Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie leave the Sarajevo Town Hall on 28 June 1914, five minutes before the assassination.

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel with an unusually rich array of characters. In addition to the many who directly form part of the plot, a large number of fictional and real people (and animals) are mentioned; either through the narrative, Švejk's anecdotes, or indirectly through words and expressions.

This web page contains short write-ups on the people/animals that the novel refers to; from Napoléon in the introduction to Hauptmann Ságner in the last few lines of the unfinished Part Four. The list is sorted in the order of which the names first appear. The chapter headlines are from Zenny Sadlon's recent translation (1999-2008) and will in most cases differ from Cecil Parrott's version from 1973.

The quotes in Czech are copied from the on-line version of The Good Soldier Švejk: provided by Jaroslav Šerák and contain links to the relevant chapter. The toolbar has links for direct access to Wikipedia, Google maps, Google search, svejkmuseum.cz and the novel on-line.

The names are coloured according to their role in the novel, illustrated by the following examples:

- Dr. Grünstein as a fictional character who is directly involved in the plot.

- Fähnrich Dauerling as a fictional character who is not part of the plot.

- Heinrich Heine as a historical person.

Note that a number of seemingly fictional characters are inspired by living persons. Examples are Oberleutnant Lukáš, Major Wenzl and many others.

Military ranks and some other titles related to Austrian officialdom are given in German, and in line with the terms used at the time (explanations in English are given in tooltips). This means that Captain Ságner is still referred to as Hauptmann although the term is now obsolete, having been replaced by Kapitän. Civilian titles denoting profession etc. are translated into English. This also goes for ranks in the nobility, at least where a direct translation exists.

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all

People index of people, mythical figures, animals ... (587)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30)

1. The good soldier Švejk acts to intervene in the world war (30) 14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (35) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (22) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (55) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (46) 5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44)

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal (44) III. The famous thrashing

III. The famous thrashing  1. Across Magyaria (52)

1. Across Magyaria (52) 2. In Budapest (32)

2. In Budapest (32) 3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31)

3. From Hatvan to the borders of Galicia (31) 4. Forward March! (32)

4. Forward March! (32) IV. The famous thrashing continued

IV. The famous thrashing continued  1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35)

1. Švejk in the transport of russian prisoners of war (35) 3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

3. Švejk again with his march company (20)

|

II. At the front |

| |

4. New afflictions | |||

| Saint Stephen I |  | |||

| *967-978 Esztergom - †15.8.1038 Esztergom? Székesfehérvár? | |||||

| |||||

Saint Stephen I is mentioned in the article in Pester Lloyd that Oberleutnant Lukáš reads out for Oberst Schröder. The reference is done indirectly through the expression The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen, i.e. the kingdom of Hungary.

Background

Saint Stephen I is the patron saint of Hungary and regarded as founder of the country. Until the break-up of Austria-Hungary, the Hungarian part of the empire was officially called The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Současně však očekáváme úřední zprávu o királyhidském zločinu, spáchaném na maďarském obyvatelstvu. Že se věcí bude zabývat pešťská sněmovna, je na bíle dni, aby nakonec se ukázalo jasně, že čeští vojáci, projíždějící Uherským královstvím na front, nesmějí považovat zemi koruny svatého Štěpána, jako by ji měli v pachtu.

Also written:Štěpán I. SvatýczI Szent Istvánhu

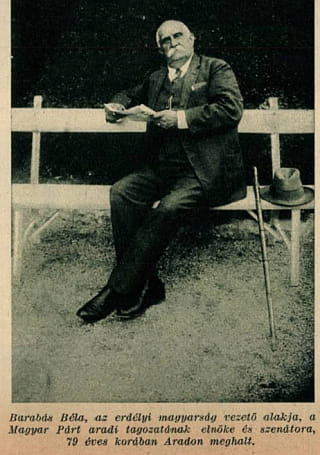

| Deputy Barabás, Béla |  | ||||

| *12.12.1855 Arad - †28.5.1934 Arad | ||||||

| ||||||

,30.5.1934

,6.5.1915

,6.5.1915

,6.5.1915

Barabás was the editor and member parliament who signed an article that had appeared in Pesti Hírlap and the in Pester Lloyd. It was title "Where is the guarantee of our future?"". Barabás was according to Oberst Schröder known as a beast.

Background

Barabás was a lawyer, author and politician, member of the lower chamber of the Hungarian Parliament from 1892 to 1910 and again from 1911 to 1917. His role as a newspaper editor was however limited to publications in his home area around Arad (now Oradea). He remained politically active in Romania after the war.

Anti-Habsburg

Barabás represented the Independence Party (Függetlenségi Párt), a party opposed to Ausgleich, advocating a personal union instead. Given his party allegiance one would expect an anti-Habsburg stance and this manifested itself in a spectacular way in 1902 during the first session of parliament in their grand new building[a].

Arrested in France

After the outbreak of war he appeared on the front pages of several newspapers because he and some other Hungarian deputies were arrested in France. Due to his relatively high age he was released and travelled back home via Brest, Amsterdam and Cologne.

In the Pest newspapers

There is no evidence that he wrote chauvinistic articles in Pester Lloyd or Pesti Hírlap on the line of the one quoted in The Good Soldier Švejk. That said, both newspapers would surely have reported on his anti-Austrian outbursts in the Hungarian Parliament.

Hašek inspired by a budget debate?

One possible influence is a budget debate in the parliament on 5 May 1915 where Barabás hailed the sacrifice and effort of the Hungarian nation, that the centrepoint of the monarchy now was in Hungary. He openly accused Austria of not doing it's duty with regards to military efforts, that a lot of Austrian personnel fit for military service had not yet been called up. He also quoted rumours about the trustworthiness of "certain Austrian nations" (read Czechs). Furthermore, he emphasized the patriotism and will to sacrifice amongst the Hungarian troops, and also the patriotism of the Hungarian parliament[b].

Then he asked for the same attitude amongst the Austrian troops. The debate was covered by most newspapers and it is very likely that Jaroslav Hašek who at the time had reported sick in Budějovice knew about the controversy and that he had noted the attitudes of Barabás.

As a response Honvéd minister Hazai answered the accusations from Barabás and stated that he, from first-hand knowledge, could confirm that patriotism was every bit as strong in Austria as in Hungary.

Not part of the previous version of Švejk

Although the brawl in Királyhida also features in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, there is no mention of Barabás in this second version of The Good Soldier Švejk. Despite the two stories being roughly similar, many details, also apart from Barabás differ. This mainly applies to names and roles.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] „Kdo je podepsán pod článkem, pane nadporučíku?“ „Béla Barabás, redaktor a poslanec, pane plukovníku.“ „To je známá bestie, pane nadporučíku; ale dřív, nežli se to dostalo do ,Pester Lloydu’, byl již tento článek uveřejněn v ,Pesti Hírlap’.

Literature

- Osud zajatých poslanců z Uher4.9.1914

- Bela Barabás propuštěn15.9.1914

- Z uherského parlamentu6.5.1915

- Budgetdebatte in Ungarn6.5.1915

- Unabhängigkeitspartei1909

| a | Die erste sitzung im neue Parlamente | 8.10.1902 | |

| b | Die Frühjahrstagung des Parlaments | 6.5.1915 |

| Deputy Savanyú, Géza |  | ||||

| ||||||

,3.9.1912

,1913

,1910–1915

Savanyú represented Királyhida district in the Hungarian Parliament. According to Sopronyi Napló he was going to raise the issue of Oberleutnant Lukáš' letter scandal and the ensuing brawl.

Background

Savanyú was according to the text of The Good Soldier Švejk member of parliament, representing the Királyhida district. This MP is surely dreamt up as Királyhida was no district, be it political, juridical or electoral. Nor was there any deputy Savanyú in the entire Hungarian Diet.

Districts

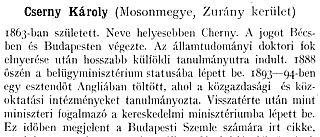

The judicial district was Nezsider (Neusiedl am See) and the political district Moson. The electoral constituency that Királyhida belonged to was Zurány (now Zurndorf)[a] and the deputy from 1910 to 1918 was Károly Cserny (1863-1933), an experienced diplomat and politician.

Reuse of names

Circumstances indicate somewhat random reuse of names. Savanyú is a surname that also appears later in The Good Soldier Švejk and the author had already before the war used it in two stories. See Róža Šavaňů.

Tamás Herczeg

The deputy of Királyhida from 1910-1915 was: Cserny Károly. (Károly Cserny in English form.)

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Toto se týká zejména jednoho pána, který se dle doslechu zdržuje doposud beztrestně ve vojenském táboře a stále ještě nosí odznaky svého ,papageiregimentu’ a jehož jméno bylo též uveřejněno předevčírem v ,Pester Lloydu’ a ,Pesti Napló’. Jest to známý český šovinista Lükáš, o jehož řádění bude podána interpelace naším poslancem Gézou Savanyú, který zastupuje okres királyhidský.“

Sources: Klara Köttner-Benigni, Tamás Herczeg

Literature

- Cserny Károly

- Cserny Károly

- Die deutsch-ungarischen Beziehungen18.8.1915

- Řádný učitelJaroslav Hašek3.11.1907

- Velká Kaniža a KörmentJaroslav Hašek26.4.1913

| a | Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich | 1983 |

| Painter Panuška, Jaroslav |  | ||||

| *3.3.1872 Hořovice - †1.8.1958 Kochánov | ||||||

| ||||||

,3.3.1932

Hašek na smrtelném loži, Jaroslav Panuška

© Galerie moderního umění v Hradci Králové

Panuška briefly enters The Good Soldier Švejk when Švejk during interrogation at Hauptwache defends himself by quoting his servant Matěj.

Background

Panuška was a Czech painter and a friend of Jaroslav Hašek. It was he who persuaded Hašek to go with him to Lipnice on 25 August 1921 [a] and there Hašek remained until he died, less than 17 months later.

Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj, Emil Artur Longen and Josef Lada also belonged to their common circle of friends. Well known is a non-flattering portrait that Panuška made of Hašek towards the end of the author's life and also a drawing of the dead Hašek in his bed.

When Panuška and Hašek became friends is not clear but it may have been through Kuděj who met Panuška around 1920. Whether or not Panuška employed a servant and if he was actually named Matěj can not be established.

Lifeline

As a trained "academic painter" Panuška had already in 1897 seen one of his painting reproduced in the press. It was published in Volné směry, a sinister picture of a headless horse[b]. He was known for his landscape paintings, often with a gloomy undercurrent. Several of his paintings were from Lipnice and the surrounding area, and he lived in nearby Kochánov from 1923 onwards. Panuška was married and fathered four children.

Cecil Parrott, The Bad Bohemian, 1982

In the summer of 1921 Hašek suddenly disappeared from Prague. The person responsible for whisking him away was the landscape painter, Jaroslav Panuška, a great hulking man of enormous strength, who would have been a good 'chucker out' at a pub and had indeed proved himself as such. Among his eccentricities was to address everybody in the familiar second person singular, to save himself the trouble of distinguishing between his closest friends and the rest. He had an atelier in Vinohrady and was at one time friendly with Lada, the illustrator of Švejk. A great drinker and gourmand, he combined just those qualities which were dear to Hašek's heart. More important, he was a kindly person who took a real interest in Hašek's welfare.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Tak na př. na otázku, proč se nepřizná, odpověděl dle protokolu: ,Já jsem zrovna v takový situaci, jako se voctnul jednou kvůli nějakejm obrazům panny Marie sluha akademického malíře Panušky. Ten taky, když se jednalo o nějaký vobrazy, který měl zpronevěřit, nemoh na to nic jinýho vodpovědět než: »Mám blít krev?«

Sources: Cecil Parrott, Radko Pytlík

Literature

- Malíř Jaroslav Panuška

- Franta Habán ze Žižkova1923

- Jaroslav Hašek1928

- Jaroslav Panuška15.7.1898

- Několik vzpomínek na Jaroslava Haška27.12.1928

- Jaroslav Panuška - 60 Jahre3.3.1932

- Z mého života1945

| a | Toulavé house | 1971 | |

| b | J. Panuška - Pohádky | 2.1897 |

| Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk |  | |||

| |||||

,13.4.1924

Vaněk is mentioned 148 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Vaněk is the accounting sergeant at the staff of 11. Kompanie in Királyhida, in civilian life a chemist from Kralupy. He is depicted as a rather cynical reserve officer, looking after himself first and foremost. Moreover, he enjoys a tipple or two. His wife runs the shop when he away and later in the novel he sends here instructions.

Vaněk is first mentioned in [II.4] when Oberst Schröder gives him the task to find a new servant for Oberleutnant Lukáš after Švejk's promotion to company messenger. Vaněk's first words in the novel are uttered after receiving the news about the change of roles: "May God help us all!". In the next chapter he meets Švejk for the first time and in the rest The Good Soldier Švejk he features regularly.

In various conversations (he likes to relate from his experiences in the field) it is revealed that he has served with three march companies already, in Serbia and in the Carpathians. With 10. Marschkompanie he had served by Dukla.

Background

The real-life inspiration for Vaněk is without Jan Vaněk. Like his literary counterpart he was a "drogista" from Kralupy and served as a staff sergeant in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91, and in the same company as Jaroslav Hašek. Amongst the "models" for characters in The Good Soldier Švejk Vaněk is probably the person that shows the most similarities with his literary counterpart. The only striking difference is that Hašek assigned the literary Vaněk a trait that the "model" didn't have: addiction to alcohol.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Nadporučík Lukáš po celé cestě domů si opakoval: „Kompaniekomandant, kompanieordonanz.“ A jasně před ním vyvstávala postava Švejka. Účetní šikovatel Vaněk, když mu poručil nadporučík Lukáš, aby mu vyhledal nějakého nového sluhu místo Švejka, řekl: „Já myslel, že jsou, pane obrlajtnant, spokojenej s tím Švejkem.“ Uslyšev, že Švejka naznačil plukovník ordonancí u 11. kumpanie, zvolal: „Pomoz nám pán bůh!“

[II.5] Před ním stál účetní šikovatel Vaněk, který zde sestavoval listiny k výplatě žoldu, vedl účty kuchyně pro mužstvo, byl finančním ministrem celé roty a trávil tu celý boží den, zde též spal.

[II.5] Účetní šikovatel Vaněk byl tak překvapen tím familiérním sousedským tónem dobrého vojáka Švejka, že nedbaje své důstojnosti, kterou velice rád ukazoval před vojáky kumpanie, odpověděl, jako by byl Švejkův podřízený: "Já jsem takto drogista Vaněk z Kralup."

Sources: Jan Morávek, Bohumil Vlček

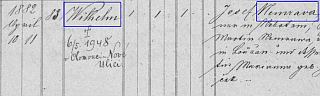

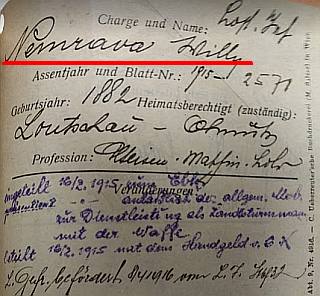

| Nemrava, Wilhelm |  | ||||

| *Hněvotín 10.4.1882 - †Olomouc 6.5.1948 | ||||||

| ||||||

Birth and baptism record, Hněvotín, 1882

, 25.11.1905

,22.6.1907

,23.6.1907

,20.11.1907

Venkov,3.6.1915

,16.10.1930

Lidové noviny,4.6.1931

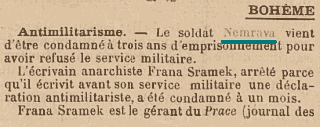

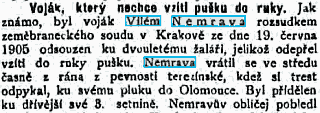

Nemrava was according to Švejk someone who before the war lived in Moravia and who had refused to carry arms and was repeatedly imprisoned because of this. At least this is what he tells Sappeur Vodička when the two are locked together at Hauptwache in Brucker Lager after the scandal with Mr. Kakonyi.

Background

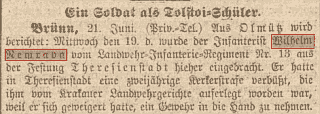

Nemrava and the conversation in Királyhida has a factual background and what Švejk says is indeed authentic. On 1 November 1904 the recruit Vilém Nemrava from k.k. Landwehrinfanterieregiment Nr. 13 in Olomouc refused to swear oath to the flag[a] and was sentenced to a 5 month prison term.

Back with his regiment after his release he again refused to obey orders. According to his conviction he refused to carry a gun. In his own words he was inspired by Tolstoy. Nemrava was a member of the religious pacifist Nasaren sect.

For this repeated act of insubordination he was given two more years that he sat out in Terezín under harsh conditions. The case was widely reported all over Austria-Hungary and even reached Reichsrat.

Superarbitrated

After his second release from prison there is an interesting parallel to Švejk. On 15 November 1907 a military commission in Brno declared Nemrava insane and he was super-arbitrated (dismissed from the armed forces). Defence secretary in Cisleithania, Georgi, had the following answer when he was asked about the case in Reichsrat: he was released from duty because he was "psychopathic, twisted and suffered from weird perceptions".

During the spring of 1914 Nemrava again appears in newspaper columns, now as a "trader from Kroměříž". On this occasion he had refused to swear the oath to a civilian court in Olomouc!

The first world war

At the start of June 1915 Národni listy, Venkov and other newspapers wrote that Nemrava had turned around and now fought at the front with Infanterieregiment Nr. 54. The information was reportedly taken from a letter he sent to the newspaper Pozor in Olomouc.

On the other hand, several newspapers, including Prager Tagblatt in 1930, wrote that he persisted in his refusal to do military service also during the war and that he was imprisoned for three more years. These contradictory statements can not be clarified without access to his military documents (see the final paragraph).

Hašek and Nemrava

The few lines in The Good Soldier Švejk was not the first time that Jaroslav Hašek wrote about the famous conscientious objector from Moravia. In the story "The Nasarens" from 1908 the author mentions both the religious sect and Nemrava himself. It should also be added that censorship ensured that the story never was published. Hašek also notes that Nemrava was dismissed from the army due to madness.

Thief and dealer in stolen goods

His name reappears in the newspapers in 1924 and now it turns out that the idealist has turned into a criminal, although his official occupation was a trader. In the early 1920's he was involved in several major burglaries and is also a key person in pulling the threads and selling stolen goods.

In 1930 he is caught again, now as an art- and antique-dealer from Svatý Kopeček by Olomouc. He committed major fraud with valuable paintings and was handed a 6 month prison term. The case is widely reported, also in the national press.

Thereafter his traces disappear but church records reveal that he died in 1948 in Nová ulice, a suburb of Olomouc. The same source reveals that he was born on 6 May 1882 in house number 83 in Hněvotín, a village just south-west of Olomouc.

A well known conscientious objector

Nemrava was one of the first and best known people conscientious objectors and the case was noticed even abroad. Nemrava himself corresponded with Tolstoy's doctor and Karel Čapek, Klofáč and Professor Masaryk followed the case. Karl Liebknect had also noticed the events, and even in the French press a notice appeared. In 2009 the case was written about in the book Vojáku Vladimire by Zdeněk Bauer which amongst other sources is based on Mr. Čapek's correspondence. In 2014 the council of Hněvotín (Milan Krejčí) published a thorough article about the towns once famous son, largely extracts from Bauer's book.

Willy Nemrawa in Infanterieregiment Nr. 54

© VÚA

Access to military service record at VÚA (March 2018) sheds light on the conflicting information from Národní listy (1915) and Prager Tagblatt (1930). During the Territorial Army drafts (Landsturmmusterungen) in 1914 Nemrava was called up again. He was found fit for service on 22 November 1914 by the draft commission in Povel (now a suburb in the south of Olomouc), and enrolled in Infanterieregiment Nr. 54 as an arm-carrying Landsturminfanterist on 16 February 1915.

The documents don't contain any information about a new sentence and three years in prison. Rather the contrary: he was promoted to "Landsturm-Gefreiter" in 1916, which surely would not have happened if he was in prison. In his service record he is listed as Willy Nemrawa, but otherwise the details correspond to those found in the church records. It is also revealed that he was blond and small in stature (164 cm). His father was Josef Nemrava from Loučany and the mother Marie Kreuzer from Hněvotín. Nemrava spoke Czech, German and Polish. He was enlisted as a reserve in the Czechoslovak army on 21 December 1919.

Militarismus und Antimilitarismus, Karl Liebknecht, 1907

In Prag wurde eine Arbeiterakademie unter zahlreicher Beteiligung gegründet. Die nationalen Konflikte mit dem Militarismus (Sprachen-frage und die Vergewaltigung einzelner Soldaten) belebten die antimilitaristischen Tendenzen. Besonders hervorgehoben sei hier der Fall Nemravas, eines Soldaten, der sich weigerte, die Waffen zu tragen, und dafür bestraft wurde.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Před vojnou žil na Moravě nějakej pan Nemrava, a ten dokonce nechtěl vzíti ani flintu na rameno, když byl odvedenej, že prej je to proti jeho zásadě, nosit nějaký flinty. Byl za to zavřenej, až byl černej, a zas ho nanovo vedli k přísaze. A von, že přísahat nebude, že je to proti jeho zásadě, a vydržel to.“

Sources: VÚA, Zdeněk Bauer, Milan Krejčí

Literature

- NazarénštíJaroslav Hašek23.10.1908

- Geburts- und Tauchbuch für das Jahr 1882

- Interpellation1907

- Vilém Nemrava (1882–?)

- Josef Švejk mezi realitou a fikcí

- Odpírač Vilém Nemrava (1882-?)2014

- Militarismus und Antimilitariskus1907

- Verweigerung des Fahneneides9.12.1904

- Nováček odmítl přisahati23.12.1904

- Nepřítel zbraně28.6.1905

- Olomoucký Nazarén22.6.1907

- Případ Nemavrův22.6.1907

- Vojín Nemrava27.6.1907

- Der Nazarener Nemrava25.10.1907

- Voják, který nechce nositi zbraň14.4.1908

- Eidesverweigerung15.3.1914

- Známení doby2.6.1915

- Známka doby3.6.1915

- Vykrádali byty16.2.1924

- Obchody se ukradenými šperky17.2.1924

- Zpronevěřil za 342.000 Kč obrazů a starožitností4.6.1931

- Nasarener Nemrava wegen Bildbetruges verurteilt4.6.1931

- Konec Nemravův12.6.1931

| a | Nazarén ve vojště | 6.11.1904 |

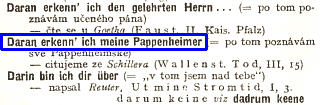

| zu Pappenheim, Gottfried Heinrich |  | ||||

| *8.6.1594 Treuchtlingen - †17.11.1632 Leipzig | ||||||

| ||||||

,1891

,1915

Pappenheim is mentioned by Auditor Ruller through the expression "we know our Pappenheimers".

Background

Pappenheim was field marshal of the Catholic League in the Thirty Years' War. He was known as a capable military leader but also for his brutality. He took part in the battle of Bílá Hora, and fell in the battle of Lützen. Pappenheim is buried in Strahovský klášter.

Quote from Schiller

The quote in The Good Soldier Švejk is from a drama by Schiller called Wallensteins Tod (The death of Wallenstein) from 1799[a]. The exact wording is Daran erkenn' ich meine Pappenheimer, and the sentence is laid in the mouth of the famous military leader Albrecht von Wallenstein (1583-1634).

Originally it was meant as a compliment to Pappeneheim's soldiers but over time it has become a derogatory expression, meaning roughly "I know what they are up to". The quote also appeared elsewhere in Czech literarture and reproduced to the letter[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Učitel si povzdechl: „Když ten pan auditor neumí dobře česky. Já už jsem mu to také podobným způsobem vysvětloval, ale on na mne spustil, že sameček od vši se jmenuje česky ,vešák’. ,Šádný fšivák,’ povídal pan auditor, ,vešák. Femininum, Sie gebildeter Kerl, ist ten »feš«, also masculinum ist »ta fěšak«. Wir kennen uns’re Pappenheimer.“

| a | Wallensteins Tod | ||

| b | O slávě herecké | 1879 |

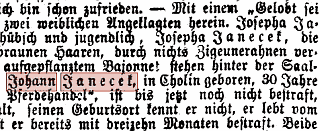

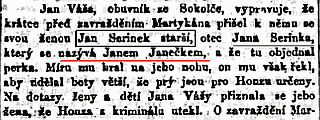

| Gipsy Janeček, Jan |  | ||||

| *19.10.1840 Chotína - †9.9.1871 Plzeň | ||||||

| ||||||

Jan Janeček. Zdroj: Archiv města Plzně, Místopisná sbírka Ladislava Lábka, kart. 60.

© Encyklopedie Plzeň

,22.9.1869

,25.5.1871

,31.5.1871

,9.9.1871

,10.9.1871

Janeček was according to Švejk a gypsy from Plzeň who in 1879 was sentenced to death for a double murder, had his execution postponed by a day due to the birthday of Emperor Franz Joseph I., then posthumously rehabilitated because it was discovered that the guilty was another Janeček. This is a story Švejk tells his fellow inmates in the arrest at Hauptwache in Brucker Lager.

Background

Janeček (real name Jan Serinek) was a criminal born near Plzeň who first hit the headlines in 1869 when he and three family members were sentenced to long prison terms for robbery and murder. The trial took place in c.k. zemský co trestní soud in September and the verdict was given on the 25th. The 30 year old Jan and his 18 year old brother Josef (sometimes quoted as cousin) were given 18 years. Two younger female family members (both named Josefa) were given five and four years respectively. The fifth gang member, the 45 year old bricklayer Andreas Holler, was given life imprisonment. In November the Janeček brothers were sent to Kartouzy to serve their sentence.

Escape, robbery and murder

On 24 April 1870 the brothers and a Polish gypsy, Franticzek Janeczka, managed to escape. Already the next night they committed three assaults in the area between Turnov and Jičín. Their first victims were three women who were brutally assaulted and robbed at two in the afternoon. This was the start of a rampage that left three people dead and numerous other's victims of theft, assault and robbery. The three escapees joined with other clan members and operated in various regions, amongst them the Poděbrady area and also around Plzeň. On 2 June they avoided an attempt to arrest them near Klatovy. The first murder was committed 9 August by Sokoleč, okres Poděbrady. The next murder took place 21 October by Strojetice (same district) and three days later yet another one: in Chrást near Plzeň. The latter two crimes were also robberies.

Arrest, trial and sentence

After six months on run, the gang was gradually rounded up and arrested in their home area east of Plzeň. Josef was arrested on 26 October in Horomyslická hospoda but Jan escaped through a window. He was finally caught four days later by Lhota on the southern outskirts of Plzeň. The trial took place in Plzeň at the end of May 1871. The accused numbered 11 in total and there was no less than 26 items on the list. The verdict was passed on the 31st and Janeček (Jan) was the only accused who was sentenced to death. Josef was handed a life sentence and the others between one and eight years in prison.

Execution

It took more than three months from the sentence was passed until the execution took place. After the final approval was given by the emperor, the outcome was communicated to Janeček on 7 September and there was also some delay due to disagreements with the executioner Piperger. In the morning of 9 September 1871 a huge crowd (tens of thousands) were gathered at the execution ground[a] and witnessed the last public execution in Bohemia during the time of Austria-Hungary.

Švejk mystifies

The good soldier had a less than adequate grasp of the facts in this anecdote. Janeček was executed in 1871, not in 1879. Nor was the execution postponed due to the emperor's birthday (18. august), and there was no questions of any posthumous rehabilitation due to the wrong man having been hanged.

Ich bin Serinek, ein Deutscher

In 1911 Jaroslav Hašek wrote a story about a Serinek "gypsy gang" that is obviously related to the executed criminal. There is however no direct connection to the events that Švejk describes in the novel. It is about a Serinek family of 18 who travel from village to village around Liberec (Reichenberg) and offer to register as Germans in return for money, beer and sausages[b]. Here the main character is Serinek, a senior clan leader. He can not have been identical to the executed person that Švejk talks about, but may have been his assumed father, also named Jan Serinek.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] „Zkrátka a dobře,“ řekl Švejk, „je to s vámi vachrlatý, ale nesmíte ztrácet naději, jako říkal cikán Janeček v Plzni, že se to ještě může vobrátit k lepšímu, když mu v roce 1879 dávali kvůli tý dvojnásobný loupežný vraždě voprátku na krk. A taky to uhád, poněvadž ho vodvedli v poslední okamžik vod šibenice, poněvadž ho nemohli pověsit kvůli narozeninám císaře pána, který připadly právě na ten samej den, kdy měl viset.

Literature

- Jan Janeček

- Vrah si zahrál karty a šel na poslední veřejnou popravu.9.9.2011

- Babinský, Janeček a jiní graselové3.4.2012

- Poslední veřejná poprava: Oběšence sledovaly davy, tělo se houpalo několik hodinMilan Kilián9.9.2021

- Jan Janeček5.1.2020

- Zločin, loupěžné vraždy, loupeže a krádeže.21.9.1869

- Raumord, Raub und Diebstahl20.9.1869

- Aus dem Rechtsleben27.9.1869

- Entflohene Sträflinge25.4.1870

- Die drei Ersprungenen Raubmördere7.5.1870

- Aus dem Böhmerwalde8.6.1870

- Die Janečeks19.8.1870

- Fluchtversuch der Janeček's26.1.1871

- Janečkové před soudem25.5.1871

- Výňatek z obžaloby Janačků25.5.1871

- Gebrüder Janeček und Komp. vor Gericht26.5.1871

- Aus dem Rechtsleben31.5.1871

| a | Poprava Jana Janečka | 10.9.1871 | |

| b | Ich bin Serinek, ein Deutscher | Jaroslav Hašek | 30.1.1911 |

| Servant Matěj |  | ||||

| ||||||

Panuška's servant was an expert on cow-shit resurrection plants

,1889

Matěj was the servant of painter Panuška who according to Švejk explained to an old lady what a Rose of Jericho looks like. He had by then already been mentioned indirectly.

Background

This figure is probably inspired by a real person because Hašek knew painter Panuška well in 1921 and 1922. Still, no person has been identified that fits the description. It can't even be ruled out (although the hypothesis is far-fetched) that Hašek degraded their common friend Zdeněk Matěj Kuděj to a servant of Panuška.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Tak na př. na otázku, proč se nepřizná, odpověděl dle protokolu: ,Já jsem zrovna v takový situaci, jako se voctnul jednou kvůli nějakejm obrazům panny Marie sluha akademického malíře Panušky. Ten taky, když se jednalo o nějaký vobrazy, který měl zpronevěřit, nemoh na to nic jinýho vodpovědět než: »Mám blít krev?«

[II.4] „To ale nebyla moje slova, to vykládal sluha malíře Panušky Matěj jedné staré bábě, když se ho ptala, jak vypadá růže z Jericha.

| Blacksmith Kříž |  | |||

| |||||

No blacksmith named Kříž was listed in the Prague address register.

,1907

Kříž appears when Sappeur Vodička tells an anecdote where he illustrates how nebulous he thinks Švejk's many stories are.

Background

This is a figure that is almost impossibe to find a "model" for. Kříž is a common surname[a] but no blacksmiths bearing this name are listed in the address book of Prague from 1907.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Když se ho auditor ptal, čím je v civilu, tak říkal: ,Dejmám u Kříže.’ A trvalo to přes půl hodiny, než auditorovi vysvětlil, že tahá měch u kováře Kříže, a když se ho potom zeptali: ,Vy jste tedy v civilu pomocnej dělník,’ tak jim odpověděl: ,Kdepak ponocnej, ten je Franta Hybšů.’“

| a | Příjmení: 'Kříž', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 |

| Night watchman Hybšů, Franta |  | |||

| |||||

KdeJsme.cz,2017

František Hybš (1868-1944), a politician that Jaroslav Hašek may have been aware of and degraded to night watchman.

Prager Presse,14.8.1938

Hybšů was a ponocný (night watchman) that Sappeur Vodička tells mentions in an anecdote as an apropos to Švejk's interminable deliberations. See blacksmith Kříž.

Background

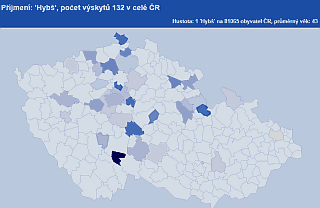

It has to date not been possible to identify any "prototype" for this figure (the name is a colloquial variation of František Hybš). Hybš is anyway a quite rare surname[a] and probably a Czech version of the German word hübsch (beautiful). See also Toníček Mašků.

The politician

František Hybš (1868-1944) was farmer and politician in the Agrarian Party[c]. He lived in Prague and Hašek may have been aware of him, and his peculiar way "demoted" him for literary purposes. See Břetislav Ludvík for a typical example of this technique.

Michal Giacintov

Podobné lidové "změny" jména jsem zaznamenal u babičky na Prácheňsku. Pravděpodobně se jedná o Františka Hybše = František Hybš. Je to tam v kraji běžné, já byl vnukem dědečka (Václav Onder) a byl jsem tam běžně nazýván Michal Ondrů. Tož tolik na vysvětlenou.

Miloslav Kilián

Jak víš, jsem z Jižních Čech, jejichž součástí je velká část bývalého historického kraje Prácheňského. A v minulosti bylo naprosto běžné a stále i dnes se to tak velmi často dělá, že se používá u jmen přivlastňovací způsob. Například - já jsem Míla Kilián. Ale běžně i dnes v našem jihočeském a částečně západočeském kraji ti řeknou - to je Míla Kiliánů. Ve smyslu - čí je Míla? Jakému patří rodu? Čí je? Míla je Kiliánů. Je jejich, je od nich, lidí z toho rodu, je Kiliánů. Patří jim. A používá se to často i u žen. Místo třeba Jana Kiliánová (už to samo o sobě vychází v českém jazyce z přivlastňovacího způsobu - je Kiliánova) se u nás řekne Jana Kiliánů. Také se i dnes můžeš běžnè setkat v našem kraji s ještě hovorovější variantou - Míla Kiliánouc. Pokud přivezu na naše akce mé kamarády z rodných Jižních Čech, třeba Zdeňka Nikodema i další, ten to i dnes běžně používá. "Byl tam Míla Kiliánů", nebo "Míla Kiliánouc". I já, jakmile přijedu k nám do Jižních Čech a přijdu tam mezi krajany, aniž si to uvědomuji, automaticky mi také přepne v hlavě jazyk a já to začínám také často používat. Na vesnicích to bylo ještě často i tak, že v jedné chalupě, či na jednom gruntě, žilo více lidí různých příjmení. Pak se stávalo, že třeba děti z té chalupy, i když mèly jiné příjmení po tátovi, v té vesnici jim říkali podle jména majitele chalupy. Já jsem například v prvních letech dětství žil s rodiči ve vesnici Buzice na chalupě mého dědečka, Františka Solara. A i když jsem byl po tátovi Kilián, v té vesnici mi nikdo jinak neřekl (a ještě nedávno, dokud žili pamětníci to tak bylo), než že jsem Míla Solarů. Čili od Solarů, z jejich chalupy.

Jaroslav Šerák

Myslím, že to Míla vysvětlil skvěle. Jen podotýkám, že totéž platilo i v jiných regionech. Mí kamarádi a spolužáci byli Josef Mašků (Mašek) z Prahy, Pepek Horálků (Horálek) z Chrudimska. Dědičná příjmení je poměrně mladá záležitost. Zavedl to dekretem až Josef II. v období 1780-1786. Do té doby se používalo tzv. nedědičné příjmí. Celý obor lze studovat zdeLR(b). Předpokládám, že Hybš - Hybšů má původ v německém hübsch - asi měl fešné předky.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Když se ho auditor ptal, čím je v civilu, tak říkal: ,Dejmám u Kříže.’ A trvalo to přes půl hodiny, než auditorovi vysvětlil, že tahá měch u kováře Kříže, a když se ho potom zeptali: ,Vy jste tedy v civilu pomocnej dělník,’ tak jim odpověděl: ,Kdepak ponocnej, ten je Franta Hybšů.’“

Sources: Jaroslav Šerák, Miloslav Kilián, Michal Giacintov

Literature

- Fr. Hybš 70 Jahre14.8.1938

| a | Příjmení: 'Hybš', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| b | Příjmí | Jana Pleskalová | 1.8.2023 |

| c | František Hybš |

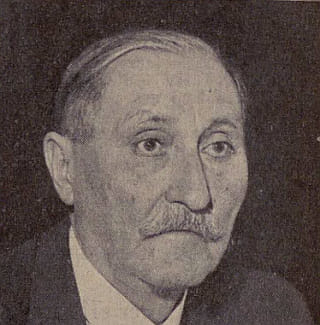

| Moudrá, Pavla |  | ||||

| *26.1.1861 Praha - †10.9.1940 Praha | ||||||

| ||||||

,1.2.1912

,25.4.1918

Pavla Moudrá is mentioned by Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek when he tells his fellow inmates at Hauptwache about how he got locked up for mutiny after refusing to clean the latrines.

Background

Pavla Moudrá was a Czech writer and translator (amongst them Victor Hugo, Twain, Kipling, H.G. Wells). She was also an early peace activist, animal rights activist and feminist, and briefly edited the journal Lada. She also contributed to the animal magazine Svět zvířat, for instance to the Christmas issue from 1911.

She was also active in the struggle against alcohol and lectured for the Czechoslovak abstinent's association together with Doctor Batěk and others[a]. Jaroslav Hašek also mentions here in a satirical story about the Salvation Army from 1921[b].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] A tak to šlo pořád: ,Budete pucovat?’ ,Nebudu pucovat.’ Hajzly lítaly sem a tam, jako by to bylo' nějaké dětské říkadlo od Pavly Moudré. Obršt běhal po kanceláři jako pominutý, nakonec si sedl a řekl: ,Rozvažte si to dobře, já vás předám divisijnímu soudu pro vzpouru. Nemyslete si, že budete první jednoroční dobrovolník, který byl za této války zastřelen.

Literature

| a | Lidovychovný odbor čsl. svazu abstinentního v Praze | 23.10.1919 | |

| b | Zápas s Armádou spásy | Jaroslav Hašek | 26.1.1921 |

| Supák Solpera |  | ||||

| ||||||

,4.7.1912

KdeJsme.cz,2017

,13.4.1912

Solpera was a contract soldier that Švejk that tells Sappeur Vodička about in an anecdote.

Background

Solpera is an extremely rare Czech surname[a]. IN Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 there is no trace of the name and nor is it mentioned in casualty lists from World War I. In Prague was in 1910 a single Solpera entered in the address book. He worked as an official at a coal magazine and lived in Smíchov.

Jindřichův Hradec

That said, the name appeared often enough in the newspapers of the time, and often in connection with Jindřichův Hradec. Karel Solpera was a long-time mayor of the town and the textile manufacturer Ignác Solpera also resided here. The well known graphics designer and writer Jan Solpera was born here in 1939 and has even had a font named after himself.

Supák

Supák was a colloquial term for a soldier who stayed on in the armed forces after completing his compulsory military service. The origin of the word is unclear. See also supák Schreiter.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] „Já jsem zas docela spokojenej,“ řekl Švejk, „to ještě před lety, když jsem sloužil aktivně, tak náš supák Solpera říkal, že na vojně musí bejt si každej vědom svejch povinností, a dal ti přitom takovou přes hubu, žes na to nikdy nezapomněl.

Literature

- Naše příjmení1894

| a | Příjmení: 'Solpera', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 |

| Oberleutnant Kvajser |  | ||||

| ||||||

K.u.k. Kriegsministerium,18.12.1914

KdeJsme.cz,2017

Kvajser was a late objrlajtnant who is mentioned in the same story as supák Solpera.

Background

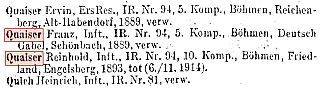

No person with the surname Kvajser lives in Czechia today. Phonetically closest is probably Kvaiser but this name is also very rare (17 persons). Somewhat more common is Quaiser with 45 persons living in Czechia in 2023[a]. The variant Quaisser also exists but is now (2023) very rare. Because this name is German it would surely have been much more common in the Czech lands before 1945.

Officers

Schematismus (k.u.k. Heer) from 1914 shows a reserve lieutenant Carl Quaiser from the Telegraphenregiment, a unit based in St. Pölten[b]. In k.k. Landwehr the reserve lieutentant Richard Quaiser served in III. Landesschützenregiment in Tyrol.

Casualty lists

The Verlustliste from World War I gives an indication where the name was most widespread. The lists reveal that the name almost exclusively was limited to a German speaking area of North Bohemia and was far more common than today. The two mentioned officers are however not on the lists so presumably they survived the war. On the other hand, many rank and file soldiers named Quaiser were killed, wounded or captured during the war[c].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Nebo nebožtík obrlajtnant Kvajser, když přišel prohlížet kvéry, tak vždycky nám přednášel, že každej voják má jevit největší duševní votrlost, poněvadž vojáci jsou jenom dobytek, kerej stát krmí, dá jim nažrat, napít kafé, tabák do fajfky a za to musí tahat jako volové.“

Literature

- Naše příjmení1894

| a | Příjmení: 'Quaiser', počet výskytů v celé ČR | 2017 | |

| b | Schematismus für das k.u.k. Heer (s. 967) | 1914 | |

| c | Verlustliste Nr. 81 | 18.12.1914 |

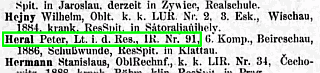

| Teacher Herál |  | ||||

| ||||||

© ÖStA

© ÖStA

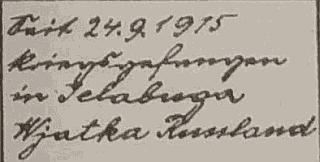

Nachrichten über Verwundete und Kranke ausgegeben am 1./5. 1915

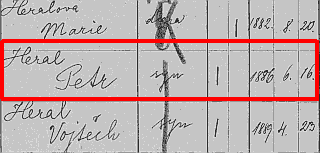

Sčítání lidu 1910, Boršov nad Vltavou

Herál was a teacher mentioned in yet another story that Švejk told Sappeur Vodička on the way to their interrogation by Auditor Ruller. During Švejk's compulsory military service Herál had explained the practices in military courts during the reign of Maria Theresa, that each regiment had its own executioner.

Background

One reserve lieutenant Petr Heral actually served in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 together with Jaroslav Hašek. He was born in 1886 with Heimatrecht in Boršov nad Vltavou and was promoted to Leutnant on 1 March 1915[b]. He was taken prisoner by the Russians on the same day as the author of The Good Soldier Švejk, at Chorupan 24 September 1915[a]. Hašek may thus have known Heral not only from IR. 91 but also from the three week prisoner transport to Darnytsia, maybe even further. The loss lists also reveal that he held a degree in law and that he served in the 6th company (i.e. in the 2nd battalion) at the time of his capture.

Whether or not he inspired the author to create the teacher Švejk tells about can obviously not be verified, but it remains an open possibility. If it could established that Heral actually was a teacher, it would be a near certainty.

The 1910 census

The census carried out in 1910 reveals more about Heral[c]. He was born in Boršov 16 June 1886 in house number 11, in a family of farmers, living there with three siblings and his mother Anna (b. 1851) who also owned the house. He is listed as single, Roman-Catholic and with Czech as his mother tongue. As usual in the census record it was stated that he could read and write. At the end of 1907 Heral was studying at C.k. vyšší realka in Budějovice and graduated that year. By 1910 he had completed a course at C.k. cejchovní úřad (gauging office) but at this stage there is no information about any employment.

This link to the gauging office facilitates further research. His obituary reveals that he was employed by the gauging office in Prague and that he returned from Russia (captivity) with malaria. The condition affected his heart and in the end this proved fatal. He died in Prague on 4 May 1938 and was buried in Boršov the next day[d].

Inconclusive

Heral is a rare surname (69 persons in Czechia in 2020)[f] so Hašek wouldn't have known many of them. That he knew Peter Heral from IR. 91 is very likely, but the latter was already working at the gauging office in 1913[e] so it is unlikely that he was also a teacher.

Other inspirations are possible but less likely than Peter Heral. In the Prague address book from 1910 only 2 Heral's are listed and they were not teachers. Nor do the police registers reveal any combination of name and occupation that fits.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] „Nic se neboj, Vodičko,“ konejšil ho Švejk, „jen klid, žádný rozčilování, copak je to něco, bejt před nějakým takovým divisijním soudem. Tos měl vidět, jak před lety se takový vojenský soud vodbejval zkrátka. Sloužil ti u nás v aktivu učitel Herál a ten nám jednou na kavalci vykládal, když jsme všichni v cimře dostali kasárníka, že je v pražským museu jedna kniha zápisů takovýho vojenskýho soudu za Marie Terezie. Každej regiment měl svýho kata, který popravoval vojáky svýho regimentu, kus po kusu, za jeden tereziánskej tolar. A ten kat podle těch zápisů vydělal si někerej den až pět tolarů.

Sources: Karl Wagner von Wagenried, Jan Ciglbauer

Literature

| Maria Theresa |  | ||||

| *13.5.1717 Wien - †29.11.1780 Wien | ||||||

| ||||||

,3.1.1910

Maria Theresa is mentioned by Švejk in the same story as teacher Herál.

Background

Maria Theresa was ruling archduchess of Austria, german-roman empress, queen of Hungary, queen of Bohemia and head of state of several other areas: Croatia, Galicia, Mantua etc.

Her father prepared the way for her ascension to the throne by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, also mentioned in the novel. This law gave women hereditary rights to the throne.

Maria Theresa introduced progressive reforms in the penal code and in education, but was also known for her anti-clerical attitudes. The fortress Terezín is named after her, and so is Theresianische Militärakademie. During her reign the empire was modernised and strenghtened.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Sloužil ti u nás v aktivu učitel Herál a ten nám jednou na kavalci vykládal, když jsme všichni v cimře dostali kasárníka, že je v pražským museu jedna kniha zápisů takovýho vojenskýho soudu za Marie Terezie. Každej regiment měl svýho kata, který popravoval vojáky svýho regimentu, kus po kusu, za jeden tereziánskej tolar. A ten kat podle těch zápisů vydělal si někerej den až pět tolarů.

Also written:Marie TerezieczMária Teréziahu

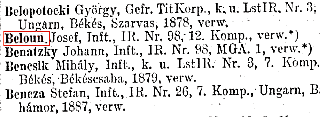

| Běloun |  | ||||

| ||||||

K.u.k. Kriegsministerium,13.10.1914

Běloun was a soldier who strangled a gipsy by the Drina after the latter had been caught with cigarettes he had received as a reward for hanging Serbian civilians. This is one of the stories Sappeur Vodička tells from his time at the front in Serbia.

Background

Neither Běloun nor the similar Beloun is found in contemporary databases of Czech surnames. Still, historical newspapers reveal that the name existed in 1914, but was very rare. In Verlustliste there is only one entry, a Josef Běloun from Infanterieregiment Nr. 98 who was wounded in 1914[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] „Když jsem byl v Srbsku,“ řekl Vodička, „tak u naší brigády věšeli, kteří se přihlásili, čúžáky za cigarety. Kerej voják pověsil chlapa, ten dostal deset športek, za ženskou a za dítě pět. Potom začlo intendantstvo spořit a vodstřelovalo se to hromadně. Se mnou sloužil jeden cikán a vo tom jsme to dlouho nevěděli. Bylo nám to jenom nápadný, že ho vždycky na noc někam volali do kanceláře. To jsme stáli na Drině. A jednou v noci, když byl pryč, tak někomu napadlo šťourat se v jeho věcech, a pacholek měl v ruksaku celý tři krabičky po stovce športek. Potom se vrátil k ránu do naší stodoly a my jsme s ním udělali krátkej soud. Povalili jsme ho a nějakej Běloun ho uškrtil řemenem. Měl ten pacholek tuhej život jako kočka.“

| a | Verlustliste Nr. 25 | 13.10.1914 |

| Auditor Ruller |  | ||||

| ||||||

,1930

,1913

Reichspost,24.8.1915

Ruller is mentioned 4 times in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Ruller was a prosecutor at Divisionsgericht who interrogated Švejk and Sappeur Vodička and reluctantly had to release them on orders from Oberst Schröder. Ruller is more interested in the drawings in a book by Fr. S. Kraus on the historical development of sexual morals than in performing his duties at the court.

The scene has similarities with the description of the judge in The Trial by Franz Kafka.

Background

With uncertainties aboubt what military courts existed in Brucker Lager it is even more difficult to establish if this figure has any real life counterpart.

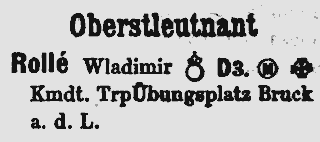

Wladimir Rollé

There is however another track to follow. The commander of the camp in 1915 was Oberstleutnant Wladimir Rollé (1860 - ?), a cavalry officer from Galicia who had been partly pensioned shortly before the war but served as commander of Brucker Lager at the same time[a]. This surname is well within margin of error with regards to Hašek's resuse of names. The rest is of course speculation.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Ztrápený voják učitel si přisedl na lavici a povzdechl: "To je všechno, a kvůli tomu jsem již počtvrté vyslýchanej u pana auditora."

[II.4] Učitel si povzdechl: "Když ten pan auditor neumí dobře česky.

[II.4] A jak to můžu splatit těm maďarskejm klukům, když sedím zavřenej, a ještě ke všemu se člověk musí přetvařovat a vykládat auditorovi, že nemá proti Maďarům žádnou zášť.

[II.4] Když se ho auditor ptal, čím je v civilu, tak říkal: ,Dejmám u Kříže.`

[II.4] V okovaných dveřích zarachotil klíč a vstoupil profous: "Infanterist Švejk a sapér Vodička k panu auditorovi."

[II.4] Sapér Vodička se zamyslil a po chvíli se ozval: "Až tam budeš, Švejku, u toho auditora, tak se nesplet, a co jsi předešle při výslechu mluvil, tak to vopakuj, ať nejsem v nějaký bryndě.

[II.4] Vstoupili právě do baráku s kancelářemi divisijního soudu a patrola je ihned odvedla do kanceláře čís. 8, kde za dlouhým stolem s haldami spisů seděl auditor Ruller. Před ním ležel nějaký díl zákoníku, na kterém stála nedopitá sklenice čaje. Po pravé straně na stole stál krucifix z napodobené slonoviny, se zaprášeným Kristem, který se zoufale díval na podstavec svého kříže, na kterém byl popel a oharky z cigaret. Auditor Ruller oklepával si právě k nové lítosti ukřižovaného boha novou cigaretu o podstavec krucifixu a druhou rukou nadzvedal sklenici s čajem, která se přilepila na zákoník. Vyprostiv sklenici z objetí zákoníku, listoval se dál v knize vypůjčené z důstojnického kasina. Byla to kniha Fr. S. Krause s mnohoslibným názvem „Forschungen zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der geschlechtlichen Moral“.

[II.4] "Was geht los?" otázal se, listuje dál a hledaje pokračování naivních kresbiček, skic a náčrtů. "Poslušně hlásím, pane auditor," odpověděl Švejk, "kamarád Vodička se nastyd a teď kašle." Auditor Ruller teprve teď se podíval na Švejka a na Vodičku.

[II.4] „Ty drž radši hubu,“ řekl auditor Ruller „až se tě na něco zeptám, tak teprv budeš odpovídat. Třikrát jsi byl u mne u výslechu a lezlo to z tebe jako z chlupatý deky. Tak najdu to nebo nenajdu? Mám já s vámi, vy chlapi mizerní, práci. Ale ono se vám to nevyplatilo, obtěžovat zbytečně soud.

Literature

- Kaisers Geburtstag in Brucker Lager24.8.1915

| a | Dienstbeschreibungen und Qualifikationslisten der Offiziere | 1761-1918 |

| Krauss, Friedrich Salomon |  | ||||

| *7.10.1859 Požega - †29.5.1938 Wien | ||||||

| ||||||

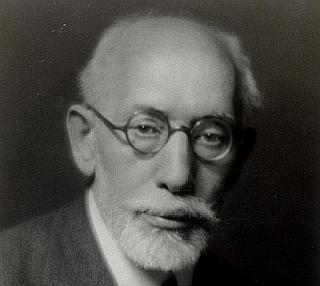

Porträt des Krauss, Friedrich Salomon [1859-1938]

© ÖNB

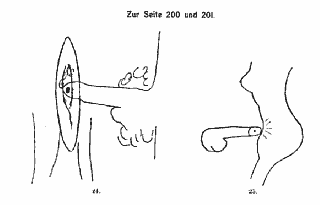

One of the naive drawings that auditor Ruller may have had a closer look at in Királyhida. Collected by Georges-Henri Luquet.

,1910

Krauss is mentioned because advocate Auditor Ruller is browsing his book Forschungen zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der geschlechtlichen Moral just as Sappeur Vodička and Švejk appear. He is studying some naive drawings of male and female reproductive organs, with suitable verses, as observed in the toilets at Berlin Westbahnhof by the learned Fr. S. Kraus himself.

Background

Krauss was a ethnographer, sexologist, folklorist, and Slavist of Croatian/Jewish origin, resident in Vienna. Early in his career he received funding from crown prince Crown Prince Rudolf for his ethnographic research amongst the south Slavs and later he worked with Sigmund Freud. He became a pioneer of "ethno-sexology", but a succession of obscenity trials hampered his work and had by 1913 ruined him financially.

The author is imprecise in describing Krauss and his publication. It was not a book, but rather a series of annual publications which appeared 10 times between 1904 and 1913. Krauss was the publisher of the series, not the author as Hašek suggests.

Anthropophyteia

The work in question is no doubt Anthropophyteia. Jahrbücher für Folkloristische Erhebungen und Forschungen zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der geschlechtlichen Moral. It was a series of scientific yearbooks, containing articles and studies from a number of scholars, and Krauss himself contributed some of it. The books were never publicly for sale, as they were intended for research only. The illustrations were limited to some pages at the end of each volume.

Drawings that fit the description Hašek gives in the novel are found in Vol. VII. (1910), page 529 to 535. They refer to a study published on pages 197 to 203, authored in French by Luquet[1]. He does not mention Berlin or any railway station toilet but in the same volume (p. 403) there is a section about scribbled verses in Berlin toilets (with examples). It may therefore be that Hašek composed the sequence from these two elements. In any case: nowhere in the ten volumes do we find drawings next to verses as described in the novel.

1. Georges-Henri Luquet (1876-1965). French philosopher and ethnologist. Pioneer on the research on children's drawings.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Vyprostiv sklenici z objetí zákoníku, listoval se dál v knize vypůjčené z důstojnického kasina. Byla to kniha Fr. S. Krause s mnohoslibným názvem „Forschungen zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der geschlechtlichen Moral“. Zadíval se na reprodukci naivních kreseb mužského i ženského pohlavního ústroje s přiléhajícími verši, které objevil učenec Fr. S. Krause na záchodcích berlínského Západního nádraží, takže neobrátil pozornost na ty, kteří vstoupili.

Also written:Fr. S. Krause/Fr. S. KrausHašekFranz S. KrauseParrott

Literature

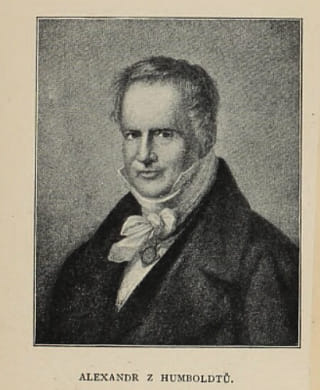

| von Humboldt, Alexander |  | ||||

| *14.7.1769 Berlin - †6.5.1859 Berlin | ||||||

| ||||||

Obrazy z přírody,1906

Notice about von Humboldt's death

Tagespost,10.5.1859

Humboldt is quoted by Einjährigfreiwilliger Marek when he gets the news that Švejk is off to the front in Galicia: In the whole world have I seen nothing more magnificent than this stupid Galicia.

The quote could also originate from his brother Wilhelm. It may also refer to Galicia in Spain, an area both Humboldt brothers visited.

Background

Humboldt (full name Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander Humboldt) was a famous German naturalist and explorer who undertook extensive research expeditions in Latin America and Central Asia. He is regarded as the co-founder of geography as empirical science. He was the brother of Wilhelm von Humboldt, founder of Berlin's Humboldt University.

Humboldt visited Galicia (Poland) in 1792/93 and Galicia (Spain) in 1799. It has however not been possible to connect him to Marerk's quote about Galicia.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Budete se v dálné cizině cítiti jako doma, jako v příbuzném kraji, ba skoro jako v milé domovině. S city povznesenými nastoupíte pouť do krajin, o kterých již starý Humboldt pravil: ,V celém světě neviděl jsem něco velkolepějšího nad tu blbou Halič.’

Literature

- Obrazy z přírody1906

- Sterbfälle10.5.1859

- von H. Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander1897

| Lawyer Bas, Otakar |  | ||||

| *21.3.1879 Hradec Kralové - †18.3.1939 Praha | ||||||

| ||||||

,26.4.1935

Bas is a lawyer who is mentioned by Švejk after he and Sappeur Vodička had been interrogated by Auditor Ruller. Bass told his clients that it was their duty to lie.

Background

Bas was a Czech radical lawyer who received his license in 1908 and specialised in defending opponents of the Habsburg regime. Already as a young candidate lawyer he was active in Sokol and also in politics. After the war he at one stage held the post as Vice President of the Czechoslovak Senate. He committed suicide shortly after the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

That this is the person the novel refers to is information provided from Antonín Měšťan. He is almost certainly right as minor spelling mistakes like Bas-Bass are quite common throughout The Good Soldier Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.4] Já jsem se u vejslechu, to je pravda, vymlouval všelijak, to se musí dělat, to je povinností lhát, jako říká advokát Bass svým klientům.

Also written:BassHašek

Literature

- Veřejná schůze lidu v Nových Dvorech12.9.1902

- Uctění památky Karla Havlíčka Borovského27.6.1906

- Advokáti17.7.1908

|

II. At the front |

| |

4. New afflictions | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 14.5.2024 |