Mariánská kasárna in CB (Budweis). Until 1 June 1915 it was the home of the Good Soldier Švejk's Infanterieregiment Nr. 91. In 1915 Jaroslav Hašek also served with the regiment in these barracks.

The novel The Good Soldier Švejk refers to a number of institutions and firms, public as well as private. On these pages they were until 15 September 2013 categorised as 'Places'. This only partly makes sense as this type of entity can not always be associated with fixed geographical points, in the way that for instance cities, mountains and rivers can. This new page contains military and civilian institutions (including army units, regiments etc.), organisations, hotels, public houses, newspapers and magazines.

The line between this page and "Places" is blurred, churches do for instance rarely change location, but are still included here. Therefore Prague and Vienna will still be found in the "Places" database, because these have constant coordinates. On the other hand institutions may change location: Odvodní komise and Bendlovka are not unequivocal geographical terms so they will from now on appear on this page.

The names are colour coded according to their role in the plot, illustrated by these examples: U kalicha as a location where the plot takes place, k.u.k. Kriegsministerium mentioned in the narrative, Pražské úřední listy as part of a dialogue, and Stoletá kavárna, mentioned in an anecdote.

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all

Institutions index of institutions, taverns, military units, societies, periodicals ... (288)

Show all I. In the rear

I. In the rear  14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14)

14. Švejk as military servant to senior lieutenant Lukáš (14) II. At the front

II. At the front  1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15)

1. Švejk's mishaps on the train (15) 2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38)

2. Švejk's budějovická anabasis (38) 3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44)

3. Švejk's happenings in Királyhida (44) 4. New afflictions (26)

4. New afflictions (26)

|

II. At the front |

| |

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal | |||

| 11. Marschkompanie |  | ||||

| ||||||

An example of the confusion that the term march company caused in the early years of Hašek research.

,1959

11. Marschkompanie becomes the scene of the plot in [II.5] in Királyhida but the unit has already been mentioned, using the more ambiguous wording 11. Kompanie. The author freely mixed the terms 11th company and 11th march company, but from the context of The Good Soldier Švejk, it is clear that he always had the 11th march company in mind.

Commander of the company is Oberleutnant Lukáš who had, in his own words, "inherited" the company, unknown from who. The company reported to an unspecified march battalion that was commanded by Hauptmann Ságner.

Background

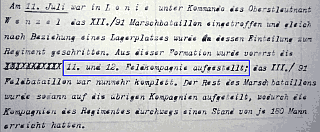

11. Marschkompanie never existed as a unit in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in 1915. The number 11 the author evidently borrowed from the 11th field company in which he served as a soldier from 11 July until 24 September 1915. From 1 June until arriving at the front he had belonged to the 4th march company of XII. Marschbataillon of IR91. Like most other march units it was dissolved soon after arriving at the front.

Confusion of terms

Early experts on Hašek like Zdena Ančík believed that because Švejk served in the 11th march company the same must necessarily have been the case with his creator.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Nadporučík Lukáš chodil rozčileně po kanceláři 11. maršové roty. Byla to tmavá díra v baráku roty, přepažená z chodby prkny. Stůl, dvě židle, baňka s petrolejem a kavalec.

[II.5] To je jedenáctá marškumpanie, kterou jsem zdědil. Co z nich mohu udělat? Jak si budou počínat v opravdovém gefechtu?

[II.5] Vypravoval nedávno štábsfeldvébl Hegner, že příliš neladíte s panem hejtmanem Ságnerem a že on právě pošle naši 11. kumpačku první do gefechtu na ta nejhroznější místa."

[II.5] Nadporučík Lukáš otočil se na židli ke dveřím a zpozoroval, že se dveře pomalu a tiše otvírají. A stejné tak tiše vstoupil do kanceláře 11. marškumpanie dobrý voják Švejk, salutuje již ve dveřích a patrně již tenkrát, když klepal na dveře, dívaje se na nápis "Nicht klopfen!"

[II.5] Švejk pohyboval se tak volně společensky v kanceláři 11. marškumpanie, jako by byl s Vaňkem nejlepším kamarádem, na což účetní šikovatel reagoval prostě slovy: "Položte to na stůl."

[II.5] Já jsem totiž zde ordonanc," řekl hrdě dodatkem, "pan obršt Schröder mě sem přidělil k 11. marškumpačce k panu obrlajtnantovi Lukášovi, u kterého jsem byl pucflekem, ale svou přirozenou inteligencí jsem byl povýšenej na ordonanc.

[II.5] Kdo je u telefonu? Ordonanc od 11. marškumpanie. Kdo je tam? Ordonanc od 12. maršky? Servus, kolego. Jak se jmenuji? Švejk. A ty? Braun.

Literature

- "Rodokmen" či spíše "vývod" lajtnanta Duba, Karel Dub,2009

| 10. Marschkompanie |  | ||||

| ||||||

,1927

10. Marschkompanie is mentioned by Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk i [II.5] when he chatters away to Oberleutnant Lukáš when he was with this company at the front by Dukla and how incompetent Hauptmann Ságner had proven to be.

The unit has already been mentioned in the previous chapter, using the more ambiguous wording 10. Kompanie.

Background

10. Marschkompanie never existed as a unit in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in 1915. The number ten is no doubt borrowed from 10. Feldkompanie, a pattern that repeats itself with all the companies from IR. 91 that are mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Mystifications

As little as any 10th march company existed could Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk ever have served with them in the area around Dukla. Three battalions of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 operated 100 kilometres to the east, in Východní Beskydy. They were deployed in this area from mid February until early May 1915.

Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk also claims that Hauptmann Ságner took part in the operations by Dukla. This may have been true for Hašek's literary figure but not for his real-life counter-part Čeněk Sagner. The latter was wounded in Serbia in November 1914 and only returned to front duty in June 1915, and now much further east, in the area south of Lemberg.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Účetní šikovatel si vzdychl: „Já bych byl toho náhledu, že v takové válce, jako je tahle, kdy je tolik vojska a taková dlouhá fronta, že by se spíš mohlo docílit víc jenom pořádným manévrováním nežli nějakými zoufalými ataky. Já to viděl pod Duklou při 10. marškumpačce. Tenkrát se to všechno odbylo úplně hladce, přišel rozkaz ,Nicht schießen’, a tak se nestřílelo a čekalo, až se Rusové přiblížili až k nám. Byli bychom je zajali bez výstřelu, jenomže tenkrát měli jsme vedle sebe na levém flanku ,železné mouchy’, a ti pitomí landveráci tak se lekli, že se k nám Rusové blíží, že se začali spouštět dolů ze strání po sněhu jako na klouzačce, a my jsme dostali rozkaz, že Rusové protrhli levý flank, abychom se hleděli dostat k brigádě. Já byl tenkrát právě u brigády, abych si dal potvrdit kompanieverpflegungsbuch, poněvadž jsem nemohl najít náš regimentstrain, když vtom začnou k brigádě chodit první z 10. maršky. Do večera jich přišlo sto dvacet, ostatní prý po sněhu sjeli, jak při ústupu zabloudili, někde do ruských štelungů, jako by to byl tobogan. Tam to bylo hrozné, pane obrlajtnant, Rusové měli v Karpatech štelungy nahoře i dole. A potom, pane obrlajtnant, pan hejtman Ságner...“

Literature

| Offiziersmenage |  | ||||

| Királyhida, Lagerstrasse | ||||||

| ||||||

Offiziersmenage im Lager

,26.5.1912

Offiziersmenage is by Oberleutnant Lukáš when he complains to Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk that he sent Offiziersdiener Baloun here to get him lunch but the latter ate half of it.

Background

Offiziersmenage (Officers' mess) refers to an officer's dining rooms in Brucker Lager. There is no doubt that it existed[a], perhaps there were several both in the old and the new camp. In this case it would surely have been a mess in Altes Lager where Hašek himself served. We don't know where the mess(es) was located but it would surely have been along Lagerallee or not far from it.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] "Vybral jste mně opravdu znamenitého pucfleka," mluvil nadporučík Lukáš k účetnímu šikovateli, "děkuji vám srdečně za to milé překvapení. První den si ho pošlu pro oběd do oficírsmináže, a on mně ho půl sežere."

Credit: Klara Köttner-Benigni

Also written:Officers' messenOffisersmessano

Literature

| a | Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich | 1983 |

| Brucker Einjährigfreiwilligenschule |  | |||

| Bruck an der Leitha, Alte Wiener Straße 36 | |||||

| |||||

Bruck, Alte Wiener Straße - Landwehrkaserne ca.1915

,1913

Brucker Einjährigfreiwilligenschule is mentioned by Oberleutnant Lukáš when he in a conversation with Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk complains over having been given the command of 11. Marschkompanie, a completely hopeless unit. It is also revealed that Hauptmann Ságner commanded the school during night exercies but had got lost and only stopped when they reached the mud by Neusiedler See.

Background

Brucker Einjährigfreiwilligenschule refers to the reserve officer's school in Bruck an der Leitha. It was located in Landwehrkaserne in the western part of town. The building is still intact and in 1983 it was occupied by council houses[b].

Some time after Ersatzbataillon IR. 91 was moved to Bruck-Királyhida (1 June 1915) the reserve officer's schools from the various units in the garrison were merged. The 14th course started in April 1917[a]. See also Budweiser Einjährigfreiwilligenschule.

Quote(s) from the novel

[IV.5] „Předevčírem při nachtübungu měli jsme, jak víte, manévrovat proti Einjährigfreiwilligen Schule za cukrovarem. První švarm, vorhut, ten šel ještě tiše po silnici, poněvadž ten jsem vedl sám, ale druhý, který měl jít nalevo a rozeslat vorpatroly pod cukrovar, ten si počínal, jako kdyby šel z výletu.

[IV.5] A to nevíte, pane obrlajtnant, že při tom posledním nachtiibungu, o kterém jste vypravoval, einjährigfreiwilligenschule, která měla naši kumpačku obejít, dostala se až k Neziderskému jezeru?

Credit: Josef Novotný

Literature

- Z mých válečných pamětí, ,2021 [a]

- Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich, ,1983 [b]

- Militär-Adressbuch für Wien und Umgebung, ,1913

| a | Z mých válečných pamětí | 2021 | |

| b | Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich | 1983 |

| Brucker Zuckerfabrik |  | |||

| |||||

Zuckerfabrik 1910

,31.1.1909

Brucker Zuckerfabrik is mentioned by Oberleutnant Lukáš, through the term "sugar factory" when he tells Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk about some manouvres he took art in behind the factory.

Background

Brucker Zuckerfabrik (Bruck Sugar Factory) refers to a sugar factory in Bruck and der Leitha that started production in 1909. It was owned by Österreichischen Zuckerindustrie-Aktiengesellschaft until 1931 and had several owners throughout the years. Until it was closed in 1986 it remained one of the largest sugar refineries in Austria. Wolfgang Gruber and Erwin Sillaber have written a detailed history of the sugar factory[a]. Today the building is occupied by a biodiesel factory.

The Good Soldier Švejk in Captivity

The factory is mentioned also in Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí but is erroneously placed in Királyhida.[1]

Jinak Királyhida je zaprášené město. Obyvatelé nevědí, jestli jsou Němci nebo Maďaři. Městské děvy pěstují flirt s důstojníky vojenského tábora z Brucku. Také tu kvete prostituce jako všude v Maďárii. Jsou tam jen dvě památnosti, zříceniny cukrovaru a vykřičený dům U kukuřičního klasu, který ráčil poctíti svou návštěvou arcivévoda Štěpán roku 1908 za velkých manévrů.

Wolfgang Gruber

Trotz regionaler Widerstände und Schwierigkeiten entstand in Bruck im Jahre 1909 ein moderner Verarbeitungsbetrieb für Zuckerrüben. Die Brucker Zuckerfabrik wurde für die Ostregion südlich der Donau über Jahrzehnte zu einem wichtigen Arbeit- und Auftraggeber.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Předevčírem při nachtübungu měli jsme, jak víte, manévrovat proti Einjährigfreiwilligen Schule za cukrovarem. První švarm, vorhut, ten šel ještě tiše po silnici, poněvadž ten jsem vedl sám, ale druhý, který měl jít nalevo a rozeslat vorpatroly pod cukrovar, ten si počínal, jako kdyby šel z výletu.

Credit: Wolfgang Gruber

Also written:Bruck Sugar FactoryenBruck cukrovarczBruck sukkerfabrikkno

Literature

- Die Brucker Zuckerfabrik, [a]

- Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich, ,1983

- Die neue Zuckerfabrik in Bruck, ,31.1.1909

- Zur Tage der Böhmischen Maschinenfabriken, ,16.7.1909

- Der Fabriksbrand in Bruck an der Leita, ,11.8.1916

- Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí, ,1917 [1]

| a | Die Brucker Zuckerfabrik | ||

| 1 | Dobrý voják Švejk v zajetí | 1917 |

| 9. Marschkompanie |  | |||

| |||||

IR. 91/9. Feldkompanie captured on 22 March 1915.

,1915

Lieutenant Ladislav Kvapil was one of eight officers from IR. 91 who were taken prisoner on 22 March 1915.

Captain Viktor Wessely, taken prisoner on 22 March 1915.

© ÖStA

9. Marschkompanie is mentioned by Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk when he tells Oberleutnant Lukáš about his experiences at the front. This company was according to him the worst of them all and were at one stage captured as a unit, together with its commander.

Background

9. Marschkompanie never existed as a unit in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in 1915. The number nine is evidently borrowed from 9. Feldkompanie, a pattern that repeats itself with all the companies from IR. 91 that are mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Entire companies captured

That entire companies (appx. 180 men) were captured didn't happen often with Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 but during the retreat from Serbia in December 1914 three companies "disappeared". According to Jan Eybl the 5th, 14th and 15th company were captured[a]. Hašek was surely aware of these events and may at least hypothetically have knitted it into the novel.

Disaster in the Eastern Beskids

That said, events in Východní Beskydy on 22 March 1915 provide more solid clues. During a Russian attack in the early hours, large parts of 9. Infanteriedivision were caught in their sleep and captured. Worst hit was Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 and IR73 and both regiments lost entire companies. III. Feldbataillon was nearly wiped out and three of its four companies were captured. These were the 9th, 10th and 12th and the 11th was severely decimated. Who the commander of 9. Feldkompanie was at the time is not known. Jan Eybl noted that the "lieutenant of the company" and 20 men fell asleep on guard and this lieutenant may well have been the company commander. 11. Feldkompanie was subjected to investigations after the battle and also on other occasions the company had come under scrutiny[b].

The Verlustliste of Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 for the 22 and 23 of March contains almost 600 names, and most of them are listed as "taken prisoner". Amongst those captured were the captains Franz Wild and Viktor Wessely, the lieutenants (Ladislav Kvapil and Viktor Dostal), and the reserve lieutenants (Karel Výška, Rudolf Förster, Josef Richter, and Johann Trapl)[c]. Hauptmann Wessely was almost certainly the commander of III. Feldbataillon as this had been his position during the campaign in Serbia a few months earlier. To which units the other officers belonged has not yet been ascertained, but it can be stated with near certainty that all the officers of 9. Feldkompanie were amongst those captured.

Considering that III. Feldbataillon ceased to exist, and the 9th company was captured with its officers, it is very likely that the regiment's collapse in the Carpathians inspired Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk's words to Oberleutnant Lukáš. Such a disaster would have been known by everyone in the regiment and Hašek would defintely have picked up some of the details.

Jan Ev. Eyvl

22.3. Ráno hned padla Malá Zolobona a tři setniny (9,10 a 12) zajaty. Úplně překvapeni o ½ 6 ráno. Poručík 9. setniny a všech 20 mužů usnulo na stráži.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] A všechny marškumpačky byla jedna jako druhá, žádná nebyla o chlup lepší než vaše, pane obrlajtnant. Nejhorší byla devátá. Ta s sebou odtáhla do zajetí všechny šarže i s kompaniekomandantem.

Literature

- První světová válka v denících feldkuráta P. Jana Evangelisty Eybla, I., ,2014 [a]

- První světová válka v denících feldkuráta P. Jana Evangelisty Eybla, II., ,2015 [b]

- Seznamy ztrát - 91. pěší pluk, ,2021 [c]

- Die russische Gegenoffensive, Maximilian Hoen,1939 [d]

| Drogerie Kokoška |  | ||||

| Praha I./360, Na Perstyně 4 | ||||||

| ||||||

,1892

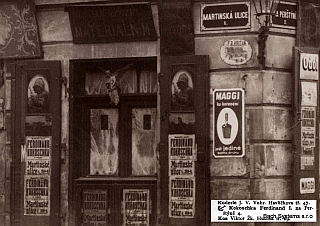

2.1.1905. Pohled na dům čp. 360 (U Tří zlatých koulí) na nároží ulic Martinské a Na Perštýně na Starém Městě těsně před zbořením roku 1905.

© AHMP

,1.7.1890

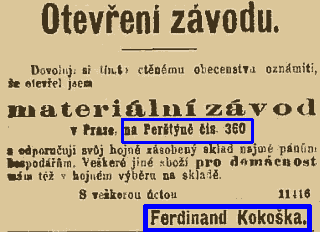

Drogerie Kokoška is mentioned during the first conversation between Švejk and Rechnungsfeldwebel Vaněk. The former he tells an anecdote about his time as a chemist's apprentice by Mr. Kokoška in Na Perštýně.

Background

Drogerie Kokoška was a chemist's store where Jaroslav Hašek in 1898 worked as an apprentice after prematurely ending his studies at the gymnasium. The shop was located at the corner of Na Perštýně and Martinská ulice, in the house U třech zlatých koulí. The information is confirmed by newspaper adverts, address books and a photo from 1905. The owner Mr. Kokoška opened the store/workshop in the summer of 1890. It was operating until 1906 when the proprietor died.

From the old pharmacy

The author's time at the chemists inspired a series of eight stories that were published in Veselá Praha in 1909 and 1910. Here Kokoška, Tauchen and Ferdinand all appear but the former two with their names slightly twisted but easily recognizable (Kološka and Tauben). The stories were translated into English by Cecil Parrott and were included in the book The red commissar.

The stories that are written in the first person form describe the pharmacy, the people who worked there, and also customers and neighbours. Pivotal to the story is Mr. Kološka who is an elderly man with a kind heart. His assistant is the lazy Mr. Tauben who doesn't take his duties too seriously and also encourages the young apprentice Hašek not to run his shoes off for the boss. Another employee is Ferdinand who is known for his colourful and immaculately kept carriage into which he puts all his diligence and pride. Mrs. Kološka is described in extremely unflattering terms and she is also given the nick-name "acid". She torments her husband and the staff at the pharmacy. Her name is Marie (born Vanouš), she is a tall and corpulent lady but with quite attractive features. She and her father continuously remind Kološka that the business would have gone under by now if it hadn't been for their help. It is also revealed that Kološka and his wife live together with the evil father-in-law and that the marriage came about for financial reasons. They lived somewhere else, not in the pharmacy building, and appeared to be quite well off.

Ficton and facts

Throughout Hašek's writing one will find a mix of facts, half-facts and invention, and so it is here. Starting with the facts: that the author was an apprentice at the pharmacy is beyond dispute, the owner was indeed Mr. Kokoška and the location of the business is precisely where Švejk puts it. Václav Menger also confirm that a Tauben worked there, likewise a Ferdinand Vavra who probably is the model of the Ferdinand with the colourful cart. On the other had the apprentice seem to have had a much more strained relationship with Tauben than what is apparent from the stories. The young Hašek was subjected to some envy from other staff members because he was capable and thus became a favourite of the boss. Further Václav Menger mentions Mrs. Kokošková and that she came from a wealthy background. This appears to be true but otherwise her biographical details are differ from those of her literary counterpart. From population registers we know that Mrs Kokošková was born Anna Milnerová in 1857 and not Marie Vanouš as in the stories.

As Hašek stated, the family didn't live on the premises of the pharmacy. Their address was Praha II., Pštrossová ul. 221/25. Here they are registered from 1880 and the next year their daughter Anna was born, so moving there was clearly a result of the marriage. Hašek may also have been touching real life when describing the obnoxious behaviour of Mrs. Kološková: Anna Kokošková eventually died in a lunatic asylum in Prague. On the other hand Tauben (or Tauchen) is a mystery. Despite Václav Menger's claim that he existed there is not a single Tauben to find in population records or police registers, and the few Tauchen who are listed have no obvious link to Kokoška or any pharmacy.

Aftermath

After the death of Mr. Kokoška in 1906 the shop and the workshop was taken over by Václav Rubeš. In the meantime it had also moved from No. 360 to the next-door No. 359 with address Martinská ulice. Anna Kokošková died as late as 1916, 59 years old. It is not known what happened to the daughter Anna who was 26 when her father died.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Já jsem se taky učil materialistou,“ řekl Švejk, „u nějakýho pana Kokošky na Perštýně v Praze. To byl náramnej podivín, a když jsem mu jednou vomylem ve sklepě zapálil sud benzinu a von vyhořel, tak mne vyhnal a gremium mne už nikde nepřijalo, takže jsem se kvůli pitomýmu sudu benzinu nemoh doučit. Vyrábíte také koření pro krávy?“

Also written:Drogerie Kokoschkade

Literature

- Adresář královského hlavního města Prahy a obcí sousedních, ,1907

- Ferdinand Kokoschka, ,1892

- Ferdinand Kokoška & spol.,

- Sterbefall, ,18.2.1906

- Převzeti závodu, ,4.10.1906

- Z droguerie, Jaroslav Hašek,24.3.1904

- Ze staré drogerie, Jaroslav Hašek,1909 - 1910

- Hašek inteligentním praktikantem, Václav Menger,2.7.1933

- Hašek si loučí s drogerií, Václav Menger,9.7.1933

| U milosrdných |  | |||

| Praha I./847, U milosrdných 1 | |||||

| |||||

1915 • Celkový pohled na klášter Milosrdných bratří (dům čp. 847) na Starém Městě.

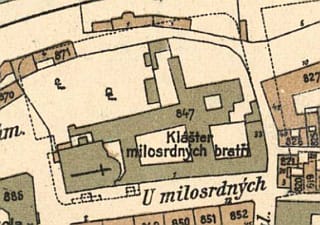

1909-1914 • Orientační plán král. hl. města Prahy a obcí sousedních

U milosrdných is mentioned by Švejk in his story from when he was a chemist's apprentice at drogerie Kokoška.

Background

U milosrdných refers to the hospital Nemocnice na Františku associated with the monastery complex klášter milosrdných bratří s kostelem sv. Šimona a Judy in Staré město.

The hospital has a history that goes back almost 700 years and is functioning to this very day (2024). The hospital was the first in Europe to carry out an amputation of limbs under full anaesthesia (1847). In 1997 a major reconstruction started but was complicated by the disastrous floods of 2002[a].

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Chytal holuby na půdě, uměl votvírat pult s penězma a ještě nás učil jinejm melouchům se zbožím. Já jako kluk jsem měl doma takovou lékárnu, kterou jsem si přines z krámu domů, že ji neměli ani ,U milosrdnejch’. A ten pomoh panu Tauchenovi; jen řek: ,Tak to sem dají, pane Tauchen, ať se na to kouknu,’ hned mu poslal pan Tauchen pro pivo.

Also written:U milosrdnejchŠvejk

Literature

- Historie nemocnice, ,2022 [a]

| a | Historie nemocnice | 2022 |

| 12. Marschkompanie |  | ||||

| ||||||

12. Feldkompanie reconstituted on 11.7.1915.

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien.,1927

12. Marschkompanie is mentioned when Švejk as the newly appointed messenger of 11. Marschkompanie is in a phone conversation with his colleague Braun from the 12th March Company.

The unit has already been mentioned in the previous chapter, using the more ambiguous wording 12. Kompanie. Hašek freely mixed the terms company and march company, but from the context of The Good Soldier Švejk it is clear that he always had the 12th march company in mind.

Background

12. Marschkompanie never existed as a unit in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in 1915. The number twelve is no doubt borrowed from 12. Feldkompanie, a pattern that repeats itself with all the march companies from IR. 91 that are mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk. See also 12. Kompanie.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Vaněk? Ten šel do regimentskanceláře. Kdo je u telefonu? Ordonanc od 11. marškumpanie. Kdo je tam? Ordonanc od 12. maršky? Servus, kolego. Jak se jmenuji? Švejk. A ty? Braun.

[II.5] Až budeš tedy něco vědět, tak nám to k 12. marškumpačce zatelefonuj, ty zlatej synáčku blbej. Vodkuď jseš?

Literature

| 13. Marschkompanie |  | ||||

| ||||||

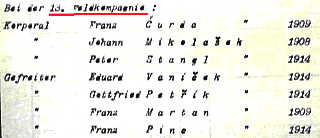

Some of the soldiers in the 13th field company, July 1915.

Das Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 am Vormarsch in Galizien.,1927

13. Marschkompanie is mentioned when Švejk, the newly appointed messenger of 11. Marschkompanie, is in a phone conversation with his colleague Braun from 12. Marschkompanie.

Background

13. Marschkompanie never existed as a unit in Infanterieregiment Nr. 91 in 1915. The number thirteen is no doubt borrowed from 13. Feldkompanie, a pattern that repeats itself with all the march companies from IR. 91 that are mentioned in The Good Soldier Švejk.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Tak vidíš, náš tam šel taky a vod 13. maršky taky; právě jsem mluvil s ordonancem vod ní po telefonu. Mně se ten kvalt nelíbí. A nevíš nic, jestli se pakuje u muziky?“

Literature

| Plynární stanice Letna |  | ||||

| Praha VII./138, U Královské Obory 37 | ||||||

| ||||||

Plynární stanice Letna is mentioned in the story about gas worker Zátka.

Background

Plynární stanice Letna refers to a gas station at Letná of which there were two in 1910. Both were guard-houses (strážnice) whose main duty was the street-lighting. The most obvious candidate is situated on the Letná plain, in U Královské Obory 138 (now Nad Královskou oborou 138/37), but the station in Skuherského 724/32 (now Pplk. Sochora 724/30) can not be ruled out entirely.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] „Co se mý osoby týká, pane rechnungsfeldvébl, když jsem to slyšel, co vy jste vo těch outvarech povídal, tak jsem si vzpomněl na nějakýho Zátku, plynárníka; von byl na plynární stanici na Letný a rozsvěcoval a zas zhasínal lampy.

| Kostel svaté Kateřiny |  | |||

| |||||

Kostel svaté Kateřiny is mentioned in the same story as Rekrut Pech who was from nearby Dolní Bousov where this church is.

Background

Kostel svaté Kateřiny is the parish church in Dolní Bousov. According to local sources it was built in 1759 and 1760 in baroque style. There was probably a church there already, just as Rekrut Pech says.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Dolní Bousov, Unter Bautzen, 267 domů, 1936 obyvatelů českých, hejtmanství Jičín, okres Sobotka, bývalé panství Kosť, farní chrám svaté Kateřiny ze 14. století, obnovený hrabětem Václavem Vratislavem Netolickým, škola, pošta, telegraf, stanice české obchodní dráhy, cukrovar, mlýn s pilou, samota Valcha, šest výročních trhů.’

| Church of Saint Sava |  | |||

| |||||

The first church of St. Sava, 1895

Church of Saint Sava is mentioned because the entire 6th March Company got lost here during the withdrawal from Belgrade. This is brought up in connection with the trial of Zugsführer Teveles.

Background

Church of Saint Sava at first glance seems to refer to the largest and most important cathedral in Serbia, and the largest cathedral in south-eastern Europe, and also the largest orthodox cathedral in the world.

This assumption is however wrong, because in 1914 the cathedral was still only being planned. Construction started as late as 1935, but in 1914 there was a small church with the same name on the site, and this is surely the one the author has in mind. Both churches were/are located on the Vračar hill.

The missing march company

The story about the missing 6th March Company may be based on real events although this company never existed (each march battalion consisted of four companies, numbered I,II,III and IV). The author may however had IR. 91/6th field company or another company of IR. 91 in mind. These fought by Belgrade during the withdrawal from Serbia in the week before 15 December 1914. During this time the regiment lost three entire companies before the remainder pulled out to Hungary across the river Sava. The three missing field companies (5th, 13th and 14th) were however captured by Borak south of Belgrade, not in the city itself.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Byl-li však pěšák Teveles povýšen v bělehradské válečné kampani za četaře, nedalo se naprosto zjistit, poněvadž celá 6. marškumpanie se ztratila u cerkve sv. Sávy v Bělehradě i se svými důstojníky.

Credit: Rudolf Kießwetter, Petr Novák

Also written:Cerkev svaté SavyHašekKostel svaté Savyczцрква Светог Савеsr

Literature

| Zur weißen Rose |  | |||

| |||||

Zur weißen Rose is mentioned because this is where Gefreiter Peroutka was found when the company was about to depart for the front.

Background

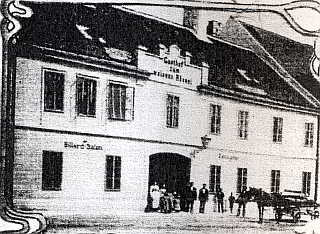

Zur weißen Rose (At the White Rose) has not been identified, but may be a mistranslation or misspelling of Zum weißen Rössel, a former guest-house in Bruck. Zum weißen Rössel was located in Altstadt 6, and on the first floor was a Mannschaftspuff (brothel for the lower ranks). Altstadt is the name of a street, not the old town as the name suggests. During World War I the street was centre of night-life and entertainment in Bruck.

Bohumil Vlček recalls a Czech waitress Růženka who worked in a certain tavern named u Růže (Zur Rose) and that many Czechs, including Jaroslav Hašek, visited regularly[a]. Further Jan Morávek, in an interview that was printed in Průboj 3 March 1968, adds that the author, before departure to the front was picked up by the patrol at U zlatého růže (Zur goldenen Rose). It is surely the same place, but there is great confusion about the real name of the place. Vlček also mentions that Jaroslav Hašek in the same situation was detained in a pub by the railway station. If this is the case, the hypothesis about Zum weißen Rössel is invalid as it was located about 10 minutes walk from the station. On the other hand Vlček explicitly states that the "Rose" was in Bruck, whatever colour or shape it might have appeared in. Josef Novotný also mentions the place in his memories from the war[b].

Bohumil Vlček

V lágru nás nic nepoutalo, proto po zaměstnáni navštěvovali jsme v Mostě hostinec u "Růže" kde nás obsluhovala naše česká číšnice Růženka / jak v románě též o tom zmínka :/ Tam byl stalým hostem Jaroslav Hašek, kterého jsem tam též osobni poznal. Většinou do restaurace chodili Češi, jednoročáci a i mužstvo od náhr. praporu.

Quote(s) from the novel

[II.5] Vymlouval se, že chtěl před odjezdem prohlédnout známý skleník hraběte Harracha u Brucku a na zpáteční cestě že zabloudil, a teprve ráno celý unavený že dorazil k „Bílé růži“. (Zatím spal s Růženkou od „Bílé růže“.)

Credit: Bohumil Vlček, Josef Novotný, Wolfgang Gruber, Friedrich Petzneck, Klara Köttner-Benigni, Jan Morávek

Also written:At the White RoseenU bílé růžeczFehér RózsahuDen kvite roseno

Literature

- Die „Abenteuer des Braven Soldaten Schwejk” in Österreich, ,1983

- Kde to bylo, ,6.4.1983

- Připomínky k románu "Dobrého vojáka Švejka", ,20.3.1956 [a]

- Z mých válečných pamětí, ,2021 [b]

| a | Připomínky k románu "Dobrého vojáka Švejka" | 20.3.1956 | |

| b | Z mých válečných pamětí | 2021 |

|

II. At the front |

| |

5. From Bruck on the Leitha toward Sokal | |||

| © 2008 - 2024 Jomar Hønsi | Last updated: 20.11.2024 |