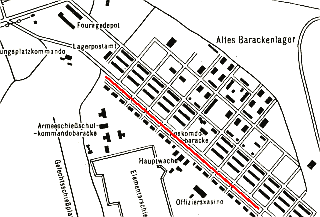

Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

II. At the front |

| |

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida | |||

| Lada |  | ||||

| Praha II./1733, Křemencová ul. 13 | ||||||

| ||||||

,15.12.1902

, 1910

Lada is briefly mentioned in Švejk's anecdote about negro Kristian. A female teacher wrote poems about shepherds and streams in the forest and published them in Lada. She also fornicated with an Abyssinian king and gave birth to the mentioned Kristian.

Background

Lada was a women's magazine that was published by Karel Vačlena in Mladá Boleslav with Věnceslava Lužická as its Prague-based editor[a]. It was published from 1889 to 1944 and a like-named magazine also appeared from 1861 to 1866. Whether there was a connection between the two is not known but in any case, Švejk definitely referred to the newer publication. In 1910 the magazine was published twice a month.

The magazine did print poems (at times even on the front page) but anything about shepherds and streams in the forest has not been found so far. At present (December 2021), only the year 1902 is publicly available.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Do toho se zamilovala jedna učitelka, která psala básničky do ,Lady’ vo pastejřích a potůčku v lese, šla s ním do hotelu a smilnila s ním. jak se říká v písmu svatým, a náramně se divila, že se jí narodil chlapeček úplně bílej.

Literature

| a | Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních | 1910 |

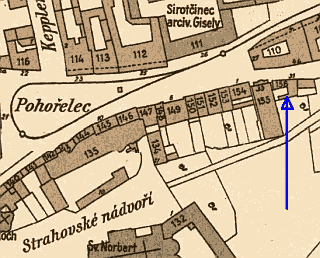

| Kateřinky |  | ||||

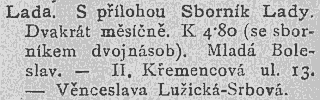

| Praha II./468, Kateřinská ul. 30 | ||||||

| ||||||

15.5.1906 • Pohled na vstupní portál domu čp. 468 v Kateřinské ulici na Novém Městě.

Kateřinky is mentioned in Švejk's story about negro Kristian. His mother was taken admitted to this asylum when she discovered that the dark skin of her son indeed was real.

It almost certainly the very institution where Švejk himself spent some time before the outbreak of war. See blázinec.

Background

Kateřinky was the colloquial name of a hospital for the mentally ill in Nové město. The official name was Královský český zemský ústav pro choromyslné v Praze, established in 1822[a]. It had subsidiaries at Na Slupi and Bohnice. These institutions still exist (2021).

Hašek at Kateřinky

Here Jaroslav Hašek spent some time in February 1911 after an apparent suicide attempt, where he tried to jump from Karlův most. Shortly after he was released he printed a story that in part seems related to this episode[b]. Nor is there any doubt that Hašek's stay here inspired the chapter on Švejk at blázinec.

It has been claimed that this suicide attempt was staged but the fact is that he was hospitalised on 9 February and left on the 27. Hašek actually asked to be allowed to stay at the asylum because he wanted to get rid of his alcohol habits. According to Radko Pytlík the incident was triggered by a domestic quarrel[c].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Tak se z toho pomátla, začala se ptát v časopisech o radu, co je proti mouřenínům, a vodvezli ji do Kateřinek a mouřenínka dali do sirotčince, kde z něho měli náramnou legraci.

Literature

- Řivnáčův Průvodce po Praze a okolí, ,1881 [a]

- Psychiatrická záhada, Jaroslav Hašek,24.4.1911 [b]

- Toulavé house, ,1971 [c]

- Zemské ústavy pro choromyslné v Čechách, ,1926

- Der Dichter des "Švejk" in Irrenhaus, ,10.9.1929

| a | Řivnáčův Průvodce po Praze a okolí | 1881 | |

| b | Psychiatrická záhada | Jaroslav Hašek | 24.4.1911 |

| c | Toulavé house | 1971 |

| Varieté |  | |||

| Karlín/283, Palackého tř. 6 | |||||

| |||||

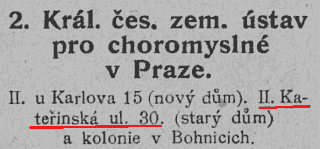

Praha moderní i historická ve 250 obrazech, ,1907

,18.4.1912

Průvodčí cizinců a jiné satiry z cest i domova, ,1913

Varieté is mentioned in Švejk's story about negro Kristian. Here it regards a case wehere a white lady unexpectedly gives birth to a black child. If this lady had been visiting Varieté on her own to watch a some negro in a game of wrestling one would certainly think certain thoughts.

Background

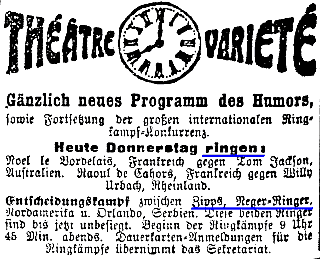

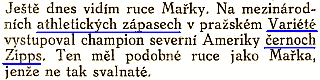

Varieté was the name of a theatre in Karlín that was opened in 1881. It is this one of the oldest theatres in Prague and is still operating, albeit with the name Karlín Music Theatre[a]. According to the address book from 1907 the official name was Théâtre Variété. Newspaper adverts reveal that they also arranged wrestling games[b].

Wrestling at Varieté

The thematic chain of Varieté-wrestling-negro is a re-use from two of Hašek's pre-war stories. Here the black wrestler is clearly identified as a North American champion with the surname Zipps[c][d]. This makes is straightforward to trace the inspiration for this sequence of The Good Soldier Švejk. In April 1912 Varieté arranged a major wrestling tournament and amongst the participants was the black wrestler Zipps [b].

Jak jsem přemohl černošského obra Zippse ze Severní Ameriky

Docílil snad vynálezce rádia Curie tak krásného výsledku, že německý zápasník Urbach položil se na lopatky za 5 minut? A dovolte ještě jednu otázku. Dostal někdy Svatopluk Čech do takového krásného mostu Skota Rankina, aby z toho mostu přehodil si onoho siláka přes rameno na zem, jako to udělal Zipps, ten šampión Severní Ameriky, o kterém mluvila celá Praha, když vystupoval v řeckořímských zápasech ve Varieté?

Machar si to velmi popletl s tou antickou kulturou. Nejsou to nějaké staré hrníčky, vykopané v Aténách a v Římě, ani básně starých Řeků a Římanů, synové Hélioví zanechali nám jiný, nehynoucí pomník, řeckořímské zápasy ve Varieté, kde z chumelenice hladkých těl vztyčuje se postava slavného zápasníka černocha Zippse, kterému jsem šlápl na kuří oko v Brejškově plzeňské restauraci.

Jaroslav Hašek, Dobrá kopa, 3.5.1912.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Ale najednou v nějakém kolenu že se vobjeví černoch. Představte si ten malér. Vy se voženíte s nějakou slečnou. Potvora je úplně bílá, a najednou vám porodí černocha. A jestli před devíti měsíci se šla podívat bez vás do Varieté na atletické zápasy, kde vystupoval nějakej černoch, tu myslím, že by vám to přeci jen trochu vrtalo hlavou.“

Literature

- Historie divadla, [a]

- Théâtre Variété, ,18.4.1912 [b]

- Jak jsem přemohl černošského obra Zippse ze Severní Ameriky, Jaroslav Hašek,3.5.1912 [c]

- Průvodčí cizinců a jiné satiry z cest i domova, ,1913 [d]

| a | Historie divadla | ||

| b | Théâtre Variété | 18.4.1912 | |

| c | Jak jsem přemohl černošského obra Zippse ze Severní Ameriky | Jaroslav Hašek | 3.5.1912 |

| d | Průvodčí cizinců a jiné satiry z cest i domova | 1913 |

| Pražské ledárny |  | |||

| Praha VII./862, Ostrov Velké Benátky - | |||||

| |||||

Branické ledárny s ledovým zálivem

,1.1.1913

,14.3.1912

Pražské ledárny is mentioned in the conversation between Švejk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek on the way from Mariánská kasárna to Budějovické nádraží. It regards Franz Joseph Land and deliveries to Prague's ice works.

Background

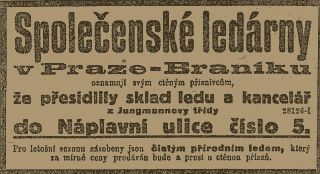

Pražské ledárny was a company that delivered ice to breweries, restaurants, hospitals, dairies, butchers and other enterprises that used ice for cooling purposes. To judge by newspaper adverts it was established in 1884[a] and was privately owned. Owner in 1892 was Ivan Čížek and in 1896 Bernard Lüftschitz is listed as owner. In both cases there were also other ownersdet. The ice works were from located at Štvanice island (also called Velké Benátky).

In 1898 the city had plans to build a new ice plant that was better able to satisfy the growing demand. The plans didnẗ materialise but in 1901 Lüftschitz sold his ice works[c] to a newly formed co-operative company named Společenské ledárny v Praze. It was owned by its customers and in 1908 they had 234 members[d], a number that by 1912 had grown to 299.

In Dolní Krč existed a rival enterprise owned by Tomáš Welz. In 1913 they two companies merged.

New plant

From 1909 to 1911 a new and bigger plant was constructed at Braník south of the city. The construction cost was however so high that the firm went bankrupt, but convertion to a limited company and investment of fresh capital saved it. The new company was registered in 1913 under the name Akciové ledárny v Praze[e]. In 1914 it reported a profit.

The company operated until 1954 and the building is still intact but in need of repair (2021). It was since 1964 been under heritage protection.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Podle statistiky je tam samý led a vyváží se odtud na ledoborcích patřících pražským ledárnám. Tento ledový průmysl je i cizinci neobyčejně ceněn a vážen, poněvadž je to podnik výnosný, ale nebezpečný.

Literature

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1892

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1896

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1910

- Sägespäne, ,12.1.1884 [a]

- Prager Eiswerke, ,12.7.1884

- Prager Eiswerke, ,1.11.1898 [b]

- Genoßenschafs-Eiswerke in Prag, ,23.1.1901 [c]

- Jak se děla led a v Praze na Vltavě zvláště, ,1.2.1907

- Společenské ledárny v Praze, ,29.2.1908 [d]

- Die Eiswerke in Branik, ,19.2.1911

- Společenské ledárny v Praze akciovou společností, ,22.2.1912

- Prazšké společenské ledárny, ,31.3.1912

- Konkurs, ,9.7.1912

- Ledárny, ,7.9.1912

- (Die Eiswerke in Branik), ,13.3.1913

- Nové české podniky, ,5.7.1913 [e]

| a | Sägespäne | 12.1.1884 | |

| b | Prager Eiswerke | 1.11.1898 | |

| c | Genoßenschafs-Eiswerke in Prag | 23.1.1901 | |

| d | Společenské ledárny v Praze | 29.2.1908 | |

| e | Nové české podniky | 5.7.1913 |

| K.k. Handelsministerium |  | |||

| Wien I., Postgasse 8 | |||||

| |||||

Nr. 10 (St. Barbara) und Nr. 8 (Handelsministerium).

,21.9.1912

K.k. Handelsministerium is mentioned in the conversation between Švejk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek on the way from Mariánská kasárna til Budějovické nádraží. The theme is supply of ice from Franz Joseph Land.

Background

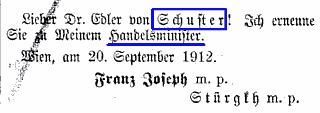

K.k. Handelsministerium (R.I. Trade Ministry) was the ministry of trade of Cisleithania and one of nine ministeries[1] in the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy. It was housed in Postgasse in the centre of Vienna. Secretary of trade from 20 September 1912 was Rudolf Schuster Edler von Bonott[a], an office he held until 30 November 1915[b].

The ministry of trade was one of the heavyweights of its kind in Cisleithania. Their areas of resposibility including trade, industry, the merchant fleet, mail, telephone, telegraph, customs, and from 1908 worker's welfare and social security[c].

1. Ministerium des/für Innern, Justiz, Unterricht, Finanz, Handel, öffentliche Arbeiten, Eisenbahn, Ackerbau, Landesverteidigung.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Nicméně úpravou klimatických poměrů, na které má velký zájem ministerstvo obchodu i zahraniční ministerstvo, je naděje, že budou náležitě využitkovány velké plochy ledovců.

Also written:R.I. Trade MinistryenC.k. ministerstvo obchoducz

Literature

- Amtlicher Teil, ,21.9.1912 [a]

- Amtlicher Teil, ,1.12.1915 [b]

- Grégrova příručka, ,1912 [c]

| a | Amtlicher Teil | 21.9.1912 | |

| b | Amtlicher Teil | 1.12.1915 | |

| c | Grégrova příručka | 1912 |

| K.u.k. Außenministerium |  | |||

| Wien I., Ballhausplatz 2 | |||||

| |||||

Ballhausplatz 2

,19.2.1912

K.u.k. Außenministerium is mentioned in the conversation between Švejk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek on the way from Mariánská kasárna til Budějovické nádraží. The theme is supply of ice from Franz Joseph Land.

Background

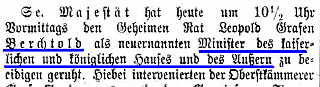

K.u.k. Außenministerium (I. and R. Foreign Ministry) (officilally k.u.k. Ministerium des kaiserlichen und königlichen Hauses und des Äußern) was the ministry of foreign affairs for the Dual Monarchy, one of thre three common ministeries (the others were k.u.k. Kriegsministerium and k.u.k. Finanzministerium). It was housed at Ballhausplatz by Hofburg in the centre of Vienna.

Secretary of foreign affairs from february 1912 was Count Leopold Berchtold, an office he held until January 1915. Berchtold played the dominant role in the decision-making process in Vienna that led to war in the summer of 1914[a], and it was he who drafted the 10 point ultimatum to Serbia. Berchtold was succeeded by István Burián.

Not only foreign affairs

As is evident from the full title of the ministry it was not only tasked with running foreign affairs in the classic sense (diplomacy, embassies, consulates, foreign policy etc.). It was even responsible for archives of the Imperial and Royal House (k.u.k. Haus, Hof und Staatsarchiv)[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Nicméně úpravou klimatických poměrů, na které má velký zájem ministerstvo obchodu i zahraniční ministerstvo, je naděje, že budou náležitě využitkovány velké plochy ledovců.

Also written:I. and R. Foreign MinistryenC. a k. zahraniční ministerstvocz

Literature

- Ministerium des Äußeren,

- Ballhausplatz, William D. Godsey [a]

- Grégrova příručka, ,1912 [b]

| a | Ballhausplatz | William D. Godsey | |

| b | Grégrova příručka | 1912 |

| K.k. Unterrichtsministerium |  | |||

| Wien I., Minoritenplatz 5 | |||||

| |||||

Palais des Unterrichtsministeriums

,4.11.1911

K.k. Unterrichtsministerium is one of three ministries mentioned by Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in the conversation between him, Švejk and the escort Korporal on the way from Mariánská kasárna til Budějovické nádraží. The theme is the supply of ice from Franz Joseph Land.

Background

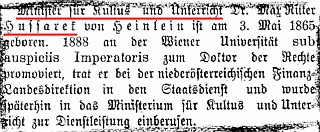

K.k. Unterrichtsministerium (I.R. Education Ministry) (officilally k.k. Ministerium für Kultus und Unterricht) was the ministry of culture and education for Cisleithania. It was housed at Minoritenplatz in the centre of Vienna.

Secretary of Education from 4 November 1911 was Max Hussarek von Henlein[a], a position he held until 1917.

Responsibilities

The ministry was responsible for education (apart from academies for trade, industry and agriculture), the Evangelical Church (Protestant), art, memorials, museums, science academies, meteorological institutes and son on[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] „Ministerstvo vyučování, pane kaprále, zbudovalo pro ně s velkým nákladem a obětmi, kdy zmrzlo pět stavitelů...“ „Zedníci se zachránili,“ přerušil ho Švejk, „poněvadž se vohřáli vod zapálený fajfky.“

Also written:I.R. Education MinistryenC.k. ministerstvo vyučovánícz

Literature

- Unterrichtsministerium,

- Inland, ,4.11.1911 [a]

- Grégrova příručka, ,1912 [b]

| a | Inland | 4.11.1911 | |

| b | Grégrova příručka | 1912 |

| Budějovický hotel (naproti nádraži) |  | |||

| |||||

, 30.7.1909

, 14.4.1909

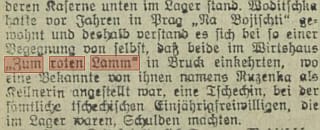

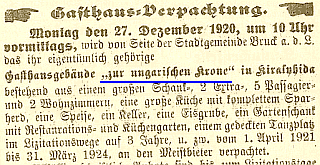

Budějovický hotel (naproti nádraži) (hotel opposite the station) is mentioned when the arrestees Švejk and Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek are escorted to Bud-Nad during the regiment's transfer from Budějovice to Bruck an der Leitha - Királyhida. From the windows of a hotel opposite the station, some ladies waved with handkerchiefs and shouted "Heil!".

Background

Budějovický hotel (naproti nádraži) refers to one of several hotels that were located around the railway station in Budějovice. Opposite the new station were situated Hotel Grand and Hotel Imperial, whereas opposite the old one were Hotel Bahnhof and Hotel Kaiser von Österreich[a]. Following the most direct route from Mariánská kasárna to Budějovické nádraží (the new station) the soldiers would first have arrived by Imperial but this hotel existed from 1924[b] so Grand remains as the obvious alternative. Nor should the two hotels by the old station be ruled out, but these were located further to the south so it is less likely that Hašek had one of these in mind.

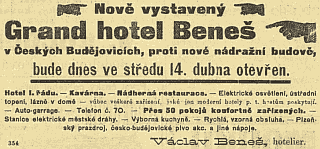

Grand Hotel Beneš

This hotel opened in 1909 and the owner was Václav Beneš (1860-), an experienced hotel owner who also had managed Hotel U třech kohoutů and Hotel Slunce på Budějovické náměstí [c]. Grand was the most modern hotel in the city, equipped with electric lighting, central heating and parking space for automobiles, which was very rare at the time.

Prominent guests often stayed here and one example is Feldmarschall-Leutnant Simon Schwerdtner (see Generalmajor von Schwarzburg) who slept at Grand when he inspected the garrison in Budějovice in April 1915[d]. Other guests were Archduke Joseph Ferdinand and Erzherzog Leopold Salvator from the house of Habsburg, noblemen Baron Alfred Rotschild and Duke Ernst August von Cumberland, moreover military notabilities like Andeas Pitlik, Wenzel Wurm and (Arthur Gieslingen).

In 1918 Beneš sold the hotel[e], in 1949 was nationalised and renamed Hotel Vltava, until it in 1989 again became Grand. Today (2022) there is still a hotel and restaurant operating in the building, but according to the reviews at Google the standard is poor.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.2] Byla to pořádná manifestace. Z hotelu naproti nádraží z oken mávaly nějaké dámy kapesníky a křičely „Heil!“ Do „nazdar“ mísilo se „heil“ i ze špalíru a nějakému nadšenci, který použil té příležitosti, aby vykřikl: „Nieder mit den Serben“, podrazili nohy a trochu po něm šlapali v umělé tlačenici.

Credit: Jan Schinko

Literature

- Hotel Grand,

- Hotely, [a]

- "Imperial" - bar a kavárna, ,31.10.1924 [b]

- Přezvetí hotelu, ,2.11.1908

- Grand Hotel "Beneš" v Čes. Budějovicích, ,20.8.1909

- Inspizierung, ,16.4.1915 [d]

- Hotelkauf, ,21.6.1918 [e]

- Hotelu Internacional se nedařilo, skončil po dvanácti letech, ,5.5.2016

- Původní majitel Grandu načasoval stavbu šikovně, ,1.6.2017 [c]

| a | Hotely | ||

| b | "Imperial" - bar a kavárna | 31.10.1924 | |

| c | Původní majitel Grandu načasoval stavbu šikovně | 1.6.2017 | |

| d | Inspizierung | 16.4.1915 | |

| e | Hotelkauf | 21.6.1918 |

| Kavalleriedivision Nr. 7 |  | ||||

| Kraków | ||||||

| ||||||

1914

GdK. Ignaz Edler von Korda

Unteilbar und Untrennbar, , 1917

,25.12.1915

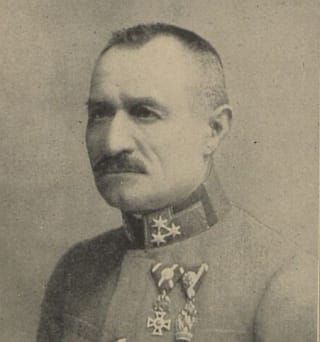

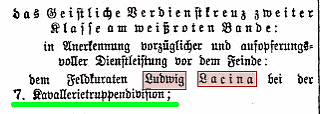

Kavalleriedivision Nr. 7 was according to the text of The Good Soldier Švejk the unit where Feldoberkurat Lacina served.

Background

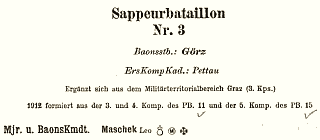

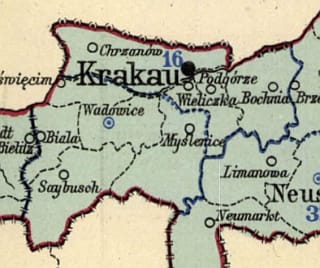

Kavalleriedivision Nr. 7 was a cavalry division headquartered in Kraków, reporting to the 1. Korpskommando. The four regiments of the division were scattered across a large area: Dragonerregiment Nr. 10 (Kraków), Ulanenregiment Nr. 2 (Tarnów), Dragonerregiment Nr. 12 (Olmütz) and Ulanenregiment Nr. 3 (Gródek Jagielloński). The division's commander in 1914 was Feldmarschall-Leutnant Ignaz von Korda (1858-1918)[a]. The exact address of the divisonal HQ is not known.

Ludvík Lacina

The direct reason why the division is mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk is that Ludvík Lacina, the model for Feldoberkurat Lacina was actually assigned to this unit from January 1913 to August 1916. That Jaroslav Hašek was aware of these details indicates that he knew Lacina personally.

Cavalry divisions

At the outbreak of war k.u.k. Heer contained eight cavalry divisions, numbered 1 to 10 where the numbers 5 and 9 were unused. The divisions were organised in one to three brigades. These usually consisted of to Ulan- Hussar- or Dragon-regiments. The cavalry brigades in Bohemia (Prague and Pardubice) were not assigned to any particular division[a].

During the war

From 6 August 1914 the division operated on Russian soil in the area around Kielce, north of Krákow. From May 1915 in the offensive in Russian Poland and in the autumn they operated by the river Styr (Стир) east of Lutsk (Луцьк) in current Ukraine. At the turn of the year, they were stationed by Brody. During the Brussilov offensive (from 4 June 1916) it suffered disastrous losses and was no longer of value as a fighting unit. After reinforcement and recuperation, they were in November 1916 moved to the new front against Romania.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Tak vešli na nádraží a šli k určenému vojenskému vlaku, když málem by byla ostrostřelecká kapela, jejíž kapelník byl vážně popleten nečekanou manifestací, spustila „Zachovej nám, Hospodine“. Naštěstí v pravé chvíli objevil se v černém tvrdém klobouku vrchní polní kurát páter Lacina od 7. jízdecké divise a počal dělat pořádek.

[II.3] Pohlcoval mísy s omáčkami a knedlíky, rval jako kočkovitá šelma maso od kostí a dostal se v kuchyni nakonec na rum, kterého když se nalokal, až krkal, vrátil se k večírku na rozloučenou, kde se proslavil novým chlastem. Měl v tom bohaté zkušenosti a u 7. jízdecké divise dopláceli vždy důstojníci na něho.

[II.3] Dostal nyní nový záchvat velkodušnosti a tvrdil, že všem udělá dobře, jednoročnímu dobrovolníkovi že koupí čokoládu, mužům z eskorty rum, desátníka že dá přeložit do fotografického oddělení při štábu 7. jízdní divize, že všechny osvobodí a že na ně nikdy nezapomene.

Literature

- Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 80), ,1914 [a]

| a | Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 80) | 1914 |

| 12. Kompanie |  | |||

| |||||

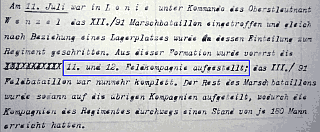

12. Feldkompanie reconstituted on 11.7.1915.

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien,1927

Some names from 12. Feldkompanie. These soldiers were decorated on 18.8.1915.

© VÚA/VHA

12. Kompanie is mentioned on the train from Budějovice to Bruck-Királyhida. The author remarked that the company consisted of Germans from Krumlovsko and Kašperské Hory.

In [IV.3] it is revealed that they were commanded by some Kompaniekomandant Zimmermann.

Background

12. Kompanie is not unambiguously identifiable but the numbering indicates that it was meant one of the 16 field companies of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. This assumption does however have a weakness. The plot at this stage takes place at the replacement battalion in Budějovice whereas the field companies had been fighting at the front since the start of the war. Thus one would assume that the company was an Ersatzkompanie or Marschkompanie. However, this is at odds with the fact that in 1915 these companies were never numbered as high as 12. The march battalions usually consisted of four companies and the reserve battalions rarely more than that.

This contradiction is rather a result of the author of The Good Soldier Švejk not bothering much about details like the numbering of military units and the logical connection between them. See also 11. Kompanie.

12. Feldkompanie

Throughout the novel Hašek consistently uses the numbering of field companies when he refers to "march companies" or simply "companies". This connection is particulalrly evident with the fictional "11th march company" where not only the number is borrowed from the corresponding field company but also the people in the command hierarchy (Rudolf Lukas, Čeněk Sagner). Thus there is every reason to assume that the same applies to 12. Kompanie. This company was one of four in III. Feldbataillon, the battalion that from 3 July 1915 was commanded by Sagner. The company commander from 11 July was Paul Kandl (1884-?), a reserve lieutenant from Prachatice[b] who propably arrived at the front with XII. Marschbataillon and surely was the commander of one of the battalion's four march companies. The 12th company was probably created directly from one of the four newly arrived march companies.

Jaroslav Kejla

Jaroslav Kejla who was taken prisoner together with Hašek on 24 September 1915 by Chorupan wrote about the four months he served with the company. As opposed to 11. Kompanie they were miserable catered for and parts of their rations were frequently stolen. The soldiers were dirty, exhausted, hungry, lice-ridden, and demoralised and during these four months, Kejla had a bath only once! He explained the difference between the 11th and the 12th company by the fact that the commander of the 11th company, Rudolf Lukas, was on friendly terms with battalion commander Čeněk Sagner and that his company, therefore, were better provided for[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.3] Teprve řev z vagonů vzadu přerušil vypravování Švejkovo. 12. kumpanie, kde byli samí Němci od Krumlovska a Kašperských Hor, hulákala: Wann ich kumm, wann ich kumm, wann ich wieda, wieda kumm.

Literature

- Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien, ,1927 [a]

- Jak to bylo v bitvě u Chorupan kde se dal Jaroslav Hašek zajmout, ,1972 [b]

| a | Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien | 1927 | |

| b | Jak to bylo v bitvě u Chorupan kde se dal Jaroslav Hašek zajmout | 1972 |

| Svět zvířat |  | ||||

| Smíchov/908, Bělohorská silnice | ||||||

| ||||||

No. 233: Probably the first issue that Jaroslav Hašek edited.

,15.2.1909

Víla Svět zvířat in 1903 or earlier.

Všecky druhy psů slovem i obrazem, ,1903

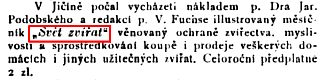

Svět zvířat is mentioned 11 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

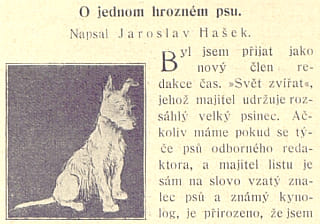

Svět zvířat (The Animal World) is the theme of the longest of all the numerous anecdotes in The Good Soldier Švejk, namely Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek's monologue in the prisoner's carriage on the way from Budějovice to Bruck-Királyhida. Here Marek relates in great detail about his experiences as an editor of this zoological magazine.

The story starts with Marek's friend Hájek being fired as editor by the magazine owner Fuchs after falling in love with his employer's daughter. Hájek was then tasked with finding a replacement and picked Marek who was subsequently interviewed for the post. He was questioned on his knowledge about animals, if he could cut and translate from foreign periodicals, translate from Brehm and his classic The Life of Animals, and how he envisaged the magazine's content going forward.

Marek answered that he in animals saw the transition from animal to human and that he also respected their wish to die as painlessly as possible before being eaten. He would introduce novelties like "Animals on Animals", "The Merry Animal's Corner", and "Movements among cattle". Fuchs was convinced enough to employ him and initially it proceeded smoothly. Still, after some time dark clouds began to gather above the head of the fresh editor...

The inventive Marek soon hit upon the idea that he ought to contribute more to zoology than the venerable Brehm had done in his "Life of Animals". The creatures from this book were after all well known and would thus be of little interest to the educated and inquisitive reader.

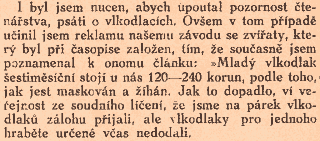

Out of thin air, he pulled creatures like the "sulphur-bellied whale", the "remote bat" from Iceland, Engineer Khún's Flea etc. This flea would eventually trip up Marek's career at the journal because it became the theme of a polemic between the newspapers Čech and Čas, where the latter swatted his flea by exposing the entire hoax. This incident, in addition to a heated debate with the editor of Selský obzor about the name of the jay eventually led to Marek being dismissed. The stress even caused Fuchs's premature death as he passed away three days after the final confrontation with his by-now-deposed editor.

Background

The magazine's origin, with an agenda of animal protection, hunting and purchase/sale of animals.

,1.10.1897

,15.2.1909

Svět zvířat (The Animal World) was an illustrated popular science magazine that specialised in animals and animal breeding that was established in Jičín by Jaroslav Podbodský (owner) and Václav Fuchs (publisher and chief editor). The first issue appeared on 1 September 1897 with a circulation of 10,000[j]. Already from the beginning, some well-known people wrote for the magazine, for instance the explorer Emil Holub.

In December 1898 Fuchs moved to a villa above the Klamovka gardens in Smíchov where he established the new editorial offices (by now he was by all evidence the sole proprietor). From 1901 onwards the magazine was issued twice a month and Fuchs established a kennel next to the villa (see Fuchsův psinec). In 1902 his wife Marie Fuchsová bought the villa for 22,400 crowns.

Chief editors were Václav Fuchs (1897-1911), Ladislav Hájek (1912-16, 1918-19), František Pober (1916-18,1920-22), Bohuslav Bayer (1917), and Karel Vika (1919)[t]. The best known co-editors were Karel Ladislav Kukla (1898-1906), Ladislav Hájek (1908-1909, 1910-1911) and, above all, Jaroslav Hašek (1909-1910, 1912-1913).

Václav Fuchs died in September 1911 and in 1912 the new owner Hájek relocated the editorial offices to the centre of Prague. The magazine continued to publish until 1922 when was renamed Život v přirodě, now with Svět zvířat as a supplement. An advert from 1925 reveals that the administration had moved back to the villa above Klamovka and was published weekly[2].

The annual subscription fee in 1910 was 10 crowns (13 crowns abroad), individual issues cost 50 hellers. The subscription prices had actually stayed the same since 1904! The magazine was published on the first and fifteenth every month, and publisher and chief editor was Václav Fuchs. The administration and editorial offices were located in the villa Svět zvířat above the Klamovka gardens in Smíchov and the journal was printed by Edvard Leschinger in Prague.

Staff

František Špirk was employed as an accountant and administrator in 1909 and also lived in the villa.

,1910

There exists no full overview of the staff during Hašek's time at Svět zvířat, apart from Václav Fuchs as owner, publisher and chief editor and Jaroslav Hašek as co-editor. If anyone else from the staff contributed to the journal is not known. One person that no doubt was associated with Fuchs' enterprise was Ladislav Čížek. As late as in 1957 a newspaper article provided more details, based on interviews with still living former staff. Apart from the mentioned Čížek Fuchs employed František Špirk as accountant and administratior and Josef Mikeš who dispatched parcels. A servant called Alois Ledecký also worked there[3].

Format and content

Classified adverts made up several pages.

,1.1.1910

In 1909 and 1910 each bi-weekly issue typically consisted of 24 pages. The first 2 and the last 9 mainly contained advertising and brief classified adverts. The remaining 13 pages carried animal-related material, written in a language comprehensible to everyman, interspersed with the odd advert. There is also a notable focus on animal welfare, particularly in the editorials and some of the in-depth articles.

In addition, the magazine published letters from readers, and entertainment in the shape of the column Veselý koutek (The Merry Corner). Further, each issue featured Svět rad (The World of Advice), Z celého světa (From Around the World). The World of Advice is probably based on Fuchs's book Všeobecný slovník rad pro každého (The General Dictionary of Advice for Everyone) (1906).

The Merry Corner predated Hašek's time at Svět zvířat with at least five years. ,15.1.1906

With nearly half the pages occupied by adverts, these were obviously an important source of income. Many adverts were for Fuchs' own journal and kennel, and even the enterprises of his brothers Diego and Evžen featured prominently. The classified minor adverts also played an important part. Under the headline Bursa zvířat (Animal Exchange) animals were advertised for purchase and sale, and many of the breeds mentioned in these adverts will strike a chord with readers of The Good Soldier Švejk.

Contributors

Fuchs, the owner and chief editor, wrote for the journal but his co-editor, be it Ladislav Hájek or Jaroslav Hašek, generally contributed more, at least to judge by the signed articles. Most entries were however unsigned and the shorter notices invariably so. Svět zvířat contained copious translated material, mostly of German origin, particularly from Brehms Tierleben (Brehm's Life of Animals).

The magazine contained many photos - mostly of animals but also of persons. Some of them feature people that the reader of The Good Soldier Švejk will recognize. Rittmeister Rotter, beekeeper Pazourek, Ladislav Hájek and Václav Fuchs are all pictured in the journal between 1909 and 1913. A considerable amount of the photos seem to have been cut from foreign magazines and books, again mostly German. In his article about in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona, Hašek claims that virtually everything was translated from German, and the photos invariably so. One example of a pure translation is the article Modern whale hunting that originally appeared in Über Land und Meer. Here not only the text but also some photos were copied. In the period before Hašek became editor the magazine also contained material of Polish, English and French origin, often translated by Karel Ladislav Kukla (1863-1930). Translated from German were also stories by fiction writers Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932) and Alexander Roda Roda (1872-1945).

Still, Hašek's claim that almost everything was translated is a gross exaggeration. As editors both Hašek, Hájek and Karel Ladislav Kukla wrote copious original material, so did Mařenka Fuchsová-Poberová (daughter of Fuchs). Other Czech contributors were the explorers Emil Holub and Alberto Vojtěch Frič, the poets Gustav Roger Opočenský and Adolf Heyduk, the writer Pavla Moudrá and the police officer Theodor Rotter. All co-editors (Kukla, Hájek and Hašek) were productive during their respective periods at the journal. The regular column about beekeeping was also Czech, mostly written by Karel Pazourek.

Hašek succeeds Hájek as editor

Hájek describes how Hašek betrayed him.

,1925

Early in 1908 the above-mentioned Hájek, one of Jaroslav Hašek's closest friends, was employed as editor of Svět zvířat. In the evening of the Vinohrady by-elections [s] (20 November 1908) he met Hašek in a pub, without a place to sleep and with wrecked shoes. Hájek offered his friend to stay with him in the villa above Klamovka. Hašek offered to help with the editorial work, he wanted to escape from the life he was currently living. Hašek wrote an item, was introduced to Fuchs, showed him what he had written and was offered a job, albeit with less pay than Hájek[a].

For some time the two friends worked together for Svět zvířat, but the situation was soon to change. Hájek, who was in love with the owner's daughter Žofie, felt that Fuchs pushed too hard to involve him in the family and in the business. Moreover, he was at odds with another employee. One day it boiled over, he had a row with his boss and handed in his resignation. He had hoped that Hašek would show solidarity and leave together with him but the "traitor" Hašek instead took over his job[a].

From 4 February 1909 until 28 July 1910 Hašek's registered domicile was Vila Svět zvířat. ,1851 - 1914

According to police registers Hašek lived in Vila Svět zvířat from 4 February 1909 until 28 July 1910[b]. Thereafter, he is registered at Smíchov No. 1125, below the Klamovka gardens, but within walking distance to the villa. Note that these are recorded dates and may not necessarily correspond to the actual dates he moved.

Hašek's first signed contribution. ,15.2.1909

One would thus assume that the change of editors happened in late January or early February 1909 and indeed on 15 February 1909 Hašek's first signed contribution appeared. Here the new editor describes his first encounter with the magazine. Václav Fuchs asked him to write an expert article on Chinese Pinschers (dogs) and Hašek described how he felt the weight of not being up to the task.

There is however an indication of a contribution already on 15 January. In this issue, there is a notice about the hippopotamus: "the Negroes caress baby hippos by blowing strongly up their nostrils"[o]. Hašek himself later claimed this as his hoax in a story he wrote after he had left the magazine[e] and for once there are good reasons to believe him. Still, it is astonishing that he dared such mischief at such an early stage! Hašek probably contributed also at the end of 1908, but this volume is yet to be investigated.

Permanently employed

Hašek's engagement with Svět zvířat was only the second time in his life that he was permanently employed, and now he lasted much longer in the job than he did at Banka Slavia, probably around 20 months. Fuchs was initially satisfied with his new employee, paid him decently, and the allowance even included two litres of beer a day! This way of rewarding the thirsty editor was simply a ploy to keep him on a short leash[a].

Officially stamped love letters

Letter to Jarmila, 10 July 1909

Information about his life above Klamovka can be found first-hand in his letters to his beloved Jarmila Mayerová who he had been courting since 1906. During the summer of 1909, she stayed in Přerov and letters between the two from this period have been preserved. Several of them are written on paper with the Svět zvířat letterhead, and some of them are even stamped!

In July 1909 Hašek complained to Jarmila about being overworked because Fuchs had gone away for a month, didn't write for the magazine at all, and left his understudy in charge of the enterprise. In addition, Hašek was busy running Fuchs' kennel, and evidently, he enjoyed working with animals, particularly his chimpanzee friend Julča who features in the journal several times, including on pictures. Hašek later wrote the story "My dear friend Julča"[k]. What he doesn't mention in the love letters is that he from 29 July to 3 August spent time behind bars due to a brawl at Bendlovka during some wild New Year celebrations.

Feathers flying

Hašek's mishap with the acorner.

,15.7.1909

During chief editor Fuchs's absence, his trusted understudy suffered a minor mishap, one that in a reshaped form found its way into The Good Soldier Švejk. On 15 July 1909 appeared in the Svět zvířat an item in a series of brief descriptions of animals[n]. This time it was the turn of the jay, and Hašek evidently translated these snippets from German, most probably from Brehm. In German the bird is called Eichelhäher (Garrulus glandarius), a name that indicates a connection to acorns (Eichel). This name stems from the fact that jays collect acorns and other nuts and store them as winter supplies. In Czech the word for acorn is žalud and Hašek translated Eichelhäher as žaludník whereas the correct term is sojka.

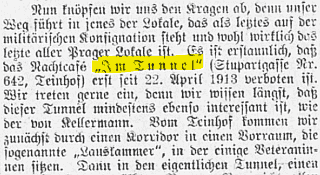

According to Radko Pytlík the editor of Selský obzor (Jos. M. Kadlčák) pointed out the error on a postcard to which Hašek responded impertinently. Kadlčák then complained in writing directly to Fuchs [k]. Hašek however stood his ground and published a response from a "reader" that also used the term "žaludník". Readers of The Good Soldier Švejk will recognise Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in this story, but on this occasion, Hašek's ornithological mishap had no immediate consequence. Through The Good Soldier Švejk and Marek's story Hašek thus transformed his translation mistake into conscious mystification.

Married

Hašek telling Jarmila about the conditions at the journal. The owner was about to leave for a month and left his understudy to manage the entire enterprise, including the kennel.

,10.7.1909

Hašek's improved financial situation, permanent employment and tidier lifestyle finally convinced Hašek's future parents-in-law that he was worthy of their daughter's hand and would be able to live an orderly life. In a letter dated 9 August 1909, Josefa Mayerová consented to the young couple getting married and Jarmila returned from Přerov soon after. From then on the correspondence between them paused but in March 1910 Hašek in a letter to his fiancee apologised for not being able to meet her that day. The reason was that he had to go on a business trip to Prague with Fuchs and he also told her that his employer had promised him a salary increase as soon as he got married (180 crowns per month).

On 23 May 1910, the couple finally married and they went on a short honeymoon to Motol. In the beginning Hašek was a model husband but in the end couldn't help being himself and started to stray around the pubs again. Not only did the return to his unruly lifestyle cause his wife pain but his appearances in the office became increasingly irregular[a].

Calamity

Hašek trying desperately to save his job.

,1925

Fuchs's initial enthusiasm had cooled due to Hašek often being absent and he had also been alarmed by reports that entries of dubious veracity appeared in his magazine and that readers had started to complain. Ladislav Hájek also relates that Hašek openly boasted to his friends about his past and ongoing "discoveries"! The exasperated Fuchs decided to get rid of Hašek, drove to Poděbrady and threatened Hájek that he would not be allowed to see his beloved Žofie unless he returned to take charge of the journal. A confrontation with Hašek took place and the latter claimed that everything that was printed had been translated correctly. Allegedly the only liberty he had taken was to substitute the names of some professors with those of his friends! Hájek noted that Hašek begged for mercy and was allowed to stay on but after about three months he decided to leave, complaining about poor pay[a].

The return of Hájek

With Ladislav Hájek becoming chief editor and eventual owner, the office was moved to Prague, and a new header was introduced.

,15.12.1912

Hašek's last story appeared on 15 October 1910 and Hájek was in charge again by the same time[c]. Hašek's dismissal from the magazine must have been a harsh blow to the newly wed couple, the young husband losing a well-paid job. Hájek even expresses regret that he inadvertently deprived his married friend of his job. In November 1910 Jaroslav and Jarmila set up their own dog trade but the enterprise collapsed almost immediately.

Václav Fuchs suddenly died in the autumn of 1911 and the kennel was taken over by František Pober, his son-in-law. Pober renamed the kennel Canisport, a term he had used for his previous dog business at Vinohrady. The editorial offices of Svět zvířat were eventually relocated to Hájek's flat at Ferdinandova třida no. 13 (now Narodní) in the city centre. This seems to have happened in October 1912 because the magazine header from now on stated "in Prague" and no longer "in Prague above Klamovka". Hájek had succeeded Fuchs as chief editor and later became the owner.

The 1911-1912 interlude and a pre-historic flea

Hašek's notorious flea

,1.9.1911

Even though Hašek from late 1910 onwards was no longer employed at Svět zvířat there is evidence that he from time to time contributed. On 15 May 1912, a report from a dog exhibition was signed Jaroslav Hašek and some weeks later a humorous story signed by Wilde was published (1 July). Based on a text analysis, Radko Pytlík concludes that it was written by Hašek. This is no surprise as one would assume that Hašek still was on good terms with his friend Hájek who was now chief editor and owner.

On the other hand, the timing of the "discovery" of Engineer Khún's Flea, an unsigned notice in the column "From Around the World"[*], is very strange. It was printed around 10 months after Hašek left Svět zvířat. At this time Fuchs was still alive and functioning as chief editor with Ladislav Hájek as co-editor. Scholars have not identified any contributions by Hašek in 1911, but this entry proves the opposite. In addition to his famous flea, he may have provided other minor items. This subject needs further investigation and seems to have escaped Radko Pytlík and other experts. On the same date another entry that the editors of Malá zoologická zahrada assumed to be by Hašek was printed, but this story had already appeared in Plzenské listy and was surely not the work of the famous prankster. A plausible theory, suggested by Jaroslav Šerák, is that Hájek may have been in on the joke. Otherwise, it is difficult to explain how the flea could have found its way there.

Hašek pardoned

Christmas night in the forest, Hašek back as editor.

,15.12.1912

Towards the end of 1912, Hašek was again invited to stay with Ladislav Hájek who was now married to Fuchs' daughter Žofie. And like in November 1908 it was a "rescue operation" that brought him under the same roof as Hájek. And history repeated itself. Hašek duly promised to help with the editorial work and also declared that his little jokes from the past would not occur again! In the beginning, the undertaking proceeded smoothly and before Christmas Hašek wrote a run-of-the-mill story. But soon he started to drift around the pubs and neglected his duties at Svět zvířat [a]. On 15 May 1913, his last ever signed contribution was published. During his second period at the journal, there were no obvious hoaxes (apart from a few April Fool's jokes) and Hašek himself didn't write any short stories that refer to this shorter assignment at Svět zvířat.

Hašek's contributions

Some mysteries from prehistoric times.

,15.8.1910

It is impossible to know exactly how many stories and other items Hašek wrote for Svět zvířat. According to the most up to date bibliography[d] eighteen stories and articles are signed in full by Hašek and another nine with pseudonyms assumed to be his. The pseudonyms are: Frant. Winter, dr. Th. Zell, A.K, Dr. Vilém Stanko, Milka Langorvá, Jos. Pexider, Vladimír Mayer, Wilde, J.H.. Finally, eight stories are unsigned but believed to have been written by Hašek, based on text analysis.

Four items in the categories pseudonyms and unsigned are marked with "debatable authorship" and may be mere translations. This number can now (October 2024) be reduced to two as it has been revealed that dr. Th. Zell and Frant. Winter are not pseudonyms and that the corresponding items are translations from German. Theodor Zell was a well-known German zoologist and many of his articles were appeared in Svět zvířat in 1907 and 1908. Franz Winter wrote an article about modern whale hunting in Über Land und Meer that was translated and published in Svět zvířat.

In addition, there are numerous brief items that one assumes Hašek wrote or translated. The bulk of these were identified by Zdena Ančík, Milan Jankovič, and Radko Pytlík and are included in the compilation The Entertaining and Educational Corner of Jaroslav Hašek[q]. Hašek surely wrote more than 100 large and small entries but the exact number is impossible to ascertain.

Some curiosities from the kingdom of animals, here the hippo. This entry is one of only a handful of verified pranks by Hašek: The negros cuddle young hippos by blowing strongly up their nostrils. ,15.1.1909

On 1 January 1909, the series Některé zajímavosti z říše zvířat, sestavené dle abecedního pořádku (Some curiosities from the kingdom of animals, compiled in alphabetical order) was introduced and this more or less coincides with Hašek's starting to contribute to the journal. One must assume that he wrote all these entries. The cycle featured in 15 issues of Svět zvířat, running until 15 August 1909 (with one gap). Altogether the series contains descriptions of 84 breeds, starting with the Amazon parrot and ending with the zebra.

The number of entries in each bi-weekly issue of Svět zvířat was as follows: 18, 4, 4, 4, 5, 5, 6, 5, 4, 7, 4, 2, 4, 3, 4, 0, 5. The series was introduced by aplomb in the first issue (18 animals) but the numbers soon dwindled to an average of 4 to 5. Nor was it always in alphabetical order and animals from the letter range O to S are missing altogether. The otter (vydra) and polecat (tchoř) even feature twice, albeit with differing descriptions.

In the summer of 1909 Fuchs went on holiday for at least a month so for a period Hašek surely produced more or less the entire content. This was also the time when his above-mentioned erroneous translation[n] of Eichelhäher (jay) allegedly caused a stir amongst ornithologists[k]. Sharks by Messina, mistakenly assumed to be one of Hašek's inventions. ,15.7.1909

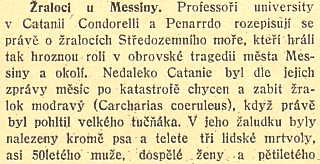

In the same issue appeared a sensational story called Sharks by Messina where inside a shark were found the bodies of three humans, a dog and a calf, and the bodies were well preserved and even dressed[m]. At first sight, the story bears the hallmarks of a grotesque invention and scholars have indeed assumed that it was. This is however not the case as several European and even American newspapers reported on the incident in early July 1909.

The reports are related to the earthquake disaster that hit Sicily and Calabria on 28 December 1908. The shark was caught by fishermen on 26 January 1909 and its stomach content was analysed by two professors from Catania University. They concluded that the victims probably were washed into the sea by the resulting tsunami and subsequently devoured by the animal[l]. The grisly story was recently mentioned in National Geographic[p]. The news as presented in Svět zvířat however makes it appear more grotesque than it actually was, giving the impression that inside the shark were found fully dressed bodies and not merely body remnants and rags.

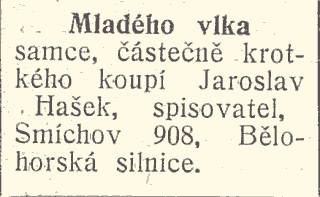

Hašek wanting to buy a young wolf! ,15.3.1910

That Svět zvířat printed the story is probably more a testimony to Hašek's tendency towards the bizarre and sensational rather than being an example of a hoax. Similarly, many of his stories that are believed to be mystification may not be - rather resulting from Hašek's preferences when selecting material for publishing.

Hašek may have translated numerous such stories and twisted them slightly but verifying them is still a work in progress. The scholars who prepared the excellent "Entertaining and Education Corner of Jaroslav Hašek"[q] for obvious reasons didn't have the capacity nor the means to carry out such detailed investigations across all the foreign journals that may have carried the original news.

Hašek also "contributed" to Svět zvířat in an unexpected way. On 3-4 occations he advertised in the journal, wanting to buy animals. In one case he advertised, wanting to buy a young wolf. This suggests that he was already trading in animals, a prelude to his Kynological Institute? But by all accounts he wasn't interested in werewolves, other than as vehicles for his mystifications!

Josef Lada the poet. ,15.7.1910

Amusing extras are the items that Hašek attributed to his friends. Both Opočenský and Josef Lada provided "signed poems" and Lada was even presented as a "translator of Hungarian" (Opočenský's poems may have been real). The story of Engineer Khún's Flea is in the same category. Here Hašek simply translated a story from German and swapped the name Klebs with that of his friend Kún!

Although the reading public automatically thinks of hoaxes when the words Svět zvířat and Hašek are mentioned together, it should not be forgotten that Hašek generally wrote entirely solid articles or humorous stories. These often revealed his impressive general knowledge, at times interspersed with non-zoological themes that we know from The Good Soldier Švejk (e.g. Xenophon, Lombroso). His affection for animals also shines through!

Photomontages and April Fools

Chief editor Ladislav Hájek wrestling with a tiger.

,1.4.1913

Professor Jindřich Toman points to a lesser-known feature of Svět zvířat: the photomontages[x]. Unsurprisingly these often appeared on the first of April. On 1 April 1911, the journal printed a photo that showed animals from the Hagenbeck Circus parading at Na Příkopě and one year later a picture of a giant rabbit on the South Pole appeared. Both these jokes were however published during a period when Hašek didn't work for Svět zvířat. In both cases the photo montages was so large that the chief editor (Václav Fuchs and Ladislav Hájek respectively) would have known about them.

On 1 April 1913, Svět zvířat printed a photo that shows Ladislav Hájek wrestling with a tiger and this one was surely the work of Hašek. The photo was accompanied by an amusing text, and in the same issue some incredible information about the rhinosaurus and a deformed carp was published. In the next issue Svět zvířat refuted it's own April Fool's jokes and made fun of those who had not noticed that it was 1 April! It was also announced that Právo lidu had snatched at the bait and that some people had even ordered tigers!

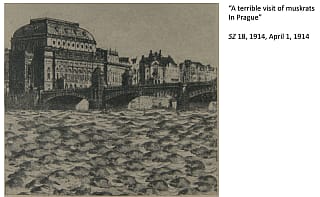

One year later a photo of the Vltava being flooded with muskrats appeared but by now Hašek had again left the magazine. Václav Menger picked up the news about this picture and dubiously claimed it was a joke by Hašek. Menger probably wasn't aware of the Hašek - Svět zvířat timeline and evidently didn't read the magazine, claiming the photo was of the Vltava by Vyšehrad (the scene is the Vltava by Národní divadlo). Cecil Parrott later translated part of Menger's tale (more on Parrott later).

In general, the use of photomontages was widespread in Svět zvířat and they actually seem less frequent (at least less obvious) during Hašek's two periods at the journal. Still, even today, some literary scholars interpret these April Fool's Day jokes as hoaxes by Hašek, neither taking his spells as editor nor the date 1 April into account[w].

Compilations

There exist many collections of Hašek's short stories, published in book form after the author's death. The first of these was The Collected Writings of Jaroslav Hašek (1926), a series of softback instalments that were not thematically arranged. Thus items from Svět zvířat appear in several of those but without bibliographical references.

Malá zoologická zahrada

,1950

The first scholar to seriously investigate Hašek and his endeavours in Svět zvířat was Břetislav Hůla. In 1950 the book Malá zoologická zahrada (The Small Zoological Garden)[r] was published with Zdena Ančík listed as editor although Hůla no doubt did the groundwork. Most of this book is made up of Hašek's stories from various publications but it also contains 17 brief articles that the editor(s) assumed that Hašek wrote. Amongst those 17 items very few were actually written by Hašek...

Zábavný a poučný koutek Jaroslav Haška

Only as late as in 1973, after two decades of research, did a more convincing study of Hašek and his activities at Svět zvířat appear. The book is part of the series Spisy Jaroslava Haška (The Writings of Jaroslav Hašek) and is called The Entertaining and Educational Corner of Jaroslav Hašek[q]. It provides unique insight and importantly: this compilation contains literature references. It also has some material from České slovo and Svět, but most of the entries are from Svět zvířat.

Particularly illuminating is the epilogue by Radko Pytlík. Here the distinguished Hašek-expert, without stating it directly, exposes most of the myths surrounding Hašek and his career at the zoological journal. Importantly, Pytlík also emphasises that Hašek often reused motifs from Svět zvířat and other periodicals when he wrote The Good Soldier Švejk.

O Haškových pověstných mystifikacích jsme doposud věděli jen z

jeho pozdějšího humorného vyprávění, zejména z příslušných kapitol Dějin

strany mírného pokroku, z črty V přírodovědeckém časopise a z vyprávění

jednoročního dobrovolníka Marka ve Švejkovi. Podle shod, jež se nám nyní

po podrobném průzkumu časopisu podařilo objevit, zjišťujeme, že jsou v

pozdějším vyprávění vesměs přehnány a přetvořeny.

Radko Pytlík, 1973

The Animal World reflected in Švejk

Many themes from the animal journal found their way into The Good Soldier Švejk

,1.7.1910

Although six of the seven species that Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek "invented" have no direct parallels in the columns of Svět zvířat, his story on the troop transport train from Budějovice to Bruck includes many themes that are related to Hašek's experiences as editor of the journal. Marek's version of how he succeeded Hájek is partly authentic and he mentions both the journal's owner Fuchs and his daughter (who Hájek indeed was in love with and later married). Engineer Khún's Flea and the follow-up in the columns of Čech and Čas is also a point where The Good Soldier Švejk and Svět zvířat overlap, although not in the way that Marek describes. Already mentioned is Marek's misnaming of the jay (sojka).

Motifs from other parts of The Good Soldier Švejk can also can traced back to Svět zvířat. One example is the story about Rittmeister Rotter and his police dogs, a tale that appears twice in the novel. Rotter contributed to the journal and at least twice it printed photos of him. He also bought dogs from Psinec nad Klamovkou. Another person that Hašek would have known from his time above Klamovka was beekeeper Pazourek who wrote in virtually every issue and also appears on several photos. The reader will also recognise numerous dog breeds, one example being the Leonberger. Further animals appear both in the journal and in The Good Soldier Švejk: Harz (canary), Engadin and Saanen (goats), Yorkshire (pig), Wyandotte (chicken), Angora (cat) etc. Another intersecting point is some dog exhibition in Berlin (see Berliner Stallpinscherausstellung ).

Mr. Jaroš from Králupy is another common theme. This pump manufacturer advertised in Svět zvířat and is also mentioned in a minor notice.

Marek's Seven Wonders of The Animal World

Seven animal species were "discovered" by Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek during the time he edited Svět zvířat, summarised in the table below. The English names and Marek's words are from Zenny Sadlon's translation (2009). The names used by Cecil Parrott (1973) differ slightly and Paul Selver (1930) left Marek's experiences at the journal out of this translation altogether.

| Czech | English | Marek | In Svět zvířat |

|---|---|---|---|

| velryba sírobřichá | sulphur-bellied whale | this new whale species of mine had the size of a cod fish and was equipped with a bladder filled with formic acid... | On 1 June 1909 the editorial Modern whale-hunting was published, signed Frant. Winter. Here the sulphur-bellied whale is mentioned and but is revealed as another word for the blue whale. The article is translated from German, most probably by Hašek. |

| blahník prohnaný | blisser-the-artful | a mammal from the kangaroo family | No obvious connection. |

| vůl jedlý | ox-the-edible | archetype of the cow | No obvious connection. |

| nálevník sepiový | sepian infusorian | which I characterized as a type of sewer rat | Infusoria are microorganisms living in freshwater. They are mentioned in Svět zvířat (e.g. 1 March 1912) but not at the time when Hašek edited the magazine. The word sepiový also appears but not in a context that can be linked to the description in The Good Soldier Švejk. |

| netopýr vzdálený | bat-the-remote | a bat from the island of Iceland | Bats are mentioned many times during the time Hašek edited Svět zvířat. Interesting is a minor item about bats, dated 1 February 1909. This was printed at the very beginning of Hašek's editorship. On the other hand: Iceland is not mentioned at all. |

| pačucha jelení dráždivá | deer-sniffer the irritable | domestic cat from the summit of the mount Kilimanjaro | No obvious connection. |

| blecha inženýra Khúna | engineer Khún’s flea | found in amber and blind “because it lived on an underground prehistoric mole, which was also blind | A story with many similarities was published on 1 September 1911, albeit at a time when Hašek no longer worked for Svět zvířat. The story was exposed as a hoax by Právo lidu on 19 August 1913, causing minor headlines in several newspapers. See Engineer Khún's Flea. |

Myths

The sulphur-bellied whale was real enough (big blue) but in a literary context Hašek changed its attributes drastically!

,1.6.1909

The entire story of Jaroslav Hašek's life is shrouded in legend and his period as editor of Svět zvířat is a prime example. Many of the more or less credible stories related to Hašek and The Animal World circulate even to this day (2024) and some have found their way into foreign-language books, academic papers, and websites (including the one you are currently looking at).

Most widespread is the claim that Hašek published stories about imaginary species, rumours that he himself may have set in motion already before his dismissal from the journal in late 1910[a].

Less than a year later he extended his claim to be "an inventor of animal" to a wider audience by writing a story called In the Natural Science Journal[e]. Here the narrator invents the sulphur-bellied whale, the frightening gobbler, advertises werewolves for sale, and reveals the existence of other hitherto unknown species. He also claimed that he had written that ants like "La Traviata" and that hippos enjoy it when "natives blow up their noses" (the latter he actually wrote). The first-mentioned revelation overlaps slightly with Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek's "discoveries" in The Good Soldier Švejk but otherwise, the creations differ. The whale is an example of how Hašek used factual information as a seed for his mystification.

Obviously, Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek's adventures as told in The Good Soldier Švejk further underpinned the myths about fictional animals and other improbable stories. But by the time this part of The Good Soldier Švejk was written (1921), Hašek was no longer alone in the trade. Already in 1918 Josef Mach published news about some of Hašek's inventions at Svět zvířat, for instance, another variation of Hašek's own werewolf story[f].

Obituary

The obituary in Prager Tagblatt also mentioned the werewolf and even claimed that Hašek had advertised wereswolves and mermaids for sale in Svět zvířat. Pointingly, the author of the obituary noted that Hašek was capable of lying in such a convincing manner that everyone believed him[zz]. Unwittingly the jounalist in Prager Tagblatt confirmed this very point by mentioning the werewolves and the mermaids! The obituary is signed "k" and there is every reason to assume that it was written by Egon Erwin Kisch (Hans-Peter Laqueur)!

Er log, wie einer seiner Freunde bemerkt hat, mit der Nonchalance eines Gentleman, so schamlos unschuldig, daß ihm jeder glaubte. Er hat das Unwahrscheinlichste mit einem professorenmäßigen Gründigkeit, mit analytischem Kritizismus, mit vielen Zitaten und Belegen, so detailmäßig erzählt, daß der Unglaube der Hörer selbst schädigen mußte. Als er als Redakteur der Tierzeitung Svět zvířat die phantastischen Berichte neben seine Zucht von Werwolfen, Meerjungfrauen (deren Verkauf er auch inseriert hat) veröffentlichte, bekam er hunderte Zuschriften guter Menschen.

Prager Tagblatt, 5. Jänner 1923

Biographers adding spice

The polemic between Čas and Čech that Marek talked about actually took place but only after Hašek had left Svět zvířat. The prehistoric flea was authentic enough and the only sin Hašek committed was to change the name of it from Klebs' flea to Khún's flea! Curiously the news about the flea was printed on 1 September 1911, at a time when Hašek no longer worked for the journal.

,21.8.1913

After Hašek's death, many of his friends published their reminiscences, including colourful accounts of the ongoings at Svět zvířat.

Franta Sauer was the first of these and provides an interesting note about Engineer Khún's Flea. He claimed that Hašek himself wrote the notice in Právo lidu that eventually sparked the polemic between Čech and Čas (mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk). This is entirely plausible and would be typical of Hašek! Sauer also claimed that the direct cause for Hašek's dismissal was that he had given readers bogus advice against some poultry disease and as a result, many birds died[g]. The magazine was allegedly flooded with complaints and even claims for compensation. Sauer's version remains unconfirmed and seems to be a mix of fact and fiction.

Concerning Svět zvířat, the by far most reliable information was put in print by Ladislav Hájek in 1925. As already mentioned was the editor of the journal both before and after Hašek's intermezzo and as directly involved few knew better the circumstances around Hašek's engagement at the journal and also his demise. Hájek's account is generally factual although chronologically vague. One surprise is his claim that Hašek "invented a fly with sixteen wings"[a], an creature that so far has not been identified in the columns of Svět zvířat.

In 1928 Emil Artur Longen added considerable spice to the legends. The werewolf again raised its bristles, Hašek had allegedly found a prehistoric flea in a piece of amber and had invented animals with the adroitness of the Creator himself[h]. Every issue of Svět zvířat is said to have contained some surprise and angry readers returned the magazine...

In 1935 Václav Menger followed up with more news. Hašek had allegedly written an item called Rational Breeding of Werewolves and also offered his creations for sale. Menger informed that Hašek had published an April Fools' Day joke photomontage that showed the Vltava below Vyšehrad being flooded with muskrats (ondatra) and that people had flocked to the river to watch the rare animals. Hašek had also allegedly transformed the serious magazine Svět zvířat into an entertainment periodical, and that within a few issues...[i]. Muskrats (ondatra) in the Vltava. This April Fools' photo montage with an accompanying text is mentioned in at least two biographies on Hašek (Menger, Parrott), albeit in somewhat twisted guises. It was however printed on 1 April 1914 and it is thus unlikely that Hašek had anything to do with it. Parrott didn't even notice that it was a joke.

Although being largely at odds with reality, Václav Menger's version is important in the sense that it was passed on to foreign readers through the Hašek-biographies of Gustav Janouch (1966), Cecil Parrott (1978), and Jan Berwid-Buquoy (1989).

After World War II Gustav R. Opočenský, Josef Lada, and František Langer published their reminiscences but only Lada seems to provided details about Hašek's time above Klamovka. Lada informs that Hašek made him into a translator of Hungarian and published poems using his name! This is indeed true[u][v] but his claim that Hašek also made him into a translator of Permyak has not been verified.

In addition, Lada blew the story of Engineer Khún's Flea out of all proportion by claiming that it was a detailed article written by Hašek himself. The flea story was allegedly translated into foreign languages and caused a heated debate amongst scientists abroad!

When stating that biographers added spice space it would be wise to ponder where the amusing but nonsensical information actually hailed from. The likely source is of course Jaroslav Hašek himself. Still, this doesn't rule out that some of his friends added a tune or two! That Mach, Sauer, Longen, Menger and Lada actually studied Svět zvířat in detail seems very unlikely. The Bad Bohemian, ,1978

Significantly, much of the incorrect information from Menger and Lada hit the international stage years later via The Bad Bohemian (1978) by Cecil Parrott, so far the only English-language biography written about Jaroslav Hašek. In this generally solid book, Parrott unreservedly passed on the stories about the werewolves and the muskrats, and in the latter case, he even left out Václav Menger's note that it was an April Fool's joke. In addition, some of Josef Lada's equally improbable claims (e.g. about Engineer Khún's Flea), reached the anglophone readership through this book. Parrott in this book however never claimed that Hašek invented animals, but in the introduction to his translation of The Good Soldier Švejk (1973), he had done so.

Radko Pytlík was more prudent and stated that "at first sight, it is not obvious what is a prank and what is a mere curiosity" (Toulavé house, 1971). Despite this sombre precaution the distinguished scholar concluded, without providing further evidence, that Hašek invented animals...

Abenteuer auf Deutsch

The two German-language biographies about Jaroslav Hašek that exist as of 2024 both present an even more distorted picture. Both include dialogues between Fuchs and Hašek as if the authors were flies on the wall above Klamovka in 1908 and listened in on the conversation... ,1966

The first ever foreign-language Hašek-biography was published by Gustav Janouch in 1966. The book is well-written, and contains a wealth of information, a comprehensive literature list and also references[y]. Still, the section about Hašek and Svět zvířat is of dubious veracity (pages 88-94). The quoted conversation between Fuchs and Hašek (with Hájek present) raises many questions: Did Janouch simply invent the dialogue, or did he have some source? He could at a push have spoken to Hašek at some stage but not to Fuchs. He quotes Hájek but his book doesn't reproduce such a conversation at all[a]. Already the first issue of Svět zvířat that Hašek edited is claimed to have caused circulation to skyrocket (borrowed from Václav Menger?). Even the famous picture of Emperor Franz Joseph I. on the bridge is claimed to have been published by Hašek in Svět zvířat in 1909. This is of course pure nonsense, the picture was printed in several magazines in 1901 and is not to be seen in Svět zvířat (see starý Procházka)! Janouch was still thorough enough to quote his source: some former police director, now living in Karlovy Vary, Jan Chudoba! The result is thereafter...

,1989

Hašek had allegedly also transformed Svět zvířat into a humour magazine, again the echo of Václav Menger lingers... In short, Janouch twisted Ladislav Hájek's account drastically to make it more "interesting". Needless to say, Hašek's own mystifications about his time at Svět zvířat also creep in, for instance, the werewolves. Janouch was well connected amongst Hašek friends, he knew Sauer and Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj and the journalist Michal Mareš but none of them was in much contact with Hašek during his time at Svět zvířat so whatever they told him could at best be second-hand information and probably mere hearsay.

The second biography written in German was penned by Jan Berwid-Buquoy in 1989 and also deals with the theme Svět zvířat and Hašek (pages 150-158)[z]. It is arguably the most entertaining book about Hašek ever written but correspondingly speculative and unreliable fact-wise. First of all, it reproduces Janouch's "conversation" between Fuchs and Hašek, but with added spice (two beers become five). Then Hašek is even declared the inventor of the term "Werwolf - vlkodlak"! The author also mixes up the roles of Hájek and Hašek concerning Fuchsová and adds some of the better-known legends that Hašek himself created, like the terrible guzzler.

As previously mentioned, the legends as expressed in German existed already at least from from 5 January 1923. That day some writer K. (Egon Erwin Kisch ?) published Hašek's obituary in Prager Tagblatt an released into the German speaking world Hašek's werewolves and even mermaids that he allegedly advertised in Svět zvířat![zz]

Disintegrating legends

Hašek is the most likely source of most of the legends about his time as editor of Svět zvířat. Here he claims to have advertised young werewolves for sale in the journal.

,6.6.1912

With Svět zvířat becoming available and searchable online in May 2024 the vast majority of the myths surrounding Hašek and his contributions to the journal starts to fall apart.

Already before this, Dr. Martin Dvořák had studied and presented Svět zvířat at conferences in Lipnice and Kraków (June and November 2023). The owner of this website owes Dvořák a great deal for benevolently sharing his personal scans of the magazine (November 2023).

As Dvořák noted already in 2023: in the Svět zvířat there are no signs of werewolves or any of the other creatures that Hašek claims to have invented, be it as Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek in The Good Soldier Švejk, in his short stories, or in the words of his friends and biographers. The sulphur-bellied whale is mentioned but in a matter-of-fact context (it is another name for blue whale) and the same goes for the muskrats, jays etc. Marek's and Hašek's zoological creations are conspicuously absent.

Why was Jaroslav Hašek dismissed?

A pair of young acorners. Creating a new term for the jay in 1909 could not have been the reason for Hašek's dismissal more than a year later.

,15.7.1909

As usual, when Jaroslav Hašek is the theme conflicting testimonies abound. Based solely on reading The Good Soldier Švejk one might conclude that Hašek, as the real-life counterpart to Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek, was thrown out of Svět zvířat because of the affair with Engineer Khún's Flea combined with the invention of the new term acorner (instead of jay). Creating new species and providing alarming stories about bee- and poultry diseases also contributed to Marek's fall from grace.

Sauer claims that the final straw for Fuchs was some advice given in the journal about remedies against poultry disease, but this seems improbable and sounds like an echo from The Good Soldier Švejk.

The episodes regarding the pre-historic flea and the jay indeed took place but they could not possibly have contributed to Hašek leaving the magazine in October 1910. The flea controversy surfaced in 1913 and the affair with the jay happened already in 1909.

Václav Menger claims that the final straw for the journal's owner was an article Hašek had written where he wrote that muzzles on dogs causes rabies! Allegedly a reaction was printed in Národní politika. An article about muzzles and rabies indeed appeared in Svět zvířat on 1 August 1909 but it was signed Václav Fuchs himself! Hašek was capable of the most incredible mischief but surely he wouldn't have the audacity to publish such a story in his employer's name... Even if he did write the article the timing rules out that it provoked his dismissal more than a year later.

Ladislav Hájek offers a more mundane explanation: Hašek's irregular presence in the office and complaints from readers about dubious information were understandably more than the magazine owner Fuchs could tolerate[a]. In other words: Hašek was fired because he didn't do his job properly. This is also the most likely explanation.

Support for this hypothesis is found in the afterword to The Entertaining and Educational Corner of Jaroslav Hašek. Here Radko Pytlík concludes that researchers could not find any proof as to why and when Hašek left the journal. Nor did they on its pages identify any specific mystification that could have been a cause for termination[q].

Nepodařilo se však najít důkaz, proč a kdy Hašek z tohoto listu odešel. Hájek líčí, že majitel Světa zvířat byl prý nespokojen s jeho lehkovážným vedením listu; ale konkrétní mystifikaci, která by mohla být záminkou k výpovědi, jsme v listě nenalezli.

Radko Pytlík, 1973

Conclusion

Studying Svět zvířat and verifying the content against what has been written about it and Hašek over the years is still (2024) work in progress. It is thus apt to emphasize that although we have seen no evidence that Jaroslav Hašek invented new animal species, it still can't be entirely ruled out. Nor is the OCR technology that creates searchable digitized journals perfect yet.

In the end, the only pranks that have been identified narrow down to an unknown number of little jokes like making Josef Lada a poet and a translator of Hungarian and letting the natives blow up the baby hippo's nostrils. In the same category is Engineer Khún's Flea. In addition, in the journal can be found numerous items that appear to be pranks but may just as well be selected curiosities. Thus there is scope for further investigations.

That said, it is safe to conclude that Hašek largely mystified his famous animal mystifications, be it in The Good Soldier Švejk, his short stories or his revelations in Strana mírného pokroku v mezích zákona. Cecil Parrott sensibly concluded that Hašek was an "accomplished and persuasive hoaxer". Little did the respected Hašek expert know that he, like numerous others, indirectly fell into the trap by passing on the myths produced by Václav Menger and Josef Lada, "information" that surely Hašek himself set in circulation!