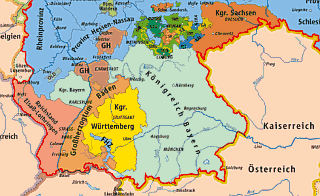

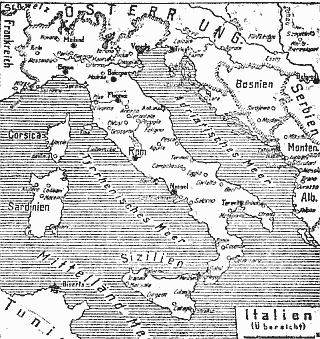

Švejk's journey on a of Austria-Hungary from 1914, showing the military districts of k.u.k. Heer. The entire plot of The Good Soldier Švejk is set on the territory of the former Dual Monarchy.

The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (mostly known as The Good Soldier Švejk) by Jaroslav Hašek is a novel that contains a wealth of geographical references - either directly through the plot, in dialogues or in the author's narrative. Hašek was himself unusually well travelled and had a photographic memory of geographical (and other) details. It is evident that he put a lot of emphasis on geography: Eight of the 27 chapter headlines in the novel contain geographical names.

This web site will in due course contain a full overview of all the geographical references in the novel; from Prague in the introduction to Klimontów in the unfinished Part Four. Continents, states (also defunct), cities, market squares, city gates, regions, districts, towns, villages, mountains, mountain passes, oceans, lakes, rivers, caves, channels, islands, streets, parks and bridges are included.

The list is sorted according to the order in which the names appear in the novel. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2024) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's translation from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by these examples: Sanok a location where the plot takes place, Dubno mentioned in the narrative, Zagreb part of a dialogue, and Pakoměřice mentioned in an anecdote.

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all

Places index of countries, cities, villages, mountains, rivers, bridges ... (592)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (60) II. At the front

II. At the front  2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (64) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (43) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (38)

1. Across Magyaria (38) 2. In Budapest (38)

2. In Budapest (38) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (50) 4. Forward March! (42)

4. Forward March! (42)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš | |||

| Na Zderaze |  | ||||

| ||||||

Pohled do ulice Na Zderaze uprostřed s domem čp. 271 na Novém Městě na nároží s ulicí Na Zbořenci.

Na Zderaze is mentioned by Švejk in his long story about the big card-playing session. This was in connection with himself having been gambled away by Feldkurat Katz and therefore now became the servant of Oberleutnant Lukáš. The big winner in the card-playing anecdote, old tinsmith Vejvoda, lived in this street. The session took place in a pub behind Stoletá kavárna.

Na Zderaze appears again in [III.2] during a conversation between Švejk, Oberleutnant Lukáš and Offiziersdiener Baloun in Budapest. The good soldier tells a petrified Baloun that he had read in the papers that a whole family had been poisoned by liver paté there.

Background

Na Zderaze is a street in Nové město between Karlovo náměstí and Vltava. It stretches parallel to the river from Myslíkova ulice to Resslova ulice. Next to Stoletá kavárna and Na Zbořenci the street splits in two. The steet Na Zbořenci behind Stoletá kavárna was the likely location of the tavern where the famous game of cards took place.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.1] Na Zderaze žil nějakej klempíř Vejvoda a ten hrával vždy mariáš jedné hospodě za ,Stoletou kavárnou’.

[I.14.1] Kominickej mistr byl už do banku dlužen přes půl druhého milionu, uhlíř ze Zderazu asi milion, domovník ze ,Stoletý kavárny’ 800.000 korun, jeden medik přes dva miliony.

[I.14.1] Zabavili bank, vedli všechny na policii. Uhlíř ze Zderazu se zprotivil, tak ho přivezli v košatince.

[III.2] Já jsem čet několikrát v novinách, že se celá rodina votrávila játrovou paštikou. Jednou na Zderaze,jednou v Berouně, jednou v Táboře, jednou v Mladé Boleslavi, jednou v Příbrami.

Literature

| Myslíkova ulice |  | |||

| |||||

, 29.4.1909

Myslíkova ulice is mentioned in the anecdote about the great card-playing party in the pub behind Stoletá kavárna. Old tinsmith Vejvoda went to ask for help from the patrolling police in this street after winning to the extent that the other card players started to make it unpleasant for him.

Background

Myslíkova ulice is a street in Nové město that stretches from Spálená ulice down towards Vltava. One of the side streets is Na Zderaze.

Myslíkova ulice is a street Jaroslav Hašek would have known very well. Not only was it in the middle of his stomping ground in Praha II. - number 15 housed the editorial offices and print-works of Kopřivy (Nettles) and Právo lidu (The Peoples Right), publications of the Czechoslavic Social Democratic Labour Party. Hašek contributed frequently to both publications in 1913 and 1914.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.1] A jen tak bez klobouku vyběh na ulici a přímo do Myslíkovy ulice pro strážníky. Našel patrolu a oznámil jí, že v tej a tej hospodě hrajou hazardní hru.

Literature

- Stehlíkův historický a orientační průvodce ulicemi hlavního města Prahy, ,1929

- Můj přítel Hanuška, Jaroslav Hašek,5.10.1913

| Monte Carlo |  | |||

| |||||

,2.12.1910

Monte Carlo is mentioned in the anecdote about the great card-playing party of old tinsmith Vejvoda. The police inspector though this was worse than Monte Carlo.

Background

Monte Carlo is the most prosperous district of the Principality of Monaco and is best known for its casino that indirectly is referred to in the novel.

The districts road to fame started in 1863 when the current casino was completed. The same year the well known financier François Blanc (1806-1877), until then director of the casino in Bad Homburg, was hired to manage the casino. It still took many years before Monte Carlo became a household name for gambling, but by the outbreak of World War I it was already famous world wide.

In the manuscript Jaroslav Hašek spelt the name Monte Karlo but during a "clean-up" of The Good Soldier Švejk in the early 1950's, this and some other "oddities" were corrected. The inter-war issues of the novel, published by Adolf Synek, kept Hašek's original spelling.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.1] ,Tohle jsem ještě nežral,’ řekl policejní inspektor, když viděl takový závratný sumy, tohle je horší než Monte Karlo.

Also written:Monte KarloHašek

Literature

- Monte Carlo, ,2.4.1909

- The Magician of Monte Carlo, ,18.5.2011

| Chodov |  | |||

| |||||

Chodov, 1908

,1.1.1914

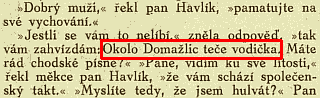

Chodov is mentioned in a song that Feldkurat Katz' new servant sings after considerable intake of strong drinks.

Background

Chodov is the name of four places in Bohemia, one on the outskirts of Prague and the three others in the west of the country. The text in the quote is picked from five different folk songs[a]. The first line is from a song from the Chodsko region near the border with Bavaria, so here it certainly refers to Chodov by Domažlice.

In 1913 Chodov belonged to hejtmanství Domažlice and the like-named okres. The population count was 1,947 and all but one were registered with Czech as their mother tongue. The community consisted of the villages Chodov, Trhanov and Pec.

Re-used text

The song-fragment from the book had already been used by Jaroslav Hašek. On New Years Day 1914 Kopřivy printed A story about a proper man but here the author uses Domažlice instead of Chodov.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Chodov had 1,947 inhabitants of whom 1,945 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Domažlice, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Domažlice.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Chodov were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 35 (Pilsen) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 7 (Pilsen).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.1] Švejk s novým mužem strávili noc příjemně vařením grogu. K ránu stál tlustý infanterista sotva na nohou a pobručoval si jen podivnou směs z různých národních písní, která se mu spletla dohromady:

Okolo Chodova teče vodička, šenkuje tam má milá pivečko červený. Horo, horo, vysoká jsi, šly panenky silnicí, na Bílé hoře sedláček oře.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:Meigelshofde

Literature

- Povídka o pořádnem člověku, Jaroslav Hašek,1.1.1914

- Historie obce Chodov, ,2017

- Okolo Chodova - směs českých lidových, [a]

| a | Okolo Chodova - směs českých lidových |

| Bílá Hora |  | |||

| |||||

Světozor, , 7.11.1913

Sokolský zpěvník, 1909

Bílá Hora is mention in the song Feldkurat Katz's new putzfleck sings after consuming solid quantities of strong drink.

Background

Bílá Hora (The White Mountain) is a hill on the western outskirts of Prague, between Smíchov, Břevnov and Ruzyně. Until 1922 it belonged to the village Řepy in hejtmanství and okres Smíchov, and in the ninteen-sixties it became part of the captial.

It is primarily known for the battle on 8 November 1620 that effectively ended Czech independence. Habsburg rule followed and lasted until 1918. The battle is regarded as one of the most important events of the Thirty Year War (1618-1648).

The text in the quote is picked from five different folk songs, also pointed out by the author himself. The line featured here is from the well known folk song "Na Bílé Hoře" (At White Mountain)[a]. See also Chodov.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Bílá Hora were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 28 (Prag) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 8 (Prag).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.1] Švejk s novým mužem strávili noc příjemně vařením grogu. K ránu stál tlustý infanterista sotva na nohou a pobručoval si jen podivnou směs z různých národních písní, která se mu spletla dohromady:

Okolo Chodova teče vodička, šenkuje tam má milá pivečko červený. Horo, horo, vysoká jsi, šly panenky silnicí, na Bílé hoře sedláček oře.

[II.3] My si sedneme naproti nim, jen jsme si überšvunky položili před sebe na stůl, a povídáme si: ,Vy pacholci, my vám dáme láňok,’ a nějakej Mejstřík, kerej měl ploutev jako Bílá hora, se hned nabíd, že si půjde zatančit a že nějakýmu syčákovi vezme holku z kola.

Credit: Jaroslav Šerák

Also written:The White MountainenDer Weiß BergdeDet kvite bergno

Literature

- Okolo Chodova - směs českých lidových, [a]

- Na Bílé Hoře,

- Bílá Hora a násilná protireformace katolická,

| a | Okolo Chodova - směs českých lidových |

| Toledo |  | |||

| |||||

Toledo en las fotos de Thomas (1884, 1910)

Světozor, , 13.1.1911

Toledo is mentioned as the Hertugen av duque Almavira is supposed to have eaten his servant Fernando during the siege of the city. In Budapest, Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek makes a similar reference, but the siege is now of Madrid and the Napoleonic wars are mentioned explicitly.

Background

Toledo is a historic city in Spain, 70 km south of Madrid. In 1986 the city was entered as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The city prospered in medieval times, and was for a while capital of Castilla. Today the city is capital of the Castilla-La Mancha region and a major tourist attraction.

The historical event in question could be from 930 to 932 when the city was encircled by the Moors during a Christian uprising. After a two year siege it surrendered due to hunger. A shorter siege took place in 1085 when the city was wrestled away from the Moors by Christians.

Jesús Carrobles Santos, "Historia de Toledo", 1997

Durante dos años se mantuvo el asedio a Toledo. Sus habitantes, como ya habían hecho en otras ocasiones, volvieron a solicitar ayuda militar cristiana, esta vez a Ramiro II. Pero el ejército que éste envió fue derrotado por las tropas omeyas. Aislados del exterior y acosados por el hambre, los toledanos tuvieron que rendirse. De esta manera, el 2 de agosto del 932, Abd al-Rahmán III entró a caballo en la ciudad donde estableció una numerosa guarnición, aunque no adoptó represalias ni medidas de castigo.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Našli bychom tam, že vévoda z Almaviru snědl svého vojenského sluhu při obležení Toleda z hladu bez soli..

Literature

| Swabia |  | |||

| |||||

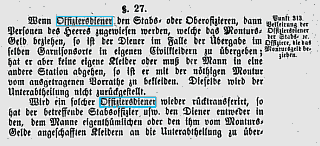

Leitfaden zur Manipulation bei den Unter-Abtheilungen der k.k. Landarmee, 1876

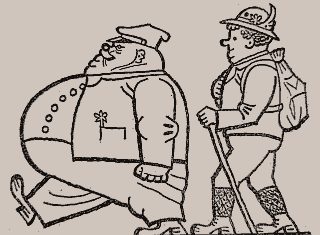

Swabia is indirectly mentioned by the author in the chapter about officer's servants. He mentions an old Swabian book about the art of warfare where it is described which personal traits an officer's servant is required to posses. It is not a small deal, he has to be a model human being.

Background

Swabia is a historical region in southern Germany that spans the borders of the current states Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. The principal cities in the area are Stuttgart, Ulm and Augsburg.

Type fonts

The author refers to an old Swabian book on the art of warfare, but it is not known what book he refers to. In Czech the expression švabach (Swabian writing) is often (imprecisely) used as a term for the old German type fonts (Frakturschrift) so the book is not necessarily of Swabian origin at all. At the author's time nearly all German-language newspaper and books used "Fraktur" fonts so he could in principle have referred to any old book in German about the art of waging war. The English translator of The Good Soldier Švejk, Cecil Parrott, evidently assumes this when he translates the phrase to "an old German book".

Jaroslav Hašek visited Swabia in 1904 and eventually wrote a few humorous stories from his travels here. Sjå Bavaria.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Ve staré švábské knize o umění vojenském nalézáme též pokyny pro vojenské sluhy. Pucflek staré doby měl býti zbožný, ctnostný, pravdomluvný, skromný, statečný, odvážný, poctivý, pracovitý. Zkrátka měl to být vzor člověka.

Also written:Švábskocz

Literature

- Přátelský zápas mezi Tillingen a Höchstädt, Jaroslav Hašek,10.7.1921

| Graz |  | |||

| |||||

Graz. Hauptplatz. Um 1910.

© IMAGNO/Austrian Archives

, 10.6.1912

Graz is mentioned by the author in the chapter about officer's servants. Here he recounts a trial in Graz in 1912 against a captain who had kicked his servant to death and had escaped without punishment "because it was only the second time he did it".

Graz is mentioned late in the novel in connection with Ratskeller.

Background

Graz is the second largest city on Austria and the capital of Styria. The city has appx. 250,000 inhabitants (2006). In 1910 the population counted almost 200,000.

Garrison city

Graz hosted the headquarters of 3. Armeekorps that recruited from Styria, all of current Slovenia and from smaller areas that is currently on Italian and Croat territory (Trieste og Istria). The recruitment districts with correspondingly numbered infantry regiments, were: 27 (Graz), 7 (Klagenfurt), 47 (Maribor), 17 (Ljubljana), 87 (Celje) and 97 (Trieste).

Officer's servants

It has not been possible to find a direct parallel to the case from 1912 about the captain who allegedly kicked his servant to death and was acquitted. Most probably the story is a product of the author's imagination and his tendency to grotesque exaggerations. That said the newspaper that year wrote about several other incidents where officer's servants were involved. There are reports about servants who stole from their officers, servants who committed suicide, and one servant who failed in an attempt to kill his superior and thereafter failed in killing himself.

An article in the Graz newspaper Arbeiterwille from 1912 deals with a case where an officer's servant commits suicide after being harassed over time and finally unjustly accused of having stolen five tins of conserves. The article also puts the tragedy in a greater perspective. It deals in more general terms with the hopeless situation of the army servant. He was obliged to serve not only his superior officer but also the family. If the situation became unbearable he couldn't simply quit his post as his civilian colleague could. The article advocates scrapping the whole institution of officer's servants, and moreover has certain parallels to the author's own description of the status of the officer's servant.

Concentration camp

During World War I Thalerhof by Graz was the site of the only concentration camp in the Austrian part of the Dual Empire (there were two in Hungary). See Steinhof.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Graz had 151 781 inhabitants.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Graz were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 27 (Graz) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 3 (Graz).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Roku 1912 byl ve Štyrském Hradci proces, při kterém vynikající úlohu hrál jeden hejtman, který ukopal svého pucfleka.

[IV.1] Všechny lidi, který potkával na ulici, viděl buď na nádraží v Miláně, nebo s nimi seděl ve Štýrským Hradci v radničním sklepě při víně.

Also written:Štýrský Hradeccz

Literature

- Revolveratentat eines Offiziersburschen genen einen Hauptmann, ,1.4.1912

- Diebstahl und Desertion, ,21.5.1912

- Tragisches Ende eines Offiziersdieners, ,10.6.1912

| Dubno |  | ||||

| ||||||

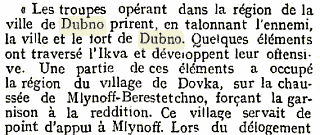

,13.4.1916

,12.6.1916

,13.6.1916

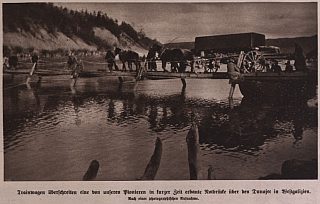

Dubno is mentioned when the author describes an officer's servant who was captured by the Russians. He dragged enormous amounts of luggage Dubno to Darnytsa and on to Tashkent where he pegged out from typhus on the top of the heap.

In the same section Hašek mentions "storming" Dubno which presumably refers to the events on 8 September 1915.

Background

Dubno (ukr. Дубно, rus. Дубно) is a city in the Volhynia province of Ukraine, until 1917 part of the Russian Volhynia governate. The city is located 15 km south of Chorupan where Jaroslav Hašek was captured on 24 September 1915. The area by Dubno had at the time a considerable number of Czech immigrants. See Zdolbunov.

Dubno was strategically important due to its fortress and the railway connections to the north and south. Austro-Hungarian forces entered the city on 8 September 1915 after an unexpected Russian withdrawal[a]. The latter re-conquered Dubno on 10 June 1916 during the Brusilov offensive[b].

Dubious claim

The city's web page claims that Jaroslav Hašek visited in 1915[c]. This seems improbable as Dubno was on Austrian hands at the time when the author was in the area. It is much more likely that he visited in 1916 and 1917 when the city was back in Russian hands and the author travelled in the aera, both as a reporter and from May 1917 as an ordinary soldier.

Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg, Band III

Schon am Vormittag 8.9.1915 langte beim 4. Armeekmdo. die überraschende Nachricht ein, daß Dubno vom Feinde preisgegeben sei und die Ikwabrücken bei der Stadt in Flammen stünden.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Viděl jsem jednoho zajatého důstojnického sluhu, který od Dubna šel s druhými pěšky až do Dárnice za Kyjevem.

[I.14.2] Dnes jsou důstojničtí sluhové roztroušení po celé naší republice a vypravují o svých hrdinných skutcích. Oni šturmovali Sokal, Dubno, Niš, Piavu.

Credit: Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg

Also written:ДубноruДубноua

Literature

- Історія міста, [c]

- Дубно,

- Ze životě našich krajanů v cízíně, ,5.3.1914

- Die Festung Dubno genommen, ,9.9.1915 [a]

- Från östra krigsskådeplatsen, ,13.6.1916 [b]

- U Dubna 1915, V. Mišner

| a | Die Festung Dubno genommen | 9.9.1915 | |

| b | Från östra krigsskådeplatsen | 13.6.1916 | |

| c | Історія міста |

| Darnytsa |  | ||||

| ||||||

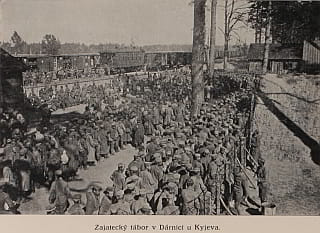

,1925

,1930

Elsa Brändström

,31.7.1932

Darnytsa is mentioned in connection with the officers servant who dragged his luggage from Dubno to Tashkent and in the end perished from typhus on top of the entire heap.

Background

Darnytsa (ukr. Дарниця) is today a district of Kyiv, east of the river Dniepr. Nowadays Darnytsa is a huge suburb, dominated by high-rise apartment blocks. There is a street named after Jaroslav Hašek here.

Darnytsa was a well-known transit camp that existed from 1915. In the beginning the camp was very primitive and lacked the most basic facilities. Diseases raged and mortality rates were scaringly high. The camp was also pivotal in supplying the Czech anti-Austrian volunteer forces, who from 1916 were allowed to recruit in Russian prisoner of war camps. See České legie.

Hašek and Darnica

According to Jaroslav Kejla the author was interned in the transit camp here for three days in the autumn of 1915, probably in early October[a]. From here he was sent onwards to Totskoye in southern Ural. His prisoner card has him registered in Penza on 6 October 1915. Kejla reports that the prisoners walked the 300 km from the Dubno-region to Darnytsa on foot on foot from 24 September, but this fits badly with Penza and 6 October. An explanation may be that the date is according the old Russian calendar, in which case the registration in Penza happened on 19 October.

There is also little doubt that Hašek revisited Darnytsa as a recruiter and agitator after he joined České legie in Kiev in July 1916.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Viděl jsem jednoho zajatého důstojnického sluhu, který od Dubna šel s druhými pěšky až do Dárnice za Kyjevem.

Credit: Jaroslav Kejla, Elsa Brändström

Also written:DárniceczDarnitsannДарницаruДарницяua

Literature

- Jak to bylo v bitvě u Chorupan kde se dal Jaroslav Hašek zajmout, ,1972 [a]

- Dárnica,

- Jak prý se vedlo Němcům v "českém zajetí" ..., ,10.5.1918

- Die tschecho-slawische Armee, ,20.9.1918

- Darnica - Kijev, ,1.9.1926

- Unter Kriegsgefangenen in Russland und Sibirien, Elsa Brandström,31.7.1932

- V Dárnici,

| a | Jak to bylo v bitvě u Chorupan kde se dal Jaroslav Hašek zajmout | 1972 |

| Kiev |  | ||||

| ||||||

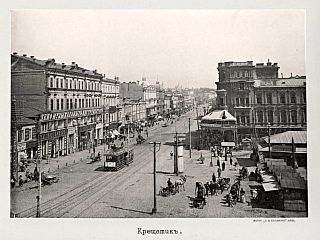

Saint Sophia square

,1925

,31.10.1917

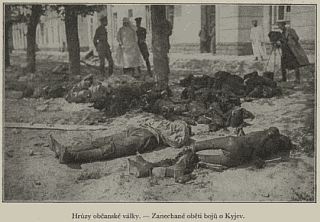

Horrors of the civil war - abandoned corpses after the fighting in Kiev (1918)

,1926

,23.3.1928

Kiev is mentioned 9 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Kiev is first mentioned when the author describes an officer's servant who was captured by the Russians. He dragged enormous amounts of luggage from Dubno to Darnytsa beyond Kiev and on to Tashkent where he pegged out from typhus on the top of the heap.

Soon after the city reappears when Švejk reads in a newspaper that "the commander of Przemyśl, general General Kusmanek, has arrived in Kiev".

During Švejk's stay in Przemyśl and his interrogation there, Kiev is mentioned no less than 7 times. Most of this occurs when a Polish informer-provoker is sent into Švejk's cell and tries to construct an incriminating story: that the two had met in Kiev.

Background

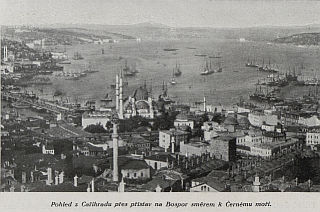

Kiev (ukr. Київ, rus. Киев) is the capital and largest city of Ukraine. It straddles both banks of the river Dnieper and has nearly 3 million inhabitants, making it the 7th largest city in Europe. The administrative centre and historic districts are located on the hills on the west bank.

Kiev was in 1914 capital of the Russian Kiev military district and "gubernia" of the same name. It had been under Russian control from the 17th century, although with a noticeable Polish footprint. The city also counted a large number of Jews.

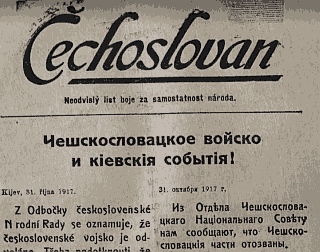

The city and the province had a sizeable Czech immigrant community and a Czech weekly Čechoslovan was published in Kiev until February 1918. During World War I the city was, together with Paris and Petrograd, the main centre of the Czechoslovak independence movement.

Turbulent times

Until the Russian October Revolution Kiev was relatively unaffected by the war apart from the general shortages and the fact that the city was the centre of the military assembly area and an important military-administrative centre. Kiev was also the headquarters of the Russian branch of the Czechoslovak National Council (see České legie). The leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, professor Professor Masaryk, stayed here for long periods between May 1917 and February 1918. It was in Kiev that he on 7 February 1918 signed the treaty of the transfer of the Legions from the Russian to the French army.

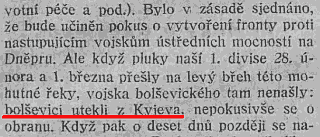

The Bolshevik coup in Petrograd on 7 November 1917 had far-reaching consequences for Kiev. Early in 1918 the Bolsheviks initiated military operations to gain control of Ukrainian territory, which at the time was partly controlled by the Tsentralna Rada (Central Council) of the Ukrainian National Republic. Red Guards led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko invaded the areas east of Dnieper, on 28 January they reached Kiev, and on 8 February 1918 the battle for the city was over.

The forces that entered Kiev were commanded by Mikhail A. Muravyov, a former officer in the Russian imperial army who was pivotal in defeating the forces of Kerensky who attempted to regain control of Petrograd during the October Revolution. He now acted as chief of staff for Antonov-Ovseyenko. He was a capable but brutal and megalomaniac officer. His deputy commander was Václav Fridrich, a former Czech legionnaire who had been expelled from the Legions for disciplinary reasons, and now as was imprisoned in Darnytsa, but set free by Muravyov's advancing troops. During the 10 day long siege of Kiev and ensuing occupation, a wave of terror, looting and killing followed. Muravyov later said that poison gas was used. Officers, members of the bourgeois and random inhabitants were slaughtered in their thousands. Muravyov and the atrocities of his troops became a liability for the Bolsheviks and he was transferred to the front against Romania on 28 February.

At the same time (9 February) Ukraine signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers. Professor Professor Masaryk who was staying in Kiev during this period, experienced the terror, but personally he got on well with Muravyov. With representatives for the Entente present, Masaryk and Muravyov reached an agreement that permitted the Legions to leave Ukraina unhindered and also to keep their weapons. According to Masaryk the deal was signed on 16 February.

The red reign of terror in Kiev didn't last long. On 18 February 1918 the Central Powers invaded Ukraine and already on 1 March German troops reached Kiev. The Red Guards and the Legions fled the city, and amongst those who escaped was Jaroslav Hašek.

Hašek in Kiev

Hotel Praha hosted the editorial offices of Čechoslovan

,23.4.1917

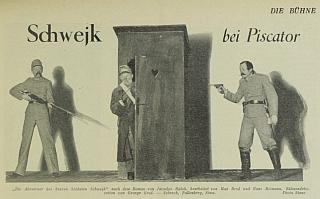

Thus Jaroslav Hašek witnessed those dramatic events in Kiev in February 1918. He had stayed for long periods in the city from 28 June 1916 [a] to May 1917 and again from 15 November until the end of February 1918. He was co-editor of Čechoslovan and also had duties involving recruitment and propaganda in prisoners camps. It was in Česchoslovan he wrote Povídka o obrázu císaře Františka Josefa I (The story of the picture of Emperor FJI) who led to a process "in absentia" of high treason back in Austria. Early in 1917 he published the second version of the "Soldier Švejk", Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí.

His time in Kiev was ridden with controversies: he was involved in a row with a Russian officer who he insulted and as a result ended up in prison. Soon after (early 1917) he was "deported" to the front and as a goodbye he published Klub českých Pickwiků (The Czech Pickwick Club) where he ridiculed some of the leaders of the Czechoslovak independence movement in Russia. From his "exile" at the front he was eventually forced to apologise in writing.

Hašek was recalled to Kiev on 15 November 1917 in order to testify against the alleged Austrian spy Alexander O. Mašek who he had earlier helped uncover. It was also in Kiev, during the first two months of 1918, that Jaroslav Hašek changed from being openly critical towards the Bolsheviks to openly sympathise with the new rulers in Petrograd. The reason for this turnaround are probably mixed but there is reason to believe that the young Communist Břetislav Hůla during this period had considerable influence on Hašek's political views. The two were both editors at Čechoslovan and travelled together to Moscow after their escape from Kiev. According to Václav Menger they were at the time very close (Václav Menger used the expression "inseparable").

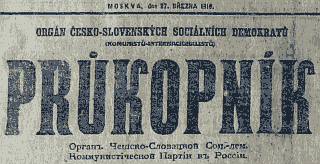

Important in understanding this shift is also that Hašek was firmly against transferring the Legions to France, and that they pulled out of Ukraine rather than fighting the Germans who were approaching Kiev. In a public meeting on 24 February he voiced his objections. He stated his point of view in detail in an article in Průkopník in Moscow on 27 March 1918. From Znal jsem Haška, Josef Pospíšil Proclamation from Václav Fridrich, Muravyov's chief of staff. ,12.2.1918.

Josef Pospíšil relates that Hašek met the leadership of the Bolshevik occupiers of Kiev in February. He was on friendly terms with them and recognised them as very capable people. That this positive personal impression may also have contributed to the author's radicalisation. Who these leaders were is not mentioned but it must be assumed that he met Fridrich (who he surely knew) and probably also Muravyov.

The occupants also took measures that Hašek probably approved of: price control (bread became cheaper), limit on bank transactions, nationalisation of the finance sector and a one time tax on rich citizens (contribution). Ironically enough the Bolsheviks also abolished capital punishment. In general the Czechoslovaks were on good terms with the revolutionary authorities. This was during February 1918 repeatedly stated by Československý deník, the official paper of the Czechoslovak National Council in Russia.

On the wall of the former Hotel Praha, the building that hosted the editorial offices of the paper, a memorial plaque honouring the author still hangs (2010).

General Kusmanek in Kiev

,28.3.1915

Finally back to the quote by Švejk about general General Kusmanek in Kiev. It is authentic and copied word by word from the press. This brief quote appeared in Národní politika 4 April 1915 and was also printed elsewhere. Newspapers also provided more comprehensive information. Kusmanek arrived in Kiev on an express train, first class, on 25 March. This was only three days after the capitulation of Przemyśl. He was very well treated in Kiev and even stayed as a guest of the governor. Furthermore his stay in Kiev was of a temporary nature, he was to be sent to the inner parts of Russia for permanent internment.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Viděl jsem jednoho zajatého důstojnického sluhu, který od Dubna šel s druhými pěšky až do Dárnice za Kyjevem.

[I.14.4] Švejk posadil se na lavici ve vratech a vykládal, že v bitevní frontě karpatské se útoky vojska ztroskotaly, na druhé straně však že velitel Přemyšlu, generál Kusmanek, přijel do Kyjeva a že za námi zůstalo v Srbsku jedenáct opěrných bodů a že Srbové dlouho nevydrží utíkat za našimi vojáky.

[IV.1] Major Wolf v té době ještě neměl zdání o tom, co vlastně všechno chystají Rakousku přeběhlíci, kteří později, setkávajíce se v Kyjevě a jinde, na otázku: „Co tady děláš?“ odpovídali vesele: „Zradil jsem císaře pána.“

[IV.1] Přihlásím se Rusům, že půjdu na forpatrolu ... Sloužil jsem u 6. kyjevské divise.

[IV.1] Já jsem v Kyjevě znal mnoho Čechů, kteří šli s námi na frontu, když jsme přešli do ruského vojska, nemůžu si teď ale vzpomenout na jejich jména a odkuď byli, snad ty si vzpomeneš na někoho, s kým si se tam tak stýkal, rád bych věděl, kdo tam je od našeho 28. regimentu?“

[IV.1] Zůstal tam zcela klidně a blábolil dále cosi o Kyjevu, a že Švejka tam rozhodně viděl, jak mašíroval mezi ruskými vojáky.

[IV.1] „Já znám vaše všechny známé z Kyjeva,“ neúnavně pokračoval zřízenec protišpionáže, „nebyl tam s vámi takový tlustý a jeden takový hubený? Teď nevím, jak se jmenovali a od kterého byli regimentu...“

[IV.1] Při odchodu řekla stvůra hlasitě k štábnímu šikovateli, ukazujíc na Švejka: „Je to můj starý kamarád z Kyjeva.“

[IV.1] Je zde přece úplné doznání obžalovaného, že se oblékl do ruské uniformy, potom jedno důležité svědectví, kde se přiznal obžalovaný, že byl v Kyjevě.

Credit: Viktor A. Savčenko, Josef Pospíšil, Pavel Gan, Radko Pytlík, Jaroslav Křížek, Tomáš Masaryk

Also written:KyjevczKiewdeКиевruКиївua

Literature

- Toulavé house, ,1971

- Jaroslav Hašek in der Ukraine 1917-18 …,

- Český patriot,

- Upomínky na můj vojenský život, ,2020 [a]

- Кто Вы, доктор Станко? – литературная гипотеза о Ярославе Гашеке в Киеве Подробнее,

- Красная гвардия. Как большевики впервые захватили Киев …, ,13.2.2015

- Главнокомандующий Муравьев: «... Наш лозунг — быть беспощадными!», ,2000

- Покоритель Киева, ,2019

- Red Guard: How the Bolsheviks seized Kyiv for the first time …, Chad Nagle,23.5.2015

- Klub českých Pikwiků, Jaroslav Hašek,23.4.1917J

- Den første fredsslutning, ,12.2.1918

- V Kyjevě 13. února, ,14.2.1918

- Z Kyjeva, ,16.2.1918G

- Boje o Kijev, ,17.2.1918G

- Als die Bolschewiken in Kiew herrschten, ,10.3.1918

- Jaroslav Hašek v legiích a proti nim, ,1.8.1937

- Vzpominka na T. G. Masaryka, Vincenc Svoboda,1937

- Jar. Hašek a legie: od zborovské bitvy až do odchodu, ,8.8.1937

- Ohlas Ríjnové revoluce v legiích, ,23.11.1967

| a | Upomínky na můj vojenský život | 2020 |

| Ukraine |  | |||

| |||||

The Cossack Hetmanate, 1654

,1888-

, 1907-1913

,20.8.1914

,12.12.1884

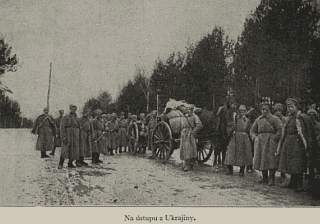

Ukraine is first mentioned when the author describes an officer's servant who was captured by the Russians. He dragged enormous amounts of luggage from Dubno to Darnytsa and on to Tashkent where he pegged out from typhus on the top of the heap.

At the very end of The Good Soldier Švejk the author touches on the relationship between Poles and Ukrainians, a conflict that had tragic consequences during World War II.

Background

Ukraine (ukr. Україна, rus. Украина) is a large and populous state in south west Europe with Kyiv as capital. The main language is Ukrainian but Russian is widely used, mainly in the east and in the south. Before World War I the name Ukraine had however a rather different meaning. According to Ottův slovník naučný (1888) it was a term that refers to "the south western part of Russia along the banks of the rivers Bug and Dnieper but which extent is not precisely defined". According to the encyclopaedia the name origins from the 17th century and means "borderland".

Meyers Konverzations-Lexikon uses approximately the same definition as Otto's Encyclopaedia but doesn't mention the river Bug; it rather states that Ukraine consists of the areas on both banks of the Dnieper. Nordic and English encyclopaedia from the time before World War I use more or less the same definition as Meyers.

The Hetmanate

The closest there was to an early Ukrainian nation state was the Hetmanate of the 17th century. It was founded through the rebellion of Bohdan Khmelnytsky against Polish supremacy, but he was dependent on help from abroad and ended up as a vassal of Moscow. The Hetmanate was historically important not only as a source of Ukrainian national identity, but it also started a process that gradually brought the Ukrainian lands under Russian control. This came at the expense of Poland and over time also the Ukrainians themselves.

The areas were thus mainly under Polish control until the 17th century, but at the peace treaty in Moscow in 1686 Poland was forced to cede the areas east of Dnieper and a smaller area around Kiev. Most of the west bank of the river only became Russian during Poland's second partition in 1793, and the rest during Poland's third partition in 1795. Galicia was ceded to Austria during Poland's first partition in 1772.

Little Russia

At the outbreak of war in 1914 Ukraine was a rather loosely defined geographical entity: it denoted the south-western part of the Tsarist empire. At the time the term Little Russia was far more commonly used, as witnessed by the entries in various encyclopaedia (amongst them Czech, Norwegian, Swedish, English and German). The term did not cover the Ukrainians part of the Dual Monarchy.

The Ukrainian language has roots at least back to the 13th century and national consciousness already existed but manifestations of nationalism were strongly suppressed by the Russian authorities. From 1804 Ukrainian was banned as a subject and as a language of teaching, a state of affairs that continued relatively unchanged until 1917. Literature and other publications written in Ukrainian were mostly published in Galicia, a region under Austrian rule. One of the victims of the Russian opression was the famous author Taras Shevchenko.

In The Good Soldier Švejk Jaroslav Hašek no doubt refers to Ukraine in accordance with the widely accepted definition of his time: as "the south-western regions of Russia".

Ruthenia

Ukrainians were recognised as a nation in Austria-Hungary and was commonly referred to as Ruthenians. In the Habsburg Empire their language and culture enjoyed far greater acceptance than in Russia. Ukrainian was one of twelve official languages and in 1918 there were 28 Ukrainian members of the lower chamber of the Austrian Reichsrat. This reflected their status as the fourth largest ethnic group in Cisleithania, behind Germans, Czechs and Poles. The Ukrainian territories of the Dual Empire extended across large parts of Galicia, eastern Slovakia, Carpathian Ruthenia and Bukovina.

The First World War

Already from the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 the war was conducted on Ukrainian soil, albeit in Galicia and Bukovina. In August 1915 the war was carried over to Russian-Ukrainian soil, and the front stretched across Russian-Ukrainian and Austrian-Ukrainian areas respectively until the summer of 1917 when the Russian army was forced out of the occupied territories once and for all.

In 1914 a considerable number of Czech immigrants lived in Ukraine, mostly in Kiev and Volhynia. It was in these circles that the seeds of what was to become České legie took root, and until March 1918 the Legions operated from Ukrainian soil.

Distrusted on both sides

Directive on taking hostages in Galicia

© ÖStA

Ukrainians were often distrusted by both parts in the conflict and not without reason. In Galicia and other Ukrainian areas of the Dual Monarchy there was widespread sympathy for Russia, a theme Hašek also mentions in the novel. Ukrainians together with Czechs were regarded the least trustworthy nation in Austria-Hungary, and already in 1914 there were built concentration camps for civilians where "Ruthenians" made up a large portion of the inmates. This was particularly the case in Thalerhof by Graz (see Steinhof). Many Ukrainian were summarily executed as "spies" and "collaborators" in the areas near the front.

It is documented that k.u.k. Heer took prominent "Russophile" citizens hostage when Galicia was reconquered in 1915, and threatened them with execution if sabotage took place in their area. In documents related to the 2nd Army this is clearly revealed, and on regimental level even our acquaintance Čeněk Sagner recommended in writing that suspect civilians be shown no mercy.

The conditions for Ukrainians in Russia during the war was probably not much better, but the information available is not that comprehensive. The pressure on Ukrainian language and culture had been somewhat eased from 1905, but was now intensified again. The well known nurse Elsa Brändström (aka. "the Siberian angel") wrote that "millions of Poles and Ukrainians were deported" and added that Jews were particularly targeted.

Revolution

The Chechoslovak army corps (Legions) pulling out of Ukraine in March 1918

In the aftermath of the October Revolution, Ukraine declared independence and took part in the peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk. On 9 February 1918 the treaty with the Central Powers was signed, but Kiev had already the previous day been occupied by Communist Red Guards commanded by colonel Mikhail Muravyov and a wave of terror ensued. These were events that Jaroslav Hašek personally witnessed.

On 18 February German forces invaded the now largely Bolshevik occupied Ukraine to force the revolutionary government in Russia to accept the peace terms. By the end of March all of Ukraine had been occupied, but the state formally continued to exists but now as a German puppet.

As a result of the post-World War I settlements the Ukrainian lands were split between the Soviet Union (where it was recognised as a political entity in the form of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic), Poland, Czechoslovakia and Romania.

Hašek in Ukraine

The only known photo of Jaroslav Hašek from the Russian part of Ukraine. Here with Jan Šípek and Václav Menger. Berezne, 29 September 1917 (12 October).

From July to September 1915 Jaroslav Hašek stayed on the territory of current Ukraine, as an Austrian soldier in Galicia and Volhynia. It was by Chorupan in Volhynia that the author was captured on 24 September 1915. From here the prisoners had to walk to the transit camp at Darnytsa (appx. 300 km) before they were transported onwards to camps in other parts of the Russian empire.

After having been released from the prisoner's camp in Totskoye in southern Ural, Hašek stayed in Ukraine from 28 June 1916 [a] until March 1918. During this time he worked for Czech organisations who were opposed to Austria-Hungary, units that were later to become known as Czechoslovak Legions (see České legie). He was predominately based in Kiev where he worked as an editor of Čechoslovan, but also travelled extensively between Kiev and the front. On 2 July 1917 he took part in the battle of Zborów where Czechs units for the first time fought against k.u.k. Heer.

Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911

UKRAINE (“frontier”), the name formerly given to a district of European Russia, now comprising the governments of Kharkov, Kiev, Podolia and Poltava. The portion east of the Dnieper became Russian in 1686 and the portion west of that river in 1793.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Nikdy nezapomenu toho člověka, který se tak mořil s tím přes celou Ukrajinu. Byl to živý špeditérský vůz a nemohu si vysvětlit, jak to mohl unést a táhnout kolik set kilometrů a potom jeti s tím až do Taškentu, opatrovat to a umřít na svých zavazadlech na skvrnitý tyf v zajateckém táboře.

Also written:UkrajinaczUkrainedeУкраинаruУкраїнаua

Literature

- Ukraine, ,1911

- Ukraine, ,1911

- Left-Bank Ukraine,

- Right-Bank Ukraine,

- History of Ukraine,

- Jaroslav Hašek in der Ukraine 1917-18 …,

- The Internment of Russophiles in Austria-Hungary, Serhiy Choliy,17.11.2020

- Ukraine, Liubov Zhvanko,8.10.2014

- Taras Hryhorovych Ševčenko, ,12.12.1884

- Den første fredsslutning, ,12.2.1918

- Boje o Kijev, ,17.2.1918J

- Upomínky na můj vojenský život, ,2020 [a]

- Ukrajina a ukrajinci, Dr. V. Charvát,1927

- Ukrajinci a jejich osvobozenecké hnutí, ,1928

| a | Upomínky na můj vojenský život | 2020 |

| Tashkent |  | |||

| |||||

,14.3.1917

From a Red Cross report, 1916.

Elsa Brändström: Amongst prisonsers of war in Russia and Siberia (1921)

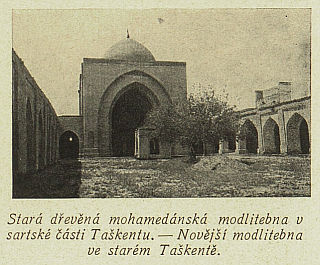

Tashkent is mentioned in the story the author tells about the officer's servant dragged a huge amount of luggage with him from Dubno, but who pegged out on top of his luggage in a prisoner's camp in Tashkent. He died from spotted typhus, a disease Jaroslav Hašek himself contracted in Russian captivity (but was somewhat luckier).

The city is mentioned amongst a number of places that don't at the time play a part in the plot, but that might have appeared again if Jaroslav Hašek had managed to complete the novel. See Sokal.

Background

Tashkent (rus. Ташкент) was in 1915 capital of the Russian general governorate Turkestan. It is now the capital of Uzbekistan after having been part of the Soviet Union until 1991. Today the city has more than 2 million inhabitants.

During the war there was a prisoner's camp in the city, and another one at Troytsky 30 kilometres from the centre. In both camps the inmates were mainly prisoners from the Slav nations of Austria-Hungary. Because many Czech were interned here Jaroslav Hašek surely knew a few people who had stories to tell from Tashkent.

Typhus

Typhus was a big problem in all the camps in Turkestan and in 1915 and 1916 epidemics raged. Health workers were inoculated but the prisoners rarely had this privilege. The casualties reached tens of thousands. Because many Czech were interned here Jaroslav Hašek surely knew a few people who had stories to tell from Tashkent.

In 1915 the Troytsky camp was ravaged by a severe epidemic, one of the worst that hit any of the Russian prisoners camps during the war. During three month 9,000 out of 17,000 prisoners perished. Otherwise the camp in the city was regarded as a good one, and the inmates enjoyed a large degree of freedom. Officers were allowed to leave the camp without an escort.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14] Nikdy nezapomenu toho člověka, který se tak mořil s tím přes celou Ukrajinu<. Byl to živý špeditérský vůz a nemohu si vysvětlit, jak to mohl unést a táhnout kolik set kilometrů a potom jeti s tím až do Taškentu, opatrovat to a umřít na svých zavazadlech na skvrnitý tyf v zajateckém táboře.

Credit: Elsa Brändström, F. Thormeyer, F. Ferrière

Also written:TaškentczTaschkentdeТашкентruToshkentuz

Literature

- Tyfové serum do turkestanských táborů zajatců, ,1.4.1916

- In die Gefangenschaft, ,23.4.1916

- První noc sederová, ,14.4.1933

- Documents guerre européenne, ,1916

| Sokal |  | ||||

| ||||||

View of the city from Sokal hora, 2010.

Sokal and Poturzyca on a k.u.k. military survey map.

,13.8.1914

,20.8.1914

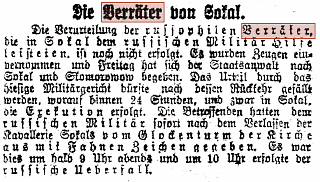

Sokal is mentioned 12 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Sokal (ukr. Сока́ль) is first mentioned by the author in a passage where he ironically describes how the officer servants ("Putzflecks") brag about their endeavours in various battles during the world war.

Sokal is one of a few places that appears in the chapter headers, here in [II.5]. In the content of the chapter Sokal is further mentioned by Oberst Schröder as he is about to show his fellow officers where the town is located on the map. In the end he sticks his finger in a turd that a tom-cat has been audacious enough to leave behind on the staff map.

In the next chapter [III.1] Sokal is mentioned again when Hauptmann Ságner receives an order by telegram at the station in Győr, "about quickly getting ready and set off for Sokal". The dispatcher is General Ritter von Herbert who has turned insane. At the station in Budapest [III.2] the battalion receives yet another nonsensical telegram from Herbert.

From Sanok [III.4] and until the end of the novel Sokal appears regularly, last in a conversation between Švejk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek where it transpires that "we are going Sokal". Marek tells Švejk that he is not going to get paid until after Sokal. Marek emphasised that it would be a useless undertaking to pay salaries to soldiers who are going to die anyway.

Beyond dispute is the fact that the author intended to place the plot at Sokal in the Part Four, a part that he never completed due to his premature death.

Background

Sokal is a regional capital in the Lviv oblast in western Ukraine. It is situated 80 km north of Lviv on the eastern bank of the Buh (Bug) and at present (2018) it has approximately 25,000 inhabitants.

From 1772 to 1918 the town belonged to Austria, in the inter-war period to Poland, after the Second World War to the Soviet Union and from 1991 to Ukraine. In 1881 the population was around 8,000 with a near equal distributions between Jews, Poles and Ukrainians. The town was situated approx. 10 km from the border with Russia.

Russian occupation

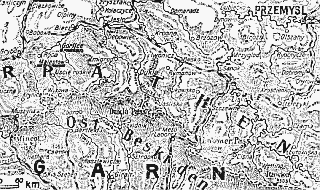

Sokal was soon after the outbreak of war attacked by Russian forces. Already 13 August 1914 the Russian general staff reported that the town had been captured, two bridges across the Bug blown up, provisions destroyed and the railway station torched. This news was however refuted by Austrian sources a few days later. These claim that the attack was a plundering mission and that the enemy had been repelled. Both Russian and Austrian reports confirm that the attack took place on 11 August, but the occupation was short-lived.

The Russians were however soon back. On 21 august the Austrians repelled another attack, but on 31 August Finnish newspapers reported that Sokal and several other towns and cities in Galicia had been captured.

In the aftermaths of the first Russian attack on Sokal, reports of treason against Austria-Hungary appeared in the newspapers. Some of the Emperor's Ruthenian (Ukrainian) subjects, 28 of them, were judged guilty as they allegedly had guided the Russians towards Sokal by signalling from church towers. They were from Skomorochy (ukr. Скоморохи) north of Sokal, and were sentenced to death on 20 August, and hanged in their home village the next day.

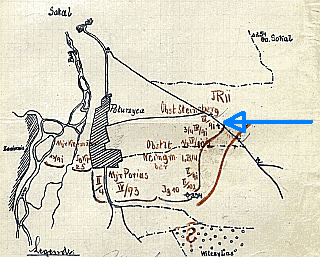

The Central Powers returning

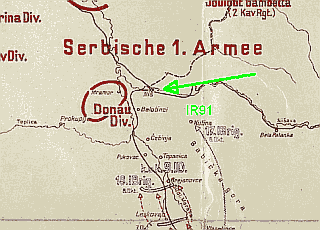

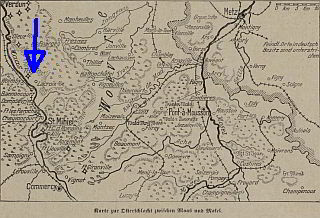

The situation south of Sokal on 27 July 1915. The blue arrow indicates the position of IR. 91, 11th field company.

© ÖStA

,29.7.1915

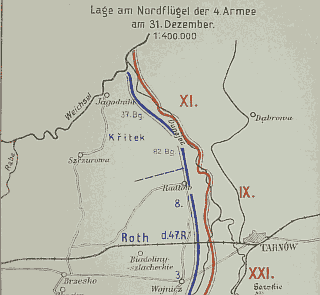

Sokal was reconquered by the Central Powers on 18 July 1915. For the remainder of the war the town was in Austrian hands and after the battle south of town during the next two weeks, Sokal disappears entirely from the news headlines.

The decisive battle over the control of Sokal took place from 15 to 31 July 1915. It started with an attack by k.u.k. 1. Armee, eventually supported by the German 103rd Infantry Division. They crossed the Bug and after fierce fighting they captured Sokal on the 18th. Thus k.u.k. Heer had established a bridgehead east of the river.

That same day there was however issued an order that had widespread consequences. The German commander-in-chief Mackesen ordered that 103rd Infantry Division and other German troops were to be pulled out to help general Linsingen further north. This put k.u.k. 1. Armee in a difficult situation, as the Russians, commanded by the competent general Brusilov, recaptured the hills south of Sokal on the 20th. From here they could shell the town and threaten to force the enemy back across the river.

Already the same day Paul Puhallo, commander of 1st Army, realised how serious the situation was. He asked for assistance and the request was granted. k.u.k. 2. Armee released the entire 9. Infanteriedivision (that Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 belonged to). According to the original plans they were to attack across the Bug by Kamionka Strumiłowa on 21 July, but in the night between the 20th and 21st they instead had to start marching northwards to relieve the threatened bridgehead at Sokal.

The order to move the division to this section of the front was thus the direct reason why Jaroslav Hašek got to Sokal at all, and hence leading to the town being mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk.

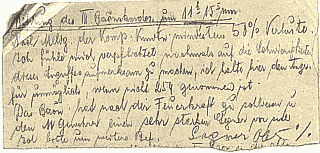

Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 by Sokal

Oberleutnant Sagner reporting on the critical situation of his battalion finds itself in. The losses are reaching at least 50 per cent.

© ÖStA

The regiment reached Opulsko west of Sokal on the 22nd and the next day they were in position by Poturzyca (ukr. Поториця), a few kilometres south of the town. At 4 PM on 25 July 1915 the signal for attack on the Russian positions on the hills by Poturzyca (Kote 254, 237, 234) was given. It was a brutal battle with frightening losses on both sides. It is estimated that 9. Infanteriedivision lost around half their men; killed, wounded and missing. On both sides a large number of prisoners were taken.

In the end k.u.k. Heer had to give up the attack and pull back to positions between Sokal and Poturzyca. They were actually saved by an unexpected Russian withdrawal that was caused by a German break-through further north. Thus the Russian forces by Sokal were in danger of getting trapped and were ordered to pull back. The gymnasium where parts of IR. 91 rested from 1 to 2 August 1915 © Daniel Abraham Bojiště u Sokalu ,25.9.1924

On 1 August the 9. Infanteriedivision was relieved. Parts of IR. 91 were lodged in the gymnasium in Sokal (Jan Vaněk mentions it in his diary), a fact that may have found its way into the novel but "relocated" to Sanok. In the evening of 2 August they started the march to the reserve positions by Żdżary, 15 kilometres north of Sokal. On 3 August, at 4 in the morning, the replacement had been completed. Żdżary was in an area that was infested by cholera, but it is not known whether anyone from the regiment were infected. 9. Infanteriedivision stayed in the area until 27 August when an offensive into Russia in the direction of Dubno started.

The original units from 1. Armee also took part in the battle. Amongst these were Infanterieregiment Nr. 4 (Hoch- und Deutschmeister from Vienna), Feldjägerbataillon Nr. 10 (Kopaljäger from Jihlava), Feldjägerbataillon Nr. 25 from Brno. These units had also taken part in the original conquest of Sokal, where particularly the Deutschmeister regiment distinguished itself.

Jaroslav Hašek and Sokal

Dekorierung at IR. 91/11. field company, Żdżary, on 18.8.1915. Colonel Rudolf Kießwetter handed out medals to the soldiers. On the photo, we can apart from Kießwetter himself, identify (a.o.) Vaněk, Hašek, Lukas and Sagner. From Bestand Rudolf Kießwetter.

© ÖStA

Jaroslav Hašek served as messenger in the III. Feldbataillon, 11. Feldkompanie. The battalion held one of the most exposed positions and suffered terrible losses. Still Čeněk Sagner led his unit commendably and in battle reports he was mentioned in very favourable terms. Oberleutnant Rudolf Lukas led F11. Kompanie, one of the four companies in Sagner's battalion.

Hašek was after the battle of Sokal promoted to Gefreiter and on 18 August 1915 he was decorated with a silver medal (2nd class) for bravery demonstrated during the fighting around Poturzyca on 25 July.

Several of the "models" for characters in The Good Soldier Švejk took part in the battle for Sokal: Rudolf Lukas, Čeněk Sagner, Hans Bigler, Jan Vaněk, František Strašlipka, Jan Eybl and Franz Wenzel.

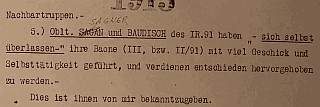

Apart from the author, Kadett Bigler and Oberleutnant Sagner were promoted after the battle. Oberleutnant Wenzel was investigated due to cowardly conduct. He allegedly left the command of his 2. battalion to Oberleutnant Peregrin Baudisch and for some mysterious reason spent time with the 4th battalion (who were reserves).

These were decorated after the battle: Jaroslav Hašek, Hans Bigler, Jan Vaněk, František Strašlipka and Čeněk Sagner. The latter was one of only three in the whole regiment who were given the highest recognition: the German "Eiserne Kreuz" (Iron Cross).

A well documented battle

From Jan Vaněk's diary. 31 July 1915.

From Gefechtsbericht, 9 August 1915. This report contains stinging criticism of how the main commanders of IR. 91 conducted the battle. Regimental commander Oberst Steinsberg and the commander of the 2nd battalion, Oberleutnant Wenzel, are singled out for particularly harsh criticism.

© ÖStA

Important testimonies of the battle are the diaries of Jan Vaněk and Jan Eybl, the notes of Bohumil Vlček, all from IR. 91. Moreover there is the diary of Eugen Hoeflich (better known as Moscheh Ya’akov Ben-Gavriêl) from Feldjägerbataillon Nr. 25, Brno.

Apart from these personal accounts, detailed descriptions of the battle can be found in the regimental chronicles of IR. 91, IR73 and IR102, probably also by Die Deutschmeister, Infanterieregiment Nr. 11 and others. Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg describes the battle thoroughly and gives insight into the decisions and considerations further up the command chain. In the war archives in Vienna and Prague there is more material that can be found; diaries, battle reports, orders, maps, photos and more. Material on IR. 91 and Sokal can be found in both archives.

Newspaper reports that mention Sokal were numerous, but on both sides the news stream was obviously filtered and censored. The respective setbacks were "wrapped in" or not mentioned at all, and own successes exaggerated. Much more informative are newspaper items from after the war, where individuals wrote about their experiences around Sokal.

The author of this web page has not found any eye-witness accounts from the Russian side, but official reports are available in Finnish newspapers (at the time Finland was a Russian Grand Duchy) and newspapers from neutral states like Norway, Sweden, Netherlands and Switzerland.

Hašek and the 300 prisoners

,24.2.1938

A sixteen-part series in Večerní České slovo from 1924, based partly on interviews with Rudolf Lukas, is also an important source. It has been much relied upon by post-World War II Haškologists. This despite a suspicion that the author of the series, Jan Morávek, "spiced up" his account to a considerable degree. One such case is the claim that Jaroslav Hašek was decorated because he convinced 300 Russians to give themselves up, and then led them to regiment HQ without disarming them, thus causing confusion and panic behind the lines.

This episode is not mention at all in the application for his decoration (Belohnungsantrag), but the story has many similarities with information from one of Rudolf Lukas's obituaries (Důjstonické listy, 24 February 1938). Here it transpires that Hašek actually was trusted by Lukas to lead a group of prisoners to positions behind the lines. Contrary to instructions he let them keep their weapons and this led to panic as they entered regiment HQ where the officers believed that the Russians had broken through. The episode put Lukas in a bad light but we don't know if it had any consequences for him.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Sokal had 11 610 inhabitants. The judicial district was Gerichtsbezirk Sokal, administratively it reported to Bezirkshauptmannschaft Sokal.

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Sokal were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 30 (Lemberg) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 19 (Lemberg).

Jan Vaněk

26.7.1915: Včera odpol přišel rozkaz „Ku předu“ na ruské zákopy. Nejdříve bombardovalo naše dělostřelectvo a pak jsme šli. Ale bylo to hrozné. Sotva naši lidé vyskočili na náspy, již se jich mnoho a mnoho válelo na zemi dílem mrtvých a raněných. Hrozná to byla hodinka. Postoupili jsme o 100 kroků do předu a dále to nešlo. Byli jsme seslabeni. K tomu ke všemu pršelo jen se lilo. Bláto zamazalo pušky, takže nebylo možno střílet. Trnuli jsme strachy a kdyby rusové udělali protiútok, že to nezadržíme. Ale nestalo se tak—do rána jsme se urželi a pak jsme pokračovali. Zajali jsme spousty Rusů.

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 auf Vormarsch in Galizien

28. juli 1915, 11 Uhr Nachts: Gleich darauf meldte Oberleutnant Sagner: Linker Flügel des III. Bataillons hat, da das Infanterieregiment Nr. 11 zurückgeging, jeden Anschluss verloren. Gegner durchgebrochen - Pionerabteilung des Regimentsreserven eingesetzt. Bitte um 2 Kompagnien an meinen linken Flügel da dieser in äusserst kritischer Situation ist.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Dnes jsou důstojničtí sluhové roztroušení po celé naší republice a vypravují o svých hrdinných skutcích. Oni šturmovali Sokal, Dubno, Niš, Piavu. Každý z nich je Napoleonem: „Povídal jsem našemu obrstovi, aby telefonoval do štábu, že už to může začít.“

[II.5] "Odtud, pánové, k Sokalu na Bug," řekl plukovník Schröder věštecky a posunul ukazováček po paměti ke Karpatům, přičemž zabořil jej do jedné z těch hromádek, jak se kocour staral udělat mapu bojiště plastickou.

[III.1] Telegram zněl prosté, nešifrován: "Rasch abkochen, dann Vormarsch nach Sokal." Hejtman Ságner povážlivé zakroutil hlavou. "Poslušné hlásím," řekl Matušič, "velitel stanice dá vás prosit k rozmluvě. Je tam ještě jeden telegram." Potom byla mezi velitelem nádraží a hejtmanem Ságnerem rozmluva velice důvěrného rázu. První telegram musel být odevzdán, třebas měl obsah velice překvapující, když je batalión na stanici v Rábu: "Rychle uvařit a pak pochodem na Sokal." Adresován byl nešifrovaně na pochodový batalión 91. pluku s kopií na pochodový batalión 75. pluku, který byl ještě vzadu. Podpis byl správný: Velitel brigády Ritter von Herbert.

[III.2] Matušič přinesl na vojenském nádraží v Budapešti hejtmanovi Ságnerovi z velitelství telegram, který poslal nešťastný velitel brigády dopravený do sanatoria. Byl téhož obsahu, nešifrován, jako na poslední stanici: "Rychle uvařit menáž a pochodem na Sokal." K tomu bylo připojeno: "Vozatajstvo začíslit u východní skupiny. Výzvědná služba se zrušuje. 13. pochodový prapor staví most přes řeku Bug. Bližší v novinách."

[III.4] Ačkoliv odtud bylo spojení železniční neporušeno pod Lvov i severně na Veliké Mosty, bylo vlastně záhadou, proč štáb východního úseku udělal tyto dispozice, aby železná brigáda se svým štábem soustřeďovala pochodové prapory sto padesát kilometrů v týlu, když šla v té době fronta od Brodů na Bug a podél řeky severně k Sokalu.

[III.4] Tato nešťastná kráva, možno-li vůbec nazvati onen přírodní zjev kravou, utkvěla všem účastníkům v živé paměti, a je téměř jisto, že kdyby později před bitvou u Sokalu byli velitelé připomněli mužstvu krávu z Liskowiec, že by se byla jedenáctá kumpanie za hrozného řevu vzteku vrhla s bajonetem na nepřítele.

[IV.1] Neznalo ještě nic určitého o revolučních organizacích v cizině a teprve v srpnu na linii Sokal Milijatin - Bubnovo obdrželi velitelé bataliónů důvěrné rezerváty, že bývalý rakouský profesor Masaryk utekl za hranice, kde vede proti Rakousku propagandu. Nějaký pitomeček od divize doplnil rezervát ještě tímto rozkazem: "V případě zachycení předvésti neprodlené k štábu divize!" Toto tedy připomínám panu presidentovi, aby věděl, jaké nástrahy a léčky byly na něho kladeny mezi Sokalem- Milijatinem a Bubnovou.

[IV.3] Major otevřel si stůl, vytáhl mapu a zamyslel se nad tím, že Felštýn je 40 kilometrů jihovýchodně od Přemyšlu, takže jevila se zde hrozná záhada, jak přišel pěšák Švejk k ruské uniformě v místech vzdálených přes sto padesát kilometrů od fronty, když pozice táhnou se v linii Sokal - Turze Kozlów.

[IV.3] "U nás ho teď nedostaneš, poněvadž my jdeme na Sokal a lénunk se bude vyplácet až po bitvě, musíme šetřit. Jestli počítám, že se to tam strhne za čtrnáct dní, tak se ušetří na každým padlým vojákovi i s culágama 24 K 72 hal."

Credit: VÚA, ÖStA, Milan Hodík, Bohumil Vlček, Jan Vaněk, Jan Ev. Eybl, Eugen Hoeflich

Also written:СокальruСокальua

Literature

- Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego..., ,1880 - 1914

- Сокаль,

- Family tree ->related pages ->Sokal,

- Wir standen bei Kirchbach im I. Korps., ,1926

- Die Deutschmeister, ,1928

- Carnage by Sokal, ,2010

- Jaroslav Hašek - dobrý voják Švejk, Jan Morávek,1924

- Připomínky k románu "Dobrého vojáka Švejka", ,20.3.1956

- Pouť feldkuráta Eybla světovou vojnou,

- Válečný deník Jana Vaňka, ,2014

- Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien, ,1927

- Die Eroberung von Sokal durch die k.u.k. 1. Armee (15. bis 18. Juli),

- Wechselvolles Ringen um den Brückenkopf bei Sokal (20. bis 31. Juli),

- Ryssarna tränt in på österrikistk område, ,13.8.1914

- Falsche russische Siegesmeldungen, ,17.8.1914

- 22 Bauern wegen Hochverrat zum Tode verurteilt, ,19.8.1914

- Události u Sokalu, ,19.8.1914

- Der Sieg bei Sokal, ,24.8.1914

- Dopis z boje u Sokalu, ,27.8.1914

- Boje o Sokal, ,14.8.1915

- Boje o Sokal, ,4.9.1915

- Zwei Tage in der Stellung der Deutschmeister, ,11.9.1915

- Die "grünen Teufel", ,27.4.1917

- Abschied des IV. Baons vom Inf. Regimente Nr. 91., Kießwetter Oberst,3.5.1918

- Svátek mrtvých v. r. 1915, ,8.11.1930

- Zemřel kamarád, ,24.2.1938

| Niš |  | |||

| |||||

Serbian funeral in Niš

© ÖStA

,7.11.1915

IR. 91 by Niš on 8 October 1918.

,1938

Niš is mentioned when the author riducules the officers' servants who "stormed" Niš, Sokal and Piave (and others).

Background

Niš (ser. Ниш) is a city in Serbia by the river Nišava. Counting more than 250,000 inhabitants it is the biggest city in southern Serbia and the third in the country behind Belgrade and Novi Sad.

During the war

The city was war-time capital of Serbia due to the exposed position of Belgrade at the border with Hungary. During the Central Power's offensive in the autumn of 1915 Niš was conquered by Bulgarian troops on 5 November 1915 after the Serbs had abandoned the city. It remained under Bulgarian occupation until 12 October 1918 when it was liberated by Serbian forces.

That Austrian soldiers would have been participating in the storming of Niš (as the author suggests) is unlikely as the operations against the city in 1915 were undertaken by the Bulgarian army.

IR. 91 by Niš

In late September 1918 Bulgaria pulled out of the war and left their allies on the Balkans dangerously exposed. 9. Infanteriedivision (including IR. 91) was therefore hastily transferred from the front by Piave to southern Serbia. The transport went by train via Udine, Ljubljana, Belgrade to Vranje on the Macedonian border. The division was seriously decimated and suffered from shortages and diseases. Some reserves didn't even have shoes. South of Vranje they immediately faced the advancing Serbian 1st Army and already on 3 October they had to withdraw northwards. The 17th Brigade (Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 and IR102) had a particularly arduous retreat across the mountains. On 8 October they had reached the vicinity of Niš and by 16 October had reached Vitkovač. The retreat continued northwards for the remaining few weeks of the war.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Oni šturmovali Sokal, Dubno, Niš, Piavu.

Credit: Jan Ciglbauer, Milan Hodík

Also written:NischdeНишsr

Literature

- Z Niše a okolí, ,12.11.1886

- Zur Kriegslage, ,9.11.1915

- De allieredes besættelse av Bulgarien, ,5.10.1918

- Aufbau einer neuen Front auf dem Balkan,

| Piave |  | |||

| |||||

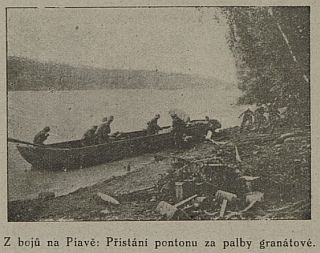

K.u.k. Heer crossing Piave by Grave di Papadopoli

Svět, 12.9.1918

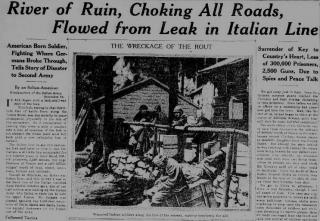

Piave is mentioned by the narrator when he ridicules the officers' servants who bragged about their exploits during the war.

Background

Piave is a river in northern Italy. It flows from the Alps and after 220 km ends in the Adriatic Sea near Venice.

During the war

After the Central Powers broke through by Caporetto 24 October 1917, Italian forces pulled back to the Piave where the front was stabilised in November after the enemy's attempt to cross the river failed. In June 1918 a second battle by the Piave took place. This was the last large-scale Austro-Hungarian operation in the war. The offensive failed and k.u.k. Wehrmacht suffered nearly 120,000 casualties. On 24 October 1918 the Allies attacked across the river and the Austro-Hungarian front collapsed.

By Piave a division of Czech legionnaires were fighting on the Italian side. Those who were captured were publicly executed. On one single day, 22 July 1918, no less than 160 legionnaires suffered this grim fate.

IR. 91 by Piave

During the offensive by Caporetto, IR. 91 followed k.u.k. Wehrmacht westwards from Isonzo to Piave where they arrived on 13 November 1917. For the first month they were stationed at Ponte di Piave, then moved on to Valdobbiadene further up the river.

During the failed Austrian offensive in the summer of 1918 they stayed in the reserve (15 to 23 June), were then moved down the river again to Grave di Papadopoli, a large island in Piave. Finally they were moved to the Serbian front, a transfer that began on 30 September. Amongst the models for characters in the novel only Hans Bigler served by Piave.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.2] Oni šturmovali Sokal, Dubno, Niš, Piavu.

Credit: Jan Ciglbauer, Milan Hodík

Also written:Piavacz

Literature

| South Bohemia |  | |||

| |||||

, 1897

, 1890

Ergänzungsbezirke Nr. 11, 91, 75

, 1911

South Bohemia is first mentioned when Hašek informs that Oberleutnant Lukáš hails from this region, in the author's own words "the Czech south".

I [I.15] is mentioned again when it is revealed that Oberst Kraus and his regiment got lost during manoeuvres here before the war.

South Bohemia is important in this novel since the plot of slightly more than two of the chapters is set here. Best known is Švejk's anabasis that provides a plethora of geographical references. The rest of the novel also contains details of places and people from the region. Švejk's IR. 91 was recruited from the area so the good soldier came across many people from the Czech south.

It even appears that the good soldier himself hails from the area (see Dražov), and it is directly stated that he did his compulsory military service in Budějovice and also took part in manoeuvres in the region. Amongst important literary figures from the Czech south we find Oberleutnant Lukáš and Offiziersdiener Baloun. Already in the first chapter of the novel South Bohemia is pulled in, see Břetislav Ludvík.

Background

South Bohemia is a vaguely defined geographical area that refers to the area that today roughly makes up Jihočeský kraj (the South Bohemian Region). Capital is České Budějovice, by far the largest city in the region. Amongst other noteable towns are Tábor, Písek, Strakonice, Krumlov, Třeboň, and Jindřichův Hradec. As an administrative entity it was created in 1949 as Budějovický kraj, and from 1960 it has the current name.

Military

Militarily the region reported to 8. Korpskommando and the following recruitment districts were fully or partially contained in this area: 11 (Písek, mostly), 75 (Jindřichův Hradec, mostly), 91 (Budějovice, fully) and 102 (Benešov, a small part).

Hašek and South Bohemia

That South Bohemia has such a prominent place in the novel is closely related to the author's own background. Even though Hašek was from Prague both parents were from the south, and already as a teenager he visited the region with his mother. An important impetus is also his grandfather Jareš, the pond warden from Krč, who told young Jaroslav many stories from the area.

In the end his father's birthplace strongly influenced what setting the author used for the novel from Part Two onwards. Because his father, Josef Hašek, was born in Mydlovary, his son also had Heimatrecht here. As Mydlovary was located in the recruitment district of IR. 91, Jaroslav Hašek was in 1915 called up to serve with this regiment, a fact that decidely influenced the direction of the plot, at least in a geographical sense.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.3] To bylo to, co zachoval z povahy sedláka na českém jihu, kde se narodil ve vesnici mezi černými lesy a rybníky.

[I.15] Nikdy nedorazil nikam včas, vodil pluk v kolonách proti strojním puškám a kdysi před lety stalo se při císařských manévrech na českém jihu, že se úplně s plukem ztratil, dostal se s ním až na Moravu, kde se s ním potloukal ještě několik dní po tom, když už bylo po manévrech a vojáci leželi v kasárnách.

Also written:Jižní ČechyczSüdböhmendeSør-Böhmennn

| Harz |  | ||||

| ||||||

,9.2.1913

,5.1.1908

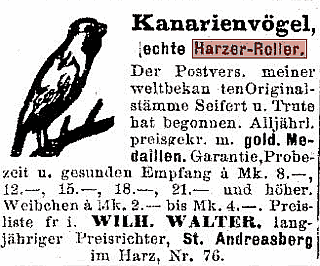

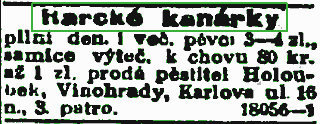

Harz is here used as an adjective in reference to a breed of canary birds; the Harzer Roller. The mentioned bird belonged to Oberleutnant Lukáš but suffered a grim fate as Švejk let the bird and the senior lieutenant's cat together "so they could get used to each other".

Background

Harz is a mountain range in Germany. It is the northernmost range in the country and straddles the borders of Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia.

Harzer Roller is a breed of canary birds that was bred in the Harz mountains and was very popular in the 19th century. It is best known as a singing bird but is also used in mines to warn against poisonous gases. It is particularly sensitive to carbon monoxide. The centre for breeding of this race is Sankt Andreasberg.

The breed regularly show up in newspaper adverts from before World War I, for instance in Národní politika. Jaroslav Hašek, who in 1909 and 1910 was editor of the animal magazine Svět zvířat, was very knowledgeable on animals, including birds.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.3] Neobyčejně rád měl zvířata. Měl harckého kanárka, angorskou kočku a stájového pinče.

Literature

| Canary Islands |  | |||

| |||||

Canary Islands is here used as an adjective in reference to a breed of birds that is named after these islands. Oberleutnant Lukáš was fond of animals and owned a Canary bird, a cat and a dog. The bird ended its life miserably as Švejk tried to let the bird and the cat get used to each other. The result is a foregone conclusion.

Background

Canary Islands is a group of islands in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Africa that belong to Spain.

The Canary bird is named after the Canary Islands where it lives in the wild. It is also present on the Azores and Madeira. It was imported to Europe as a domesticated animal, and in Central Europe it became particularly popular. During the 19th century the Harz region became the main centre of canary breeding.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.3] Neobyčejně rád měl zvířata. Měl harckého kanárka, angorskou kočku a stájového pinče.

[I.14.3] „Poslušně hlásím, pane obrlajtnant, že je vše v nejlepším pořádku, jedině kočka dělala neplechu a sežrala vašeho kanára.“

Also written:Kanárské ostrovyczKanarischen InselndeIslas Canariases

| Pelhřimov |  | |||

| |||||

© Pelhřimovský magazín

Pelhřimov is mentioned in a monologue where Švejk tells Oberleutnant Lukáš about a teacher teacher Marek from a village nearby who runs after the daughter of the game-keeper gamekeeper Špera.

The town is mentioned again when Švejk at a railway station in Vienna rejoins his obrlajtnant and immediately tells him about a certain Vaníček from Pelhřimov.

Background

Pelhřimov is a town in Vysočina with around 17,000 inhabitants (2010). It has a well preserved historic centre, and also a certain industrial tradition, for instance in brewing.

Demography

According to the 1910 census Pelhřimov had 5,738 inhabitants of whom 5,729 (99 per cent) reported using Czech in their daily speech. The judicial district was okres Pelhřimov, administratively it reported to hejtmanství Pelhřimov.

Source:Seznam míst v království Českém(1913)

Military

Per the recruitment districts, infantrymen from Pelhřimov were usually assigned to Infanterieregiment Nr. 75 (Neuhaus) or k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 29 (Budweis).

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.14.3] V jedný vesnici za Pelhřimovem byl nějaký učitel Marek a ten chodil za dcerou hajnýho Špery, a ten mu dal vzkázat, že jestli se bude s holkou scházet v lese, že mu, když ho potká, postí do zadnice z ručnice štětiny se solí.

[II.3] „Vostudu,“ pokračoval Švejk, „jsem vám jistě nikdy neudělal, jestli se něco stalo, to byla náhoda, pouhý řízení boží, jako říkal starej Vaníček z Pelhřimova, když si vodbejval šestatřicátej trest. Nikdy jsem nic neudělal naschvál, pane obrlajtnant, vždycky jsem chtěl udělat něco vobratnýho, dobrýho, a já za to nemůžu, jestli jsme voba z toho neměli žádnej profit a jenom samý pouhý trápení a mučení.“

Also written:Pilgramde

Literature

- Svíčková bába Albrechtová vykládá pohádku, proč nebyl za Pelhřimov zvolen farář Miloš Záruba, Jaroslav Hašek,17.3.1911

| Košíře |  | |||

| |||||

The Hlaváček tramway by Klamovka in June 1897

,17.11.1910

Košíře is mentioned in the dialogue between Oberleutnant Lukáš and Švejk after the cat has eaten the canary. This conversation touches on dog trade and falsification of pedigrees, and Švejk uses a mongrel from Košíře as an example.

In [I.15] the place is mentioned again in the anecdote about some Božetěch who made an income by stealing dogs and then claim rewards.

Background

Košíře is a district in Prague and is located in the western part of the capital, between Smíchov and Motol. Košíře was a separate town from 1895 until it joined greater Praha in 1922. As a curiosity should be mentioned the privatly owned tramway that connect the town with Smíchov centre.

Hašek in Košíře

Jaroslav Hašek officially lived in Košíře no. 908 from 4 February 1909. This was the address the editorial offices of the bi-weekly animal journal Svět zvířat, the journal where he for nearly two years functioned as an editor. The villa was situated above the Klamovka garden but was demolished some time between 2011 and 2015.

From 28 July 1910 shows him registered further down in the town towards Smíchov, in Košíře no. 1125. Here he lived with his wife Jarmila who he had married 23 May 1910. He stayed here (at least officially) until 28 December 1911 when he is recorded with residence Vršovice. It was from no. 1125 that he for a short period, at the end of 1910 and beginning of 1911, ran his unsuccessful "Kynological Institute", buying and selling dogs and other animals.

The birth of Švejk