h vorm., daß seine völlig erschöpften Truppen zu einem nachhaltigen Widerstand in der weitausgedehnten Front zwischen der Weichsel und der Straße Gdów-Muchówka nicht mehr befähigt seien. Inzwischen hatte die 11. ID. unter erheblichen Verlusten dem schweren russischen Druck bei Bochnia nachgeben müssen. FZM. Ljubičić ordnete daher um 9h45 vorm. den Rückzug seiner ganzen Gruppe in die vorbereitete Stellung Dobczyce-Niepołomice an.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] V době, kdy lesy na řece Rábu v Haliči viděly utíkat přes Ráb rakouská vojska a dole v Srbsku rakouské divise jedna za druhou dostávaly přes kalhoty to, co jim dávno patřilo, vzpomnělo si rakouské ministerstvo vojenství i na Švejka, aby pomohl mocnářství z bryndy.

[I.14.5] Zatímco masy vojsk připnuté na lesích u Dunajce i Rábu stály pod deštěm granátů a velkokalibrová děla roztrhávala celé setniny a zasypávala je v Karpatech a obzory na všech bojištích hořely od požárů vesnic i měst, prožíval nadporučík Lukáš se Švejk nepříjemnou idylu s dámou, která utekla svému muži a dělala nyní domácí paní.

Also written:RábHašek

Literature

- Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914-19181930 - 1936

- Bitva u Limanově

- Za svobodu - 1. díl

- Kaiserbericht vom 26.11.1914

- Ve vesnici u řeky RábuJaroslav Hašek25.9.1908

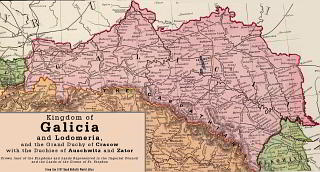

| Galicia |  | ||||

| ||||||

Some places in Galicia that are mentioned in the novel (orange).

,5.7.1908

Galicia is mentioned first time by the narrator at the start of [I.7]. Here he informs the reader that Austrian forces are fleeing across the river Raba in Galicia. Towards the end of the novel, from [III.4] and throughout the unfinished Part Four the plot takes in its entirety place in Galicia. Many places in the region are mentioned, or form part of the plot. The most important of these are Kraków, Sanok, Przemyśl, Lwów and Sokal. The plot itself ends in Galicia, near Żółtańce.

Background

Galicia was until 1918 an Austrian "Kronland" north of the Carpathians. As a political unit it was known as Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien from 1846 until 1918. The population at the time was mixed: Poles, Germans, Jews and Ukrainians were the largest groups. Galicia enjoyed a large degree of autonomy and Polish had status as official language within the administration. The "polonisation" of the region enjoyed support even from the emperor. The administrative capital was Lwów which was a Polish enclave in an otherwise Ukrainian dominated region.

In September 1914 Russia occupied most of Galicia, and by the 12th k.u.k. Heer had withdrawn behind the river San. By late November the enemy had advanced much further west and even threatened Kraków. From 2 May 1915 and throughout the summer most of Galicia was reconquered by the Central Powers. It was during these offensives that Jaroslav Hašek took part as a soldier from 11 July to 24 September.

From 1918 the region became part of Poland, and in 1939 and it was partitioned between Germany and the Soviet Union. From 1945 it was split between Poland and the USSR, and from 1991 between Poland and Ukraine.

Hašek in Galicia

Apart from his stay during the war the author knew Galicia well from his wanderings after the turn of the century. He traveled in the "Kronland" both in 1901 and 1903; more precisely in and around Kraków and Tarnów. He wrote several stories set in the region, two of them with Jewish themes from a town he named Zapustna (not identified).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] V době, kdy lesy na řece Rábu v Haliči viděly utíkat přes Ráb rakouská vojska a dole v Srbsku rakouské divise jedna za druhou dostávaly přes kalhoty to, co jim dávno patřilo, vzpomnělo si rakouské ministerstvo vojenství i na Švejka, aby pomohl mocnářství z bryndy.

[I.9] Byly to fotografie různých exekucí, provedených armádou v G(Haliči) a v Srbsku.

[II.1] Stačilo to nejmenší, a důstojník se již loučil se svou posádkou a putoval na černohorské hranice nebo do nějakého opilého, zoufalého garnisonu v špinavém koutě Haliče.

[II.2] Přesunutí našich vojsk ve východní Haliči dalo původ k tomu, že některé ruské vojenské části; překročivše Karpaty, zaujaly pozice ve vnitrozemí naší říše, čímž fronta byla přesunuta hlouběji k západu mocnářství.

[II.4] I vy jste objednáni připojiti se k výletu do Haliče. Nastupte cestu s myslí veselou a lehkým, radostným srdcem.

[II.4] S city povznesenými nastoupíte pout do krajin, o kterých již starý Humboldt pravil: "V celém světě neviděl jsem něco velkolepějšího nad tu blbou Halič". Hojné a vzácné zkušenosti, jichž nabyla naše slavná armáda na ústupu z Haliče při prvé cestě, budou našim novým válečným výpravám jistě vítaným vodítkem při sestavování programu druhé cesty.

Also written:HaličczGaliziendeGalicjanoGalicjaplГаличинаua

Literature

- The Internment of Russophiles in Austria-Hungary17.11.2020

- ChaluteJaroslav Hašek

- Pan Lazar Adamus z JarochówaJaroslav Hašek23.6.1907

- Židovská povídka ze Zapustny v HaličiJaroslav Hašek5.7.1908

| Kraków |  | |||

| |||||

Kraków, Główny Rynek, vor 1905

,1912

Hašek's story printed in Cleveland.

Dennice novověku,18.5.1905

Kraków is mentioned by Švejk in conversation with Mrs. Müllerová when he informs her that he has been called up for service. Here it is revealed that the Russians have almost reached the city, something that corresponds with the military situation around 1 December 1914.

In [I.15] the city is mentioned again in a highly treasonous conversation between Švejk and another soldier: the tsar is already there and by Náchod the thunder from Russian cannons can be heard.

Background

Kraków is a city in southern Poland and the second largest city in the country with more than 700,000 inhabitants. It has a beautiful and well preserved historic core and is on UNESCO's World Heritage list.

Until 1918 Kraków was part of Cisleithania and even enjoyed the status as a separate crown land within Galicia.

Kraków never experienced fighting during WWW1, but in late November 1914 the situation was critical as Russian forces reached positions only 13 kilometres east of the city before they were pushed back to the river Dunajec during the battle of Limanowa.

Hašek in Kraków

Jaroslav Hašek visited the area in the summer of 1901 and again in July 1903[a]. According to his own account he was on the latter occasion arrested after having crossed over to Russian Poland without his documents in proper order. In 1905 Světozor published the story Mezi tuláky (Amongst tramps), where Hašek described his stay in the city prison[c]. The story even appeared in the Czech-American newspaper Dennice novověku (Cleveland, Ohio) in May that year, and in addition it was published by Besedy lidu.

Military

In accordance with the recruitment districts infantrymen from Kraków were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 13 (Krakau) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 16 (Krakau). It was a major garrison city, and was protected by one of the strongest fortress complexes in the empire. The city was the head-quarter of Korpsbezirk Nr. 1. Most branches of the armed forces were represented here and amongst them were units that we know from The Good Soldier Švejk: k.u.k. Kavallerietruppendivision Nr. 7, Traineskadron Nr. 3, and k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 16.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] „Panenko Maria,“ vykřikla paní Müllerová, „co tam budou dělat?“ „Bojovat,“ hrobovým hlasem odpověděl Švejk, „s Rakouskem je to moc špatný. Nahoře nám už lezou na Krakov a dole do Uher.

[I.15] Když oba potom ještě dále tlumočili názor českého člověka na válku, voják z kasáren opakoval, co dnes slyšel v Praze, že u Náchoda je slyšet děla a ruský car že bude co nejdřív v Krakově.

Also written:KrakovczKrakaude

Literature

- Mezi tulákyJaroslav Hašek18.5.1905

- Krakov Královský22.4.1910

- Starobylé město Krakov2.10.1914

| a | Toulavé house | 1971 | |

| b | Procházka přes hranice | 1915 | |

| c | Mezi tuláky | Jaroslav Hašek | 10.2.1905 |

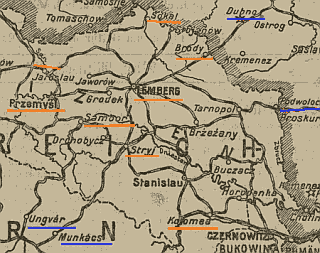

| Hungary |  | ||||

| ||||||

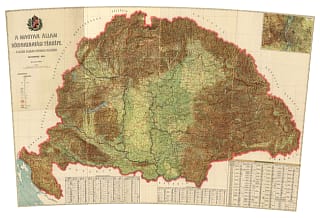

Magyar Állam közigazgatási térképe (1914)

, 1907

Hungary is mentioned by Švejk in the conversation with Mrs. Müllerová when he informs her that he has been called up for military service. The Russians are said to be in Hungary already. Later on, the action in parts of Book II and nearly all of Book III takes place in the kingdom of Hungary. Švejk had his first encounter with Hungary in Királyhida and left its territory in Palota. It is also revealed that he had been in Hungary before the war during manoeuvres by Veszprém.

Note that the common Czech term for Hungary, Maďarsko, is never used in the novel.

Background

Hungary (Magyar Királyság) is in this context the historical kingdom that from 1867 to 1918 was in a royal union with the Austria and which together with them constituted Austria-Hungary. The kingdom roughly included modern Hungary, Slovakia, Burgenland, Transylvania and the parts of present Ukraine that lies west of the Carpathians. Head of state was king I. Ferenc József (i.e. Franz Josef). In addition Croatia was a nominal kingdom under Hungarian rule with considerable autonomy.

The population in 1910 was slightly above 21 million of which less than half were ethnic Hungarians. The capital during this period was Budapest. The kingdom was also known as Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, and after 1867 also as Transleithanien, the land beyond the Leitha. The kingdom shared borders with Austria, Romania and Serbia.

After the 1867 Ausgleich Hungary exploited its new found autonomy to impose a policy of magyarisation on its minorities, causing widespread resentment amongst the other nationalities of the kingdom. The Treaty of Trianon in 1920 stripped Hungary of two thirds of its population and territory, but the kingdom continued to exists formally until 1946, although without a king. Since then Hungary has been a republic.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] „Panenko Maria,“ vykřikla paní Müllerová, „co tam budou dělat?“ „Bojovat,“ hrobovým hlasem odpověděl Švejk, „s Rakouskem je to moc špatný. Nahoře nám už lezou na Krakov a dole do Uher.

[I.13] Ten padne v Karpatech s mou nezaplacenou směnkou, ten jde do zajetí, ten se mně utopí v Srbsku, ten umře v Uhrách ve špitále.

[II.3] "To už se dávno vědělo," řekl k němu po cestě jednoroční dobrovolník, "že nás přeloží do Uher.

[II.4] Jest rozhodné povinností úradu vyšetriti tento zlocin a optati se vojenského velitelství, které jisté již se touto aférou zabývá, jakou úlohu v tom bezpríkladném štvaní proti príslušníkum Uherského království hraje nadporucík Lukasch, jehož jméno uvádí se po meste ve spojitosti s událostmi posledních dnu, jak nám bylo sdeleno naším místním dopisovatelem, který sebral již bohatý materiál o celé afére, která v dnešní vážné dobe prímo kricí.

[II.4] Že se věcí bude zabývat peštská sněmovna, je nabíledni, aby nakonec se ukázalo jasné, že čeští vojáci, projíždějící Uherským královstvím na front, nesmí považovat zemi koruny svatého Štěpána, jako by ji měli v pachtu.

[II.4] Divizijní soud ve svém přípise na velitelství našeho pluku," pokračoval plukovník, "přichází k tomu mínění, že se vlastně o nic jiného nejedná než o soustavné štvaní proti vojenským částem přicházejícím z Cislajtánie do Translajtánie.

Also written:UhryHašekMagyariaSadlonMaďarsko/Uhersko/UhryczMagyar Királysághu

Literature

- Na svazích HegyalyeJaroslav Hašek3.6.1904

| Piedmont |  | |||

| |||||

Places occupied by Austria in May 1859 highlighted red

Piedmont appears in the popular folk song Jenerál Windischgrätz a vojenští páni that Švejk sings in his sick-bed after having been called up by the army for a medical examination.

Background

Piedmont was in 1914 as today a province of Italy. It is located in the north-western part of the country and borders France and Switzerland. The capital is Torino.

The song refers to events during the second Italian war of independence in 1859. On 27 April war erupted between Austria and the kingdom of Sardinia (that Piedmont was part of). At the start of the war, before Sardinia's ally France had come to her aid, Austrian forces crossed into Piedmont. They crossed the border river Ticino on 29 April, and occupied Novara, Montara, Vercelli and the surrounding land west of the river. The four bridges the song mentions may refer to the river Ticino or the river Sesia to the west (which was as far as the invaders got). By early June the Austrian forces had withdrawn east of Ticino and all of Piedmont was again under allied control.

The war ended in victory for Sardinia and France, and as a result Austria had to cede most of Lombardia. The decisive battle stood at Solferino on 24 June 1859, mentioned in the same song. The ceasefire was effectuated on 12 July (il armistizio de Villafranca).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Uděšená paní Müllerová pod dojmem strašného válečného zpěvu zapomněla na kávu a třesouc se na celém těle, uděšena naslouchala, jak dobrý voják Švejk dál zpívá na posteli:

S panenkou Marií a ty čtyry mosty, postav si, Pimonte, silnější forposty, hop, hop, hop!

Also written:PimonteHašekPiemontczPiemontdePiedmontfr

Literature

| Solferino |  | ||||

| ||||||

Solferino is mentioned in the song Jenerál Windischgrätz a vojenští páni that Švejk patriotically tunes up after having been called up for army service and immediately is struck by a fit of rheumatism.

Background

Solferino is a small town in Italy, slightly south of Lake Garda. During the second war of Italian independence Austria lost the decisive battle here against France and Sardinia on 24 June 1859. Austria was forced to cede Lombardia and this outcome paved the way for the unification of Italy.

The origins of the Red Cross

Henry Dunant took part in the battle and moved by witnessing the sufferings of the soldiers he was later to found the Red Cross. This was the last major battle in history where the monarchs commanded their armies directly. Emperor Franz Joseph I. withdrew as Austrian commander-in-chief after this battle.

Windischgrätz

Some verses of the song about General Windischgrätz are also quoted in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí and in a context that is very similar[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Byla bitva, byla, tam u Solferina, teklo tam krve moc, krve po kolena, hop, hop, hop!

Krve po kolena a na fůry masa, vždyť se tam sekala vosumnáctá chasa, hop, hop, hop!

Literature

| a | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Austria-Hungary |  | ||||

| ||||||

Austria-Hungary is mentioned first time by the author in this way: "and so, at a time when Vienna wished that all the nations of Austria-Hungary would offer to the empire its most exquisite specimens of loyalty and dedication, Doctor Pávek prescribed bromide against Švejk's patriotic enthusiasm. He also recommended that this brave and good former infantryman think no more about the military".

In [II.4] the monarchy is repeatedly mentioned in the article by deputy Barabás in Pester Lloyd.

Otherwise the state of Austria-Hungary and its institutions is the butt of Jaroslav Hašek's satire throughout the novel. The entire plot takes place on the territory of the Dual Monarchy, from Prague in the west to the river Bug to the east. It also passes important cities like Vienna, Lwów and Budapest. The monarchy's most important traffic route, the Danube, is also included. The novel has hundreds of references to places in the monarchy.

Background

Austria-Hungary was a political unit that existed from 8 June 1967 to 21 October 1918 in the form of a personal union between Austria and Hungary. By area and population (about 52 million) it was one of the largest states in Europe. Austria-Hungary was a multi-ethnic state with 11 official languages and even more ethnic groups. It was a constitutional monarchy with freedom of worship and universal suffrage, although with authoritarian leanings. This was first and foremost the case in Hungary where the ethnic minorities had a far weaker position than in the Austrian part of the empire.

With its mixed population Austria-Hungary was vulnerable to internal strife, which was particularly evident in times of crisis. There were also large differences in economic and social development between the various parts of the monarchy. The present Czech Republic and Austria had mostly reached an advanced stage of industrial development, whereas the Balkans, parts of Hungary and Galicia were relatively backward agrarian societies.

Until Ausgleich in 1867 the Habsburg state was known as the Austrian Empire. Hungary took advantage of defeat by Prussia the previous year to force through a redistribution of power that put them on equal terms with Austria. These privileges granted to the Hungarians provoked great resentment amongst the other peoples of the empire, particularly the Slavs. The Czechs felt particulalrly aggrieved as they contributed nearly 25 per cent of the tax income (although this number includes the Germans of Bohemia and Moravia).

The state was also called the Dual Monarchy or the Danube Monarchy. Emperor Franz Joseph I. was emperor of Austria and king of Hungary respectively. The river Leitha formed in part the boundary between the two parts of the monarchy, which therefore were unofficially referred to by the Latin terms Cisleithania and Transleithanien.

The official name in German was Die im Reichsrat vertretenen Königreiche und Länder und die Länder der heiligen ungarischen Stephanskrone.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] A tak v době, kdy Vídeň si přála, aby všichni národové Rakousko-Uherska dávali nejskvělejší příklady věrnosti a oddanosti, předepsal doktor Pávek Švejkovi proti jeho vlasteneckému nadšení brom a doporučoval statečnému a hodnému vojínu Švejkovi, aby nemyslil na vojnu.

[II.4] Vedení války vyžaduje součinnost všech vrstev obyvatelstva rakouskouherského mocnářství.

[II.4] ... o čemž svědčí celá řada vynikajících českých vojevůdců, z nichž vzpomínáme slavné postavy maršálka Radeckého a jiných obranců rakousko-uherského mocnářství.

Also written:Rakousko-UherskoczÖsterreich-UngarndeAusztria-MagyarországhuAusterrike-Ungarnnn

Literature

- The First World War and the end of the Dual Monarchy2014

- Veltzés Internationaler Armee-Almanach1914

- Austra-Hungary

- 1914 - 2014, 100 Jahre erster Weltkrieg

- Die österreicisch-ungarische Monarchie im Wort und Bild

- Det Österrig-ungarske monarki1896

- Österreich-Ungarn

- Österreich-Ungarn

- Franzisco-Josephinische Aufnahme (1869-1887)

- Erster Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie

| Belgrade |  | |||

| |||||

,30.7.1914

,1924-1928

Belgrade is in the novel expressed first time through Švejk's patriotic rallying cry from the wheelchair: "To Belgrade, to Belgrade!". The city is also mentioned in Királyhida when the author relates the story about the false one year volunteer Zugsführer Teveles.

Background

Belgrade was in 1914 capital of the kingdom of Serbia and after the war it became capital of Yugoslavia. Its position was very exposed, right on the border with Hungary which at the time ruled Vojvodina and Banat on the opposite banks of the rivers Sava and Danube. The current urban district of Zemun west of Sava at the time belonged to Hungary. The first shots of the world war were fired against Belgrade from river boats (monitors) on 29 July 1914.

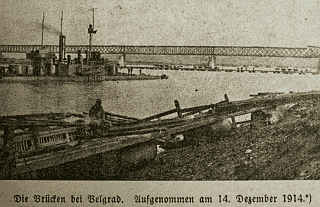

In late November the city was abandoned, and k.u.k. Wehrmacht duly entered on 2 December 1914. But facing a Serbian counter-attack their position became untenable and the occupiers were forced out by the 15th. Belgrade didn't succumb again until 9 October 1915 when Serbian resistance collapsed after Bulgaria and Germany came to the aid of Austria-Hungary. Belgrade was liberated on 1 November 1918 by Serbian and French forces.

IR. 91 and Belgrade

Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 was fighting by the river Kolubara at the time Belgrade was occupied, and during the next two weeks they withdraw north towards the city. It was from here they escaped across the Sava to safety on 14 and 15 December. The regiment was totally decimated after the battle and retreat from Kolubara, and by the time they withdrew from Belgrade they were in disarray, split into smaller groups, and according to interim regiment commander major Kießwetter discipline broke down and cases of plundering were observed even back on Hungarian soil in Zemun, accompanied by widespread drunkenness. Three entire companies were captured during the retreat[a].

Four of the officers we know as models for characters from The Good Soldier Švejk took part in the battle of Kolubara and the traumatic retreat: Rudolf Lukas, Čeněk Sagner (until 27 November) and Jan Eybl (from 30 November). The commander of the 2nd battalion, Franz Wenzel, reported ill during the last week of the retreat.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

Beograd is in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí mentioned and exactly the same settings as in The Good Soldier Švejk. When Švejk is pushed to c.k. policejní ředitelství in a wheel-chair, he shouts to the crowd: "To Belgrade! To Belgrade!" Later the fall of Belgrade in early December 1914 is referred to.[1]

Na rohu Krakovské ulice dav zmlátil tři buršáky a průvod za zpěvu "Nemelem, nemelem" dostal se až k BVodičkově ulici, kde dobrý voják Švejk vztyčuje se bolestí ve vozíku a rozmachuje kolem berlemi, zvolal: "Ještě jednou na Bělehrad, na Bělehrad!" A vtom již do toho vrazila policie pěší i jízdní.

Když padl Bělehrad, Franz Rypatschek z velkého nadšení pomaloval se černě a žlutě a šel tak vzdát hold za šestý okres.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Stará žena, strkající před sebou vozík, na kterém seděl muž ve vojenské čepici s vyleštěným „frantíkem“, mávající berlemi. A na kabátě skvěla se pestrá rekrutská kytka. A muž ten, mávaje poznovu a poznovu berlemi, křičel do pražských ulic: „Na Bělehrad, na Bělehrad!“

[II.3] Vodička se zasmál: „To máš na frontě na denním pořádku. Vypravoval mně můj jeden kamarád, je teď taky u nás, že když byl jako infanterák pod Bělehradem, jejich kumpačka v gefechtu vodstřelila si svýho obrlajtnanta, taky takovýho psa, který zastřelil sám dva vojáky na pochodu, poněvadž už dál nemohli.

[II.4] Když si vzpomenu, že pod Bělehradem stříleli Maďaři po našem druhém maršbataliónu, který nevěděl, že jsou to Maďaři, kteří po nich střílí, a počal pálit do deutschmajstrů na pravém křídle, a deutschmajstři zas si to také spletli a pustili oheň po bosenském regimentu, který stál vedle.

Sources: Rudolf Kießwetter

Also written:BělehradczBelgraddeБеоградse

Literature

| a | Belgrad | Rudolf Kießwetter | 1924-1928 |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Václavské náměstí |  | ||||

| ||||||

Václavské náměstí is mentioned in the famous scene when Švejk was wheeled down the square in a wheelchair by Mrs. Müllerová, on the way to the call-up board. A crowd of a few hundred had gathered round them.

Background

Václavské náměstí is the most famous square in Nové město (New Town) if not in the whole of Prague. The square is the centre of Prague's commercial district and stretches from the National Museum north towards Staré město (Old Town). It is named after the Czech national saint, the Holy Václav.

Jaroslav Hašek was well known in the editorial offices in the street as he worked with both České slovo and Národní politika. These newspapers printed many of his stories before the war.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, during the interrogation of Švejk at k.u.k. Militärgericht Prag, the good soldier is accused of creating upheaval at Wenceslas Square.[1]

"Tak, tak," poznamenal veselý auditor, "vy jste tedy provedl švandu na Václavském náměstí. Byla to legrace, co říkáte, Švejku?"

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Na Václavském náměstí vzrostl zástup kolem vozíku se Švejkem na několik set hlav a na rohu Krakovské ulice byl jím zbit nějaký buršák, který v cerevisce křičel k Švejkovi: „Heil! Nieder mit den Serben!“ Na rohu Vodičkovy ulice vjela do toho jízdní policie a rozehnala zástup.

Also written:Wenceslas SquareenWenzelplatzdeWenselsplassenno

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Krakovská ulice |  | |||||

| |||||||

The corner of Václavské nám. and Krakovská ulice

Krakovská ulice is mentioned because a German-speaking student was beaten up by the crowd on the corner between Krakovská and Václavské náměstí. He had shouted "Heil! Nieder mit den Serben!"

Background

Krakovská ulice is a side street to Václavské náměstí, leading northwards, ending at the southern end of the latter.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the street is also mentioned and the theme is the same as in the novel: Švejk is pushed to the draft commission in a wheel-chair. Here it is however his servant Bohuslav and not Mrs. Müllerová who does the heavy task.[1]

Na rohu Krakovské ulice dav zmlátil tři buršáky a průvod za zpěvu "Nemelem, nemelem" dostal se až k Vodičkově ulici, kde dobrý voják Švejk vztyčuje se bolestí ve vozíku a rozmachuje kolem berlemi, zvolal: "Ještě jednou na Bělehrad, na Bělehrad!" A vtom již do toho vrazila policie pěší i jízdní.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Na Václavském náměstí vzrostl zástup kolem vozíku se Švejkem na několik set hlav a na rohu Krakovské ulice byl jím zbit nějaký buršák, který v cerevisce křičel k Švejkovi: „Heil! Nieder mit den Serben!“ Na rohu Vodičkovy ulice vjela do toho jízdní policie a rozehnala zástup.

Also written:Krakow streetenKrakauerstrassede

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Vodičkova ulice |  | |||||

| |||||||

Vodičkova ulice is mentioned becaused the crowd that followed Švejk were dispersed by mounted police on the corner between Vodičková and Václavské náměstí.

The street appears again in [I.13] when Feldkurat Katz and Švejk drive through in a horse cab on the way Vojenská nemocnice na Karlově náměstí to administer the last rites.

Background

Vodičkova ulice is the busiest side street to Václavské náměstí on the north-western side. Many tram lines pass through this street which is also in a busy shopping area.

The good soldier Švejk in captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí the street is also mentioned and the theme is the same as in the novel: Švejk is pushed to the draft commission in a wheel-chair. Here it is however his servant Bohuslav and not Mrs. Müllerová who does the heavy task.[1]

Na rohu Krakovské ulice dav zmlátil tři buršáky a průvod za zpěvu "Nemelem, nemelem" dostal se až k Vodičkově ulici, kde dobrý voják Švejk vztyčuje se bolestí ve vozíku a rozmachuje kolem berlemi, zvolal: "Ještě jednou na Bělehrad, na Bělehrad!" A vtom již do toho vrazila policie pěší i jízdní.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Na Václavském náměstí vzrostl zástup kolem vozíku se Švejkem na několik set hlav a na rohu Krakovské ulice byl jím zbit nějaký buršák, který v cerevisce křičel k Švejkovi: „Heil! Nieder mit den Serben!“ Na rohu Vodičkovy ulice vjela do toho jízdní policie a rozehnala zástup.

[I.13] A Švejk do toho zvonil, drožkář sekal bičem dozadu, ve Vodičkové ulici nějaká domovnice, členkyně mariánské kongregace, ...

Also written:Wassergassede

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Střelecký ostrov |  | |||||

| |||||||

The mustering took place in the garden restaurant

Střelecký ostrov was the location where Švejk appeared before Odvodní komise (the military draft commission). He was pushed there in a wheelchair by Mrs. Müllerová, guarded by two mounted policemen. Here he was welcomed by Doctor Bautze who uttered the now famous words: "Das ganze tschechische Volk ist eine Simulantenbande" (The whole Czech nation is a pack of malingerers).

Background

Střelecký ostrov is an island in Vltava in Prague, located below Most Legií near the western bank of the river. In 1914 the island was already a popular recreation spot with a large restaurant located at the southern tip.

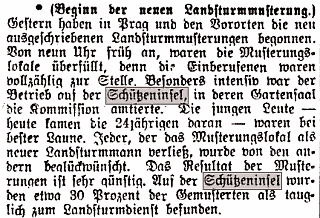

Landsturmmusterung

From 1 September 1914 this restaurant assumed a new role: the Landsturm (Home Guard) medical examinations took place here and continued at least through 1915. The first group to be called up were born in 1892, 1893 and 1894. The pass rate amongst them was above 50 per cent. Between 16 November and 31 December it was the turn of those born between 1878 and 1890.

In this age group the pass rate was much lower, around 30 per cent. Note that these call-ups only applied to men who had previously either been declared unfit for service, or had initially been deemed Tauglich, but were released from service later - in other words superarbitrated. Ordinary Landsturm soldiers above the age of 32 and who had always been fit were called up earlier in the war, and often fought as separate Landsturm regiments. See also Odvodní komise.

Hašek as domobranec

,17.11.1914

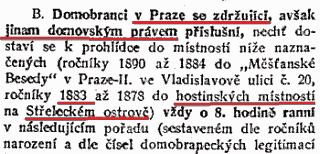

Army files refer to Jaroslav Hašek as Landsturminfanterist, later Landsturm Gefreiter mit Einjährig-Freiwilliger Abzeichen. It is therefore assumed that he was examined at Střelecký ostrov, and several sources confirm that he indeed was, amongst them Břetislav Ludvík. The examination that affected the age group of Jaroslav Hašek was announced in newspapers on 12 November 1914.

At Střelecký ostrov the following were to appear: those born between 1878 and 1990 who lived in Prague with Heimatrecht there AND those born between 1878 and 1883 resident in Prague but who had Heimatrecht elsewhere. Jaroslav Hašek, born in 1883 and with domicile rights in Mydlovary, indeed belonged to the latter category. The younger age-groups (1884-1990) with domicile rights outside Prague reported at Beseda. Those born in 1883 with domicile right outside Prague were examined from 13 to 15 of December and the author was surely amongst them. Those in his group who were deemed fit for service had to report on 15 February 1915.

Landšturmák Švejk

,12.11.1914

Švejk no doubt had Heimatrecht in the Czech south, otherwise he would not have served with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. This gives an indication of Švejk's age. If he was more than 36 he wouldn't have been called up in this round, and had he been younger than 30 he would have reported at Beseda. The fact that Švejk was superarbitrated and had to report at Střelecký ostrov means that he necessarily must have been a landšturmák aged between 30 and 36 in 1914. That unless the belonged to the younger group (aged 20-22) that reported in October 1914. This is however unlikely, because it is explicitly stated that Švejk was called up when the Austrians were fleeing across the Raba (which they did in late November).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Když Švejk revírnímu inspektorovi ukázal, že to má černé na bílém, že dne musí před odvodní komisi, byl revírní inspektor trochu zklamán; kvůli zamezení výtržnosti dal doprovázet vozík se Švejkem dvěma jízdními strážníky na Střelecký ostrov.

Also written:Schützeninselde

Literature

- Landsturmmusterung in Prag12.11.1914

- Prohlídka domobranců v Praze12.11.1914

- Schützeninsel, Grosse Verdi-Feier (mit IR91 Regimentskapelle)16.10.1913

- Vyhláška9.11.1914

- Anekdota o Jaroslavu Haškovi5.12.1918

| Bayonne |  | ||||

| ||||||

Mannlicher M95 bayonet

Bayonne is indirectly mentioned through the "bayonet", a weapon that is believed to have got its name from this French town. The weapon obviously appears throughout the novel, but is first mentioned as the two soldiers with mounted bayonets escort Švejk from Střelecký ostrov to Posádková věznice at Hradčany.

Background

Bayonne is a town in France that is believed to have provided the name for the bayonet, a bladed weapon typically mounted on rifles and used in close-quarter combat.

The bayonet was invented in the 17th century and was widely used in World War I as is evident from the text of the novel. The stock rifle of k.u.k. Heer, Mannlicher M95, could be supplied with several varieties. The weapon is in use also in moderne armies (2017).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Dva vojáci s bajonety odváděli Švejka do posádkové věznice. Švejk šel o berlích a s hrůzou pozoroval, že jeho revmatismus začíná mizet.

Literature

| Most císaře Františka I. |  | |||

| |||||

,21.6.1901

Most císaře Františka I. was the bridge above Střelecký ostrov where Mrs. Müllerová waited in vain for Švejk after his examination. It's name is not mentioned directly in the text, but the description leaves no doubt to what bridge is in question.

Background

Most císaře Františka I. is the former name of Most Legií, a bridge across Vltava in Prague, named after the last German-Roman emperor Franz I.. It was opened by Emperor Franz Joseph I. on 14 June 1901. It is a stone bridge, later renamed several times. It replaced a former chain bridge from 1841. See also Starej Procházka.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Paní Müllerová, která čekala nahoře na mostě s vozíkem na Švejka, když ho viděla pod bajonety, zaplakala a odešla od vozíku, aby se vícekrát k němu nevrátila.

Literature

| Malá Strana |  | ||||

| ||||||

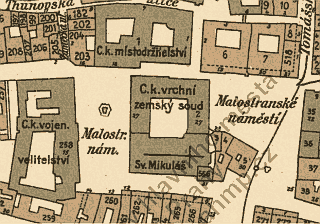

Malostranské náměstí and the Radetzky monument.

Malá Strana around 1910 with the important k.k. government institutions.

© AHMP

Malá Strana is mentioned as Švejk was led through this area on his way to the prison on Hradčany. Švejk definitely passed Malostranské náměstí on the way to jail, because he saluted the Marschall Radetzky monument that stood here until 1918.

The plot briefly takes place in Malá Strana again in [I.10] when Švejk is escorted to Feldkurat Katz and in [I.14] when he and Blahník plan the dog theft. Otherwise the places in the district appear in various anecdotes. See U Montágů, U krále brabantského, U svatého Tomáše.

Background

Malá Strana is one of the oldest districts of Prague. The name means "The Little Side" and was originally a short version of "Menší město pražské", "The lesser town of Prague". The district is situated on the western bank of the Vltava below Prague Castle. It borders Hradčany and Smíchov. Today it is no longer an administrative unit but still has status as a cadastral district. Until 1922 the district was equivalent to Praha (III).

Government institutions

In the times of the Dual Monarchy Malá Strana housed three of the empires most powerful representatives in Bohemia: k.k. Statthalterei, k.k. Landesgericht, and 8. Armeekorps (see Korpskommando). The first represented Vienna's executive power, during the war a dictatorship for all practical purposes. The second represented the judiciary, and the third the military authorities. The 8th Army Corps' domain was Prague and the areas to the south and west to the borders of Austria and Bavaria. The rest of Bohemia belonged to 9. Armeekorps in Litoměřice (Leitmeritz). The 8th army corps also commanded 9. Infanteriedivision to which Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 reported. The entire corps was mobilised on 26 July 1914 and most units were sent to Serbia where they suffered disastrous losses throughout the autumn.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Malá Strana had 20,374 inhabitants of which 17,910 (87 per cent) reported that they used Czech in their daily speech.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.7] Bajonety svítily v záři slunce a na Malé Straně obrátil se Švejk před pomníkem Radeckého k zástupu, který je vyprovázel: „Na Bělehrad! Na Bělehrad!“

[I.8] Já jsem původně také chtěl dělat blázna, náboženského šílence, a kázat o neomylnosti papežově, ale nakonec jsem si opatřil rakovinu žaludku od jednoho holiče na Malé Straně za patnáct korun.“

Also written:Kleinseitede

|

I. In the rear |

| |

7. Švejk goes in the military | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 14.5.2024 |