Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

I. In the rear |

| |

2. The good soldier Švejk at police headquarters | |||

| C.k. policejní ředitelství |  | |||||

| Praha I./313, Ferdinandová třída 15 | |||||||

| |||||||

,13.9.1928

Like the author in the novel Břetislav Hůla (1950) mixes up the 3rd department with the State Police

,1911

C.k. policejní ředitelství was where was Švejk was led by detective Bretschneider after his arrest at U kalicha. He was accused of high treason, insulting His Majesty, and even sedition - accusations he agreed to without flinching. He stayed at police HQ through the whole of [I.2], a chapter which took place in the course of just one evening/night. In the morning he was taken to c.k. zemský co trestní soud in a police car which left through the main gate, i.e. in ul. Karoliny Světlé 2.

The gate of the building and three places inside are mentioned: the reception, the cells on the first floor and the interrogation room in the 3rd department, up the stairs from the cells but unclear on which floor. Švejk rarely complained, but here he shows his dissatisfaction with the long way from the cell to the interrogators room.

In [I.6] Švejk pays police HQ another visit after he was arrested because of his strikingly enthusiastic reaction to the declaration of war. Her the author delivers his personal opinion of the institution "where the spirit of foreign authority wafted through the building".

Background

C.k. policejní ředitelství (Police Headquarters) was the police HQ in Prague and it's official address in 1914 was Ferdinandova třída 15. The entrance was around the corner in ul. Karoliny Světlé 2. It was (and is) a huge complex, located between Ferdinandova, Karoliny Světlé and Bartolomejská. It is still (2018) the HQ of the Prague's police.

The Police HQ was organised in five departments where the State Police (Staatspolizei), department III (public order), and department IV (safety) are the ones that are relevant in the context of The Good Soldier Švejk. Department III is directly mentioned in the novel, although the author most probably has the State Police Department in mind. In 1913 the following of our acquaintances from the novel were employed: Mr. Slavíček and Mr. Klíma (State Police) and Polizeikommissar Drašner (department IV). Head of the 1st Department was Rudolf Demartini, a person who may have inspired Mr. Demartini, the fat gentleman at c.k. zemský co trestní soud.

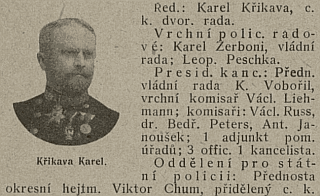

The head of c.k. policejní ředitelství carried the title "Police Director" (from 1912 "Police President") and the position was in the period 1902 to 1915 held by Court Councillor Karel Křikava, uncle of the writer Louis Křikava. He frequented the same environs as Hašek and is mentioned several times in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Head of the State Police Department was Viktor Chum.

Karel Křikava (1860 - 1935) made a rapid career in the police but was pensioned in 1915 for political reasons. He was not informed about the arrest of Kramář and as a result of the conflict that followed he was pensioned due to "health problems". After the war he was reactivated and was given the task of organising the police in Slovakia.

A Russian trader

In November 1915 Jaroslav Hašek acquired first hand knowledge of c.k. policejní ředitelství. As a premeditated provocation he registered at U Valšů as a Russian trader and the State Police soon arrived and arrested the "foreigner".

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In the second version of The Good Soldier Švejk (Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí), written by Jaroslav Hašek in 1917, police HQ is described in greater detail, particularly the department of Staatspolizei. Bartolomějská ulice is mentioned explicitly and so are the police commissioners Mr. Klíma and Mr. Slavíček and the author correctly notes that both worked for the state police. The description is more elaborate than in the novel and Chum is referred to as head of the "triumvirate".[1]

Švejka vedli k výslechu do oddělení státní policie přímo k policejnímu komisaři Klímovi a Slavíčkovi. Tito dva představitelé aparátu státní policie od vypuknutí války až po objevení Švejka v kanceláři vyšetřili několik set případů udání, provedli spoustu domovních prohlídek a odváděli muže od teplých večeří do Bartolomějské ulice. Jest zajímavé, proč department pražské státní policie právě se usadil v ulici připomínající svým jménem bartolomějskou noc …

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Sarajevský atentát naplnil policejní ředitelství četnými oběťmi. Vodili to jednoho po druhém a starý inspektor v přijímací kanceláři říkal svým dobráckým hlasem: „Von se vám ten Ferdinand nevyplatí!“ Když Švejka zavřeli v jedné z četných komor prvého patra, Švejk našel tam společnost šesti lidí.

[I.6] Budovou policejního ředitelství vanul duch cizí authority, která zjišťovala, jak dalece je obyvatelstvo nadšeno pro válku. Kromě několika výjimek, lidí, kteří nezapřeli, že jsou synové národa, který má vykrvácet za zájmy jemu úplně cizí, policejní ředitelství představovalo nejkrásnější skupiny byrokratických dravců, kteří měli smysl jedině pro žalář a šibenici, aby uhájili existenci zakroucených paragrafů.

[I.10.1] I on, Švejk, byl tenkrát v tom houfu, poněvadž při své smůle řekl komisaři Drašnerovi, když ho vyzval, aby se legitimoval: „Mají na to povolení od policejního ředitelství?“

[II.3] Jako jsem znal jednoho uhlíře, kerej byl se mnou zavřenej na začátku války na policejním ředitelství v Praze, nějakej František Škvor, pro velezrádu, a později snad taky vodpravenej kvůli nějakej pragmatickej sankci.

Also written:Police HeadquartersenPolizeidirektiondePolitihovudkvarteretno

Literature

- C.k. policejní ředitelství v Praze,

- Český antimilitarism, ,1922

- Rücktritt des Polizeipräsidenten Křikava, ,27.7.1915

- Právo lidu, ,7.8.1915

- Bašta germanisace, ,3.12.1917J

- Der erste Polizeipräsident von Prag gestorben, ,24.9.1935

- Pražské policejní ředitelství, jeho Státní(politická) policie a její informátoři …, Zdeněk Kárník

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| U Brejšky |  | ||||

| Praha II./107, Spálená ul. 47 | ||||||

| ||||||

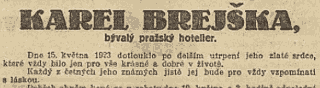

,15.5.1884

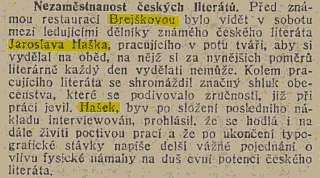

Breaking ice by U Brejšky. Jaroslav Hašek third from the left. Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj is in the middle. The tall man on the left is landlord Karel Brejška.

, 6.2.1914

,19.1.1914

Karel Brejška,1912.

© Národní archiv - Archiv České strany národně sociální

,17.5.1923

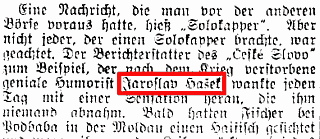

Egon Erwin Kisch

,6.12.1925

, 1925

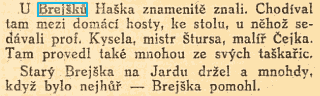

U Brejšky was where detective Brixi arrested an unusually fat owner of a paper shop who had bought beer for two Serbian students. The generous man was one of Švejk's inmates in the cell at c.k. policejní ředitelství. The pub is mentioned several times, and in the final chapter it crops up in an anecdote Švejk tells Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek. In this anecdote it is named U Brejsků, a minor change from singular to plural.

Background

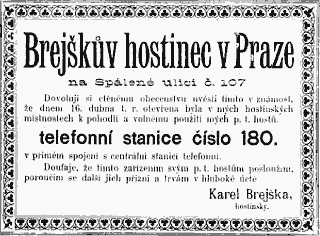

U Brejšky was a restaurant in Spalená ulice in Praha II. that in it's original form existed from 1884 until around 1920. It was known as a meeting place for journalists; Egon Erwin Kisch and others wrote about the phenomenon "news exchange" in Prager Tagblatt in 1925. Both Czech and German newspapermen frequented the place. Immediately after opening the restaurant had installed a telephone station (No. 180), a rare sight in 1884.

The restaurant served beer from Plzeň and was also known for its good food. Not only was it popular amongst journalists: visitors from the province also enjoyed it here. On the first floor it offered meeting rooms and accommodation. U Brejšky (aka. U Brejšků or Brejškova restaurace) was altogether one of the most best known and popular taverns in all of Prague, as indicated by the endless amount of newspaper clips. The restaurant was named after the original owner, Karel Brejška.

Jaroslav Hašek and Brejška

Hašek frequented it regularly and he mentions the restaurant not only in The Good Soldier Švejk but also in several of his short stories. Amongst them is Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí (1917) but here it occurs only briefly. On the other hand U Brejšky is the main focus of a story he wrote in 1912 about a meeting with the enormous black American Zipps. The landlord himself appears in the story and is described in positive terms.

U Brejšky is known from a photo where Jaroslav Hašek and Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj break ice on the street outside. A note in Právo lidu 19 January 1914 indicates that the picture was taken on 17 January 1914 and that it was published with a text on 6 February in Světozor. Both texts refer to a strike amongst typographers. In his memoirs Hájek wrote about Karel Brejška that the landlord liked Hašek and readily helped him when he was in trouble. Hájek incorrectly dates the picture to the winter of 1912, an error that later propagated into other literature about Hašek. Kuděj confirmed the information about the typographer's strike, that Brejška took pity on the two unemployed literates, and put them to work on writing menu's and breaking ice.

Karel Brejška

The owner of the restaurant was Karel Brejška (6 June 1856 - 15 May 1923), the big man seen to the left on the mentioned photo from Světozor. He bought the building Zlatá váha in Spalená ulice 117/47 for 60,000 guilders early in 1884. Prager Tagblatt reported that the restaurant operated from 19 January that year. Police records reveal that Brejška moved here in 1884, was married and had children. He was also a dedicated sportsman, above all in cycling, and readily took on duties. He edited the guest house owner's magazine Hostimil and hosted their editorial offices at U Brejšky. Karel Brejška was a popular figure and when he died after long illness in 1923, Eduard Bass, a friend of Jaroslav Hašek, wrote a long obituary in Lidové noviny[a]. They were not the only newspaper that fondly remembered him. Brejška sold the restaurant three years before he died.

Modern times

In 1939 was still listed in the address book but whether or not there has been continuous operation is not known. In any case it still exists in a modern variation (2016) with the name Haškova restaurace U Brejsků. It is decorated with photos from the era (many of them feature Hašek) and makes the most of its connection with him. Their web page say little about the historical lines. Instead it focuses on Hašek and the fact that the sports club Slavia was formed here on 31 May 1895. The current restaurant is located in the basement.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

The pub is also mentioned in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí. In the first chapter it is revealed that the court medics at c.k. zemský co trestní soud fetched breakfast here when they discussed Švejk's case and his striking eagerness to serve his emperor.[1]

Pak přinesli soudním lékařům od Brejšky snídani a lékaři při smažených kotletách se usnesli, že v případě Švejkově jde opravdu o těžký případ vleklé poruchy mysli.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Výjimku dělal neobyčejně tlustý pán s brýlemi, s uplakanýma očima, který byl zatčen doma ve svém bytě, poněvadž dva dny před atentátem v Sarajevu platil „U Brejšky“ za dva srbské studenty, techniky, útratu a detektivem Brixim byl spatřen v jejich společnosti opilý v „Montmartru“ v Řetězové ulici, kde, jak již v protokole potvrdil svým podpisem, též za ně platil.

Credit: Ladislav Hájek, Egon Erwin Kisch

Also written:Die ZecheReiner

Literature

- Jak jsem přemohl černošského obra Zippse ze Severní Ameriky, Jaroslav Hašek,3.5.1912

- Soupis pražských domovských příslušníků 1830-1910 (1920),

- Mitteilungen aus dem Publikum, ,19.1.1884

- Směna držebnosti, ,16.2.1884

- Brejškův hostinec v Praze, ,15.5.1884

- Brejškova restaurace, ,1886

- .. vyš. hpospodárské ústav ..,

- Brejška okraden, ,26.7.1913

- Následek sporu typografů se zaměstnavateli, ,6.2.1914

- Hádanka, ,22.10.1914

- Otec Brejška mrtev, ,17.5.1923 [a]

- Restaurateur Brejška gestorben, ,17.5.1923

- Karel Brejška zemřel, ,17.5.1923

- Die Börse der Nachrichten, ,6.12.1925

- Die Börse der Nachrichten, Egon Erwin Kisch,6.12.1925

- Z historie,

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| a | Otec Brejška mrtev | 17.5.1923 | |

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

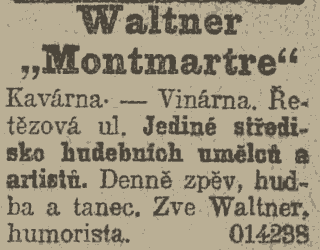

| Montmartre |  | ||||

| Praha I./224, Řetězová ul. 7 | ||||||

| ||||||

,2.9.1911

Montmartre is mentioned because the paper-shop owner who was Švejk's cell companion at c.k. policejní ředitelství had been observed drunk here together with the two Serbian students he had paid for earlier in the day, at U Brejšky.

Background

Montmartre was a café in the very centre of Prague that recently (as of 2010) was re-opened after a hiatus of 70 years. The name is obviously taken from the famous Paris district of Montmartre. The café is decorated with period photos where Jaroslav Hašek plays a prominent role. The 1989 Sametová revoluce put a stop to official plans to turn Montmartre into a museum dedicated to Jaroslav Hašek.

Montmartre was opened in 1911 by the well-known actor and artist Josef Waltner. It was a night café and entertainment establishment, also known as Cabaret Montmartre. From the beginning it became a popular meeting place amongst artists, intellectuals and the bohemian set. Apart from Jaroslav Hašek it was also frequented by the likes of Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj, Max Brod, Egon Erwin Kisch, Franz Werfel and Franz Kafka. Hašek wrote four short stories where Montmartre was involved, and Kisch also immortalised the café through his writing[a].

Egon Erwin Kisch

Und einer von ihnen hatte doch während jener Tagung noch die Habsburger geschützt, indem er dem Delegierten Jaroslav Hašek auf dessen Zwischenruf: "Borg mir eine Krone" ex praesidio die feierliche Rüge ersteilte: "Bitte die Krone nicht in die Debatte zu ziehen".

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Výjimku dělal neobyčejně tlustý pán s brýlemi, s uplakanýma očima, který byl zatčen doma ve svém bytě, poněvadž dva dny před atentátem v Sarajevu platil „U Brejšky“ za dva srbské studenty, techniky, útratu a detektivem Brixim byl spatřen v jejich společnosti opilý v „Montmartru“ v Řetězové ulici, kde, jak již v protokole potvrdil svým podpisem, též za ně platil.

Credit: Egon Erwin Kisch

Literature

- Románové restaurační a jiné zábavní podniky, ,2009 - 2021

- Montmartre, ,22.10.2023

- Černohorský jonák v úzkých, Jaroslav Hašek,1.8.1912

- Sen Josefa Waltnera, odvážného majitele kavárny Montmartre, Jaroslav Hašek,1915

- Můj zlatý dědeček, Jar. Hašek,1912

- Má tragedie montmartská, Jaroslav Hašek,1914

- Zitate vom Montmartre, [a]

- Der Letzte vom Prager Montmartre, Maxm. Huppert,14.8.1928

| a | Zitate vom Montmartre |

| Spolek Dobromil |  | ||||

| Podolí/55, Kublov | ||||||

| ||||||

Garden restaurant in Hodkovičky, a possible location for Dobromil's celebration.

Address book from 1910

Spolek Dobromil was a charity in Hodkovičky who held a celebration on the day of the murders in Sarajevo. The police arrived and asked them to stop, but the chairman retorted that hey had to finish playing "Hej, Slované" (well known pan-slavic hymn) first. This led him straight to the cell at c.k. policejní ředitelství.

Background

Spolek Dobromil is an association which so far has not been fully identified. It is still very likely that they existed and may well have congregated in the centre of Hodkovičky. In 1910 such a society existed in nearby Podolí and Dvorce, so it is quite likely that these are the people Jaroslav Hašek refers to.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Třetí spiklenec byl předseda dobročinného spolku „Dobromil“ v Hodkovičkách. V den, kdy byl spáchán atentát, pořádal „Dobromil“ zahradní slavnost spojenou s koncertem. Četnický strážmistr přišel, aby požádal účastníky, by se rozešli, že má Rakousko smutek, načež předseda „Dobromilu“ řekl dobrácky: „Počkají chvilku, než dohrajou ,Hej, Slované’.“

Credit: Milan Hodík

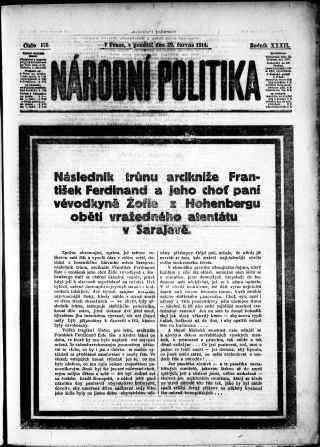

| Národní politika |  | ||||

| Praha II./835, Václavské nám. 21 | ||||||

| ||||||

,29.6.1914

,15.11.1915

Národní politika is first mentioned during the interrogation at c.k. policejní ředitelství when Švejk reveals that he reads the afternoon issue to look for dog adverts. He also uses the term "čubička" (the little bitch), which provokes the interrogator with the animal traits to shout: Out!.

Národní politika is mentioned again both in [I.6], [I.13] and in [II.2].

Background

Národní politika (National Politics) was a conservative daily that was published in Prague from 1883 to 1945. The editorial offices were located at Václavské náměstí. The paper printed at least six of Jaroslav Hašek's stories and it was one of the first papers to report both his capture in 1915 and his return to Prague (1920). In other stories he makes fun of the newspaper.

According to Franta Sauer it was the author's preferred newspaper, and at first sight it appears that he inserted snippets from it into The Good Soldier Švejk. The conversation between Oberleutnant Lukáš and hop trader Wendler in [I.14] reveals word for word quotes from the paper and the evening issue from 4 April 1915 is a prime example. That said, Kronika světové války is an even more obvious source for these fragments.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

In Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí is actually Národní politika the first institution that is mentioned. Here and in other official publications an arrest order from c.k. zemský co trestní soud regarding Švejk was printed.[1]

Tak daleko jsi to tedy dopracoval, můj dobrý vojáku Švejku! V Národní politice a jiných úředních věstnících objevilo se tvé jméno spojené s několika paragrafy trestního zákona.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] „S kýmpak se stýkáte?“ „Se svou posluhovačko, vašnosti.“ „A v místních politických kruzích nemáte nikoho známého?“ „To mám, vašnosti, kupuji si odpoledníčka „Národní politiky“, ,čubičky’.“ „Ven!“ zařval na Švejka pán se zvířecím vzezřením.

[I.6] posledně od toho pana řídícího z Brna ta záloha šedesát korun na angorskou kočku, kterou jste inseroval v Národní politice a místo toho jste mu poslal v bedničce od datlí to slepé štěňátko foxteriéra.

[I.13] Když tenkrát ta sopka Mont Pelé zničila celý ostrov Martinique, jeden profesor psal v Národní politice, že už dávno upozorňoval čtenáře na velkou skvrnu na slunci. A vona, ta Národní politika, včas nedošla na ten vostrov, a tak si to tam, na tom vostrově, vodskákali."

[II.2] I u nás jsou nadšenci. Četli v ,Národní politice’ o tom obrlajtnantovi Bergrovi od dělostřelectva, který si vylezl na vysokou jedli a zřídil si tam na větví beobachtungspunkt?

Also written:National PoliticsenNationalpolitikdeNasjonal Politikkno

Literature

- Písemnictví, ,4.4.1915

- Vánoce Národní politiky, Jaroslav Hašek,29.12.1907

- Malý oznamovatel Národní politiky, Jaroslav Hašek,8.2.1921

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| Museum |  | |||

| Praha II./1700, Václavské nám. 74 | |||||

| |||||

Světem letem, ,1896

Museum is mentioned in an anecdote by Švejk about quartering av prisoners in the bad old days. This is supposed to have happened on a hill somewhere by the museum. The museum itself is later mentioned explicitly in an anecdote on the way to Budapest.

Background

Museum which is talked about is certainly the main building of Museum království Českého, now Národní muzeum in Prague. It is located at the southern end of Václavské náměstí. The building was erected between 1885 and 1891.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

Museum is mentioned also in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí when is pushed to the draft board in a wheelchair.[1]

Lidé se smáli, přidávali se k zástupu a u Muzea dostal nějaký žid, který zvolal "Heil!", první ránu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[I.2] Takovejch případů bylo víc a ještě potom člověka čtvrtili nebo narazili na kůl někde u Musea

Literature

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

|

I. In the rear |

| |

2. The good soldier Švejk at police headquarters | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |